Time Management Guidance for Tutors

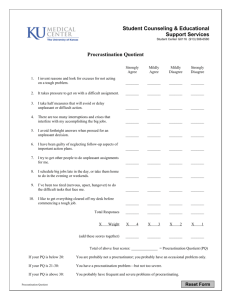

advertisement

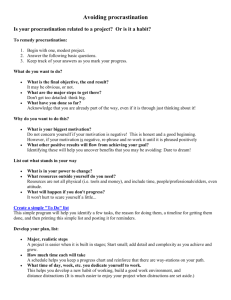

Guidance Notes for Tutors. Section 3: Time Management Introduction Managing time can be a difficult process for many HE students. A survey at the University of Reading, for example, found that 32 per cent of the students consulting the Study Advisers at the University of Reading initially came asking for support with time management (LearnHigher 2009). Students are expected to research and read a wide range of sources and to write a range of module assignments each semester. If they are in a hall of residence, they will need to look after themselves, and most need to find employment to supplement any loans or other financial assistance they receive. Not surprising then, that procrastination is an issue for many of them. Procrastination has been the subject of considerable research in recent years and it appears to affect a significant number of students. Self-reporting by students suggest that 80-95 per cent engage in procrastination of some sort (Ellis & Knaus, 1977; O'Brien, 2002), and almost 50 per cent procrastinate consistently, which leads to problems with assignments or other set tasks (Day, Mensink, & O'Sullivan, 2000; Haycock, 1993; Onwuegbuzie, 2000). A common form of procrastination in education is for the student to delay starting an assignment beyond the envisaged start point and then have to work furiously to finish it on time. However, other forms of time management concerns for students include perfectionism and poor planning. This Section of Trans:it aims, therefore, to help students consider their own attitudes and approaches to time management. There are four Units: 1 Unit 1: How well do you manage time? Unit 2: Time traps Unit 3: About time Unit 4: Four case studies Each unit offers enough material for a 50-60 minute taught session. These guidance notes include teaching tips from tutors who have successfully used the material featured in the Section. Unit 1: How well do you manage time? This unit starts with a self-assessment exercise of students’ perceptions of their strengths and weaknesses in relation to managing time. Some students may find it more difficult to identify their strengths than their weaknesses - and may need some help to get started with this. The exercise does give one example of a time management strength to get the students started, but they may need further encouragement. If so, additional examples are included in the list that follows. Strengths could include: Being punctual for college classes. Having understanding on the time it takes to complete set tasks. Good sense of time in relation to journeys, e.g. how long it might take to get from A to B. Self-discipline in getting out of bed at the time required by self or others. Sticking to any time agreed for going out or returning home. Being aware of the impact of unpunctuality on the lives of others. Not procrastinating at getting started on tasks they dislike. Letting others know if they are going to be delayed. Being time reliable with siblings. 2 Being time reliable with pet animals, e.g. exercising/feeding a dog when needed. Being time reliable with dependent others, e.g. older relatives. Effective at prioritising tasks. Not getting distracted or sidetracked from tasks. The time-management questionnaire that features in Unit 1 is widely used by undergraduate and post-graduate students at the School of Management, University of Bradford. One of its main uses is to identify individual elements of time and to encourage students to think about how effective they are in managing these. Teaching tip! Students can be encouraged to review their time-management strengths and weaknesses in the light of their questionnaire result. Unit 1 concludes by encouraging students to identify possible solutions to two of their most intractable time management issues. This encourages students and their peers to solve their own problems, rather than rely on their tutors to solve them for them. Teaching tip! This exercise is often more effective when done in a group, with students presenting their issues and the possible solutions to these, but then inviting their peers to contribute additional ideas. 3 Unit 2: Time Traps This unit looks at three big time traps for students: procrastination; perfectionism; and poor planning (Neville 2007). Each of these ‘time traps’ is described and presented with a short self-evaluation questionnaire and students asked to tick any which apply to them. They are also asked to think about possible solutions to two items self selected from each of the three traps. Teaching tip! As with the similar exercise in Unit 1, this exercise can be more effective when done in a group, with students presenting their issues and the possible solutions, but then inviting their peers to contribute additional ideas. Additional information for tutors: 1. Procrastination Procrastination is the deferment or avoidance, without good reason, of an intended or scheduled task until later. The word has its origins in latin: pro(forward) and crastinus (of tomorrow). Teaching tip! It can be useful to ask students for examples of when procrastination can be a positive thing to do. There are negative connotations attached to the word, but it is important to remember that not all deferment of action is bad. Sometimes deferment is the wise and positive choice: in the case of war, for example, or any other situation when the outcome of an action is unpredictable 4 and might even be harmful to others. It can also be seen as a useful personal ‘rebellion’ against the unquestioning acceptance of task upon task that may be given to us. It can be an opportunity to think about the range of tasks that we face – and whether they are all necessary, or need to be accomplished in the time frames set for us by others. Causes of procrastination The causes of procrastination are complex and as yet far from being fully understood. However, Steele (2007) examined several hundred academic studies of procrastination dating from the 1930s onwards in an attempt to identify the cause, effect and remedies for this trait or response. There appear to be five factors at work relating to: 1. Importance or value of set task to an individual 2. Desirability, or attractiveness, of the set task to individual 3. Confidence levels of person to successfully accomplish set task … and 4. Proneness of person to procrastination 5. Time available to do the set task These relate and connect with each other. Items 1-3, can be balanced against items 4 and 5. Items 1-3, if set on a ‘high’ priority scale setting, with 4-5 on ‘low’, will lead to reduced incidences of procrastination; whereas the converse situation is more likely to result in procrastination. 5 Proneness to procrastination Steele’s survey suggests that the following factors can impact on individual response to task procrastination: Aversion to the task Avoidance of an unpleasant, boring or difficult task for as long as possible Worry about failure Worry about failing; prefer to be viewed and judged by others as lacking in effort, rather than ability Rebellion Delaying starting tasks because of resentment about the task itself, or the person imposing it Poor time management Under-estimation of time needed to complete set tasks Depression or mood related Low energy/motivation levels, arising depression, or just ‘not in the mood’ responses to tasks Impulsiveness Procrastination Environmental factors Environmental factors, e.g. place of study, have an impact on motivation to start Easily swayed from one task to another; pursuit of immediate gratification or sensation. Enjoy working under pressure Relishing the ‘buzz’ of working close to the time limits 6 What is not clear is if chronic procrastinators are born or made. Joseph Ferrari believes that procrastination are generally made and moulded by family influence in one way or another. This might be by imitation of parental behaviour – or in rebellion of an over-controlling parent or parents who nag their children to do things to the parent’s agenda and timetable (Ferrari et al 1995). However, some commentators see a link between procrastination and anxiety traits (see Burka and Yuen, 1984), which can be the result of both inherited and nurture influences. It may be worth discussing these factors with students, to see to what extent they agree or identify with Steele’s analysis. Perfectionism Stoeber and Otto (2006) have identified two types of perfectionist, categorised as ‘perfectionistic strivings’ and ‘perfectionistic concerns’. Perfectionistic strivings are associated with positive aspects, and perfectionistic concerns with negative aspects. Healthy perfectionists rate high in perfectionistic strivings and low in perfectionistic concerns, whereas unhealthy perfectionists rate highly in both strivings and concerns (i.e. a flawed perfectionist). Working as hard and as well as one can in the time available is a healthy form of perfectionism. Sometimes an individual’s talents and interest in the task will lead them to exceptional results; other times the results are less spectacular. The flawed perfectionist will, however, beat themselves up emotionally for achieving less than perfect results. A less than perfect grade, for example, will cause them to fixate on a task and spend more time on it than is reasonable or necessary, whilst remaining oblivious to their own need to rest and keep their life in perspective. The following student comment summarises this paradox: 7 I’ve written and rewritten this essay, maybe five times, and I still don’t feel I can hand it in. The problem is that it has taken over my life. I’ve cut some lectures, left an important assignment for next week, which I know will cause even more problems, and I am spending all my time just endlessly trying to improve this essay. It’s crazy because I know it’s probably good enough, but I can’t help it… I so want it to be absolutely right.’ (University of Dundee Counselling Service 2003) The irony is, of course, that this fixation on a single assignment leads to time management going completely haywire and the flawed perfectionist is left to cope with a personal timetable now out of control, as other tasks stack up. The flawed perfectionist believes that only the best grades will give them peace and satisfaction. But it does not happen. Living life this way will deny them peace of mind - because demanding ‘perfection’ from self or others usually results in long term failure. What seems a perfect result at first rapidly becomes only ‘very good’ in their minds as they strive for something better, then better than better, and better still. Nothing is ever good enough. Being this type of perfectionist may also hinder their future chances of success in their professional lives, because they can become anxious ‘jobsworth’ types, worried about taking any new or creative actions that might produce an imperfect result, or draw criticism to them. The flawed perfectionist, if they get into a position of authority, can also make unreasonable demands on others, which can lead them into conflict with subordinates. 8 Tackling flawed perfectionism begins by saying ‘no’ to making unreasonably high demands of self or others; demands that produce only failure and frustration. It also means refusing to accept the unreasonable expectations of others. This is, of course, easier said than done, and it may be necessary for students with flawed perfectionist tendencies to seek support from the Counselling Service of an HE institution. A case study is included in Unit 4 of this Section to help students think about these issues in more depth. Poor Planning Poor forward planning is the third of the ‘time traps’ and the most common among students (and many non-students!). For students, it is often the result of inexperience of having to manage their lives: their time has often been monitored and managed for them by others. Now they have to do it for themselves - and it can be a shock. Sheila Cameron (2002, p.42) argues that there is a correlation between poor planning and a disorganized work area, and the first step toward improving forward planning is to organise one’s working area. A chaotic working area can add to a feeling that things are out of control. If a working area is in a mess- with papers, books everywhere – this can slow progress. The student has to hunt around for what they need, wasting time in the process. Having a neat working area has a positive psychological effect. It can speed work because, arguably, this makes the student feel more efficient and in control- and they will respond positively to this feeling - which may include more readily embracing the ideas presented in the next unit. 9 Unit 3: About Time This unit presents a range of time management tips that connect with: Taking a long term view Prioritisation of tasks Daily scheduling of tasks Avoiding distractions The Unit starts with a selection of time management ideas presented by students at a time management workshop at the University of Bradford. However, there are two blank spaces in the exercise and Trans:it students are invited to suggest two ideas of their own to the list. Teaching Tip! Ideas generated can be presented to others in the group, with a vote taken at the end of the session as to the ‘most useful’ suggestions made. The ‘Avoiding Distractions’ part of this unit presents the result of a survey at the University of Reading on the ‘top ten’ of student distractions (LearnHigher 2009). Trans:it students are encouraged to prepare their own ‘top ten’ distractions, then to compare it with the University of Reading list. Teaching Tip! Encourage students to contribute their own solutions to the Reading list of student comments. 10 Unit 4: Case Studies Case studies can be an effective way for students to address time management problems; it can be easier to give advice to others, but the process can also lead to some useful self-reflection on one’s own shortcomings. The case studies are drawn from the LearnHigher Centre of Excellence in Teaching and Learning (CETL) website, Time Management Learning Area; and from the University of Bradford, School of Management, Time Management workbook for students. Trans:it students can discuss these case studies among themselves and their own suggestions compared with the tutor suggestions presented on the LearnHigher website and in the University of Bradford workbook. The case studies 1. Dina Dina was a 2nd year Law student who was struggling to complete her assignment because she was unable to concentrate on reading. She tended to concentrate her reading into the afternoon, as most of her mornings were taken up with attending lectures. She described how she kept reading the same page over and over again without understanding or remembering what she’d just read, eventually giving up in despair. Dina described herself as someone who loved reading, who habitually read for pleasure and whose only real problems were on focusing on academic reading. She feared that this difficulty might be a symptom of her being “not clever enough” for her very competitive course. 11 LearnHigher presents the following advice: “The adviser explained to Dina that everyone has a good and bad time for focusing on difficult tasks and getting things done. For most people it is easiest to focus in the mornings and most difficult after lunch. Dina was using her most unfocused time of day to attempt the study tasks that needed most concentration. It was suggested that Dina should make herself a timetable, committing herself to studying at her best times (as many morning sessions as were available, plus late afternoons and early evenings when necessary). It was suggested that she ringfence time in the afternoons when she tended to lose focus for doing chores, answering emails, going to the gym etc. The adviser also explained how she might use the principles of active reading; that is, taking notes of key ideas” (LearnHigher 2009). 2. Leroy Leroy was in the final year of a Geography degree. Having thrown himself into university life with enthusiasm, he was now the Entertainment Editor of the weekly student newspaper and president of the Geography Society. These commitments took up a substantial amount of time, in addition to which Leroy was trying to complete a 12,000 word dissertation, two essays, and begin his revision for Finals. He felt completely overwhelmed and had got to the stage where he could not decide what to do first, and so was doing nothing. This was increasing his anxiety. 12 LearnHigher presents the following advice: “The adviser suggested that as a first step, Leroy should list everything he had to do, with the dates he had to do them by. Although Leroy was unenthusiastic (fearing that seeing it all written down would make him feel more stressed), he completed the list and was able to work with the adviser to decide on a few quick tasks to tackle straightaway to free up his study paralysis. Leroy also reluctantly agreed that he should relinquish at least one of his extra-curricula responsibilities to focus on study. That agreed, his larger study tasks (completing his dissertation, revising for Finals) were broken down into smaller steps to provide a series of achievable goals. Lastly, he was asked to mark up a realistic set of tasks he wanted to complete by the end of the week. Retuning two weeks later, Leroy agreed that although he found it difficult to give up some of the positions he'd worked hard to achieve, he did now feel more in control of his time. He said that, rather than seeing his tasks as an undefined mass that was impossible to untangle, he could now visualise them as a linear path to be followed to his goal - to complete his degree and get the good marks he deserved” (LearnHigher 2009). 13 3. Joe Joe has a tendency to build a task up in his mind into something bigger than it really is and beyond what is expected of him by his tutors. He becomes convinced he cannot deliver what he thinks is expected of him by the university in the time available. This reduces his confidence, increases his anxiety and leads to procrastination in starting assignments. The University of Bradford, School of Management, advice to Joe was, as follows: Joe should not fall into the trap of perfectionism. ‘Perfection’ as a concept and a life target is impossible to attain. It is a slippery eel of an ambition, as perfection will always elude us; a voice in our head will always say ‘do more, more, more’. It may be that others have pushed him too hard and too far in the past in this direction. He needs to aim at doing his best in a conscientious way. If he makes mistakes, so what? This is how we learn. He also needs to ‘deconstruct’ the assignment by re-phrasing the task into simple, manageable terms. With assignment questions, for example, he could try writing a mini-essay (50 words) that simply highlights the main point, or by explaining to another person his opinion on the subject. When you do this you reduce seemingly difficult tasks into something within your grasp. Even complex concepts have a core or key point, around which other ideas revolve. Get to the core, understand the core, and you start to control the written task. Joe could also break the assignment task down into easy manageable sub-tasks, and tackle each one of these separately. Often it is the apparent magnitude of the assignment task, combined with ‘perfectionism’ tendencies, which lead to procrastination. Dividing tasks up into bite-sized chunks can be the way out of this emotional impasse. (University of Bradford 2006). 14 4. Anita Anita is a part-time mature student in higher education and is finding it increasingly difficult to prioritise her time. She has a partner and two children in their teens, and is rapidly becoming overwhelmed with all the things required of her both at home and for the HE course. These include all the chores she feels she has to do for others in her household, plus the set reading and work for course assignments. The University of Bradford, School of Management, advice to Anita was, as follows: Anita could start by looking at the issue of the chores she feels she has to do at home. Are other people supporting her enough with her studies? If not, why not? Is the issue of perfectionism – about chores – one that she also needs to consider? 4-D Approach. Students in Anita’s position may have to adopt a ‘4 D’ approach to managing their time: De-commitment: identifying things that do not really need doing, and abandoning these; Deferment: putting things off till after exams or assignments have been completed; Downgrading: doing things to a less perfect standard; Delegation: negotiating with others to do things that you previously felt to be your responsibility. Anita could also start each day by listing in writing the things she has to do on that day, and into the near future. There is something very satisfying about having a list of things to do and ticking these off one by one when you do them! You start to feel more in control. However she needs to avoid starting with an unrealistically long list of things to do at the start of the day. (University of Bradford 2006). 15 References Burka, J. B., and L.M. Yuen (1983). Procrastination: Why you do it, what to do about it. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. Cameron, S. (2002). Business Student’s Handbook: learning skills for study and employment. 2nd edn. Harlow: Prentice Hall. Day, V., Mensink, D., and M. O'Sullivan (2000). Patterns of academic procrastination. Journal of College Reading and Learning, 30, 120-134. Ellis, A., and W.J. Knaus (1977). Overcoming procrastination. New York: Signet Books. Ferrari, J.R. et al (1995). Procrastination and Task Avoidance Theory, Research, and Treatment. New York: Plenum. Haycock, L. A. (1993). The cognitive mediation of procrastination: An investigation of the relationship between procrastination and self-efficacy beliefs (Doctoral dissertation, University of Minnesota, 1993). Dissertation Abstracts International, 54, 2261. LearnHigher (2009). Time Management Learning Area: resources for staff. Available at www.learnhigher.ac.uk [Accessed 29 Dec. 2009]. Neville, C. (2007). Procrastination [Workbook]. University of Bradford, School of Management Effective Learning Service. Available at http://www.brad.ac.uk/acad/management/external/els/pdf/procrastination.pdf [Accessed 2 Jan 2010]. O'Brien, W. K. (2002). Applying the transtheoretical model to academic procrastination. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Houston. Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2000). Academic procrastinators and perfectionistic tendencies among graduate students. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality,15, 103-109. Steele, P. (2007). The Nature of Procrastination: A Meta-Analytic and Theoretical Review of Quintessential Self-Regulatory Failure. Psychological Bulletin Vol. 133(1), Jan. 2007, pp. 65-94. University of Bradford (2006). Time Management. School of Management Effective Learning Service. Available at http://www.brad.ac.uk/acad/management/external/els/pdf/timemanagement.pdf [Accessed 2 Jan 2010]. 16 University of Dundee Counselling Service (2003). Perfectionism. Available at http://www.dundee.ac.uk/studentservices/counselling/leaflets/perfect.htm [Accessed 2 Jan 2010]. Stoeber, J. and K. Otto (2006), ‘Positive conceptions of perfectionism: Approaches, evidence, challenges’, Personality and Social Psychology Review , 10 (4): 295–319. 17