Romantic Poetry Week Packet

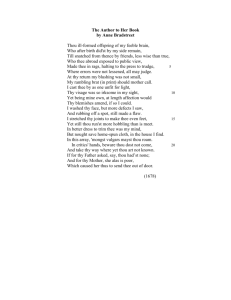

advertisement

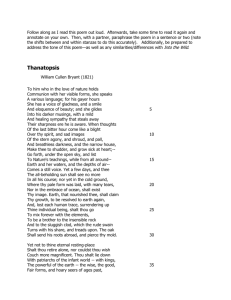

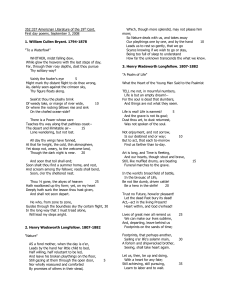

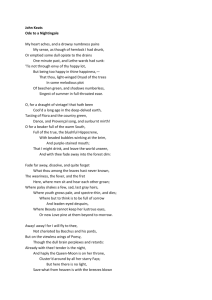

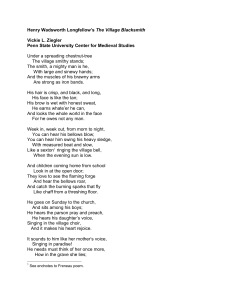

Day One Directions: 1. In your pod, you have information that suits three reading levels. Decide which reading will go to which group member. 2. Then, take notes as you read about Romanticism. 3. Your purpose is to find out what Romanticism was. 4. When you are all finished reading, share your information with your other group members. 5. We will go over the basics in the last ten minutes of class Notes from my reading (level _______________________ ): Notes from my group members: Day Two Directions: Read the Henry Wadsworth Longfellow reading in your small group. Write down the most important information in each paragraph (four main ideas). When you are finished, begin reading the two Longfellow poems. Finish reading them for homework. We will answer the reading questions in class. 1. 2. 3. 4. The Village Blacksmith by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Under a spreading chestnut-tree The village smithy stands; The smith, a mighty man is he, With large and sinewy hands; And the muscles of his brawny arms Are strong as iron bands. He goes on Sunday to the church, And sits among his boys; He hears the parson pray and preach, He hears his daughter's voice, Singing in the village choir, And it makes his heart rejoice. His hair is crisp, and black, and long, His face is like the tan; His brow is wet with honest sweat, He earns whate'er he can, And looks the whole world in the face, For he owes not any man. It sounds to him like her mother's voice, Singing in Paradise! He needs must think of her once more, How in the grave she lies; And with his hard, rough hand he wipes A tear out of his eyes. Week in, week out, from morn till night, You can hear his bellows blow; You can hear him swing his heavy sledge, With measured beat and slow, Like a sexton ringing the village bell, When the evening sun is low. Toiling,--rejoicing,--sorrowing, Onward through life he goes; Each morning sees some task begin, Each evening sees it close Something attempted, something done, Has earned a night's repose. And children coming home from school Look in at the open door; They love to see the flaming forge, And hear the bellows roar, And catch the burning sparks that fly Like chaff from a threshing-floor. Thanks, thanks to thee, my worthy friend, For the lesson thou hast taught! Thus at the flaming forge of life Our fortunes must be wrought; Thus on its sounding anvil shaped Each burning deed and thought A Psalm of Life by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Tell me not, in mournful numbers, Life is but an empty dream! For the soul is dead that slumbers, And things are not what they seem. Life is real! Life is earnest! And the grave is not its goal; Dust thou art, to dust returnest, Was not spoken of the soul. Not enjoyment, and not sorrow, Is our destined end or way; But to act, that each to-morrow Find us farther than to-day. Art is long, and Time is fleeting, And our hearts, though stout and brave, Still, like muffled drums, are beating Funeral marches to the grave. In the world’s broad field of battle, In the bivouac of Life, Be not like dumb, driven cattle! Be a hero in the strife! Trust no Future, howe’er pleasant! Let the dead Past bury its dead! Act,— act in the living Present! Heart within, and God o’erhead! Lives of great men all remind us We can make our lives sublime, And, departing, leave behind us Footprints on the sands of time; Footprints, that perhaps another, Sailing o’er life’s solemn main, A forlorn and shipwrecked brother, Seeing, shall take heart again. Let us, then, be up and doing, With a heart for any fate; Still achieving, still pursuing, Learn to labor and to wait. DAY THREE “The Village Blacksmith” Reading Questions 1. Is the picture of the blacksmith that Longfellow draws positive or negative? How does the poet characterize him? 2. The significance of the description of the forging activities in the first part of the poem only becomes clear near the end of the poem, with Longfellow’s reference to “the burning forge of life.” Keeping this last stanza in mind, what effect does Longfellow intend for the detail about the work of the blacksmith in the first part. 3. Why does the poet mention the family of the blacksmith? 4. How is this poem Romantic? “A Psalm of Life” Reading Questions 1. What parts of this poem reflect Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s attempt to define American identity? 2. What is Longfellow’s message in his poem and is this message still relevant today? 3. Which images in the poem strengthen and/or illuminate Longfellow’s message? 4. How is this poem Romantic? DAY FOUR Directions: Today, you will work as a group to write a one-page mini-essay. Prompt: What is the speaker’s view of life in “A Psalm of Life”? A good answer will include: o o o o o o an MLA header and a title an intro with a thesis that clearly answers the prompt two body paragraphs (each should have only one main idea) quotes from the poem to prove each main idea is correct clear transitions and strong vocabulary skills a conclusion (wrap up your answer in a final few lines) CITATION: o When citing poetry, you use line numbers instead of page numbers. o You use a slash (/) between each new line. o If you are using more than four lines, use a block quote (see citation packet for more information about block quotes). DAY FIVE Directions: Read the William Cullen Bryant reading in your small group. Write down the most important information in each paragraph (four main ideas). When you are finished, begin reading the two Bryant poems. Finish reading them for homework. We will answer the reading questions in class. 1. 2. 3. 4. Thanatopsis by William Cullen Bryant To him who in the love of nature holds Communion with her visible forms, she speaks A various language; for his gayer hours She has a voice of gladness, and a smile And eloquence of beauty; and she glides Into his darker musings, with a mild And healing sympathy that steals away Their sharpness ere he is aware. When thoughts Of the last bitter hour come like a blight Over thy spirit, and sad images Of the stern agony, and shroud, and pall, And breathless darkness, and the narrow house, Make thee to shudder, and grow sick at heart;-Go forth, under the open sky, and list To Nature's teachings, while from all around-Earth and her waters, and the depths of air-Comes a still voice. Yet a few days, and thee The all-beholding sun shall see no more In all his course; nor yet in the cold ground, Where thy pale form was laid, with many tears, Nor in the embrace of ocean, shall exist Thy image. Earth, that nourished thee, shall claim Thy growth, to be resolved to earth again, And, lost each human trace, surrendering up Thine individual being, shalt thou go To mix forever with the elements, To be a brother to the insensible rock And to the sluggish clod, which the rude swain Turns with his share, and treads upon. The oak Shall send his roots abroad, and pierce thy mold. Yet not to thine eternal resting-place Shalt thou retire alone, nor couldst thou wish Couch more magnificent. Thou shalt lie down With patriarchs of the infant world -- with kings, The powerful of the earth -- the wise, the good, Fair forms, and hoary seers of ages past, All in one mighty sepulchre. The hills Rock-ribbed and ancient as the sun, -- the vales Stretching in pensive quietness between; The venerable woods -- rivers that move In majesty, and the complaining brooks That make the meadows green; and, poured round all, Old Ocean's gray and melancholy waste,-Are but the solemn decorations all Of the great tomb of man. The golden sun, The planets, all the infinite host of heaven, Are shining on the sad abodes of death Through the still lapse of ages. All that tread The globe are but a handful to the tribes That slumber in its bosom. -- Take the wings Of morning, pierce the Barcan wilderness, Or lose thyself in the continuous woods Where rolls the Oregon, and hears no sound, Save his own dashings -- yet the dead are there: And millions in those solitudes, since first The flight of years began, have laid them down In their last sleep -- the dead reign there alone. So shalt thou rest -- and what if thou withdraw In silence from the living, and no friend Take note of thy departure? All that breathe Will share thy destiny. The gay will laugh When thou art gone, the solemn brood of care Plod on, and each one as before will chase His favorite phantom; yet all these shall leave Their mirth and their employments, and shall come And make their bed with thee. As the long train Of ages glides away, the sons of men-The youth in life's fresh spring, and he who goes In the full strength of years, matron and maid, The speechless babe, and the gray-headed man-Shall one by one be gathered to thy side, By those, who in their turn, shall follow them. So live, that when thy summons comes to join The innumerable caravan, which moves To that mysterious realm, where each shall take His chamber in the silent halls of death, Thou go not, like the quarry-slave at night, Scourged to his dungeon, but, sustained and soothed By an unfaltering trust, approach thy grave Like one who wraps the drapery of his couch About him, and lies down to pleasant dreams. The Prairies by William Cullen Bryant These are the gardens of the Desert, these The unshorn fields, boundless and beautiful, For which the speech of England has no nameThe Prairies. I behold them for the first, And my heart swells, while the dilated sight Takes in the encircling vastness. Lo! they stretch, In airy undulations, far away, As if the ocean, in his gentlest swell, Stood still, with an his rounded billows fixed, And motionless forever.- Motionless?No- they are all unchained again. The clouds Sweep over with their shadows, and, beneath, The surface rolls and fluctuates to the eye; Dark hollows seem to glide along and chase The sunny ridges. Breezes of the South! Who toss the golden and the flame-like flowers, And pass the prairie-hawk that, poised on high, Flaps his broad wings, yet moves not- ye have played Among the palms of Mexico and vines Of Texas, and have crisped the limpid brooks That from the fountains of Sonora glide Into the calm Pacific- have ye fanned A nobler or a lovelier scene than this? Man hath no power in all this glorious work: The hand that built the firmament hath heaved And smoothed these verdant swells, and sown their slopes With herbage, planted them with island groves, And hedged them round with forests. Fitting floor For this magnificent temple of the skyWith flowers whose glory and whose multitude Rival the constellations! The great heavens Seem to stoop down upon the scene in love,A nearer vault, and of a tenderer blue, Than that which bends above our eastern hills. As o'er the verdant waste I guide my steed, Among the high rank grass that sweeps his sides The hollow beating of his footstep seems A sacrilegious sound. I think of those Upon whose rest he tramples. Are they hereThe dead of other days?- and did the dust Of these fair solitudes once stir with life And burn with passion? Let the mighty mounds That overlook the rivers, or that rise In the dim forest crowded with old oaks, Answer. A race, that long has passed away, Built them;- a disciplined and populous race Heaped, with long toil, the earth, while yet the Greek Was hewing the Pentelicus to forms Of symmetry, and rearing on its rock The glittering Parthenon. These ample fields Nourished their harvests, here their herds were fed, When haply by their stalls the bison lowed, And bowed his maned shoulder to the yoke. All day this desert murmured with their toils, Till twilight blushed, and lovers walked, and wooed In a forgotten language, and old tunes, From instruments of unremembered form, Gave the soft winds a voice. The red man cameThe roaming hunter tribes, warlike and fierce, And the mound-builders vanished from the earth. The solitude of centuries untold Has settled where they dwelt. The prairie-wolf Hunts in their meadows, and his fresh-dug den Yawns by my path. The gopher mines the ground Where stood their swarming cities. All is gone; All- save the piles of earth that hold their bones, The platforms where they worshipped unknown gods, The barriers which they builded from the soil To keep the foe at bay- till o'er the walls The wild beleaguerers broke, and, one by one, The strongholds of the plain were forced, and heaped With corpses. The brown vultures of the wood Flocked to those vast uncovered sepulchres, And sat unscared and silent at their feast. Haply some solitary fugitive, Lurking in marsh and forest, till the sense Of desolation and of fear became Bitterer than death, yielded himself to die. Man's better nature triumphed then. Kind words Welcomed and soothed him; the rude conquerors Seated the captive with their chiefs; he chose A bride among their maidens, and at length Seemed to forget- yet ne'er forgot- the wife Of his first love, and her sweet little ones, Butchered, amid their shrieks, with all his race. Thus change the forms of being. Thus arise Races of living things, glorious in strength, And perish, as the quickening breath of God Fills them, or is withdrawn. The red man, too, Has left the blooming wilds he ranged so long, And, nearer to the Rocky Mountains, sought A wilder hunting-ground. The beaver builds No longer by these streams, but far away, On waters whose blue surface ne'er gave back The white man's face- among Missouri's springs, And pools whose issues swell the OregonHe rears his little Venice. In these plains The bison feeds no more. Twice twenty leagues Beyond remotest smoke of hunter's camp, Roams the majestic brute, in herds that shake The earth with thundering steps--yet here I meet His ancient footprints stamped beside the pool. Still this gret solitude is quick with life. Myriads of insects, gaudy as the flowers They flutter over, gentle quadrupeds, And birds, that scarce have learned the fear of man Are hear, and sliding reptiles of the ground, Startlingly beautiful. The graceful deer Bounds to the wood at my approach. The bee, A more adventurous colonist than man, With whom he came across the eastern deep, Fills the savannas with his murmurings, And hides his sweets, as in the golden age, Within the hollow oak. I listen long To his domestic humn, and think I hear The sound of that advancing multitude Which soon shall fill these deserts. From the ground Comes up the laugh of children, the soft voice Of maidens, and the sweet and solemn hymn Of Sabbath worshippers. The low of herds Blends with the rustling of the heavy grain Over the dark-brown furrows. All at once A fresher wind sweeps by, and breaks my dream, And I am in the wilderness alone.