CHAPTER II. Stereotype and literary images in Modern English

advertisement

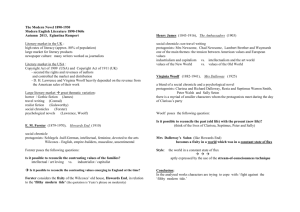

"Comparison of stereotyped women`s roles in Modern English Literature" CONTENT: INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 2 CHAPTER I WOMEN'S ROLE IN MODERN LITERATURE ....................... 5 1.1. Heroine as a central component in modernists novels .............................. 7 1.2 Literary interpretation of women's role in society ................................... 10 CHAPTER II. Stereotype and literary images in Modern English Literature .. 14 2.1. Virginia Woolf heroines and their stereotypes ........................................ 14 2.2. Thomas Hardy heroines and their stereotypes ........................................ 18 CONCLUSION.................................................................................................. 26 REFERENCES .................................................................................................. 29 1 INTRODUCTION Gender issues have been a topic in written literature since ancient times, when Greek poets such as Sappho and Homer wrote of female sexuality, marriage, and emotional bonds between women and their families, and philosophers questioned, and usually denigrated, the role of women in society. Christianity broughat to literature the dichotomous virgin-whore—or "good girlbad girl"—archetype, modeled after the seemingly contradictory figures of the Virgin Mary and the Biblical prostitute Mary Magdalene, which has survived to the present day in literature and popular culture. In the Victorian period female literary paradigms began to shift as more women openly published their writings and women's emancipation became a major societal issue. At one end of the spectrum was the Victorian "Angel of the House," which placed women in the position of helpmate, homemaker, and superior social conscience, but which ultimately limited women's options to the realm of home and occasional volunteer work. At the other end was the newly emerging liberated woman who candidly demanded her right to education, suffrage, and the single life but who was generally treated as an outcast by respectable society and still could not vote, inherit property, or easily cultivate a career. Both figures appeared in and were scrutinized by the literature of the time. In the early twentieth century, as the psychoanalytic theories of Sigmund Freud became widely read, literature by and about women took on an interiorized dimension. Many later feminist thinkers considered Freud's ideas about women misogynistic and claimed that they said more about Freud's own insecurities and neuroses than about the actual state of women's psyches, but it cannot be denied that concepts such as castration anxiety, penis envy, and Oedipal and Electra complexes strongly influenced Western notions about women, particularly in literature, throughout the twentieth century. Literature by and 2 about women in Latin American, Caribbean, Asian, and African countries has tended to focus on many of the same issues, in addition to more fundamental questions of human rights and the effects of colonization and slavery on women. In the modern feminist era—particularly after women earned the right to vote in many Western countries and gained greater access to education and the workplace—literature has concentrated increasingly on women's changing roles and continued obstacles to equality. Although it is difficult to think of this being the case now, novels were once the province of the upper classes, for that thin segment of society that could read and not for the teeming masses stopping by the airport bookstore. Thus even when the world depicted in the novel was not that of the world of the upper classes, the readership was an elite one, and novels were thus written for them. Thus many of the changes that we see occur as we shift from the decidedly non-modern form of the chivalric romance to pre-modern form of the picaresque to the entirely modern styles of Romanticism and Realism are reflective of changes in the nature of reading and the reading public. Other important changes reflect changes in the conception of love, in the place that love held in society in general and in the biography of each person's life, and in attitudes about fate and destiny. The subject of the research work is the analysis of women`s roles in Modern English Literature. The object of the given course paper is women`s roles in Modern English Literature. The aim of the research work is to analyze women`s roles in Modern English Literature. The tasks of the research work are: to analyze women's role in modern literature; to compare Virginia Woolf's heroines and their stereotypes with heroines of Thomas Hardy; 3 to single out the pecularities of heroines and their stereotypes; The given course paper consists of the introductory part where the subject, the object and the aims of the paper are revealed; two main parts, conclusion and lisl of references. 4 CHAPTER I WOMEN'S ROLE IN MODERN LITERATURE Women in classical literature are seen primarily through the eyes of men. Social mores prevented most women from publishing their own writing, so their views had a very limited audience. From the classical Greek plays to Chaucer's Canterbury tales to Shakespeare's plays, we find extreme types of female characters, nearly all stereotypes. Men tend to be individuals with quirks and flaws, some evil with a touch of goodness and others good with a touch of evil. Women tend to be one-sided and flat. The Greek classics portrayed Klytemnestra and her lover drowning her husband in the bath, and they showed us Elektra selflessly taking revenge for her father's murder, even though it means certain death for her. Helen of Troy, contrary to popular misconception, is portrayed as a selfish, spoiled brat, in contrast to Andromache, the faithful wife of Paris' brother Hector. The women represent either total evil or saintliness, with no middle ground. [39] In the 1200s we find Chaucer's bawdy, sinful Wife of Bath, and then we read his portrayal of the pure and holy Saint Cecilia. To be fair, it must be pointed out that his male characters also tend to be stereotypes, from the evil Pardoner to the cuckolded husband and the courtly lover. At about the same time, Boccaccio's Decameron presents many of the same characters, with slightly different names, in the same situations in similar places. In Shakespeare, we find the murderous Lady Macbeth and the intelligent, kind-hearted Portia (although she does legally destroy Shylock in A Merchant of Venice). We have the innocent lovers in comedies such as All's Well That Ends Well, and we have weak, sinful women such as Hamlet's mother. Interestingly, female characters in Shakespeare's plays were portrayed by boys and young men because it was considered unseemly for women to act on the stage. In fact, acting as a woman's profession was considered as low as 5 prostitution. Men dominated literature until the Romantic Revolution of the 1800s, when women such as William Wordsworth's sister Dorothy began to publish poetry and journals. However, novels and plays were still considered the rightful domain of men. Women who did publish their writing nearly always used masculine pseudonyms. For example, the Bronte sisters published Wuthering Heights, Jane Eyre and other novels under male names. Mary Shelley published Frankenstein anonymously, leading the literary circles of the early 1800s guessing who had written that masterpiece. Finally, Jane Austen published Pride and Prejudice and other classical novels under her own name, even though that act limited her readership. Men simply did not read "women's literature". It was considered inferior to men's literature. Even her work tends to show stereotypes. The major goal of most of her female characters is to marry well. They tend to be stereotypes, such as the strong-willed young woman, the silly mother of four girls, the tramp and the respectable lady. Louisa May Alcott portrays more fully developed female characters in her classic novels Little Women and Little Men. Jo, Beth, Amy and Meg are individuals that you would recognize if you met them on the street. Living in what is often called a post-feminist age, those of us who still identify ourselves as feminists have learned that women's progress cannot be plotted on the kind of clean upward trajectory of increasing opportunity and power that meliorist narratives have often attempted to construct. Advances are often followed (and even accompanied) by setbacks, gains in some areas of experience offset by losses in others. Women still have to run very hard just to stay in place--or even to keep from losing too much ground. Feminist historians are still debating the answer to Joan Kelly's famous question, "Did Women Have a Renaissance," but the answer increasingly seems to be "No." During the course of the seventeenth century, English women lost 6 ground in a number of fields. Excluded from many trades in which their predecessors had been active, they were also confined by the rising barriers that defined the household as a private world, separate from the public arenas of economic and political action. Or so it has seemed to many feminist scholars. Mary Beth Rose complicates the picture by arguing that the feminization of the household can be seen in many ways as an advance for women, since this was a period when the private world itself acquired increased prestige and importance in the cultural imagination. Within this context, she believes, heroism itself was regendered from masculine to feminine, as passive suffering and endurance-virtues traditionally regarded as appropriate to women--came to replace warlike action in the public sphere as the proof of heroic status. The stakes in this argument are high because, as Rose points out, conceptions of heroism reveal the fundamental ways a culture assigns value.[38] Women have evolved as both characters and writers in modern literature, compared to their limited characters and roles in classical literature. Reader and writers have matured, and the characters of both men and women have become more fully human. Women in particular are portrayed as rounder, more fully human people. 1.1. Heroine as a central component in modernists novels In several lectures she gave during the 1930s and later, writer Virginia Woolf reflected upon the challenge she and her fellow female artists faced at the beginning of the century—Woolf noted that although women had been writing for centuries, the subjects they had written about and even the style in which they wrote was often dictated not by their own creative vision, but by standards imposed uponwomen by society in general. Advances in women's issues, such as the right to vote, the fight for reproductive rights, and the 7 opportunities women gained during the first half of the century in the arena of work outside the home were major developments. Despite these changes, women artists during these years continued to feel restricted by imposed standards of creativity. It would take, notes Elaine Showalter in numerous essays detailing the growth and development of women's writing in the twentieth century, several decades before women would completely break the mold of respectability under which they felt compelled to write. Fuelled by the feminist movement of the early twentieth century, many women authors began to explore new modes of expression, focusing increasingly on issues that were central to their existence as women and as artists. [35] By the end of the 1950s and the beginning of the 1960s, with the rise of the second wave feminist movement, women artists began expanding their repertoire of creative expression to openly include, and even celebrate their power and experiences as women. Works such as Betty Friedan's The Feminine Mystique (1963), Sylvia Plath's The Bell Jar (1971), and others by authors like Germaine Greer, Gloria Steinem, and Marilyn French all helped to awaken the feminine consciousness, paving the way for later writers to explore the reality of women's experience in their writings openly and freely. Works of literature by women authors during the 1960s and later thus began to focus increasingly on women's viewpoints, with issues such as race and gender, sexuality, and personal freedom taking center stage. Additionally, these years also witnessed the emergence of feminist literary theorists, many of whom set about redefining the canon, arguing for inclusion of women writers who had been marginalized by mainstream academia in the past. The latter half of the twentieth century also provided fertile ground for growing recognition of women writers of color. Lesbian literature has also flourished, and women have openly explored concerns about sexuality, sexual orientation, politics, and other gender issues in their works. [2] Prior to the mid-1960s, women writers who ventured beyond the 8 established feminine stereotypes were regularly characterized as "outcasts," denounced as vulgar or, in the case of Simone de Beauvoir, even "frigid." Nonetheless, many of them persisted in exploring new ways of expression, and poets such as Adrienne Rich, Audre Lorde, and others continued to write works articulating the struggle they faced as authors who could choose to "write badly and be patronized or to write well and be attacked," according to Show-alter. Another aspect of this struggle to gain respect as independent artists was the fight between women who felt compelled to "transcend" their femininity, opting to write as androgynous artists—Woolf chief among them—and others, including Erica Jong, who felt strongly that unless women could find the means to express themselves openly and clearly, they might as well not write at all. Eventually, many women writers in the 1960s and later broke through the stereotypical and restrictive paradigm of female authorship, creating and publishing works that abounded in an open celebration and exploration of issues that were central to women's existence, including sexuality. By the 1990s, critical and academic opinion had shifted, and works such as Eve Ensler's The Vagina Monologues, which deals directly with women's physical and emotional experiences, were hailed as both innovative and literary. A similar, yet different path to progress marks the writing of women authors of color, who eventually gained critical recognition for their efforts as chroniclers of their cultures, races, and gender. Although there were numerous black female authors writing during the early part of the century, especially during the heyday of the Harlem Renaissance, black feminist authors's exploration of both race and gender issues in their writing kept them outside the American feminist discourse that was dominated by either black male activists or white feminists. Scholars have also pointed to the fact that while works such as Friedan's The Feminine Mystique did much to draw attention to the emerging feminine consciousness, they did not address the needs and issues significant to women of color. Further, the narrative strategies used by such 9 pioneering black authors such as Zora Neale Hurston, whose works focused primarily on the private and domestic domain, were, until the 1970s and 1980s, dismissed by both white feminists and black male intellectuals because of the perception that their focus was too limited and narrow. Later critical opinion, however, has reevaluated the writing style and strategies used by many female authors of color to recognize that the personal narrative is a powerful and uniquely expressive mode of extrapolating and commenting upon the state of the world inhabited by these writers. Asian writers have used these strategies particularly well to counter stereotyped images of their own culture and gender. In several anthologies published in the late-twentieth century, including Asian writers, both male and female have attempted to create new images of Asian American literature. Asian women writers have been faulted for creating what are perceived as unrealistic portrayals of Asian American culture, especially images of the Asian woman as powerful and dominant, often seen in the works of such writers as Maxine Hong Kingston and Amy Tan. Mitsuye Yamada has addressed this conflict in her writing, arguing for a cohesive creative vision and the space to express it. Modern women's writing continues to explore new genres and means of expression, and women writers today participate fully in both the creative and scholarly process. Women's studies, feminist literary theory, and women's mode of writing and expressing are now established areas of academic environments, and women are exacting continued and growing control over their own literary and social spheres. 1.2 Literary interpretation of women's role in society The early decades of the twentieth century were filled with dramatic turmoil and change within United States and abroad, all of which impacted the 10 nascent feminist movement. Two world wars, rapid industrialization, urbanization, and a depression placed enormous stress on traditional social structures and domestic relationships, from the workplace to the family. In fact, more women entered the professional workforce during the first two decades of the century than at any other time in history. Though American women were granted suffrage in 1920, these were difficult times for the feminist movement. The issue of suffrage had united many women around a common cause, but once women gained the right to vote, the movement suffered from conflict and lack of formal organization. The militant nature of many suffragists also caused the movement to lose momentum in mainstream society, and for many years feminists were viewed as an extremist minority. Despite the success of the suffrage movement and the great influx of women into the workplace before and during World War II, a resurgence of traditional attitudes concerning the home and family would come to define the postwar period. As many feminists argue, the wars served to both empower and suppress women, whose newfound freedom and independence during the world wars was almost immediately ceded to a newly reestablished sense of patriarchy. Women who had supported the war effort through their labor returned home and were once again relegated to domestic duties and secondary status. Such restricted gender roles, exemplified by the conformity and traditionalism of the 1950s, continued to limit the opportunities and experiences of women until the rebirth of the feminist movement during the late 1960s and 1970s. Amid such conflicts and evolving gender roles, the first half of the twentieth century witnessed a flourishing in the literary arts and the development of new media such as radio, film, and, by the late 1940s, television. American drama in particular reached a high point in the 1920s, with dramatists Eugene O'Neill, Elmer Rice, and Maxwell Anderson writing many 11 of their best works during this decade. Meanwhile, poets such as Amy Lowell, H. D., and Sara Teasdale elaborated upon the prewar modernism pioneered by T. S. Eliot, W. B. Yeats, Wallace Stevens, and Ezra Pound. By the late 1950s, however, celebrated poets such as Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton would lead a turn away from formal detachment toward a more emotion-laden subjectivity in confessionalism. During the first half of the twentieth century many male and female authors also turned to the novel to sketch and satirize the materialism and anomie of the modern condition. Important novelists of the period include Theodore Dreiser, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Ernest Hemingway, along with wellknown female novelists Edith Wharton, Katherine Anne Porter, and Gertrude Stein, whose experimentalism defied classification. A growing number of women writers from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds also emerged during this time. Drawing upon their varied experiences as Asians, Africans, and Native Americans, many of these female writers addressed issues of gender and ethnic identity from new and compelling perspectives. Together, such women provided insight into the lives of women in general and the often denigrated minority populations of which they were a part. In particular, African-American writers came to prominence as part of the literary and artistic movement known as the Harlem Renaissance, which eached its peak during the 1920s and 1930s. This movement provided opportunities for many African-American women writers, including Zora Neale Hurston, Nella Larsen, and Jessie Redmon Fauset, to address issues of race and gender in their works. Such writers also gained appreciation for their declaration of cultural independence and their contribution to the development of an indigenous American language and literature. While women writers and artists participated in the thriving arts and literary movements during these years, many of them struggled deeply as creators. The world wars had a profound effect on the generation of writers that witnessed them, particularly women who bore the brunt of the social and 12 cultural changes that resulted from these conflicts. Caught between their own aspirations as writers and artists, but confronted with a reality that provided little in terms of equal opportunity or rights, many female authors felt frustrated during these years. In addition, female literary achievement was largely downplayed in academic institutions due to the negative backlash against the suffragists and, more broadly, because of a patronizing and dismissive view of female intellectuals among male cultural elites. Contemporary critic Elaine Showalter has drawn attention to the conflict, repression, and even decline suffered by many women writers during the early twentieth century. According to Showalter and other scholars, the years following the end of World War I were difficult for female novelists and poets in particular, who were regarded as writers of little substance. Yearning to write about serious issues facing their times but pushed to the periphery, poets such as Teasdale, H. D., Lowell, and Edna St. Vincent Millay were unable to find suitable literary models in past female poets. Additionally, the notion of poetry as an art form that transcends personal and emotional experience, a view expounded by male poets such as Eliot and Pound, led many female poets to feel that their work was being marginalized. Faced with stiff reaction against the type of personal and lyrical poetry many of them wanted to write, Millay and others found it increasingly difficult to continue writing. Some female writers curtailed their creative work and turned their energies to political causes instead, using alternate means such as journalism and reporting to express their opinions. Some writers found ways to incorporate political activism in their fiction and established a model for women writers of the 1960s and beyond. 13 CHAPTER II. Stereotype and literary images in Modern English Literature 2.1. Virginia Woolf heroines and their stereotypes Virginia Woolf, due to her special existence and her unique character as a woman writer, struggled between life and death all her life. On the one hand, she could not get rid of the idea of death; on the other hand, she struggled against the idea persistently. To live or to die, the contemplation became the major motif of her novels. Mrs. Dalloway is one of Woolf’s most loved and most written about novels, in which there is such a looming spirit perpetually dancing between life and death, bringing to the readers with a closer, candid look into the personalities and idiosyncrasies of each person as well as the ultimate meaning of existence which Woolf herself tried to explore through her writings. Virginia Woolf, being granted as not only one of the eminent modernists but also a significant articulator of feminism, is extremely admired by her unsurpassed oeuvre and her concept of women’s situation. Marilyn Schwinn Smith discloses that Betty Friedan’s claim corresponds to Woolf’s—women need physical and spiritual liberation. Both the activist’s (Friedan’s) and the artist’s (Woolf’s) concerns for women are embedded in Michael Cunningham’s The Hours, a rewriting of Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway. Notwithstanding the commentaries on The Hours are controversial, Birgit Spengler approves Cunningham’s manipulation of his characters as the development of Woolf’s. The critic further demonstrates the discrepancy in the two texts, including Cunningham’s closing the gap between high art and popular art and his quandary of being restricted by the conventional writing strategies. This advocacy of female multiplicity reflects on both Woolf’s characters 14 and her writing style – mobile plural viewpoints, which is harshly denounced by Elaine Showalter’s strong accusation of Woolf’s undermining the unified self [25, p. 311]. Nevertheless, Toril Moi singles out that the nucleus of Showalter’s critique of Woolf is actually a “phallic self,” the unified solid One contrasting with his residuary Other[18, p.8]. Possessing the features of multiplicity and diversity, women seldom have the equal status to men. They rarely have the chance to wield their talents in the public field because they are basically excluded from it. Women’s prohibition from citizenship and the ellipsis of female values are explicitly displayed in Linden Peach’s critique of Mrs. Dalloway’s infantilization and her indifference to politics. Clarissa’s allowance of her being “infantilised” under her husband’s care exposes her contemporary women’s plight of being subjugated to men[19, p.105]. The compulsory infantilization unveils a hegemony of the male-dominated world where a wife has to see things through her husband’s eyes. Clarissa’s indifference or ignorance to politics and “Armenians-Albanians” problem indicates two significant points. First, the female value is degraded in this social context, whereas Mrs. Dalloway’s party (her offering to life) is unimportant and her husband’s committee important. Second, women’s exclusion from politics and Parliament is explicit in Mrs. Dalloway’s bewilderment of social issues. To develop her individual and to retain her subjectivity, a woman needs Woolf’s demand of a room of one’s own and a mind of one’s own, which is the keynote of the two novels. However, the female multi-self isn’t merely derived from her divergent autonomy, but also from the fact that she has to play some roles to obtain her rights in the male-leading society. This element of “impersonation” is ubiquitous in either Mrs. Dalloway or The Hours[5, p.83]. In addition, Woolf’s portrait of women’s intimacy and Cunningham’s depiction of bisexuality reinforce the fluid sexuality that deviates from the dominant norm. When Woolf 15 speaks in favor of women’s fluid sexuality, Cunningham sets his focus apart from Woolf’s to concentrate on “the ambiguity of sexualorientation” [24, p.371]. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that they both endeavor to defend for the unconventional sexuality. With the discussion on the various kisses in the texts, I argue that the characters kiss each other to “feel connection,” to experience an affinity and intimacy [9, p.52]. Apparently, the sufferers and the outsiders (in comparison with the authority) have the mutual sympathy; therefore they incline to kiss each other to get a soothing relief. By guiding readers into Mrs. Dalloway’s stream of consciousness, Woolf reminds readers of the preliminary state of an individual, especially when readers are immersed in the heroine’s reverie. Although the two novelists write for the same purpose, they present their works in different ways. Woolf’s writing represents the depth, breadth, and wave of female consciousness and thoughts. Instead, Cunningham puts women’s desires and expectations into practice. Death is a part of life, a scary but strangely comforting reality. In Mrs. Dalloway, Big Ben tolls without feeling, reminding the heroine that she is one hour closer to the party, and ultimately one hour closer to death. We are always aware of our own temporal existence. It is this relentless reminder that shakes the heroine in the midst of life, and brings her back to the present. Putting herself into her characters, Woolf dealt with death through writing which became another consolation. This novel suggests that the only time humans truly appreciate life is in the face of death. “Death presents a future of uncertainty”. Face to face with the unknown, we search for purpose and meaning in life. In Mrs. Dalloway, Woolf turned death into something secretly desired, which allowed her to accept her own morbid feelings. “Without the consolation of religion, she, like her characters, struggled with the need to find significance and beauty in life and death” [15, p.57]. Instead of relying on a specific faith, Virginia Woolf managed to make 16 some sense out of life through writing. Well understanding the transparency and fragility of existence, she never took her right to exist for granted. Although Mental illness and personal tragedy ultimately led her to give up life, however strong her death impulses may have been, we can sense her ecstasy in life through her characters. The readers can take away a gleam of hope; even in total darkness, “there is a light always shining through”. Women issues, as the main theme in Mrs. Dalloway and The Hours, have changed with time in dimensional aspects. As the two novelists’ transitional milieus suggest, their concerns for women are influenced by their historical backgrounds in respective new epoch, and thus diverge from each other. In my study, the change and transformation of women questions through time are explored, together with the novelists’ dissimilar focuses on these problematics. After the analyses within the historical frame, I contend that women have suffered from a chronic persecution under the alignment of men, nationalism, doctors, armies, and empires. Hence women generate a collective experience of being oppressed. Consequently a female community is developed due to a sense of “we-ness.” Sharing a similar experience of being marginalized, the heroines have empathy for other women and the male outcasts. However, the male protagonists function differently in their relative contexts. Also, the male outsiders’ decision of death and the heroines’ determination of survival make a vivid contrast in relation to their attitudes toward life. I assert that women’s yearning for life derives from their long-lasting deprivation of the autonomy and the decision for their lives. By portraying the heroines’ survival, Cunningham intends to reveal the continuation of female life, from which a female genealogy is germinated. With a series of historical events, I provide an overall investigation of women problematics and the male Other during the time-span from the Victorian Age to the Postmodern Era. 17 2.2. Thomas Hardy heroines and their stereotypes We have it on his (Hardy's) own assurance that the Wessex of the novels and poems is practically identical with the Wessex of history, and includes the counties of Berkshire, Wilts(hire), Somerset, Hampshire, Dorset, and Devon — either wholly or in part. [8] Fortunately, some recent criticism has done a significant service to Hardy's A Pair of Blue Eyes in re-evaluating elements of the novel that have been traditionally reproached. For instance, in Thomas Hardy's Heroines: A Chorus of Priorities (1986), Pamela Jekel begins by observing that "in an exploration of the critical commentary available on the character of Elfride Swancourt, it seems clear that many reviewers have misunderstood--and consequently misrepresented--one of Hardy's most provocative and revealing heroines". Jekel recognizes that although critics like Norman Paige and D. H. Lawrence have made perceptive insights into Elfride's characterization, their arguments prove limiting and underestimate both her strength and complexity of character: Lawrence's implication is that, indeed, the tragedy is not very great at all, since Elfride has not had the strength to throw off even "the first little hedge of convention." In fact, the story of Elfride is at least poignant if not a classical tragedy, precisely because she does have the potential for such strength, because she does have many heroic qualities, and because she is betrayed by love--both false and true--and sadly, betrayed with her own complicity. Thus, the critic acknowledges that Hardy gives Elfride sufficient complexity that her striving for happiness and control over her life becomes heroic, "and that the inability of most to see that truth, creates Hardy's ironic tone and, ultimately, his pessimism"[34]. Although Jekel is at times critical of 18 Hardy's text, she recognizes and appreciates those elements of the novel that make it decidedly modern: "Hardy explores still-uncharted psychological frontiers, behaviours and explanations for them which were not then familiar. His instructive understanding of the reasons for Knight's 'spare love-making' and Elfride's distaste for Stephen's 'pretty,' almost feminine handsomeness, gives the novel a contemporary flavour in spite of its gothic construction"[16]. In Women and Sexuality in the Novels of Thomas Hardy (1988), Rosemarie Morgan sees A Pair of Blue Eyes as a radical text in which Hardy strikes back against the Victorian convention of regarding female sexuality as a pathological disorder and denying women a sexual reality . For her, the "contradictions and shifting perspectives"[14] which critics frequently cite as evidence of the novel's faulty construction are crucial to Hardy's textual strategy. Alternatively displacing and reinstating his heroine as he grapples with propriety on the one hand and an unconventional characterization on the other, Hardy ingeniously maps a course of increasingly fruitless voyages to mirror that unrewarding journey to womanhood which offers no prizes to the female challenger. [31] Morgan notes that only through a process of meticulous critical scrutiny can the novel's inconsistencies be understood as part of a literary stratagem that takes a radical approach to the exploration of gender issues: The more important part of this analysis... lies in the close attentive reading that is, to my mind, critical to an understanding of Hardy's radicalism, his defiance of convention, his rejection of prevailing sexual codes and practices, his commitment to the sexual reality of his women. [34] It is precisely because of the work of contemporary critics like Jekel and Morgan that A Pair of Blue Eyes has come to take its rightful place as an important early novel by Hardy. 19 In Women and Sexuality in the Novels of Thomas Hardy , Rosemarie Morgan provides an interesting footnote to Hardy's handling of Nemesis in Tess : Hardy's 'sadistic tale' does, of course, mete out punishment in equal measure: the fallen woman's true love is brought home from his 'Brazil' 'a mere yellow skeleton' condemned to live out his days with a 'spiritualized Tess' whom he may love but may not marry. And her seducer suffers death by her own hand, which plunges into his body a killing blade‹divine retribution surely [23] As a realist, Hardy felt that art should describe and comment upon actual situations, such as the heavy lot of the rural labourers and the bleak lives of oppressed women. Though the Victorian reading public tolerated his depiction of the problems of modernity, it was less receptive to his religious scepticism and criticism of the divorce laws. His public and critics were especially offended by his frankness about relations between the sexes, particularly in his depicting the seduction of a village girl in Tess , and the sexual entrapment and child murders of Jude. The passages which so incensed the late Victorians the average twentieth-century reader is apt to miss because Hardy dealt with delicate matters obliquely. The modern reader encounters the prostitutes of Casterbridge's Mixen Lane without recognizing them, and concludes somewhat after the 'Chase' scene in Tess that it was then and there that the rape occurred. In Hardy's novels female principals differ from one another far less than do his male principals. The temperamental capriciousness of such characters as Fancy Day, Eustacia Vye, and Bathsheba Everdene arises from an immediate and instinctive obedience to emotional impulse without sufficient corrective control of reason. Hardy's women rarely engage in such intellectual occupations as looking ahead. Of all of Hardy's women, surely it is Tess who has won the greatest respect for her strength of character and struggle to be treated as an individual. As W. R. Herman notes, Tess rejects both the past and the future that threaten to "engulf" her in favour of "the eternal now"[8], but these inexorable forces close in on her nonetheless at Stonehenge, symbol of the ever-present 20 past. Hardy's attitudes towards women were complex because of his own experiences. Certainly the latter stages of his own marriage to Emma Lavinia Gifford must have contributed much to his somewhat equivocal attitudes. On the one hand, Hardy praises female endurance, strength, passion, and sensitivity; on the other, he depicts women as meek, vain, plotting creatures of mercurial moods. As a young man, Hardy was easily infatuated, and easily wounded by rejection. Often he describes his bright and beautiful heroines, many drawn from such real-life figures as school-mistress Tryphena Sparks, at length: the blush of their cheeks, the arch of their eyebrows, their likeness to particular birds or flowers. Even modern female readers accept the truth of Hardy's female protagonists because, despite his implication that woman is the weaker sex, as Hardy remarked, "No woman can begrudge flattery." Even though Thomas Hardy asserted that he had sketched the outline of the novel's plot long before he met Emma Lavinia Gifford in March of 1870, various correspondences exist between his fiancée, an excellent equestrian with literary aspirations, and the heroine of his third published novel, A Pair of Blue Eyes, even though Elfride Swancourt is at least ten years younger. In Hardy (1994), Martin Seymour-Smith dismisses the tendency on the part of many Hardy enthusiasts over the years to identify Emma as the original of Elfride as "mostly superficial, and [concludes that ] Elfride cannot be taken as an exact portrait, except of Emma's appearance and circumstances and certain of her characteristics". She and Horace Moule, whom Hardy acknowledged to be the basis of Stephen Smith's rival, Henry Knight, never in fact met, so that Seymour-Smith's conclusion seems reasonable when applied to the novel's plot. However, in an interview with Saturday Review editor George Dewar shortly after Emma's death in 1912, Hardy admitted that Elfride's character was "largely" drawn from that of his late wife in the early days of their courtship; that "court" is the latter part of the heroine's surname may allude to that engagement, although the implications of the homonym "caught" cannot be 21 overlooked in connection with the pursuit of Elfride by four men. In all of Hardy's great novels there are frustrating, imprisoning marriages that may reflect his own first marriage. Though these relationships may seem almost 'sexless' to the modern reader, they are nevertheless quite believable. The "stale familiarity" that characterizes the relationship between young Susan and Michael Henchard as they trudge towards Weydon- Priors in the opening pages of The Mayor of Casterbridge is a nimbus that hangs over the unions of Eustacia and Clym inThe Return of the Native , Lucetta and Farfrae in The Mayor of Casterbridge , Bathsheba and Troy in Far from the Madding Crowd , and, of course, Jude and Arabella in Jude. The novelist, united in holy acrimony for all but three of the thirty-eight years of his first marriage, clearly saw the need and argued eloquently for reasonable and human divorce laws. Unsuitable matches in his novels inevitably lead to suffering for both partners. Early in the same year which saw the death of Emma Hardy, the novelist expressed the opinion in Hearst's Magazine (1912) that "the English marriage laws are. . . the gratuitous cause of at least half the misery of the community." There is a strong element of wish- fulfilment in Hardy's sparing Donald Farfrae in The Mayor of Casterbridge a protracted marriage to the egotistical and small-minded Lucetta. Hardy put so much of himself into his fiction that it is hardly surprising he gave it up for poetry after the hostile reception of his last and greatest novels, Tess and Jude. It was his cynical pessimism and social realism rather than his sympathy with his largely female protagonists that led him into difficulties. Hardy's heroes, like Clym and Jude and Henchard, are able to struggle actively with their destiny, form plans for opposing it, try to hew out a recognized place in the world. The women in his novels have no such outlet, and this makes their situation more tragic. They are limited to a very few, easily recognizable social roles, and they are always subject to sexual domination and 22 destruction from men [Merryn Williams, Thomas Hardy and Rural England : 90-91] Paul Turner in The Life of Thomas Hardy (1998) points out that the sum of two hundred pounds that Stephen deposits in Elfride's St. Kirrs Bank account from his work in India may have been suggested to Hardy by the advance that he himself negotiated with William Tinsley for writing the serial and threevolume novel that he would re-title A Pair of Blue Eyes. Further, Turner notes that Emma's snobbish father (John Attersoll Gifford) was at least as contemptuous of Hardy's proposal for his daughter's hand as is Rev. Swancourt of Stephen's. Turner speculates that the incident on the Cliff-Without-a-Name (in reality, Beechy Head on the English Channel) may have had its origin in a near-fatal accident that had befallen Emma at Tintagel. He concludes that "it was doubtless the heroine's association with Emma that made Hardy so fond of this particular novel"[13]. Neither Seymour-Smith nor Turner seems to have been aware when writing their biographies of Sulieman Ahmad's determination that Emma assisted Hardy materially in the composition of the novel by making fair-copy of his rough drafts and even by editing the diction of a number of passages. Biographer Robert Gittings convincingly argues that the fledgling novelist in 1872 mined his own conversations and correspondence with Emma Gifford for some pieces of Elfride's dialogue: if more of Emma's letters and diaries survived, it is likely that the resemblance would be startling. For instance, one of the few fragments from an Emma letter to Hardy is her comforting comment on her attitude toward such a reserved and withdrawn character as Hardy was: I take him (the reserved man) as I do the Bible: find out what I can, compare one text with another, & believe the rest in a simple lump of faith. In the middle of the novel, when Elfride is talking to the reserved and withdrawn literary man, Knight, who becomes unknowingly the younger 23 architect's rival, she says I suppose I must take you as I do the Bible--find out and understand all I can; and on the strength of that, swallow the rest in a lump, by simple faith. Since this is copied into the novel with only minor transpositions of words, we probably have a great deal of Emma's actual sayings in Elfride's dialogue, if we could recover them. [14, p. 235-56] Alluding to Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner , Hardy felt that "A story must be exceptional enough to justify its telling. We tale-tellers are all Ancient Mariners, and none of us is warranted in stopping Wedding Guests (in other words, the hurrying public) unless he has something more unusual to relate than the ordinary experience of every average man and woman." From Hardy's first ventures into fiction he had attempted "the adjustment of things unusual to things external and universal." Carl J. Webber notes the following characteristics of Hardy's fiction evident in what was probably a re-working of his first effort: 1. Its stage is chiefly set in rural Wessex. 2. It is topographically specific, to a degree unparalleled in English literature. 3. It deals with Dorset farmers, and shows sympathetic insight into the life of this class. 4. It does not avoid an impression of artificiality whenever "polite society" is involved. 5. The dialogue is often unreal, and there is occasional stiffness of language, with involved sentences, awkward inversions, split infinitives, etc. 6. In marked contrast with these rhetorical defects, there is frequent felicity of phrase, particularly in descriptive passages, and the author's alert senses, all of them, often leave their mark. 24 7. Nature interests him for her own sake, and his treatment of her is often poetic. 8. There are many literary allusions and quotations, and references to painters, musicians, and architects (in imitation of George Eliot). 9. The use of coincidents and accidents is overdone; and plausibility is often stretched to the extreme. 10. There is a secret marriage. 11. There is a pervading note of gloom, only momentarily relieved. 12. It all comes to a tragic end (sudden death). ALL these elements, discernible in 1886 ("Editorial Epilogue," An Indiscretion in the Life of an Heiress , Johns Hopkins Press, 1935: 145- 6). 25 CONCLUSION At the giving course paper we compared stereotyped women`s roles in Modern English Literature on the examples of Virginia Woolf's and Thomas Hardy's heroines. Women have evolved as both characters and writers in modern literature, compared to their limited characters and roles in classical literature. Reader and writers have matured, and the characters of both men and women have become more fully human. Women in particular are portrayed as rounder, more fully human people. Initially, I intended to discuss the complexities of oppression and insanity, looking at both the Great War veteran, Septimus Warren Smith and Mrs. Clarissa Dalloway, comparing the pressures of war and violence to suffering the transition of going from Clarissa to Mrs. Richard Dalloway, arguing that it is those that work continually to conform that are insane. Taking a humanist approach would have eclipsed the underlying feminist theme that women are criticized into behaving and, even then, aren’t taken seriously. Men are given some validity to fall back on. Although Smith commits suicide, he is given credit for his effort on the war front. Mrs. Dalloway receives no such praise. She is seen by even the man who obsessively loves her, Peter Walsh, as a woman who wastes her time holding frivolous parties. As Mrs. R. Dalloway, she busies herself maintaining the upper crust lifestyle. When reflecting on others and how they perceive her, she is Clarissa, and she recognizes that Peter criticizes her. All he has to do is look at her and she can feel it. There is a bit of her identity underneath the wedding ring and bourgeois façade. She silently stands by her interest in throwing society parties—it’s what she likes to do, and it’s something that gives her purpose. The same cannot be said for Smith’s wife, Lucrezia. She has trouble 26 separating herself from her husband’s plight, arguing that although Smith can be content without her, she can’t say the same for herself. Her view is odd, especially when considering how difficult it is for her to deal with his shell shock (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder). He is unbearable to live with, but she has conformed to the role of wife by suffering by his side, which drowns out her own identity. Criticism comes from many angles in our lives; parents who want to see us financially off, lovers who worry about our life choices, friends who want what’s best for us—but we learn from Mrs. Dalloway that the best reaction to such pressures is to preserve the self. Mrs. Dalloway is still clearly Clarissa, because she holds the party despite Peter’s criticisms. Her old friend, Sally Seton, although considered a radical in her youth, does not hold up to her true nature; she folds and eventually chalks her contribution to society as a mother of five sons, yes, five sons, she had five sons. For women, one of the best contemporary arguments to stand strong against pressures to conform to others and their standards comes from Paulo Coelho and his work, The Witch of Portobello. Although he is a male writer, he, like Virginia Woolf, provides space for the central female character to continue being true to herself. Although party planning is stressful, Clarissa validates herself. Coelho’s character Athena faces the reality of teaching others without any prior preparation and does it despite serious threats from the established religious institutions. In the end, things work out for both women because they do not listen to others. As women, we need to listen to ourselves and ignore both external and internal negatives which hamper our own growth. Men also face doubts and pressures which steer them away from their own dreams, but women face the double obstacle of the societal fear of the feminine. Coelho acknowledges that women through the ages have developed an intuition that men do not usually posses—so listen to it, use it, and deal with life accordingly. To do so is to 27 preserve self validation, whether it is through throwing upper crust parties or getting people to set aside their fears and live the way they want to. When Rosemarie Morgan claims, "Hardy's women ... must have confused many readers caught with mixed feelings of admiration and alarm," [17] she brings forward a duality of reaction which reflects Hardyan heroines' characters. The confusion she refers to can be understood within the novels' historical contexts, as these female protagonists were most likely to have been quite unusual at the time of their creation. Concomitantly, today's readers are likely to be perplexed while reading Thomas Hardy's novels, as his presentation of women seems to stand out from his contemporaries with his attempts at breaking down the stereotypical characters presented in his day. Hardy's women have their faults as well as their qualities and thus they become more complete and real. This complexity makes them more human; they are not representations of the ideal Victorian housewife who is characterised by her perfection at all times. They are not only confronted with their own problems and have to make reasoned decisions, but can be just as composed and feeble as their male counterparts. As Rosemarie Morgan's comment suggests these Hardyan women provoked varied emotions, through their trials and tribulations, and my aim is to explore in what way Hardy presents his female protagonists to entice such a varied palette of reactions. 28 REFERENCES 1. Attridge, Derek. “Molly’s flow: the writing of ‘Penelope’ and the question of women’s language.” Joyce Effects: On Language, Theory, and History. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2000. 93-116. 2. Benjamin, Walter. “The Flвneur.” Charles Baudelaire: A Lyric Poet in the Era of High Capitalism. Trans. Harry Zohn. London and New York: Verso, 1983. 35-66. 3. Bowlby, Rachel. “Walking, women, and writing: Virginia Woolf as flвneuse.” New Feminist Discourses: Critical Essays on Theories and Texts. Ed. Isobel Armstrong. London and New York: Routledge, 1992. 26-47. 4. Cecil, Lord David. Hardy The Novelist. London: Constable: 1954. 5. Cunningham, Michael. The Hours. London: Fourth Estate, 2002. Friedan, Betty. “The Problem That Has No Name.” The Feminine Mystique. New York: Norton, 1963. 15-32. 6. Guth, Deborah. “Rituals of Self-Deception: Clarissa Dalloway’s Final Moment of Vision.” Twentieth Century Literature 36.1 (1990): 35-42. 7. Herman, William R. "Hardy's Tess of the D’Urbervilles." Explicator 18, 3 (December 1959), item no. 16 8. Iannone, Carol. “Woolf, Women, and ‘The Hours’.” Commentary 115.4 (2003): 50-53. 9. Irigaray, Luce. This Sex Which Is Not One. Ithaca, New York: Cornell UP, 1985. 10. Juhasz, Suzanne. “Object Relations and Women’s Use of Language: Readings from British and American Psychology.” The Women and Language Debate: A Sourcebook. Ed. Camille Roman, Suzanne Juhasz, and Cristanne Miller. New Jersey: Rutgers UP, 1994. 107-18. 11. Lane, Christopher. “When Plagues Don’t End.” The Gay and 29 Lesbian Review 8.1 (2001): 30-32. 12. Lea, Hermann. Thomas Hardy's Wessex. London: Macmillan, St. Martin's Press, 1913 (rpt. 1928). 13. Lothe, Jakob. "Hardy's Authorial Narrative Method in Tess of the D'Urbervilles." The Nineteenth-Century British Novel. Ed. Jeremy Hawthorn. London: Edward Arnold, 1986. 157-170. 14. Marcus, Laura. “Woolf’s feminism and feminism’s Woolf.” The Cambridge Companion to Virginia Woolf. Ed. Sue Roe and Susan Sellers. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2000. 209-44. 15. Miller, Cristanne. “Who Says What to Whom?: Empirical Studies on Language and Gender.” The Women and Language Debate: a sourcebook. Ed. Camille Roman, Suzanne Juhasz, and Cristanne Miller. New Jersey: Rutgers UP, 1994. 267-79. 16. Moi, Toril. “Introduction.” The Kristeva Reader. Ed. Toril Moi. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1986. 1-22. 17. Morgan, Rosemarie. "Passive Victim? Tess of the D'Urbervilles." Thomas Hardy Journal 5, 1 (January 1989): 31-54. See her book, Women and Sexuality in the Novels of Thomas Hardy (New York: Routledge, 1988). 18. Peach, Linden. “‘National Conservatism’ and ‘Conservative Nationalism’: Mrs. Dalloway.” Virginia Woolf (Critical Issues). Basingstoke: Macmillan, 2000. 88-112. 19. Pinion, F. B. A Hardy Companion. London: Macmillan, St. Martin's Press, 1968. 20. Povalyaeva, Natalia. “The Issue of Self-Identification in Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway and Cunningham’s The Hours.” Woolf Across Cultures. Ed. Natalya Reinhold. New York: Pace UP, 2004. 269-76. 21. Rignall, John. “Benjamin’s Flвneur and the Problem of Realism.” The Problems of Modernity: Adorno and Benjamin. Ed. Andrew Benjamin. 30 London and New York: Routledge, 1989. 112-21. 22. Roman, Camille. “Female Sexual Drives, Subjectivity, and Language: The Dialogue with/beyond Freud and Lacan.” The Women and Language Debate: a sourcebook. Ed. Camille Roman, Suzanne Juhasz, and Cristanne Miller. New Jersey: Rutgers UP, 1994. 9-19. 23. Schiff, James. “Rewriting Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway: Homage, Sexual Identity, and the Single-Day Novel by Cunningham, Lippincott, and Lanchester.” Critique 45.4 (2004): 363-82. 24. Showalter, Elaine. “Beyond the Female Aesthetics: Contemporary Women Novelists.” A Literature of Their Own: British Women Novelists from Bronte to Lessing. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1999. 298-319. 25. Sim, Lorraine. “No ‘Ordinary Day’: The Hours, Virginia Woolf and Everyday Life.” Hecate 31.1 (2005): 60-70. 26. Smith, Marilyn Schwinn. “The Activist Pens of Virginia Woolf and Betty Friedan.” Woolf Across Cultures. Ed. Natalya Reinhold. New York: Pace UP, 2004. 63-76. 27. Spengler, Birgit. “Michael Cunningham Rewriting Virginia Woolf: Pragmatist vs. Modernist Aesthetics.” Woolf Studies Annual, Volume 10. Ed. Mark Hussey. New York: Pace UP, 2004. 51-79. 28. Spivey, Ted R. "Thomas Hardy's Tragic Hero." Nineteenth- Century Fiction 9 (1954-5): 179- 191. 29. Tanner, Tony. "Colour and Movement in Hardy's Tess of the d'Urbervilles." The Victorian Novel: Essays in Criticism , ed. Ian Watt. London: Oxford University Press, 1971. 30. Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: MLA, 1985. 31. Webber, Carl J. "Editorial Epilogue." An Indiscretion in the Life of an Heiress by Thomas Hardy. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1935. 32. Whitworth, Michael. “Virginia Woolf and Modernism.” The 31 Cambridge Companion to Virginia Woolf. Ed. Sue Roe and Susan Sellers. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2000. 146-63. 33. Williams, Merryn. Thomas Hardy and Rural England. London: Macmillan, 1972. 34. Winston, Jane. “Gender and sexual identity in the modern French novel.” The Cambridge Companion to The French Novel: From 1800 to the Present. Ed. Timothy Unwin. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1997. 223-41. 35. Wolff, Janet. “The Invisible Flвneuse: Women and the Literature of Modernity.” The Problems of Modernity: Adorno and Benjamin. Ed. Andrew Benjamin. London and New York: Routledge, 1989. 141-56. 36. Wood, Andelys. “Walking the Web in the Lost London of Mrs. Dalloway.” Mosaic: A Journal for the Interdisciplinary Study of Literature 36.2 (2003): 19-32. 37. Woolf, Virginia. “The Intellectual Status of Women.” A Woman’s Essays: Selected Essays. Vol. 1. Ed. Rachel Bowlby. London: Penguin, 1992. 30-39. 38. Wyatt, Jean. “Avoiding self-definition: In defense of women’s right to merge (Julia Kristeva and Mrs. Dalloway).” Women’s Studies 13.1 (1986): 115-26. 32