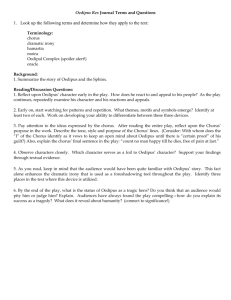

Oedipus Rex

Study Questions for Oedipus the King

Name_____________________________________________________ Period_________

Part I (p. 469-499)

1.

How does Oedipus respond to the priest’s pleas for help with the suffering of Thebes?

2.

Knowing as you do Oedipus’ true family background, find and record one line or sentence that demonstrates dramatic irony—where Oedipus doesn’t understand the full meaning of his words, but we do.

3.

At his entrance, how is Teiresias described by the Chorus? What audience attitude should this description establish?

4.

Why does Teiresias at first refuse to tell Oedipus the truth?

5.

How does Oedipus react when Teiresias reveals to him the truth? Whom does Oedipus assume is behind Teiresias’s claims? Why?

6.

When the Chorus intercedes in the argument of Oedipus and Teiresias, of what does he remind

Oedipus?

7.

What character trait of Oedipus is revealed by the fact that Oedipus accuses Creon of treason without first hearing his side?

8.

What rational argument does Creon use to convince Oedipus that he has no designs on the throne of Thebes?

Page 1 of 6

Study Questions for Oedipus the King

9.

What advice does the Chorus give Oedipus in the middle of this argument?

10.

Why does Oedipus release Creon?

11.

What is prophetic about Creon’s remark that “Natures like yours are justly heaviest for themselves to bear” (752-753).

12.

What proof does Jocasta offer to support her opinion that one shouldn’t believe in prophecies?

13.

What detail from Jocasta’s story of Laius’ murder pricks Oedipus’ memory?

14.

What is revealed about Oedipus’ personality by his description of the encounter he had with the old man where the three roads meet?

15.

Of what particular sin does the Chorus warn? How is this connected to religion?

16.

What worry does the chorus express just before Jocasta enters (end of Part I)?

Page 2 of 6

Study Questions for Oedipus the King

Part II (pages 503-524)

17.

What is ironic in the opening of part II, where Jocasta burns incense to the gods (recalling the opinions she stated earlier)?

18.

What message does the messenger from Corinth bring?

19.

What attitude toward the gods does Oedipus exhibit after learning of Polybos’ death? Why does this cause us to worry?

20.

Though Oedipus is comforted that Polybos, his father, has died of natural causes, what aspect of the oracle still troubles Oedipus?

21.

How does the messenger prove that Oedipus was not the child of Polybos and Merope?

22.

Why does Jocasta so insistently attempt to stop Oedipus’ questioning of the messenger?

23.

Who attests to the trustworthiness of the long awaited shepherd?

24.

What might we consider the climax of the play?

25.

What does the Chorus think of Oedipus now?

26.

What news do we learn about Jocasta? What does Oedipus do to himself? Why?

Page 3 of 6

Study Questions for Oedipus the King

27.

Who is to rule Thebes now that Oedipus is exiled? Why is this ironic?

28.

What requests does Oedipus make of Creon?

29.

What future does Oedipus predict for his daughters? Do you think he is right? Why should we take him seriously now?

30.

How does Creon exert his authority at the end of the play?

31.

What parting caveat (warning or caution) does the chorus issue as they depart?

32.

Hamartia is the mistake or error committed by a tragic character which in part accounts for his misfortunes. What is Oedipus’ hamartia?

33.

Identify how the Oedipus play follows the dramatic structure of: a.

Exposition b.

conflict c.

rising action d.

climax e.

falling action f.

resolution

Page 4 of 6

Study Questions for Oedipus the King

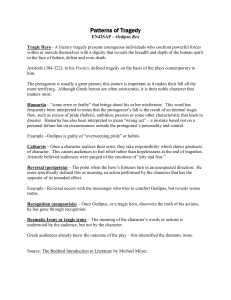

Terms to know for Oedipus the King unit

1. Hamartia (Ancient Greek: ἁ μαρτία) is a term developed by Aristotle in his work

Poetics . The term can simply be seen as a character’s flaw or error. The word hamartia is rooted in the notion of missing the mark (hamartanein) and covers a broad spectrum that includes accident and mistake, as well as wrongdoing, error, or sin. In Nicomachean Ethics , hamartia is described by Aristotle as one of the three kinds of injuries that a person can commit against another person. Hamartia is an injury committed in ignorance (when the person affected or the results are not what the agent supposed they were).

This form of drawing emotion from the audience is a staple of the Greek tragedies. In Greek tragedy, stories that contain a character with a hamartia often follow a similar blueprint. The hamartia, as stated, is seen as an error in judgment or unwitting mistake is applied to the actions of the hero. For example, the hero might attempt to achieve a certain objective X; by making an error in judgment, however, the hero instead achieves the opposite of X, with disastrous consequences.

2. Hubris is a term used to indicate overweening pride, self-confidence, superciliousness, or arrogance, often resulting in fatal retribution. In ancient Greece, hubris referred to actions which, intentionally or not, shamed and humiliated the victim, and frequently the perpetrator as well. The word was also used to describe actions of those who challenged the gods or their laws, especially in Greek tragedy, resulting in the protagonist's downfall.

3. Catharsis (Ancient Greek: Κάθαρσις) is a Greek word meaning "purification", "cleansing" or

"clarification." The term in drama refers to a sudden emotional climax that evokes overwhelming feelings of great sorrow, pity, laughter or any other extreme change in emotion, resulting in restoration, renewal and revitalization in members of the audience.

Using the term "catharsis" to refer to a form of emotional cleansing was first done by the Greek philosopher Aristotle in his work Poetics . It refers to the sensation, or literary effect, that would ideally overcome an audience upon finishing watching a tragedy (a release of pent-up emotion or energy).

4. Peripeteia (Greek, Περιπέτεια) is a reversal of circumstances, or turning point. The term is primarily used with reference to works of literature. Peripeteia is a sudden reversal dependent on intellect and logic.

In Sophocles' Oedipus Rex, the peripeteia occurs towards the end of the play when the Messenger brings Oedipus news of his parentage. In the play, Oedipus is fated to murder his father and marry his mother. His parents, Laius and Jocasta, try to forestall the oracle by sending their son away to be killed, but he is actually raised by Polybus, king of Corinth, and his wife Merope. The irony of the

Messenger’s information is that it was supposed to comfort Oedipus and assure him that he was the son of Polybus. Unfortunately for Oedipus, the Messenger says, “ Polybus was nothing to you,

[Oedipus] that’s why, not in blood” (Sophocles 1113). The Messenger received Oedipus from one of

Laius’ servants and then gave him to Polybus. The plot comes together when Oedipus realizes that he is the son and murderer of Laius as well as the son and husband of Jocasta.

Page 5 of 6

Study Questions for Oedipus the King

5. Tragedy (Ancient Greek: τραγ ῳ δία, tragōidia , "goat-song") is a form of art based on human suffering that offers its audience pleasure. The philosopher Aristotle said in his work Poetics that tragedy is characterized by seriousness and dignity and involving a great person who experiences a reversal of fortune

( Peripeteia ). Aristotle's definition can include a change of fortune from bad to good as in the Eumenides , but he says that the change from good to bad as in Oedipus Rex is preferable because this effects pity and fear within the spectators. Tragedy results in a catharsis (emotional cleansing) or healing for the audience through their experience of these emotions in response to the suffering of the characters in the drama.

According to Aristotle, "the structure of the best tragedy should be not simple but complex and one that represents incidents arousing fear and pity--for that is peculiar to this form of art." This reversal of fortune must be caused by the tragic hero's hamartia , which is often mistranslated as a character flaw, but is more correctly translated as a mistake. According to Aristotle, "The change to bad fortune which he undergoes is not due to any moral defect or flaw, but a mistake of some kind." The reversal is the inevitable but unforeseen result of some action taken by the hero. It is also a misconception that this reversal can be brought about by a higher power (e.g. the law, the gods, fate, or society), but if a character’s downfall is brought about by an external cause, Aristotle describes this as a misadventure and not a tragedy.

In addition, the tragic hero may achieve some revelation or recognition (anagnorisis--"knowing again" or

"knowing back" or "knowing throughout") about human fate, destiny, and the will of the gods. Aristotle terms this sort of recognition "a change from ignorance to awareness of a bond of love or hate."

In Poetics , Aristotle gave the following definition in ancient Greek of the word "tragedy" which means

Tragedy is an imitation of an action that is admirable, complete (composed of an introduction, a middle part and an ending), and possesses magnitude; in language made pleasurable, each of its species separated in different parts; performed by actors, not through narration; effecting through pity and fear the purification of such emotions.

6.

Paradox as a literary device has been defined as an anomalous juxtaposition of incongruous ideas for the sake of striking exposition or unexpected insight. It functions as a method of literary analysis which involves examining apparently contradictory statements and drawing conclusions either to reconcile them or to explain their presence.

(Tieresius is blind but he is a “seer”, Oedipus can see, but he is blind to his situation).

7. Irony (from the Ancient Greek ε ἰ ρωνεία eirōneía

, meaning hypocrisy, deception, or feigned ignorance) is a literary or rhetorical device, in which there is an incongruity or discordance between what one says or does and what one means or what is generally understood.

Dramatic irony is the device of giving the spectator an item of information that at least one of the characters in the narrative is unaware of (at least consciously), thus placing the spectator a step ahead of at least one of the characters.

Situational irony describes a discrepancy between the expected result and actual results when enlivened by 'perverse appropriateness. For example: When John Hinckley attempted to assassinate President Ronald

Reagan, all of his shots initially missed the President; however a bullet ricocheted off the bullet-proof windows of the Presidential limousine and struck Reagan in the chest. Thus, the windows made to protect the President from gunfire were partially responsible for his being shot.

Verbal irony is distinguished from situational irony and dramatic irony in that it is produced intentionally by speakers. Examples of ironic similes are “funny as cancer”, “clear as mud”. It is similar to sarcasm.

Page 6 of 6