a Word Version

advertisement

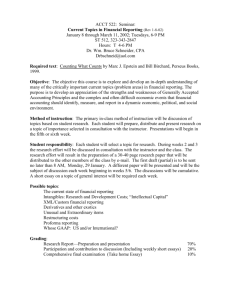

University Writing Program Fall 2005 Donald Meisenheimer, CAI Coordinator dkmeisenheimer@ucdavis.edu Peer Review on the Overhead Screen Summary Each student writes a rough draft of a five-page paper. (In the class I observed, the paper was devoted to the “Application of Technical Terms and Analysis,” using Mary Louise Pratt’s transcribed lecture, “Arts of the Contact Zone.” This exercise could be done with any essay, however.) In groups of three, students exchange their drafts by email, forwarding one copy to the instructor. Students read the drafts and email letters to each author (and the instructor) criticizing the papers. In class, the instructor reviews the prompt for the assignment, then notes common errors or problems he saw in the drafts. Next, he chooses one student willing to read her draft aloud as the class follows along. The two students who emailed her their criticisms of the draft present those criticisms to the class, and a discussion of the draft’s merits follows. The instructor wraps up the discussion with a few of his own suggestions for improving the paper. Target Courses I observed this lesson in a UWP 101 Advanced Composition course, although it has wide application in other UWP courses. Amount of Time Required The lesson took about 35 minutes for a single 5-page paper and two presented critiques. There was time, therefore, for a second student’s paper to be presented and critiqued. Software You’ll Use Word, Remote Desktop, and the Classroom Pickup Folder. Prep Before class, the instructor should place the two assignment prompts, “Application of Technical Terms and Analysis,” and “Workshop Goals and Logistics” in the classroom pickup folder. Then he should skim over the rough drafts he has received from the students (both the papers and their critique letters) and note common problems. He should also identify a volunteer beforehand who is willing to read her paper aloud to the class and let her group criticize her aloud from their letters. LESSON PLAN Background Each student writes a rough draft of a five-page paper on the “Application of Technical Terms and Analysis.” In groups of three, students exchange their drafts by email, forwarding one copy to the instructor. Students read the drafts and email letters to each author criticizing the papers, using as a guideline “Workshop Goals and Logistics.” Step 1: The Instructor Reviews the Prompts for the Assignments After pulling down the overhead screen and turning on the projector, the instructor drags the assignment prompt for “Application of Technical Terms and Analysis” to the desktop and opens it for the class to see. He reads the prompt aloud. Then, in a blank Word document on screen, he types some of the common problems he’s seen in the rough drafts emailed to him. In the class I observed, the instructor noted two typical approaches to the prompt in terms of the papers’ overall structures. He discussed the merits of each approach, suggesting that one might require more work in order to develop an argument, while the other might allow students to dig deeper. Students then asked a few questions about the invididual approaches they took. Next, the instructor addressed the scope of the thesis statements he reviewed. Again, he noted two general approaches that kept appearing over and over, focusing on a less effective type of thesis that was merely descriptive. He pointed out that the assignment asks for analysis as well. Before moving on to the presentation, the instructor next reviews the prompt for the letters students sent to each other critiquing their drafts. He drags the assignment prompt “Workshop Goals and Logistics” from the pickup folder to the desktop, opens it, and reads it. He can use this opportunity to point out inadequacies in the letters of critique circulated by the students so far (some of them being too short, for example). Step 2: A Student Reads Her Paper Aloud Now that the instructor has reviewed the assignment prompts and talked about ineffective aspects of students responses to the assignment so far, he moves on to the main part of the class: a presentation of a student’s paper. He says: “We’ll look at some essays now and, and as we examine these two rough drafts and peer reviews, let’s pay particularly close attention to the structure of the arguments and the scope of their thesis statements, making sure that the thesis is more than just descriptive.” Using Remote Desktop, the instructor selects and observes his volunteer student’s rough draft (open on her own computer). He asks that the rest of the class follow along on the overhead screen as she reads her essay aloud, jotting down comments with a pen or opening a Word document on their computers and typing notes. Tip: As the volunteer reads aloud, students might want to follow along on their own computers (rather than reading from the overhead screen). The instructor might use the share command in Remote Desktop, placing the student’s draft on everyone’s screen. Step 3: Two Students Present Their Criticism of the Paper After the volunteer student has finished reading her paper aloud, the instructor suggests she use the comment function in Word to enter comments into her draft as she hears them from other students. Alternatively, she could type out the comments in a Word document. The instructor says: “Now let’s have the two people who critiqued her paper present their criticisms.” The students referred to the letters of critique they emailed the volunteer. In the class I observed, the first student spoke to the class in very general terms, and referred to a few grammatical errors. The second student more adeptly zoomed in on one of the two issues the instructor had brought up: argument structure. She identified which structural approach the volunteer had taken, and argued that it worked fine. Other students weren’t so convinced, and they began to chime in with their own commentary on the paper, noting what they liked and did not like. The instructor prompted them to consider the analytical scope of the thesis (one of the two main areas he addressed earlier in reviewing the assignment prompts). First, he asked students to identify the thesis. He highlighted the thesis on the overhead screen once they did. Students suggested that it was vague, or merely descriptive. The instructor solicited further input in order to pin down the specific weak points, and suggested there might be specifics mentioned in the paper itself which could be plugged in here. Step 4: The Instructor Adds a Few Final Comments on the Paper Now that the critique are finished in the class has discussed the presented draft, the instructor can end by reading aloud his overall criticisms of the volunteered student number paper, reaffirming at least one other student’s criticism or praise. Essay #2: Application of Technical Terms and Analysis Due Dates: Rough Draft: Final Draft: 5 page min. Assignment: Using Mary Louise Pratt’s transcribed lecture, “Arts of the Contact Zone,” carefully compile definitions of the following terms: contact zones, autoethnographic texts, transculturation, imagined communities (both Anderson’s definition as Pratt presents it as well as her revised version that critiques it), and safe houses. Apply these various definitions where appropriate to one or more of the essays we’ve read. Anzaldua, Rodriguez, Freire, and Baldwin are all writers whose essays can be read according to the terms Pratt generates. Write an essay that applies these terms to the text you’ve selected as well as to some experience in your own life. As we do not all have the same diversity of experience that Pratt’s terminology would seem to apply to, I suggest you use the term “culture” rather loosely. It does not have to apply only to national/ethnic/racial cultures. The term culture and the idea of “contact zones” between them could also apply to geographic cultures (small town vs. big city), gendered cultures (male & female), social cultures (fraternities, political clubs, religious organizations, etc), or any kind of group affiliation to which you might belong. I suggest that you write this essay in at least 4 steps. 1) Write a précis of “Arts of the Contact Zone” where you trace not only the trajectory of Pratt’s argument but also carefully note the definitions of the terms she employs. 2) Write an analysis of one of the other texts using Pratt’s language. For example, you might consider the ways in which the experiences and language that James Baldwin uses might be reframed according to Pratt’s terminology. 3) Write about your own experience in a “contact zone.” 4) Synthesize parts one, two, and three into a coherent essay whose argument evaluates the utility of Pratt’s language. Draft Workshops Assumptions: The most successful writing is a product of revision. Even the student writer who can generate an “A”-level paper the night before the paper is due can improve her writing through the process of revision. In fact, one’s writing cannot develop beyond a certain point unless the writer identifies writing as a craft, a series of choices, a process. Furthermore, as writers we are so familiar with our writing that often we cannot see where that writing fails to make sense to the reader. Yet because your peers cannot read your mind, they are able to identify aspects of your writing that could be improved. Thus, workshops are a useful forum in which we can get feedback about our written work. Goals: To act as constructive critical readers of one another’s essays in order to improve the writing we generate in this course have the opportunity to read, critique, and thus learn from others’ writing styles and strategies be introduced to new perspectives begin acting as careful readers of writing in order to learn how to become more critical readers and editors of our own writing Logistics: 1. 2. 3. 4. Email the copy of the rough draft to each member in your group Read through each other’s rough drafts while making comments in Word. Formulate responses in your comments to the four questions below. Write up a peer response letter and email a copy to the writer and one to me. Comments in Word: Using the comment function in Word, annotate the rough draft. You should not focus too much of your energy looking for and correcting grammatical, mechanical, or stylistic problems. Try and pay more attention to the larger issues such as the quality of the thesis statement, the overall structure and organization of the essay’s argument, etc... Questions: 1. How does the essay present a clear thesis that 1) presents a clear paraphrase of Freire and Rodriguez’s arguments? 2) Clearly articulates the writer’s own experience with regards to the two different models of education. 2. How does the essay structure its argument? Do the opening and middle parts of the essay satisfactorily set up the argument? Does the writer assume absolute difference between the two positions presented by Freire and Rodriguez? 3. Analyze one of the body paragraphs of the essay. Does it have a topic sentence? Are there transitions between the sentences and ideas? 4. Does the essay have an effective conclusion that sums up the argument as well as the evidence presented throughout the paper? Does the essay’s conclusion provide a better form of the argument than the introduction? If so, should the essay be revised to begin where the conclusion ends? Peer Response Letter: The main goal of the peer response letter is to offer answers, in a more formal way, to the workshop questions above. Think of the peer response letter as a resource for the writer when he/she goes home after the workshop and begins the revision process. The response letter also provides an opportunity for you to think through your response to the essay and to record your ideas so as to be a more prepared and reliable workshop participant. The letter must be one full page typewritten. It may accompany marginal comments written on the draft itself or may stand alone. You may design this document as you see fit. All told, however, it is a good idea to write the kind of response that you would like to receive. Usually this means that the letter should be substantial, constructively critical, and clear. Some tips for offering feedback: Start out your response by pointing out something you think the writer did well. It is just as important to let the writer know what works as what doesn’t work. Often we are just as unable to discern what works in our writing as what does not. Try to phrase your criticism as questions, or in terms of your own perspective. It is important to recognize that there is never one way to revise an essay, and what one reader thinks is a sophisticated argument might seem, to another reader, ill-formulated and overly general. You can acknowledge that judging writing has a subjective aspect (and that letting others read and comment on one’s writing can be a distressing, insecurity-filled experience), by framing your comments as if you are in conversation with the writer rather than speaking as the Final Authority on good writing. For example: Instead of writing “What!?” in the margin of the draft, or writing “This topic sentence is not effective.” Try writing something like “I find this point confusing, particularly the part about Rodriguez’s mother. I think you need to explain what you mean more clearly,” or “How might you make this topic sentence more specific?” Also keep in mind that the more specific your commentary is, the more valuable it will be to the writer. Peer Response Letter Grading: The peer response letters will be graded on a 5-point scale. The writer who receives the letter will be responsible for assigning the letter additional points based on its substance, helpfulness, and clarity. (5 points for an excellent response that exceeds expectations, 4 points for a very good response that offers well thought out, specific advice and is easy to understand, 3 points for a good response that offers some good feedback but may also include overly general or unclear advice, 2 points for a fair response that seems partially thought out or not useful, and 0-1 points for a substandard response that merely completes the assignment without offering useful, substantive feedback). The essay writers will also be asked to include, in the cover letter to the final draft, a summary of the feedback he/she found to be most helpful in the revision process and an acknowledgment of who provided that feedback. Most of those useful comments come from the peer response letters. Common Concerns About Workshops: Many times, before or during workshops, students have come to me and expressed a common concern: “But I am not a good writer. How can I be expected to give valuable feedback to my fellow students?” Some critics claim that workshops are a waste of time, a case of “the blind leading the blind.” It is true that as the quarter progresses you will learn more about writing and, I assume, will therefore become more skilled at responding constructively to others’ writing. Yet as an intelligent reader you have a lot to offer the writer whose essay you are responding to. Remember that in workshops it is not our responsibility to tell the writer how to fix his draft. On the contrary, we are to let the writer know what parts of the essay are confusing, clear, too general, or effectively written. In other words, we serve as a trial audience for the writer; often we see things in the writing that the writer cannot see. That insight, alone, provides valuable feedback to the writer and gives him a good place to start the revision process. Finally, many students (especially after the first workshop) express frustration that people in their workshop groups were “too nice.” This concern draws our attention to a central challenge of workshopping: it is very difficult to give critical feedback to anyone let alone people you have barely met. At the same time, making constructively critical comments and being nice are not mutually exclusive. If we all approach the challenge of workshopping determined to seriously and respectfully consider one another’s work and willing to offer the kind of feedback that we would like to receive, we can all improve our writing without hurting one another’s feelings or being inappropriately discouraging.