2004 AP English Language and Composition FRQ

advertisement

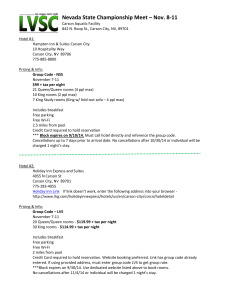

Note: I have helped walk my students through an AP prompt (Rachel Carson, 2004 Form B, Question 1). The following shows the activities and Directed Reading and Teaching Activity that I have done with my students (in addition to giving them the official prompt from AP Central). I also have shown them my response, trying to show that someone can write a well-reasoned response without having to use the difficult AP terms (like zeugma and epizeuxis, for example). AP Prompt, Carson (DRTA) Frontloading/Anticipation Activity: Journal. Look at the following list of words: “habit of killing,” “merits of killing,” “mission of death,” “casualty list,” “doomed,” “escaped death,” “lethal film,” “needless war,” “chains of poisoning,” “everwidening wave of death,” “unselective bludgeon,” “sterile world,” “authoritarian temporarily entrusted with power,” “a moment of inattention by millions” Write ideas/images/stories that come to mind based on these words. Then brainstorm what a short article that includes these words might be about. Purpose: Learn some of the “rules of notice” for reading AP prompts (and other materials). Discuss/notice the importance of diction, and how word choice creates/affects an argument. Think about the importance of “negative space” and bringing up things that are not counted or can’t be seen. Think about opposing views and how an author may exaggerate or mis-characterize her opposition. Notice audience and purpose in this particular speech, and gain ideas on how to read for such in the future. Feel well-prepared with ideas to respond to this AP prompt. Activities: Journal & discussion Brief discussion of what “rules of notice” are Directed (and individual) reading of Carson’s AP excerpt and my guides Role-playing Discussion of DRTA and role-playing & discussion of how changed students’ reading Discussion of notes/outline for AP prompts Students create notes/outlines Write response (in class or as homework) to the prompt 2004 AP English Language and Composition FRQ Suggested time—40 minutes. In 1962, the noted biologist Rachel Carson published Silent Spring, a book that helped to transform American attitudes toward the environment. Carefully read the following passage from Silent Spring. Then write an essay in which you define the central argument of the passage and analyze the rhetorical strategies that Carson uses to construct her argument. A.P.= “answer the prompt.” Often the prompt has 2 parts, as is the case here (“central argument” and “rhetorical strategies”). Think carefully about the prompt’s hints/words. “Argument” suggests Carson is arguing/trying to convince someone of something, likely trying to motivate someone to do something. Whenever you see “Argument,” you might also plan to look for ethos, pathos, and logos (among other options). Word choice is often also key. “Central” means key/main point and it also suggests it’s a point that comes up several times. “Rhetorical strategies” refer to techniques in writing to move an audience, such as our vocab. terms, aspects of SOAPSTONE, etc. (for example: diction, organization, evidence, repetition, pathos, ethos, etc.). “Analyze” is also part of the prompt, and it suggests the AP readers want you to break down Carson’s speech and point to particular things she does and the patterns they create. Notice the title of Carson’s book. Titles are “rules of notice.” As the habit of killing grows—the resort to “eradicating” any creature that may annoy or inconvenience us—birds are more and more finding themselves a direct target of poisons rather than incidental one. There is a growing trend toward aerial applications of such deadly poisons as parathion to “control” concentrations of birds distasteful to farmers. The Fish and Wildlife Service has found it necessary to express serious concern over this trend, pointing out that “parathion treated areas constitute a potential hazard to humans, domestic animals, and wildlife.” In southern Indiana, for example, a group of farmers went together in the summer of 1959 to engage a spray plane to treat an area of river bottomland with parathion. The area was a favored roosting site for thousands of blackbirds that were feeding in nearby cornfields. The problem could have been solved easily by a slight change in agricultural practice—a shift to a variety of corn with deep-set ears not accessible to the bird—but the farmers had been persuaded of the merits of killing by poison and so they sent in the planes on their mission of death. The results probably gratified the farmers, for the casualty list included some 65,000 red-winged blackbirds and starlings. What other wildlife deaths may have gone unnoticed and unrecorded is not known. Starting sentences are usually important and are a “rule of notice.” Note in particular Carson’s word choice (I’ve added the italics). Would the farmers who used the pesticide agree with her word choice? How does her word choice influence your response on this issue? What is she implying with her word choice, or what arguments are understood if you accept her word choice? Notice the underlined words (I’ve added the underlining). How do these words/phrases provide ethos (credibility) to Carson? Note the quote. Authors are very careful about what they choose to quote, usually paraphrasing is good enough. If they quote, it’s usually a strong phrase or they think it will bolster their argument by having their source give the actual words. Notice the bolded words (I added.). What might she not be telling us? How do you think the farmers would respond to her characterization of their choice/actions? Why does she introduce something unknown/not Parathion is not a specific for blackbirds: it is a universal killer. But such rabbits or raccoons or opossums as may have roamed those bottomlands and perhaps never visited the farmers’ cornfields were doomed by a judge and jury who neither knew of their existence nor cared. And what of human beings? In California orchards sprayed with this same parathion, workers handling foliage that had been treated a month [italics are Carson’s] earlier collapsed and went into shock, and escaped death only through skilled medical attention. Does Indiana still raise any boys who roam through woods or fields and might even explore the margins of a river? If so, who guarded the poisoned area to keep out any who might wander in, in misguided search for unspoiled nature? Who kept vigilant watch to tell the innocent stroller that the fields he was about to enter were deadly— all their vegetation coated with a lethal film? Yet at so fearful a risk the farmers, with none to hinder them, waged their needless war on blackbirds. recorded? (The unexpected—such as telling us something that didn’t occur—is a “rule of notice.”) What does the “or” (polysyndeton) add? Why did she choose these animals, as compared to snakes, rats, skunks, crocodiles, etc.? Continue to notice word choice, such as “casualty list,” “roamed,” “doomed,” etc. Why telling us what did not happen? What is another way of telling what did occur? Or what facts are here? Why would she choose “roam” again after using it also in the last paragraph? How does she characterize these boys (who are likely trespassing)? What words does she use to characterize them and their search? Why so many questions in a row? What emotion does she want us to feel? And what might her aim be? (When the syntax really changes—such as with a list of questions—this is a “rule of notice.”) Often, speeches are supposed to motivate, and the end reveals the plan/goal. What seems to be Carson’s point at the end of this paragraph? Who do you think her primary audience is, and what is it she wants them to do? How would the farmers react to her word choice/characterization (such as “needless war”)? In each of these situations, one turns away to ponder the question: Who has made the decision that sets in motion these chains of poisoning, this ever-widening wave of death that spreads out, like ripples when a pebble is dropped into a still pond? Who has placed in one pan of the scales the leaves that might have been eaten by the beetles and in the other the pitiful heaps of many-hued feathers, the lifeless remains of the birds that fell before the unselective bludgeon of insecticidal poisons? Who has decided—who has the right [italics are Carson’s] to decide—for the countless legions of people who were not consulted that the supreme value is a world without insects, even though it be also a sterile world ungraced by the curving wing of a bird in flight? The decision is that of the authoritarian temporarily entrusted with power; he has made it during a moment of inattention by millions to whom beauty and the ordered world of nature still have a meaning that is deep and imperative. Images are often important (and can be a “rule of notice”). What does her image suggest? What word choices are important here? Notice how she characterizes/makes us imagine the birds. Notice the many words that deal with death, war, terror that she uses. (If you notice a theme/pattern with word choice, this is an important “rule of notice.”) Notice the repetition of “who” and “decide.” Often repeated words are important (and are a “rule of notice”). She suggests the farmers want a world without insects and a sterile world. Is that a fair characterization? Notice also the poetic wording for the bird imagery. How might the farmers describe these birds that are likely eating their crops? The ending is a “rule of notice” and is often the moment for the “call to action.” What seems to be Carson’s main interest or call to action? Who is her primary audience she hopes to reach? How does she help characterize them/create them? (If the ending helps you to figure out her audience, you may want to skim over her excerpt again with this audience/call in mind.) After reading the passage, get into groups of 4. Have two people play farmers and two people play Rachel Carson. What will the farmers take issue with? What wording and arguments from her excerpt will they want to point out? What arguments will they have? Create a discussion, based on this excerpt and your own common sense and imagination, as to how this conversation would likely play out. Now, whoever acted as the farmers will act as Carson(s). This time, the earlier Carson characters will be apathetic people and/or busy city people who are not necessarily pro-environment. Carson needs to try and convince them to care about this issue, and the apathetic/busy people will respond in whatever way you feel is appropriate. After going through the role plays, we will discuss as a class. Afterwards, return to the prompt and do some notes/outlining to prepare to write for this AP passage. Also, think about what stood out to you through my hints or through the role plays that you might have overlooked if you had read it on your own. I’ll give you time to share or write thoughts on this question. After students have had the chance to brainstorm, outline, and write their response, I have shared my response with them, which follows. Example response to Carson’s AP prompt. I wrote this in the allotted 40 minutes. A student asked me if it was necessary to use all the fancy terms (such as polysyndeton, juxtaposition, and diction) to respond to the AP questions. I tried to show that as long as one’s thought process was clear and evidence insightful and strong, one could still write a strong analysis without using the fancy terms. —Shauna McPherson, Lone Peak HS AP Language teacher Rachel Carson’s world is black and white. The farmers’ actions cause them to be the enemy; nature and all on her side are the good guys. The incident is not a grey one, not a complex one, from Carson’s view. And it is imperative and urgent that laypersons—lovers of nature—right this wrong and take on the enemy: the pesticide-utilizing farmer. Carson’s portrait of the incident, the farmers, and her audience aids in her appeal. (Her diction and pathos, in particular, move her audience to agree with her.) Carson’s passage, from her book Silent Springs, argues against farmers’ use of pesticides— particularly aerial pesticides, such as parathion. She argues that such pesticides are unnecessary and extremely dangerous. They not only eliminate the pest in question (reason alone for Carson to decry them), but they can harm or kill other animal-life, wildlife, and humans. Carson utilizes a quote from The Fish and Wildlife Service to back up her claim. In addition, her naming of the actual pesticide, her information about an incident of its use in Indiana, and her use of statistics with the avian deaths all contribute to her credibility. She appears knowledgeable about the situation, the animals, and their habitats. In explaining the problem, Rachel Carson appeals to her audience with strong word choice and emotion. She characterizes the farmers who use pesticides as heartless killers. She refers to their actions to eliminate the birds that attack their crops with emotionally-charged language: “the merits of killing,” “mission of death,” “a universal killer,” “escaped death,” “lethal film,” “wave of death,” “doomed,” and “bludgeon.” Obviously, she guides her audience to feel fear and distaste for those who would harm “unspoiled nature,” the land where cute animals (“rabbits or raccoons or opossums”) frolic and “roam.” Carson blames the farmers not just for the deaths that occurred, but those that might have occurred, and those that nearly occurred. Additionally, Carson can see no reason why such killing could be warranted; she offers no concessions to her opponents’ view and adds evidence that the issue “could have been solved easily” (emphasis added) through a change in which variety of corn was grown. From the farmers’ views, perhaps there is a valid reason why such an agricultural change was not feasible or desired, but Carson does not provide such information, or anything for that matter that might shift her portrayal from the black-and-white to the grey. Indeed, she portrays the farmers as killing thousands of birds simply because they were “annoy[ed]” and “inconvenience[d].” In fact, she says, they were likely “gratified” with the results of the large “casualty list.” (If they were gratified, it was to have the crops free from harm, but Carson’s phrasing makes the farmers sound gleeful with the death of the birds.) They likewise likely did not care about any other animals killed as a side-effect of the pesticide, according to Carson. (Most farmers are likely in the profession because they have a healthy respect—or even joy—in the outdoors, in working with animals and nature. But, Carson wouldn’t mind if we forgot that. In her view, the farmers are an unfeeling and inhumane group, united in their violence against nature, the defenseless, and the common man.) The farmers and their desire for a “sterile,” lifeless world are contrasted with the meaningful, joyous world of nature. In Carson’s argument, nature and the audience are both the good guys. Nature is portrayed as a place where cuddly critters “roam.” When she portrays animals that may have died (for which she can offer no statistics), she does not choose snakes, skunks, and rats, but rabbits, raccoons, and opossums. Her phrasing of the animals, additionally, focuses the audience on each one: they are not presented as a group (such as “rabbits, raccoons, and opossums”) but as individuals: “rabbits or raccoons or opossums” so that the emotional appeal and loss is felt with each “or.” Additionally, Carson connects these roaming, collateral-damage animals with boys who might “roam through woods or fields” or “explore the margins of a river.” If her word choice of “roam” and “explore” were not enough to paint an idyllic, Huck-Finn like existence, she brings the point home by calling such wanderings a “search for unspoiled nature.” Unspoiled nature can be the home of destruction, death, and terror (earthquakes, fire, tsunami, hurricanes, deadly plants and insects, wild predators, etc.), but Carson wants no connotations with nature that might taint it and cause her listeners to think of the need to tame it. Instead, her nature—and those who love it—is a place where “the curving wing of a bird in flight” graces our existence. Carson looks for—and creates—an audience who values nature. In addition, she appeals to the common individual’s desire to fight the machine, the system (in Jack Black’s words: “the man”). Basically, she appeals to her audience’s desire to make a difference in the world. She sets up her case as urgent, and shows that—without our intervention—such death will continue and perhaps even spread like ripples, in a “wave of death1.” She argues that the farmers create a “needless” hazard to all because they have “none to hinder them” (emphasis added). They are authoritarians who have mistakenly been entrusted with a power that they have abused due to “the inattention” of millions. Clearly, Carson wants her audience to feel an urgent sense to act. Such action will show that they are indeed not “inattentive” but instead the force that stops tyranny. And the force for whom “beauty and the ordered world of nature still have a meaning that is deep and imperative.” Carson’s final word in this essay (“imperative”) not only shows the power nature holds in her life—and the life of her imagined audience; it also subtly underscores her audience’s imperative to act; to save our springs2 from turning silent. Her “wave of death” idea suggests a slippery slope fallacy. She does not merely contend against the use of parathion but argues that it can lead to much larger and greater events. And if we halt this problem, we have stopped even greater, unimaginable forms of tyranny. 1 Carson’s title powerfully empowers nature. A spring of water is a force of life, a place for renewal. The season of spring is symbolically a time of rebirth and life. With such connotations, how can one allow such a spring to become silent? 2