I. New Criticism

advertisement

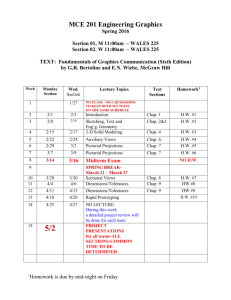

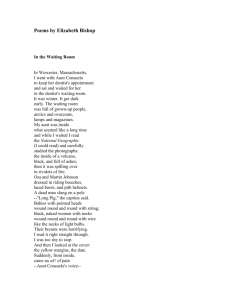

Literary Criticism: Form and Race Table of Content Type/Chapter 出 處 Titles Examples th- Some 19 Century Poems on Death and Separation Chap 1. New Criticism Theory “The Jilting of Granny Weatherall” Examples Ref. Examples 北島的詩 -- I IX Chap 2. Structuralism Chap 3 Structuralist Narratology Chap 4-1. Ref. Chap 4-2. Examples Theory+Example II “The Work of Representation” III 3. Semiotics 4. Discourse, Power & Subject Bishop’s “Sestina”& “The Map” “The Lesson” “The Purloined Letter” Theory Ref. Chap 6. Ref. Chap 7 Examples Ref. VII Deconstruction II Jameson on Postmodern VIII Culture “Hong Kong Prayer” & other -poems "The Blind Man" IX IV Postcolonialism Theory Chap 8 IV V VI “Text Play” Includes Daffodil poems Wordsworth’s and Dickenson’s X poems “The Babysitter” XI Ref. I 出 處 s II. Structuralism & Semiotics Theory Titles III. Postmodernism & Poststructuralism Ref. Chap 5. I. New Criticism p. Type Chap 9 Examples Postcolonial Criticism and XII Theory "English, National XIII Identity and Cultural Heritage." Excerpts from Robinson Crusoe XIV & Jane Eyre -"Good Advice is Rarer than XV Rubies" "Columbus in Chains" XVI "My Man Bovanne" 魚骸 VII XVII p. Sources: I. II. Literary Criticism: An Introduction to Theory and Practice. 2nd Ed. (Bressler, Charles E. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1999.) X. Reader's Guide to Contemporary Theory (Raman Seldon. Harvester, 93) XI. Pricksongs and Descants. American Library, 1969. III. Hall, Stuart. Excerpt from "The Work of Representation." 36-64. Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices. Ed. Stuart Hall. London: Sage, 1997. IV. Elizabeth Bishop. The Complete Poems: 1927-1979. NY: The Noonday P, 1995. V. IX. “The Blind Man. D. H. Lawrence. The Heath Introduction to Fiction. 4th Ed. Ed. John J. Clayton. Lexington, MA: D. C. Heath & Co, 1992. “The Lesson.” Toni Cade Bambara. The Heath Introduction to Fiction. 4th Ed. Ed. John J. Clayton. Lexington, MA: D. C. Heath & Co, 1992. VI. “The Purloined Letter.” Edgar Allan Poe. from The American Tradition in Literature. George Perkins ed. 8th Ed. McGrawHill, 1994. VII. Re-Reading Literature: New Critical Approaches to the Study of English. Sue Hackman & Barbara Marshall. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1990. VIII. 詹明信 (Fredric Jameson)﹒ 《後現代主義與文化理論》 ,唐 小兵譯,台北:合志, 1990. Practicing Theory and Reading Literature (Raman Seldon. Kentucky, 89) Robert Coover. XII. Literary Theory: The Basics. Routledge, 2001. NY: New Hans Bertens. XIII. Doing English: A Guide for Literature Students. Eaglestone. NY: Routledge, 2000. NY: Robert XIV. Texts and Contexts: introducing literature and language study. Adrian Beard. NY: Routledge, 2001 XV. East, West. Salman Rushdie. Toronto: Vintage, 1996. XVI. Kincaid, Jamaica. Giroux, 1983. XVII. 〈魚骸〉. Annie John. 黃錦樹. NY: Farr, Staus and Some 19th-Century Poems on Death and Separation Neutral Tones WHEN we two parted Thomas Hardy—1898 We stood by a pond that winter day, And the sun was white, as though chidden of God, And a few leaves lay on the starving sod; —They had fallen from an ash, and were gray. Your eyes on me were as eyes that rove Over tedious riddles of years ago; And some words played between us to and fro On which lost the more by our love. The smile on your mouth was the deadest thing Alive enough to have strength to die; And a grin of bitterness swept thereby Like an ominous bird a-wing . . . Since then, keen lessons that love deceives, And wrings with wrong, have shaped to me Your face, and the God-curst sun, and a tree, And a pond edged with grayish leaves. George Gordon Byron 1813 WHEN we two parted In silence and tears, Half broken-hearted To sever for years, Pale grew thy cheek and cold, Colder thy kiss; Truly that hour foretold Sorrow to this. The dew of the morning Sunk chill on my brow— It felt like the warning Of what I feel now. Thy vows are all broken, And light is thy fame: I hear thy name spoken, And share in its shame. They name thee before me, A knell to mine ear; A shudder comes o'er me— Why wert thou so dear? They know not I knew thee, Who knew thee too well: Long, long shall I rue thee, Too deeply to tell. In secret we met— In silence I grieve, That thy heart could forget, Thy spirit deceive. If I should meet thee After long years, How should I greet thee? With silence and tears. For Byron’s relationship with Lady Caroline Lamb, please see http://englishhistory.net/byron/lclamb.html The Going Thomas Hardy (Dec. 1912) Why did you give no hint that night That quickly after the morrow's dawn, And calmly, as if indifferent quite, You would close your term here, up and be gone Where I could not follow With wing of swallow To gain one glimpse of you ever anon! Never to bid good-bye, Or lip me the softest call, Or utter a wish for a word, while I Saw morning harden upon the wall, Unmoved, unknowing That your great going Had place that moment, and altered all. Why do you make me leave the house And think for a breath it is you I see At the end of the alley of bending boughs Where so often at dusk you used to be; Till in darkening dankness The yawning blankness, Of perspective sickens me! You were she who abode By those red-veined rocks far West, You were the swan-necked one who rode Along the beetling Beeny Crest, And, reining nigh me, Would muse and eye me, While Life unrolled us its very best. Why, then, latterly did we not speak, Did we not think of those days long dead, And ere your vanishing strive to seek That time's renewal? We might have said, "In this bright spring weather We'll visit together Those places that once we visited. Well, well! All's past amend, Unchangeable. It must go. I seem but a dead man held on end To sink down soon. . . . O you could not know That such swift fleeing No soul foreseeing— Not even I—would undo me so! A slumber did my spirit seal; I had no human fears: She seemed a thing that could not feel The touch of earthly years. No motion has she now, no force; She neither hears nor sees; Rolled round in earth's diurnal course, With rocks, and stones, and trees. William Wordsworth 1799 1. Composed in Germany. Coleridge wrote of this poem in a letter of April 1799: "Some months ago Wordsworth transmitted to me a most sublime Epitaph ... whether it had any reality, I cannot say.--Most probably, in some gloomier moment he had fancied the moment in which his Sister might die." Convergence of the Twain Thomas Hardy (Dec. 1912) (Lines on the loss of the 'Titanic') I In a solitude of the sea Deep from human vanity, And the Pride of Life that planned her, stilly couches she. II Steel chambers, late the pyres Of her salamandrine fires, Cold currents thrid, and turn to rhythmic tidal lyres. III Over the mirrors meant To glass the opulent The sea-worm crawls -- grotesque, slimed, dumb, indifferent. IV Jewels in joy designed To ravish the sensuous mind Lie lightless, all their sparkles bleared and black and blind. V Dim moon-eyed fishes near Gaze at the gilded gear And query: 'What does this vaingloriousness down here?'... VI Well: while was fashioning This creature of cleaving wing, The Immanent Will that stirs and urges everything VII Prepared a sinister mate For her -- so gaily great -A Shape of Ice, for the time far and dissociate. VIII And as the smart ship grew In stature, grace, and hue, In shadowy silent distance grew the Iceberg too. IX Alien they seemed to be: No mortal eye could see The intimate welding of their later history, X Or sign that they were bent By paths coincident On being anon twin halves of one august event, XI Till the Spinner of the Years Said 'Now!' And each one hears, And consummation comes, and jars two hemispheres. CHRISTINA ROSSETTI (1830-1894) –Three poems WHEN I AM DEAD, MY DEAREST Dec 1848 After Death The curtains were half drawn, the floor was swept And strewn with rushes, rosemary and may Lay thick upon the bed on which I lay, Where thro' the lattice ivy-shadows crept. He leaned above me, thinking that I slept And could not hear him; but I heard him say: "Poor child, poor child:" and as he turned away Came a deep silence, and I knew he wept. He did not touch the shroud, or raise the fold That hid my face, or take my hand in his, Or ruffle the smooth pillows for my head: He did not love me living; but once dead He pitied me; and very sweet it is To know he still is warm tho' I am cold. The Bourne Underneath the growing grass, Underneath the living flowers, Deeper than the sound of showers There we shall not counter the hours By the shadows as they pass. Youth and health will be but vain Beauty reckoned of no worth: There a very little girth Can hold round what once the earth Seemed too narrow to contain. When I am dead, my dearest, Sing no sad songs for me; Plant thou no roses at my head, Nor shady cypress tree: Be the green grass above me With showers and dewdrops wet; And if thou wilt, remember, And if thou wilt, forget. I shall not see the shadows, I shall not feel the rain; I shall not hear the nightingale Sing on, as if in pain: And dreaming through the twilight That doth not rise nor set, Haply I may remember, And haply may forget. Christina's brother and editor, William Michael Rossetti, commented: "This celebrated lyric ... has perhaps been oftener quoted, and certainly oftener set to music, than anything else by Christina Rossetti." And indeed there is a Chinese song, called〈歌〉—lyrics by 徐志摩,and music by 羅大佑。 Elizabeth Bishop Sestina September rain falls on the house. In the failing light, the old grandmother sits in the kitchen with the child beside the Little Marvel Stove, reading the jokes from the almanac, laughing and talking to hide her tears. She thinks that her equinoctial tears and the rain that beats on the roof of the house were both foretold by the almanac, but only known to a grandmother. The iron kettle sings on the stove. She cuts some bread and says to the child, It's time for tea now; but the child is watching the teakettle's small hard tears dance like mad on the hot black stove, the way the rain must dance on the house. Tidying up, the old grandmother hangs up the clever almanac on its string. Birdlike, the almanac hovers half open above the child, hovers above the old grandmother and her teacup full of dark brown tears. She shivers and says she thinks the house feels chilly, and puts more wood in the stove. It was to be, says the Marvel Stove. I know what I know, says the almanac. With crayons the child draws a rigid house and a winding pathway. Then the child puts in a man with buttons like tears and shows it proudly to the grandmother. The Map Land lies in water; it is shadowed green. Shadows, or are they shallows, at its edges showing the line of long sea-weeded ledges where weeds hang to the simple blue from green. Or does the land lean down to lift the sea from under, drawing it unperturbed around itself? Along the fine tan sandy shelf is the land tugging at the sea from under? The shadow of Newfoundland lies flat and still. Labrador's yellow, where the moony Eskimo has oiled it. We can stroke these lovely bays, But secretly, while the grandmother under a glass as if they were expected to blossom, busies herself about the stove, or as if to provide a clean cage for invisible fish. the little moons fall down like tears The names of seashore towns run out to sea, from between the pages of the almanac the names of cities cross the neighboring mountains into the flower bed the child -the printer here experiencing the same excitement has carefully placed in the front of the house. as when emotion too far exceeds its cause. These peninsulas take the water between thumb and finger Time to plant tears, says the almanac. like women feeling for the smoothness of yard-goods. The grandmother sings to the marvelous stove Mapped waters are more quiet than the land is, and the child draws another inscrutable lending the land their waves' own conformation: house. and Norway's hare runs south in agitation, profiles investigate the sea, where land is. Are they assigned, or can the countries pick their colors? -What suits the character or the native waters best. Topography displays no favorites; North's as near as West. More delicate than the historians' are the map-makers' colors.