Fry Collectors livelihoods - Bangladesh Shrimp and Fish Foundation

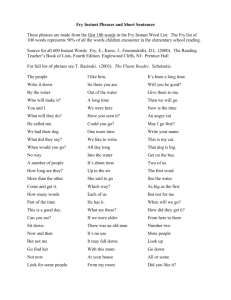

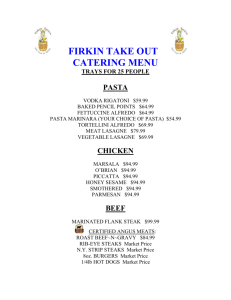

advertisement