Ode on a Grecian Urn

advertisement

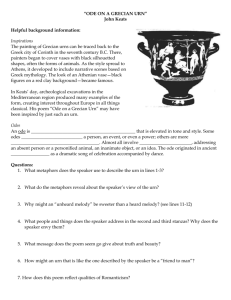

Ode on a Grecian Urn-John Keats Ode the description of a particularized outer natural scene; an extended meditation, which the scene stimulates, and which may be focused on a private problem or a universal situation or both; the occurrence of an insight or vision, a resolution or decision, which signals a return to the scene originally described, but with a new perspective created by the intervening meditation. Wordsworth's "Ode: Intimations of Immortality," Coleridge's "Dejection: An Ode," and Shelley's "Ode to the West Wind," are examples, and Keats' "Ode to a Nightingale," while Horatian in its uniform stanzaic form, reproduces the architectural format of the meditative soliloquy, or, it may be, intimate colloquy with a silent auditor. Adapted from A Guide to the Study of Literature: A Companion Text for Core Studies 6, Landmarks of Literature, ©Brooklyn College. "Ode on a Grecian Ode" is based on a series of paradoxes and opposites: the discrepancy between the urn with its frozen images and the dynamic life portrayed on the urn, the human and changeable versus the immortal and permanent, participation versus observation, life versus art. As in "Ode to a Nightingale," the poet wants to create a world of pure joy, but in this poem the idealized or fantasy world is the life of the people on the urn. Keats sees them, simultaneously, as carved figures on the marble vase and live people in ancient Greece. Existing in a frozen or suspended time, they cannot move or change, nor can their feelings change, yet the unknown sculptor has succeeded in creating a sense of living passion and turbulent action. As in "Ode to a Nightingale," the real world of pain contrasts with the fantasy world of joy. Initially, this poem does not connect joy and pain. The poem's structure reminds one of a five paragraph essay: (1) The first stanza introduces us to the topic, the picture on the urn, and presents several questions; (2) The second stanza speaks of music and love; (3) The third stanza continues with music, nature and love; (4) Stanza four deals with religion and sacrifice; (5) Stanza five gives a recap of the problem and the descriptions, followed by the truth revealed by the Urn--that beauty outlasts all. The first 4 lines define the subject of the stanza and the remaining 6 lines develop the idea Analysis Stanza I. Stanza I begins slowly, asks questions arising from thought and raises abstract concepts such as time and art. The comparison of the urn to an "unravish'd bride" functions at a number of levels. It prepares for the impossisbility of fulfillment of stanza II and for the violence of lines 8-10 of this stanza. The poem is a prolonged apostrophe to an ancient piece of Greek pottery, on one side of which is the image of a maiden amorously pursued by a lover. The situation presents a series of paradoxes rich in ambiguity. "Still" embodies two concepts--time and motion--which appear in a number of ways in the rest of the poem. They appear immediately in line 2 with the urn as a "foster" child. The urn exists in the real world, which is mutable or subject to time and change, yet it and the life it presents are unchanging; hence, the bride is "unravish'd" and as a "foster" child, the urn is touched by "slow time," not the time of the real world. The figures carved on the urn are not subject to time, though the urn may be changed or affected over slow time. The urn as "sylvan historian" speaks to the viewer, even if it doesn't answer the poet's questions (stanzas I and IV). Whether the urn communicates a message depends on how you interpet the final stanza. The urn is "sylvan"--first, because a border of leaves encircles the vase and second because the scene carved on the urn is set in woods. The "flowery tale" told "sweetly" and "sylvan historian" do not prepare for the terror and wild sexuality unleashed in lines 8-10 (another opposition); the effect and the subject of the urn or art conflict. Is it paradoxical that the urn, which is silent, tells tales "more sweetly than our rime"? Twice (lines 6 and 8) the poet is unable to distinguish between mortal and immortal, men and gods, another opposition; is there a suggestion of coexistence and inseparableness in this blurring of differences between them? With lines 8-10, the poet is caught up in the excited, rapid activities depicted on the urn and moves from observer to participant in the life on the urn, in the sense that he is emotionally involved. Paradoxically, turbulant dynamic passion is convincingly portrayed on cold, motionless stone. Line 3, sylvan: pertaining to or living in the woods; hence, a sylvan historian records scenes in the woods. Line 8, Tempe: a beautiful valley in Greece, it was sacred to Apollo, the god of poetry and music. Arcady: the literary word for Arcadia, in the central Peloponnesus. Zeus was born there, in one account. The word connotes a place of rural peace and simplicity because of the ancient reputation of its inhaitants as innocent and peaceful. Line 10, timbrels: ancient tambourines Keats introduces the poem with the first stanza by praising the urn, flattering it as if he wants something from it. Thus, he immediately gives the urn a humane quality by calling it an her but also complimenting it on its purity through "unravished bride." He is also saying that she is quiet and timeless as in "slow time" as if he has forgotten that she is an inanimate object. As the third line begins, he describes the urn as made of wood and knowing many stories, myths, of Ancient Greece as in "Sylvan," meaning woody, "historian." Thus, continuing, Keats is staring at the urn and beckoning it to reveal to him some stories, possibly through the pictures engraved in the urn, as in "legend haunts about thy shapein Tempe orArcady." Arcadia is a city in Ancient Greece and is reputed to have been isolated from civilization and is considered a paradise. These two cities are also significant because of their associations with Apollo and Zeus, respectively. Thus, when Keats says that the urn knows some stories from there is to 1. The poem begins with an apostrophe to "thou still unravish'd bride of quietness" (1). This is a metaphor comparing a maiden to the urn, which has not been tainted by neither impurities or, as the next line implies, time. The urn is then compared to a woodlands historian, who is able to tell a tale much more clearly than even a poet. 2. The poet uses rhetorical questions in the second half of the first stanza, questions he attempts to answer in the remainder of the poem. We apprehend the difference between a work of art that is frozen both in movement and time and ourselves - living creatures who must age, wither and die. Despite its antiquity, the urn has remained fresh, beautiful and intact like the female painted on one of its side. It is unmoving and silent since it is an object without voice or life. It is a "foster child" of Time because all Time's natural children are subject to mutability. Stanza II. The first four lines contrast the ideal (in art, love, and nature) and the real; which does Keats prefer at this point? What is the paradox of unheard pipes? Is this an oxymoron? The last six lines contrast the drawback of frozen time; note the negative phrasing: "canst not leave," "nor ever can," "never, never canst" in lines 5-8. Keats says not to grieve; whom he is addressing--the carved figures or the reader? or both? Then he lists the advantages of frozen time; however, Keats continues to use negative phrasing even in these lines: "do not grieve," "cannot fade," and ""hast not thy bliss." Keats may have made a mistake, or there may be a reason for this negative undertone, a reason which will become clear as the poem continues. Line 3, sensual ear: ear of the senses, i.e., they hear. The second stanza continues beckon to the urn to reveal its stories since it seems to be unrevealed as of the moment. Also, Keats seems to convincing to the urn that he is worthy to hear the story because he is "more endear'd" than other people. Hence, he is displayed as bored with other stories and seems to ask the urn to excite him with something innovative. He also uses "pipe to the spirit ditties of no tone" to continue with his flattery since a ditty is a poem that is meant to be sung and in this case he describes it with spirit to exalt it above a typical ditty. Thus, if that poem is considered to have "no tone," then the urn's story must be really magnificent and prodigious, which probably is a complete exaggeration as to lure the story out of the urn. Then, Keats describes the etchings in the urn, which is probably the story that the urn has finally consented to reveal. This is because Keats uses a colon after "tone" and seems to show the urn's consenting through this punctuation. He tells of a pretty young girl, under some trees and says that it can never leave "thy song" or can the trees beneath her shed leaves since they are engraved and immortalized in the wood. On the other hand, he mentions the cons of staying engraved in the urn by saying that this girl who is in love with a man can never get him though she can be close. But Keats also comforts the girl and continues with his rambling about how she should not grieve since she will never disappear, die, or grow old as in "cannot fade" and "be fair." She will love her lover forever. Rhyme scheme: ababcdeced Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard / Are sweeter" (1-2). This reminds me of Plato's forms. There is a perfect music in existence somewhere; all other music seeks to replicate it, yet falls short. This perfect music exists on the urn. It is not the sensual ear that perfection appears to, but the soul (13). Stanza III. This stanza recapitulates ideas from the preceding two stanzas and re-introduces some figures: the trees which can't shed leaves, the musician, and the lover. Keats portrays the ideal life on the urn as one without disappointment and suffering. The urn-depicted passion may be human, but it is also "all breathing passion far above" because it is unchanging. Is there irony in the fact that the superior passion depicted on the urn is also unfulfillable, that satisfaction is impossible? How does he portray real life, actual passion in the last three lines? Which is preferable, the urn life or real life? Note the repetition of the word "happy." Is there irony in this situation? In the third stanza, he continues to praise the urn's long- lasting beauty by commenting on how the tree leaves engraved in the urn can never fall nor can the seasons ever change. Thus, with so many parallels, the reader can confidently say that when Keats talks about songs he means it as a synonym for poem or story. He uses songs to represent the sweetness of discovering these stories. He also continues with complimenting how the stories or "songs" never gets old with its stories of "human passion" that causes humans to feel great emotion almost to the point of excessiveness. Thus, in this stanza, Keats seems to be overly sanguine and sentimental about the trees' conditions, through his constant repetition of "happy" and use of exclamation points, that he seems to be almost spurious or envious of the happiness that the trees have of unwavering beauty. ababcdecde Stanza IV. Stanza IV shows the ability of art to stir the imagination, so that the viewer sees more than is portrayed. The poet imagines the village from which the people on the urn came. In this stanza, the poet begins to withdraw from his emotional participation in and identification with life on the urn. This stanza focuses on communal life (the previous stanzas described individuals). What paradox is implicit in the contrast between the event being a sacrifice and the altar being "green"? between leading the heifer to the sacrifice and her "silken flanks with garlands drest"? Then in the fourth stanza, Keats tells of another story or depiction on the urn. He tells of a priest sacrificing a heifer, but Keats is about why people have come out of this citadel. Then, he says that he will never know since the people in the citadel are always silent and cannot tell him anything. In imagining an empty town, why does he give three possible locations for the town, rather than fix on one location? Why does he use the word "folk," rather than "people"? Think about the different connotations of these words. The image of the silent, desolate town embodies both pain and joy. How is it ironic that not a soul can tell us why the town is empty and that the vase communicates so much to the poet and so to the reader? Is this also paradoxical? In terms of the theme of pain-joy, what is Keats saying in lines 1-4, which describe the procession? in the rest of the stanza which describes the desolate town? Is he describing a temporary or a permanent condition? Is the viewer, who is the poet as well as the reader, pulled into the world of the urn? ababcdecde Stanza V. The poet observes the urn as a whole and remembers his vision. Is he emotionally involved in the life of the urn at this point, or is he again the observer? What aspect of the urn is stressed in the phrases "marble men and maidens," "silent form," and "Cold Pastoral"? Is there a paradox in the phrase "Cold Pastoral"? Yet the poet did experience the life experienced on the urn and comments, ambiguously perhaps, that the urn "dost tease us out of thought / As doth eternity." Is this another reference to the "dull brain" which "perplexes and retards" ("Ode to a Nightingale")? Why does Keats use the word "tease"? By teasing him "out of thought," did the urn draw him from the real world into an ideal world, where, if there was neither imperfection nor change, there was also no real life or fulfillment? Or, possibly, was the poet so involved in the life of the urn that he couldn't think? Was the urn an escape, however temporary, from the pains and problems of life? One thing that all these suggestions mean is that this is a puzzling line. In the final couplet, is Keats saying that pain is beautiful? You must decide whether it is the poet (a persona), Keats (the actual poet), or the urn speaking. Are both lines spoken by the same person, or does some of the quotation express the view of one speaker and the rest of the couplet express the comment upon that view by another speaker? Who is being addressed--the poet, the urn, or the reader? Are the concluding lines a philosphical statement about life or do they make sense only in the context of the poem? Click here to read the three versions of the last two lines. Some critics feel that Keats is saying that Art is superior to Nature. Is Keats thinking or feeling or talking about the urn only as a work of art? Your reading on this issue will be affected by your decision about who is speaking. Finally, in the last stanza, Keats talks about the "Attic" shape as in Athens and the beautiful decorations of the urn. He also talks about how staring at the urn makes him contemplate about how "beauty is truth, truth beauty,"' as he mulls over the thought that he would never be eternal. These last two lines are controversial since experts argue about who Keats is actually talking to and what the lines are about. Possibilities include poet to reader, urn to reader, poet to urn, or poet to figures on the urn. Personally, it seems to be urn to Keats, and then Keats quotes the urn to the readers. Clearly, the last two lines of the poem "beauty is truth, truth beauty," that is all ye know on earth, and all ye need to know' seems to epitomize this poem. In other words, it seems to be saying that since the urn is immutable and made of nature, it is beautiful and will never lie. Thus, this seemingly optimistic poem has a pessimistic tone as it insults humans as being untrue since humans always change. It also seems to praise youth for being beautiful, truthful, and innocent. That is, the urn seems to warn of untruthfulness in the world. Therefore, since mankind can never stay beautiful and youthful, then all humans are untruthful. Stanza five leaves us with our own questions that will not be answered. The speaker realizes that the freeze frame aspect of his subject is a "Cold Pastoral" cold as marble to the touch of livng hand - beautiful, immutable but unsatisfactory to breathing, panting human passion. An inescapable aspect of humanity is the wasting of age and oncoming mortality. The most difficult portion of the poem to explicate is its final couplet about Truth and Beauty being synonyms or denotations of the same abstract quality. T. S. Eliot has said the line is "a blemish on a beautiful poem" and adds that the problem may simply be that he fails to understand it. Critics John Middleton Murry and Heathcote Garrod agree. with Eliot. A thing of beauty is what it is, and what a thing is is a manifestation of uncontestable reality and Truth. Both Beauty and Truth lie beyond the possibility of alteration and of simplistic paraphrase, and therein resides their true and unchanging beauty. ababcdecde No matter how you read the last two lines, do they really mean anything? do they merely sound as if they mean something? or do they speak to some deep part of us that apprehends or feels the meaning but it is an experience/meaning that can't be put into words? Do they make a final statement on the relation of the ideal to the actual? Is the urn rejected at the end? Is art--can art ever be--a substitute for real life? What, if anything, has the poet learned from his imaginative vision of or daydream participation in the life of the urn? Does Keats, in this ode, follow the pattern of the romantic ode? Line 1, Attic: Grecian. Attica is in the central part of Greece where Athens was located. brede: embroidery. Line 2, overwrought: covered with. Line 5, cold pastoral: pastoral story in marble. pastoral: (1)pertaining to shepherds; hence it connotes simple, peaceful country life and the qualities associated with such a life, e.g., naturalness and innocence. (2) a kind of poem which praises the virtues of country living (simplicity, innocence, etc.). "Ode on a Grecian Urn" Analysis: Observations 3. Rhyme Scheme: ababcdedce, ababcdeced, ababcdecde, ababcdecde, ababcdecde 4. Rhythm: iambic pentameter 5. " Lines 15-20 give a description of the ideal. It is the form of beauty, of youth, of music that remains engraved upon the urn, the enacting of which would lessen its perfection. It's a beauty that has existed before objects. 6. Stanza 3 - The trees will never go old and deteriorate. The picture on the urn is Edenic. Evil has not been introduced. it does not go through the cycle of life where all deteriorates. 7. Eternity speaks in the final six lines of the poem: the entire scene is beauty, which has no beginning and no end, just like truth. 8. The last two lines: "that is all / Ye know on Earth, and all ye need to know." Does this indicate that there is more we learn after our life on Earth? by Alisa Trumann Ode on a Grecian Urn is one of the five great odes that John Keats (1795- 1821), an English poet that was part of the Romantic Movement, wrote in 1819. The odes, in the order written, were about psyche, nightingale, Grecian urn, melancholy, and autumn. This one, similar to the other odes, is about the beauty of the subject, and he expresses this idea by using adjectives freely and extravagantly in this sensuous iambic pentameter. Thou still unravish'd bride of quietness, Thou foster-child of silence and slow time, Sylvan historian, who canst thou express A flowery tale more sweetly than our rhyme: What leaf-fring'd legend haunt about thy shape Of deities or mortals, or of both, In Tempe or the dales of Arcady? What men or gods are these? What maidens loth? What mad pursuit? What struggle to escape? What pipes and timbrels? What wild ecstasy? Keats introduces the poem with the first stanza by praising the urn, flattering it as if he wants something from it. Thus, he immediately gives the urn a humane quality by calling it an her but also complimenting it on its purity through "unravished bride." He is also saying that she is quiet and timeless as in "slow time" as if he has forgotten that she is an inanimate object. As the third line begins, he describes the urn as made of wood and knowing many stories, myths, of Ancient Greece as in "Sylvan," meaning woody, "historian." Thus, continuing, Keats is staring at the urn and beckoning it to reveal to him some stories, possibly through the pictures engraved in the urn, as in "legend haunts about thy shapein Tempe orArcady." Arcadia is a city in Ancient Greece and is reputed to have been isolated from civilization and is considered a paradise. These two cities are also significant because of their associations with Apollo and Zeus, respectively. Thus, when Keats says that the urn knows some stories from there is to say that the urn is excessively knowledgeable and depicts Keats as a sycophant. Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard Are sweeter: therefore, ye soft pipes, play on; Not to the sensual ear, but, more endear'd, Pipe to the spirit ditties of no tone: Fair youth, beneath the trees, thou canst not leave Thy song, nor ever can those trees be bare; Bold lover, never, never canst thou kiss, Though winning near the goal - yet, do not grieve; She cannot fade, though thou hast not thy bliss, For ever wilt thou love, and she be fair! The second stanza continues beckon to the urn to reveal its stories since it seems to be unrevealed as of the moment. Also, Keats seems to convincing to the urn that he is worthy to hear the story because he is "more endear'd" than other people. Hence, he is displayed as bored with other stories and seems to ask the urn to excite him with something innovative. He also uses "pipe to the spirit ditties of no tone" to continue with his flattery since a ditty is a poem that is meant to be sung and in this case he describes it with spirit to exalt it above a typical ditty. Thus, if that poem is considered to have "no tone," then the urn's story must be really magnificent and prodigious, which probably is a complete exaggeration as to lure the story out of the urn. Then, Keats describes the etchings in the urn, which is probably the story that the urn has finally consented to reveal. This is because Keats uses a colon after "tone" and seems to show the urn's consenting through this punctuation. He tells of a pretty young girl, under some trees and says that it can never leave "thy song" or can the trees beneath her shed leaves since they are engraved and immortalized in the wood. On the other hand, he mentions the cons of staying engraved in the urn by saying that this girl who is in love with a man can never get him though she can be close. But Keats also comforts the girl and continues with his rambling about how she should not grieve since she will never disappear, die, or grow old as in "cannot fade" and "be fair." She will love her lover forever. Ah, happy, happy boughs! that cannot shed Your leaves, nor ever bid the spring adieu; And, happy melodist, unwearied, For ever piping songs for ever new; More happy love! more happy, happy love! For ever warm and still to be enjoy'd, For ever panting, and for ever young; All breathing human passion far above, That leaves a heart high-sorrowful and cloy'd, A burning forehead, and a parching tongue. In the third stanza, he continues to praise the urn's long- lasting beauty by commenting on how the tree leaves engraved in the urn can never fall nor can the seasons ever change. Thus, with so many parallels, the reader can confidently say that when Keats talks about songs he means it as a synonym for poem or story. He uses songs to represent the sweetness of discovering these stories. He also continues with complimenting how the stories or "songs" never gets old with its stories of "human passion" that causes humans to feel great emotion almost to the point of excessiveness. Thus, in this stanza, Keats seems to be overly sanguine and sentimental about the trees' conditions, through his constant repetition of "happy" and use of exclamation points, that he seems to be almost spurious or envious of the happiness that the trees have of unwavering beauty. Who are these coming to the sacrifice? To what green altar, O mysterious priest, Lead'st thou that heifer lowing at the skies, And all her silken flanks with garlands drest? What little town by river or sea shore, Or mountain-built with peaceful citadel, Is emptied of this folk, this pious morn? And, little town, thy streets for evermore Will silent be; and not a soul to tell Why thou art desolate, can e'er return. Then in the fourth stanza, Keats tells of another story or depiction on the urn. He tells of a priest sacrificing a heifer, but Keats is about why people have come out of this citadel. Then, he says that he will never know since the people in the citadel are always silent and cannot tell him anything. O Attic shape! Fair attitude! with brede Of marble men and maidens overwrought, With forest branches and the trodden weed; Thou, silent form, dost tease us out of thought As doth eternity: Cold Pastoral! When old age shall this generation waste, Thou shalt remain, in midst of other woe Than ours, a friend to man, to whom thou say'st, "Beauty is truth, truth beauty," - that is all Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know. Finally, in the last stanza, Keats talks about the "Attic" shape as in Athens and the beautiful decorations of the urn. He also talks about how staring at the urn makes him contemplate about how "beauty is truth, truth beauty,"' as he mulls over the thought that he would never be eternal. These last two lines are controversial since experts argue about who Keats is actually talking to and what the lines are about. Possibilities include poet to reader, urn to reader, poet to urn, or poet to figures on the urn. Personally, it seems to be urn to Keats, and then Keats quotes the urn to the readers. Clearly, the last two lines of the poem "beauty is truth, truth beauty," - that is all ye know on earth, and all ye need to know' seems to epitomize this poem. In other words, it seems to be saying that since the urn is immutable and made of nature, it is beautiful and will never lie. Thus, this seemingly optimistic poem has a pessimistic tone as it insults humans as being untrue since humans always change. It also seems to praise youth for being beautiful, truthful, and innocent. That is, the urn seems to warn of untruthfulness in the world. Therefore, since mankind can never stay beautiful and youthful, then all humans are untruthful. Source: http://englishhistory.net/keat s/poetry/odeonagrecianurn.html http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/J ohn_Keats www.dictionary.com Source: http://englishhistory.net/keat s/poetry/odeonagrecianurn.html by Kerry Michael Wood The intellectual and emotional appeal of Keats's "Ode on a Grecian Urn" prohibit wasting words on the author's biography and the mechanics of his prosody. All commentary should attempt recapitulation of the impact and tonality of fifty-one lines that ring with universal meaning and symphonic resonance. The salutation: "Thou still unravished bride of quietness" exploits three meanings of the word "still." The adjective means both "unmoving" and "silent"; as an adverb, it means " as yet," or "till the present time." In the same sentence, "sylvan" denotes forests and the pastoral elements associated with the place names Tempe and Arcady mentioned a few lines further on. The poet says that the urn tells its tale more sweetly than does his own rhyming. This returns us to the duplicitous realm of paradox. How can a historian or truth-teller be still, silent, mute, a "bride of quietness"? Is a "sylvan historian" a forest-dwelling rustic or is the poet calling the urn an expert on matters involved with the pastoral world. As usual, the answer is both. The lovers will never touch one another, yet they enjoy a relationship that is forever warm, still happily in anticipatory, forever panting, forever young. Though the urn's images do not move, the depicted action is dynamic. Thus works of art enable humankind to transcend mortality and contemplate changeless perfection and eternity. So also soundless pipes play, not to the ear but to the spirit, sweeter music than what can be heard. Audible melodies mayl be sweet, but sweeter are the toneless airs piped not to the ear but to the soul or spirit. Midway through the second stanza, the speaker turns his own and our attention to one of the scenes that decorate the urn. We see (but do not hear) a youth playing music on pipes while another "bold lover" pursues a fair maiden. Close as the amorous swain is to possessing his prize, he will never attain it, nor will he fail. His eagerness (read lust, if you will) will never diminish nor will the sensual beauty and allure of the maiden he intends to ravish. With the third stanza and its six iterations of the word "happy," the speaker exults in the frozen moment. The maid will lose neither beauty nor maidenhead; her ardent swain will never find release of ardor; the piper will not weary of piping; the boughs will never shed their leaves. Because a work of art is lifeless, it is also deathless. The previous images of silent stillness are resurrected in plant life being unable "to bid the spring adieu." The situation is more ideal than "breathing human passion" because never will there be consummation. The key word here is the speaker choice of "cloyed," meaning surfeited with enjoyment or sweetness. To be cloyed is to have happiness multiplied. A concomitant of consummation is exhaustion. Reaching a summit is necessarily followed by subsequent descent. But that is a fact of life, not of art. Instead of contemplating a negative, the speaker now considers the scene depicted on the other side of the urn. There we see not a drama of aspiration and desire but a priest leading a ceremonially garlanded heifer to be sacrificed. The priest is "mysterious" by virtue of being an initiate to such religious rituals. Following him are the inhabitants of some town, which therefore is deserted, all its citizenry piously proceeding to some "green altar." In stanza one we heard questions addressed to the urn. What leaf-fringed legend haunts about thy shape Of deities or mortals, or of both.? What men or gods are these? What maidens loath? What mad pursuit? What struggle to escape? What pipes and timbrels? What wild ecstasy? No direct answers were forthcoming from the speechless piece of pottery. We drew our own conclusions from the speaker's descriptions. The interrogative grammatical mood returns in stanza four with questions rendered rhetorical by being directed at an object of art. Who are these coming . . . ? To what green altar . . . Lead'st thou that heifer . . .? What little town . . . Is emptied of this folk . . .? For the first time the speaker is probing beyond the images on the urn and the images it bears. We will never know whether the sacrifice will be of propitiation or glorification since the sacrificial animal is as immortal as the human figures on the other side of the urn. Not so William Faulkner. In the conclusion of The Bear, after 16-year-old Ike McCaslin has experienced his rite of passage, Ike's father reads aloud this poem. About the last two lines, he says that Keats was "talking about truth. Truth doesn't change. Truth is one thing. It covers all things which touch the heart honor and pride and pity and justice and courage and love." Eight years after publication of The Bear, in his Nobel Address, Faulkner said that the duty and privilege of poet and writer are "to help man endure by lifting his heart, by reminding him of the courage and honor and hope and pride and compassion and pity and sacrifice which have been the glory of his past." The poet's voice "can be one of the props, the pillars to help him endure and prevail." 9818171328 by Rukhaya MK Keats' "Ode on a Grecian Urn" is a balance between the flux of human experience and the fixity of art, the contrast between enduring art and ephemeral art, and an equation between realism and aestheticism. The indefinite article in the poem refers to how Keats did not refer to any single work of Greek art; but to art in general. The origin of the poem can be traced to various sources: a marble vase in Louvre, another one in Louvre depicting a revelry scene, the famous Eligin marbles in the British museum and another one belonging to Lord Holland Keats addresses the urn as an inviolate bride and a child who is fostered by Time, the otherwise universal enemy. Keats conveys to us the great age and silent repose of the urn terming it as 'Sylvan historian', who does not relate mere factual information but projects a "creative perception into reality". The first stanza functions as an expository part and enumerates in a series of questions ideas that are to be amplified later. The second and third stanzas reveal the triumph of art over life. The lovers love without tiring and they play melodies unheard, that remain sweeter to comprehend. The beauty of maidens and the greenery of the trees shall never fade away. If the first scene depicts Dionysian revelry, the second signifies Appolonian order. It potrays the serene scene of a sacrificial ritual. If the first portrays individual yearning, the second depicts communal activity. The last Stanza brings us to the urn itself as an object: "attic shape" and "cold pastoral". The urn itself is a 'silent form' and it speaks not by means of statement but understatement. It is an enigma and will recite history to generations to come. The final statement:" Beauty is truth, Truth beauty" has come in for much criticism. Bridges has praised their artistic excellence. To T.S.Eliot, "they are a serious blemish on a otherwise beautiful poem." I.A.Richards calls it "a pseudostatement." Garrod also feels that the statement is an intrusion upon the poem. by Beth Szczepanski "Ode to a Grecian Urn," composed in 1819 by John Keats, presents a philosophy in which artistic beauty outweighs historical considerations in the appreciation and understanding of an artwork. This poem extols the virtues of the unknown; not knowing historical details allows the poet to imagine a past far sweeter than reality. As such, the artwork on the urn in question is valuable not only for its beauty, but also for its mystery. In the first stanza of this poem, Keats introduces the urn, a "Sylvan historian, who canst thus express / A flowery tale more sweetly than our rhyme." Untouched for countless years, this urn carries pictures of figures engaged in unknown activities, accompanied by unheard music. Keats wonders if the figures are men or deities, what kind of chase is underway among them, and what the music of the pictured "pipes and timbrels" might sound like. Those questions remain unanswered by the urn, a "fosterchild of silence and slow time." The second stanza of this poem describes the allure of the urn's mysterious decoration. "Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard / Are sweeter." Because we have almost no idea what ancient Greek music sounded like, we can imagine that it must have been absolutely wonderful. In the the third stanza, the poet explains how the urn's unchanging nature is a boon to its artistic value. Because the figures on the urn do not move, we can always cherish their youthful beauty. On the urn's side, one can forever savor the moment before the suitor kisses the maiden. Spring never ends in the unchanging world of the urn. The fourth stanza presents further questions about the figures on the vase. For what purpose is a garland-decorated heifer to be sacrificed? Which little town has been left perpetually empty, its citizens all away to observe the sacrificial ritual? As was the case with the lovers and musicians, the urn provides no answers to the poet's questions about the sacred ceremony. In the fifth stanza, Keats lets the urn have its say. It shall remain unchanged throughout the ages, eliciting questions like those posed in the previous stanzas, but finally proving its worth by demonstrating that those questions cannot, and indeed should not, be answered. In the end, the urn states the much-quoted line, "Beauty is truth, truth beauty'that is all / Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know." It is not, then, historical facts that make this artifact important to human life. Only its beauty truly speaks to us. The rest is unknown and unknowable. This poem reflects the anti-historical view that excessive knowledge of the historical context and original meaning of an artwork can detract from its appreciation. If we knew exactly what was happening in the pictures on the urn's surface, we would view the work too analytically to completely immerse ourselves in its mystery and beauty. As a scholar in the arts, I cannot agree with this philosophyknowledge of historical facts need not detract from our ability to appreciate the beautiful. I believe there is more to truth than beauty alone, but I do appreciate Keats' Romantic notion that the aesthetic value of the artwork speaks directly to humanity throughout the ages. Source: Keats, John. "Ode to a Grecian Urn." Reproduced at http://www.bartleby.com/126/41 .html. Analysis of "Ode on a Grecian Urn": The Title The first step in completing an analysis of "Ode on a Grecian Urn" is to read it, several times if necessary. After reading it several times, I noted the following observations on the title as part of my "Ode on a Grecian Urn" analysis: Title Analysis: The first question I have as I'm completing my "Ode on a Grecian Urn" analysis is in regards to the title. It's not an ode to a Grecian urn; it's an ode on a Grecian urn, which would indicate, at least on the surface (no pun intended), that there is an ode on the actual urn. The poem begins as an ode should, with an apostrophe, the act of speaking to someone not there or to an object, such as an urn, which means either the urn is speaking, unlikely even in a poem, or the poet is translating a picture on a Grecian urn into an ode. As I continue my analysis of "Ode on a Grecian Urn," however, it's obvious the poet is speaking to the Urn about what's on the urn; it is, therefore, both an ode on a Grecian urn and an ode to a Grecian urn. The title, I'm guessing, is "Ode on a Grecian Urn" in order to emphasize the painting on the urn and not the speaker of the poem. Read more: http://www.brighthub.com/education/homeworktips/articles/51455.aspx#ixzz0cgC27Y4T