Excerpts from John Stuart Mill, Autobiography (to be handed out and

advertisement

HIST 317: European Intellectual History: Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries

Fall 2013

MF 2-:3:20 Wyatt Hall 305

Benjamin Tromly, Department of History

Office: Wyatt 128

Email (preferred method of contacting me): btromly@pugetsound.edu

Telephone: X 3391

Office hours: Mon 10-11; W 2-4 and Fr 12-1 and by appointment (please email)

COURSE DESCRIPTION:

This course examines European intellectual history during the long nineteenth

century, a term referring to the period beginning with the French Revolution and

ending with World War One. This was an age when the continent was

transformed beyond all recognition by the “dual revolutions” of the French

Revolution and the Industrial Revolution. The course examines the different

systems of thought which Europeans generated in order to make sense out of the

tumultuous changes they experienced. We explore a wide range of themes in

European thought during the period, in the process reading texts engaging

questions of politics, culture, science, gender, sexuality, economics, urbanity and

much else. Throughout, the core theme is the attempt to find meaning and value

in a period when old mental structures—whether social, economic, cultural,

scientific, or religious in nature—seemed to be in flux. In this context, a dizzying

range of new systems of thought (“isms”) emerged, inspired adherents and

followers, but ultimately inspired intellectual challenges, leaving behind a sense

of intellectual and moral uncertainty that would characterize the twentieth

century.

The course is organized into four rough periods: 1815-1848, when the emergence

of conservatism, nationalism, and cultural romanticism marked a clear backlash

against the Enlightenment’s heritage of rationalism, materialism and

universalism; 1847-1871, an age marked by thinkers who relied on scientific and

ostensibly more “realistic” answers than the romantic age; 1871-1914, a period

when exploration of seemingly irrational, unconscious and impulsive forms of

human behavior triggered pessimism and confusion; and 1914-1930, when the

fears of an earlier age became a reality with total war and the permanent changes

it brought to Europe.

Several of the more specific goals of this course can be identified:

To expose students to modern schools of thought which continue to

inform the way we view the world

1

To develop an ability to explicate, analyze, and interpret difficult primary

sources, both orally and in writing

To gain expose to intellectual history as a sub-discipline, one which places

ideas in historical context but also requires a creative drawing of

connections between ideas in different periods and in different genres

(scholarly tracts, the novel, diaries etc.)

COURSE REQUIREMENTS:

Participation, 15%: This is a discussion-based class. You are expected to come to

class having done the readings for that day and be prepared to offer

questions and thoughts about them. Full participation in class

discussions—not merely being present—is necessary for a satisfactory

grade in the course.

Four analytical papers, 74%: You will write four analytical papers over the

course of the semester. The length requirements will expand with each

paper, as will the paper’s share of the final grade (papers 1-4 will be

weighted as follows: 12%, 17%, 20% and 25%). The first three papers will

ask you to develop original arguments based on close readings of primary

sources as well as scholarly works we will read in class. The final paper

will have you analyze a primary source in intellectual history which we

have not read and place it in the context of the course. Detailed

explanations of each assignment will be handed out in class well before

the due dates.

Paper and discussion-leading assignment, 6%: Each student will be assigned a

class date (schedule will be provided). On this day, bring a 2 page

minimum (double-spaced) paper to class that a) explores some topic of

interest to you in the readings assigned for that day and b) poses at least a

few questions to the class related to this topic of interest to you. On the

relevant class session, you will initiate our discussion of the source by

drawing on the ideas articulated in your paper and, presumably, by

drawing on the some questions you pose in your paper. You should feel

free to be creative about how you make your presentation to the class, but

the goal should be to spur a lively discussion of the topic or topics you

find important in the reading. The goal of the assignment is twofold: to

draw on your own ideas in leading our class sessions, and to give you

experience in presenting your work in a classroom setting.

Please note that you must be present in class on the appropriate date to

complete this assignment. If you absolutely must be absent for excusable

reason on that day, tell me in advance so that we can reschedule your

2

paper/presentation. Your grade for the assignment will be based on both

the paper and the presentation.

Final in-class presentations, 5%: During our final class, you will present an

answer to a question about the overall development of European

intellectual history we have studied. The goal is to reflect broadly on the

course as a whole. I will give further details toward the end of the

semester.

IMPORTANT DATES:

First Paper due, Wed. Sep 25 (Wyatt 128, 4 PM)

Second paper due Wed. Oct. 23 (Wyatt 128, 4 PM)

Third Paper due Fri. Nov 22 in class

Final paper due at start of exam period

In-class presentations on Dec. 9

OTHER COURSE INFORMATION:

•

•

•

•

Attendance at all class meetings is expected. Each unexcused absence is

viewed with irritation and dismay; after two unexcused absences, the final

grade in the course will be dropped by half a letter grade. I reserve the

right to withdraw students from the class for excessive absences (defined

as six or more unexcused absences).

If you have a physical, psychological, medical or learning disability that

may impact your course work, please contact Peggy Perno, Director of

Disability Services, 105 Howarth Hall, 253-879-3395 as soon as possible.

She will determine with you what accommodations are necessary and

appropriate. All information and documentation are confidential.

You are strongly encouraged to review UPS’s policies on academic

honesty and plagiarism as detailed in the Academic Handbook.

http://www.pugetsound.edu/student-life/student-resources/studenthandbook/academic-handbook/. Plagiarism will result in a 0 on the

assignment in question, with greater penalties possible.

All assignments must be submitted at the start of class on the due date. If

you submit a late paper, be sure to submit a hard copy to my office along

with an electronic copy. Late papers will be penalized at the rate of ½ a

letter grade per day late (a ‘B’ paper handed in two days late becomes a

‘B-‘) and will not be accepted more than five calendar days following the

due date. Please notify me before the paper is due if health or family

emergencies prevent you from submitting work.

3

•

•

•

I strongly encourage you to visit me in office hours. There is no need to

schedule an appointment during scheduled office hours. If you are

unavailable during these times, please contact me in advance by email.

The best way to reach outside of class is via email. I try to respond to

email as quickly as possible, but I cannot promise that I will respond

promptly to messages sent on weekends or holidays.

On occasion, I will send emails to the class to provide you with reading

questions and important contextual information. While the exact timing of

these emails will vary, I will send them at least a few days before the class

in question whenever possible. I encourage you to read these messages

carefully, as they will help you prepare for class and perform successfully

in the course.

GRADING CRITERIA FOR EVALUATING WRITTEN WORK:

An “A” paper contains a perceptive, original, and compelling central argument

which reflects an original perspective. It is clearly written, well-organized into

sub-arguments, and supported by a variety of specific examples drawn from the

readings.

A “B” paper is a solid effort which demonstrates a good grasp on the course

materials. But a “B” paper might have one or more shortcomings. It might

provide a summary of ideas and information drawn directly from readings and

discussions without independent thought or synthesis. Or it might give evidence

of independent thought yet suffer from unclear and/or unconvincing

presentation of an argument, a lack of textual evidence, or be sloppily written.

A “C” paper shows a decent grasp on the course material but lacks a thorough or

accurately defended argument. A paper receiving a grade lower than “C” suffers

from more serious shortcomings, such as not responding adequately to the

assignment, frequent factual errors, the lack of a cohesive thesis, poor

organization, unclear writing, or a combination of these problems.

NOTE: We will discuss paper assignments in class in advance of due dates. I am

happy to discuss writing assignments before or after you have written them.

Although I do not usually read full drafts of papers, I am happy to look at a

thesis statement or a section of a paper.

GETTING HELP WITH WRITING: Anyone can become a better writer. The UPS

Center for Writing and Learning is has a mission to help all students, at whatever

level of ability, become better writers. I strongly urge you to take advantage of

its services. To make an appointment, call 879-3404, email writing@ups.edu, or

drop by Howarth 109.

4

COURSE TEXTS:

The following titles are available for purchase at the Campus Bookstore and

through online services. They are also available on two-hour reserve at Collins

Memorial Library.

Hannu Salmi, Nineteenth-Century Europe: A Cultural History (Cambridge, UK:

Polity, 2008).

Charles Hirschfeld and Edgar E. Knoebel, The Modern World (New York:

Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1980).

Ivan Sergeevich Turgenev, Fathers and Children, trans. Michael R. Katz (New

York: W.W. Norton, 2009).

H. G. Wells, The Time Machine (New York: Dover Publications, 1995).

Sigmund Freud, Civilization and Its Discontents (New York: W.W. Norton, 1989).

Course Reader

Readings are in the course reader available for purchase from the bookstore

(listed as “CR” in the schedule of readings below). Purchasing the course reader

and lugging it to class is required. Other readings are available on moodle.

On background reading: students who feel they would benefit from reviewing

the historical context of Europe during the period in question can consult a

textbook for the period. Please contact me, as I might have stray copies of

appropriate texts in my office.

COURSE SCHEDULE:

NOTE: All reading assignments are to be completed before the class meeting for which

they are listed (for Sep 9 you are to have read Condorcet and Baker) Please bring to class

the syllabus, the assigned readings for the day, and your reading notes.

ANOTHER NOTE: The course reader materials are often not found in the same order in

the syllabus as in the table of contents of the reader. Everything marked (CR) will be in

the course reader somewhere, just scroll down the T of C to find the relevant item.

YET ANOTHER NOTE: The questions listed below under “PREP” are just that—some

questions meant to help you focus on core issues in the (sometimes dense) texts and,

thereby, to add to your confidence in discussing them. It is not advisable that you focus

on these questions for your paper and discussion-leading assignments, unless a question I

pose is one you really want to explore. Also, you should not feel that the questions I

highlight are the only important ones, of course—our discussions will be guided by your

questions as well as by mine.

F Sep. 6: Introduction to Course and Historical Context

5

Excerpt from Stefan Collini, “What is Intellectual History?”

I. The French Revolution and the age of ideologies (roughly 1789-1848)

M Sep. 9: Condorcet and the Modern Mindset

Antoine Nicolas de Condorcet, “The Progress of the Human Mind,” in The

Modern World

Keith Michael Baker, “On Condorcet’s “Sketch,’” Daedalus, 133, no. 3 (2004): 5664. (moodle)

PREP:

-We start our class with the Enlightenment, the eighteenth-century movement

which provides the immediate context for the ideas we will explore this

semester. Perhaps more than any other thinker, Condorcet embodied common

positions in Enlightenment thought: the belief in reason’s ability to solve social

and political problems, the assumption that people can be improved through

enlightenment, and the concomitant idea of progress. How does Condorcet

substantiate his picture of limitless human improvement? What is it about the

past development of the human mind that makes such a rosy picture possible?

-Baker, a foremost scholar on Condorcet, provides a highly sympathetic view of

the piece we have read. How have scholars differed in seeing the origins of the

idea of progress? Does Baker attempt to change the typical image of a selfconfident and even dogmatic Enlightenment?

F Sep. 13: The French Revolution and its Opponents: Conservatism

Peter Fritzsche, Stranded in the Present: Modern Time and the Melancholy of History,

10-32 (CR)

Edmund Burke, “Reflections on the revolution in France,” in The Modern World

OPTIONAL: Marvin Perry, An Intellectual History of Modern Europe, 204-13

PREP:

-The Fritzsche reading is a chapter from a longer study about the role of history

in European thinking in the nineteenth century. It offers an overview of the

French Revolution’s impact on mass consciousness in the period. Some questions

worth pondering include: What was new and unprecedented about the ideas of

the revolutionaries? Why did the revolution lead to a sense of “permanent moral

insecurity” (24 of F)? How did the revolution and the emergence of an

“ideological age” challenge “Enlightenment conceptions of history” (26 of F)?

-Burke is widely considered the most important conservative thinker of the

period. On what grounds does he criticize the Revolution and the Enlightenment

6

ideas that inspired it? Given the picture Fritzsche gives of the costs of the

revolution, is Burke’s a persuasive critique? Of course, progressive thinkers have

seen conservatism as reactionary, backward, and sterile. Are such critiques

applicable to Burke?

-What would be Burke’s primary objections to the Condorcet piece we read?

How might Condorcet respond to such criticisms?

M Sep. 16: Industrialism and ‘Utopian’ Socialism

Hannu Salmi, Nineteenth-Century Europe, chapters 1-2

Charles Fourier, from Theory of Social Organization (1820) and H. Saint-Simon,

Lettres d'un habitant de Genève à ses contemporains (1803) (moodle)

PREP:

-Of course, against the backdrop of the aftermath of the French Revolution and

Napoleon, another major transformation was gaining steam (clearly, no pun

intended) in industrialism. The “Industrial Revolution” was hardly an abrupt

process, and a very uneven one: most areas of Europe were still agricultural in

the first half of the nineteenth century and some countries had very little modern

industry. But the new form of production clearly had revolutionary implications

for those who experienced it. The utopian socialists (this negative

characterization came from Marx and Engels) were thinkers who sought to

suggest alternatives to the social order taking shape in Europe. As the readings

of Fourier and Saint-Simon will show, they were a diverse lot. What were the

characteristics of Fourier’s “Phalanx” as a unit of social organization? In what

ways is Saint-Simon’s view of a future society different? Indeed, are there any

similarities here? Is the classification of “utopian” useful in considering these

thinkers?

F Sep. 20: Culture of the Romantic Movement

Salmi, Nineteenth-Century Europe, chapter three

Ludwig Tieck, “The Runenberg,” in Six German Romantic Tales (CR)

PREP:

-Salmi provides an excellent overview of the emergence of the “conditions for

creative activity” (43) in the early nineteenth century. What economic, social and

cultural developments made this century an age of “worship of art”?

-How does Salmi define “Romanticism”? What trends in creative endeavors was

it directed against? What were different ways that romantic sensibilities played

out in politics in the period? Are there connections between Romantic art and

Burke’s conservatism?

7

-Tieck’s story is a classic of German Romanticism. What do you make of Tieck’s

style, insofar as it is conveyed in translation? Why does Christian eschew

gardening for the mountains? What happens to him at the Runenberg ruins?

What are the recurring symbols in the text, and what might they represent? How

does Tieck’s story reflect the core tenets of Romanticism as described by Salmi

(emotion, imagination, originality, affinity to nature, individualism etc.)

M Sep. 23: The Birth of Modern Nationalism

Hannu Salmi, Nineteenth-Century Europe, chapter four

Johann Gottlieb Fichte, “Address to the German Nation, 1807” (CR)

PREP:

-Salmi provides an excellent overview of the study of nationalism in this period.

What are some broad explanations for the rise of nationalism in this period

(Gellner on 59, Hobsbawm)? Why are intellectuals, artists, professors and other

“cultural elites” so critical to nationalism in the period? According to Salmi, what

is the relationship between nationalism and religion? Nationalism and gender

divisions?

-Fichte is a highly influential articulation of German nationalism. How does

Fichte explain what is special about Germans with relation to other nations?

What is the immediate context for Fichte’s lectures, and why do you think they

were received so well by cultural elites in Germany? Does Fichte’s vision of the

nation have any relationship to Burke’s conservatism, or the Romantic

worldview we have discussed?

First Paper due, Wed. Sep 25 (Wyatt 128)

F Sep. 27: Hegelianism and its Role in European Thought

Excerpt on Hegel from Marvin Perry, An Intellectual History of Modern Europe,

190-200 (CR)

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, “Reason in History,” from The Modern World

PREP:

-Hegel is one of the most important thinkers of the nineteenth century, although

a challenging one to read. Perry gives a great overview of Hegelianism. How did

Kantian philosophy provide the starting point for Hegel? In particular, how does

Hegel arrive at the notion of a “universal spirit” in history? How does Hegel

explain the role of the state, and how does it differ from other views of

governance, such as contract theory?

8

-Are there any fruitful comparisons to be made between Hegel and Burkean

conservatism? Does Hegel’s depiction of progress bear any resemblance to

Condorcet? How about Hegel and nationalism?

II. The Age of Science and Realism (roughly 1848-1871)

M Sep. 30: Rationalist Schemes: Utilitarianism and liberalism

Jeremy Bentham, excerpt from An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and

Legislation (1789) (moodle)

Excerpts from John Stuart Mill, Autobiography (to be handed out and placed on

moodle)

Mill, “On Liberty” (1859), in the Modern World (read the first “Introductory

section” at least)

PREP:

-Bentham, the founder of the theory of utilitarianism. How does he seek to apply

principles of Pleasure and Pain to reorganize society? Do you see any immediate

problems with this theory?

-Mill, the most influential liberal of the century, charts his attachment to

Benthamite utilitarianism (facilitated by his despotic father, a close friend of

Bentham who drilled utilitarian principles into him from early childhood) and

his disillusionment with it. How did Mill and his friends seek to change society?

What did they find appealing about utilitarianism? Does our reading of early

nineteenth century thought help to explain such an embrace of rationalistic

principles? Why does Mill come to doubt his philosophical principles and how

does he eventually overcome them? Finally, glance at the first part of “on

Liberty,” Mills’s famous articulation of liberal thought. How does Mill explain

the need for rule by the majority and individual liberty? How is the principle of

utility invoked here?

F Oct. 4: Marxism

Excerpt on Marx from Marvin Perry, An Intellectual History of Modern Europe, 254266 (CR)

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, “The Communist Manifesto,” in The Modern

World

Excerpt from Karl Marx, Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844

(moodle)

PREP:

Marxism is the most important radical ideology of the modern age, in large part

because it represents a program of political action, a way of understanding

9

society, and a theory of history and humanity. The Manifesto is the most

consolidated articulation of Marxism. Consider the following issues:

-Explain what Marx and Engels meant by the statement that "the history of all

hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles."

-According to Marx and Engels, what are the classes of capitalist society and why

do they "struggle"?

-Why do Marx and Engels say that previously the bourgeoisie had played "a most

revolutionary part" in history?

-Why do Marx and Engels call the bourgeoisie "its own grave digger"?

-According to Marx and Engels, how had industrialization "created" a proletariat,

and why was the working class a revolutionary force?

-What did Marx and Engels say was necessary to have real freedom?

-What does the Manifesto say about the nature of the "bourgeois" family, marriage,

and nationality?

For the estranged/alienated labor selection, consider the following questions:

What did Marx say was wrong with "political economy"?

-According to Marx, why is labor a commodity? Why is the product of a worker's

labor an "alien object"?

-What did Marx mean by "the relationship of the worker to production," and why

is the worker alienated by the act of production?

-According to Marx, why is the "fact" that man is alienated in the process of labor

and from labor's products both dehumanizing and socially alienating?

-According to Marx, what is the relationship of "the capitalist" to labor, and how is

this relationship connected to alienation?

M Oct. 7: Questioning the Position of Women in Europe

Salmi, Nineteenth-Century Europe, chapter five

J. S. Mill, Margaret Oliphant and the Lancet newspaper (1869) in Susan G. Bell,

and Karen M. Offen, Women, the Family, and Freedom: The Debate in Documents,

359-366, 391-405 (CR)

PREP:

-Salmi offers an evocative picture of what is customarily called the ideal of

domesticity in middle class culture of the nineteenth century. Why was the home

so important to the bourgeoisie? How was the freedom of women constricted as

a result of this focus on domestic contexts?

- The introductory section to the Bell and Offen reading is dense but very useful.

According to the authors, what was the new “authoritative language” of men

who desired to uphold patriarchal arrangements? What were different ways that

advocates for women respond to the institutional, social and cultural place of

women in bourgeois society (361)? Where did women’s rights tend to fall on the

political spectrum? Were there meaningful national differences at work?

10

-As Bell and Offen show, Mill’s text was a hugely important work in the history

of feminism. How does Mill address the question of biological differences

between men and women? According to Mill, why is female inequality

inconsistent with the spirit of modern times? What harm comes to society from

its interdiction of opportunities for women?

-Who was Margaret Oliphant? What is her major criticism of Mill’s work? Does

Oliphant have any sympathy for the cause of granting women more rights?

F Oct. 11: Turgenev, Fathers and Children (in fact, Fathers and Children)

Turgenev, Fathers and Children, chapters 1-20

PREP (for both days):

I am assigning this novel because it engages some of the ideas we have discussed

thus far: the sense of rupture in the nineteenth century, utilitarianism and the

cult of science, Romanticism, nationalism, the position of women (to name a

few). It was published in 1861, a year after the Russian Tsar Alexander II

announced the liberation of the serfs (until then, Russian peasants were almost

totally dependent and subordinate to landowners in the manner of slaves). Here

are some questions:

- Turgenev’s novel is often seen as a work of “realism,” a dominant trend in the

arts of the period that stressed positivistic and straightforward subject matter

and technique and was often geared to social criticism. How is the relationship

between master and serf depicted in the novel? Is Turgenev as author taking a

stance on serfdom or other social ills? How do the main characters relate to

Fenichka?

-Who is Bazarov and what is the meaning of his “nihilism”? How is Arkadii

different than Bazarov? How does the relationship between Arkady and Bazarov

change over the course of the novel?

- How do the fathers and sons differ in their philosophy and politics? Their

manners? Is this simply a reflection of a generation gap, or does the rift reflect a

larger crisis in Russian society? How does Bazarov relate to his parents

differently than Arkadii? Why is there a great deal of tension between Bazarov

and Arkady's uncle Pavel?

-What do the different characters think about Russia as a nation? Is this also a

matter for divergence between fathers and children?

-There are four love stories intertwined in the novel. What purpose do they serve

for the novel? Are women as a whole depicted differently than men by

Turgenev? Recall our discussion of the “woman question” – how might early

“feminists” comment on this novel?

-In chapter 13, we are given a satirical account of two “progressive” thinkers,

Mrs. Kukshin and Sitnikov, the characterization of whom is obviously satirical.

11

What is the purpose of this satire? What is the basic difference between Bazarov

and the two "emancipated” comrades?

-What do you make of the ending? Is Pisarev’s criticism on the meaning of

Bazarov and Turgenev’s agenda in depicting him a fair one?

M Oct. 14: Turgenev, Fathers and Children continued

Turgenev, Fathers and Children, remainder

Dmitrii Pisarev’s reception of novel (in Norton edition)

F Oct. 18: Urbanism and Mass Society in European Culture

Salmi, Nineteenth-Century Europe, chapter six

Charles Baudelaire, “The Painter of Modern Life” (CR)

Excerpt from Georg Simmel, “The Metropolis and Mental Life” (1903) (CR)

PREP:

-Today we examine some intellectual and cultural outcomes of the massive

expansion of cities in the nineteenth century.

-How exactly does Salmi explain how city life involved a “rearticulation of the

relation between the individual and society” (89)? Why did urban centers create

cultural trends such as Dandyism which were so shocking to societies at the

time? Where do women appear in his chapter? What opportunities, if any, did

city life offer to women?

-Salmi gives a lot of background on Baudelaire. What does Baudelaire see as the

basis for Constantine Guys’s brilliance? In what ways is this paean to an artist

similar to and different than the Romantic movement earlier in the century? How

does he define “modernity” as an accomplishment of the artist, and how does he

see artistic value in would attention to the “transitory, fugitive” element in

modern life (142 of original)?

-Written many years later, the German sociologist Simmel provides a highly

negative view of urban life, in the process turning the judgments of Baudelaire

upside down. Why is the city so detrimental to the individual in this account,

“dragging the personality downward into a feeling of its own valuelessness”

(15)? What factors might have persuaded Simmel and other Europeans to see the

city as a force for atomization and degeneracy?

Oct. 21 fall break

III. The Turn to Skepticism and Irrationalism (roughly 1871-1914)

W Oct 23: second paper due at my office, Wyatt 128, 4 PM

12

F Oct. 25: Imperialism and Racism

Salmi, Nineteenth-Century Europe, chapter eight and pp 124-8

J. A. Gobineau, Moral and Intellectual Diversity of Races (1856) (CR)

possible other short source TBD

PREP:

-The core questions for this class are how Europeans viewed racial divisions, of

which they were becoming increasingly conscious during the height of

imperialism, and how race informed notions of European identity. Salmi

provides some context on the period of imperialism and its nature as a “cultural

phenomenon” (113). How did Europeans justify and explain their dominance

over the globe? What do you make of Salmi’s discussion of Kipling and what he

sees as “contradictions” in the message of “The White Man’s Burden”? How was

imperialism connected to science?

-Gobineau, as Salmi mentions, was a French pioneer in scientific racism. How

does he classify the different races and what is the basis for his delineations?

How did race affect the behavior, traits and thinking of people? What was

produced by the “intermixture of races” according to Gobineau? What do you

make of his discussion of the lower classes in Europe, and can we connect this to

our readings on the city? How does Gobineau explain his hierarchies of races

according to beauty and strength?

M Oct. 28: Darwinism, Science and History

Roland N. Stromberg, European Intellectual History since 1789, 109-130 (CR)

Darwin excerpt from Bell and Offen, Women, the Family, and Freedom: The Debate

in Documents, 408-411 (CR)

Wells, The Time Machine, Chs. 1-4

PREP:

Questions on the Time Machine will come in due course.

F Nov. 1: Time Machine continued

Wells, The Time Machine, remainder

M Nov. 4 Rewriting Morality: Nietzsche

Roland N. Stromberg, European Intellectual History since 1789, 174-179 (CR)

Friedrich Nietzsche, “The Geneology of Morals,” from The Modern World

PREP:

13

-What does Nietzsche mean by the “slave revolt in morals” (488)?

-Why do you think Nietzsche finds the priestly moral code “brilliant” despite

what he sees as its negative consequences (485)?

-Explain the concept of “rancor.” How does it differ from the contempt of master

morality?

-What do you make of Nietzsche’s assertion there is no "doer" behind the "deed"

(494)? How does this point connect to his broader statement about transforming

values? What remains for Nietzsche if there is no subject?

-What, according to Nietzsche, is the origin of bad conscience?

-Do you see any connections here to previous thinkers we have read?

Romanticism? Utilitarianism? Racism? The nihilism of Bazarov?

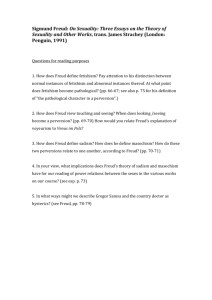

F Nov. 8: Freud, Sexuality and Women

Salmi, Nineteenth-Century Europe, 128-133

Sigmund Freud, excerpt from “On Dreams” (moodle)

Hannah S. Decker, “Freud's Dora case” in Michael S. Roth, Freud: Conflict and

Culture (CR)

PREP:

-How does Salmi explain the mood of pessimism and insecurity at the turn of the

century? What created the fear of barbarism and a decline of civilization?

-I might offer some questions on the Dreams prior to class.

-On “Dora.” Where did Freud get his patient wrong? Why did he make these

lapses? Were his harmful actions toward Dora mere miscalculations or did they

reflect fundamental flaws in his mode of psychoanalysis? What does Decker

think about this issue?

M Nov. 11: Fin de siècle Culture

Salmi, Nineteenth-Century Europe, 133-139 and “Things to come”

Franz Kafka, “The Metamorphosis” (1915) (CR)

F Nov. 15 Irrationality in Politics

A. James Gregor, Marxism, Fascism, and Totalitarianism: Chapters in the Intellectual

History of Radicalism, chapter four (CR)

Georges Sorel, “Reflections on Violence” (CR)

Le Bon, The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind (CR)

PREP:

14

-On Sorel: What does Gregor have to say about the state of Marxism at the turn

of the century? Why did different Marxist interpretations of current realities and

schools of thought emerge? What was syndicalism?

-How did Sorel break with doctrinaire Marxism (pp 84-6)? What intellectual

influences did Sorel draw on to argue against a strictly materialist view of

history? What dangers did he see in contemporary currents of Marxism (see 8991)?

-How did Sorel explain the need for the myth of the general strike?

-Le Bon was on the right of the political spectrum (it is said that Mussolini read

The Crowd tens of times). How does he explain how crowds affect human

behavior? Was there any alternative to allowing crowds to hijack civilization?

Who did understand crowds? Why might such an analysis have resonated at the

time?

-For both thinkers: Do you see any connections to Nietzsche, Freud and Kafka or

other thinkers here?

World War One and the Search for New Answers

M Nov. 18 Responses to war and revolution: Left

Stanley Payne, A History of Fascism, chapter 3 (CR)

Lenin, “State and Revolution” excerpt ONLY, in The Modern World

Excerpt from Ignacio Silone in The God Who Failed (CR) read at least 76-82 and 99114 (of original pagination)

PREP: questions to come on Lenin.

-Silone: Why do you think so many of the communists he described were willing

to risk and sometimes to lose their lives in the period? What was it about

communism that encouraged such self-sacrifice?

-Silone provides a rich discussion of the Comintern, the Third Communist

International founded by the Bolsheviks which contained the different

communist parties of the period. How did the Russian communists and Stalin

approach this organization and the other communist parties? Why exactly did

Silone earn the wrath of the Comintern leaders and fellow communists? How

was it possible for communists to be as cynical as Silone describes?

F Nov. 22 Film and European culture (and paper due!)

Salmi, Nineteenth-Century Europe, chapter 7

Paper three due in class

M Nov. 25: Responses to war and revolution: Right

15

Alfredo Rocco, “The Political Doctrine of Fascism” (1925) (CR)

At least a few pages of Adolf Hitler, “Mein Kampf,” from The Modern World

PREP: What is Rocco’s criticism of the previous few centuries of European

political thought? Do you find any flaws in his account?

-How does Rocco explain why fascism’s critics are so dismissive of it as an

intellectual system?

-What are the core values that fascism proposes in place of the “atomistic,

materialist” schools it opposes?

-Where would you situate Italian fascism in the history of Western thought we

have examined? What are its influences? How does Hitler’s worldview differ

from Rocco?

Nov. 27-29 Thanksgiving

Dec. 2 Freud, Civilization and Its Discontents

~Freud, Civilization and Its Discontents, chs. 1-4

PREP (both classes);

- Chapter 1: How, according to Freud, do we come to realize that there are things

outside of our selves (or ego)?

-How does he use this idea to explain the "feelings" of religion?

-What is the point of Freud's discussion of the archeology of Rome?

Chapter 2: What does Freud mean when he says that ordinary people's

understanding of religion is "infantile"?

-What does Freud mean by "the pleasure-principle"? How does this relate to the

idea of "happiness"?

-What does he mean by "libido-displacement" and what does this have to do with

the pleasure principle? What does this have to do with art and culture? Religion?

Love?

-What is Freud's main point in this chapter?

Chapter 3: What does Freud consider the three sources of human suffering?

-Why does Freud say that civilization has been a cause of human misery? Why is

modern man hostile to civilization?

-What does Freud mean by culture? What does he consider achievements of

culture and why?

-Why does civilization also require beauty, cleanliness, and order?

-How does Freud link the idea of libidinal sublimation {displacement-see above} to

civilized activities?

Chapter 4: Describe the "primitive family." Why was it not civilized?

How does Freud explain the evolution of the first laws (totems)?

16

How does Freud use the need for physical love (eroticism) to explain the

emergence of culture?

How does "inhibited" love (friendliness) bind society together?

Why is there a rift (a contradiction) between love and culture? The family and

society?

Dec. 6 Freud, Civilization and Its Discontents continued

~Freud, Civilization and Its Discontents, remainder

PREP:

Chapter 5: How does Freud explain the conflict between sexuality and civilization?

-Why does Freud have difficulty with the proposition "Thou shalt love thy

neighbor as thyself"?

-Why are we inclined towards aggression, and how does this require us to be

cultured?

What does Freud mean by saying that "Civilized society is perpetually menaced

with disintegration through this primary hostility of men towards one another"?

Chapter 6: How does Freud use the idea that hunger and love are the fundamental

motivations of humans to derive the idea of a "death instinct"?

-How does Freud derive from the idea of a death instinct the idea that a tendency

towards aggression is innate and instinctual?

-How does this chapter help Freud explain "the riddle" of the evolution of culture?

Chapter 7: How does Freud define "guilt," and where does guilt come from?

-Why does he say that "bad conscience" is the dread of loosing love?

-What does he mean by super-ego, and how and why does it create guilt? What

about the dread of authority?

-What does Freud mean by saying that man's guilt goes back to the murder of the

father?

-Why does Freud consider it a necessary conclusion that civilization brings the

intensification of the felling of guilt?

Chapter 8:

-Why does Freud consider the sense of guilt the most important problem in the

evolution of culture? What is the price of progress? Why?

-Why, according to this chapter, has civilization led to greater aggression?

Finally, think also about Civilization and its Discontents in the context of the other

thinkers we have read this semester. Are these ideas rooted in the Enlightenment,

Romanticism or both? Are there any similarities to Marx, Darwin or Wells, or

Nietzsche? In what ways does this work reflect its date of publication (1930)?

Dec. 9 In-class presentations

17

Note: this syllabus is subject to change as needed for the successful outcome

of the course.

Paper and discussion-leading assignment dates

M Oct. 7 Doyle,Emily Clare

F Oct. 11: Egan,Samuel Cameron

M Oct. 14: Garner,Nate E

M Oct. 28: Greenfield,Scott M

F Nov. 1: Hayman,Alexander Kai-Tian

M Nov. 4: Hopewell,Natalie Taylor

F Nov. 8: Morse,Quentin Hayward

M Nov. 11: Rathje,William John

F Nov. 15: Samuelson,Alexandra Rae

M Nov. 25: Stewart,Charles Prescott

Dec. 2: Taquin,Julie Margueritte

Dec. 6: Temple,Robin Sharlene

18