Running Head: PSYCHICAL DISTANCE

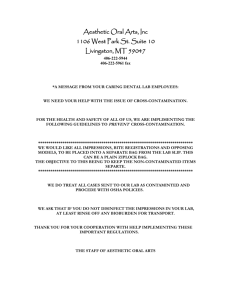

advertisement