An Introduction to Authentic Learning

advertisement

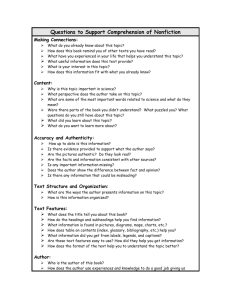

An Introduction to Authentic Learning “Authenticity consists in having a true and lucid consciousness of the situation, in assuming the responsibilities and risks that it involves in accepting it in pride or humiliation, sometimes in horror or hate.” (Sartre, 1965: 90) The Theory of Authentic Pedagogy Authentic pedagogy is based on the premise that students’ work should prepare them for the intellectual work that their various roles in society will demand of them and involves “intellectual accomplishments that are worthwhile, significant and meaningful” (Newmann, 1996: 23). This theory has been extended into the development of three criteria for authentic intellectual achievement (Newmann, 1996): 1. Student construction of knowledge ie.students need to construct their knowledge, building on what they already know (as in constructivist theory). Students are thus involved in organising, interpreting, evaluating, or synthesising prior knowledge to solve new problems. Instruction focuses on the development of concepts and deep understanding through cognitive development or knowledgebuilding, rather than developing behaviours or skills (Fosnot, 1996). Learning is thus an active process, with teaching providing a means of facilitating active student mental processing (Gagne, 1985). 2. Discipline inquiry - involves use of a prior knowledge base, in-depth understanding, and elaborated communication. Students acquire a necessary base of facts, vocabularies, concepts and theories, however the power of this knowledge lies in its use by students to gain a deeper understanding of specific problems. They use complex forms of communication both to conduct their work and present their ideas. 3. Value beyond the classroom ie. to “have meaning or value apart from documenting the competence of the learner” (Newman, Secada, & Wehlage, 1995 p.11). Learning activities may include integrating students' experiences outside the classroom into the curriculum, or involving students in new activities beyond their educational environment. The concept of value beyond the classroom involves transferring/applying knowledge to an area that: has personal significance for the students; has relevance to the ‘real world’; has value to society. 1 Newmann and Associates (cited in Elmore & Rothman, 1999: 75) restructured these three criteria into four standards associated with authentic pedagogy: Higher-Order Thinking - students are involved in manipulating information and ideas by synthesising, generalising, explaining, hypothesising, or arriving at conclusions that produce new meaning and understandings for them. Deep Knowledge – students consider the central idea of a topic or discipline with enough thoroughness to explain connections and relations and to produce relatively complex understandings. Substantive Conversation - students engage in extended conversational exchanges with the tutor or their peers about subject matter in a way that builds an improved and shared understanding of ideas or topics. Connections to the World Beyond the Classroom - Students make connections between substantive knowledge and either public problems or personal experiences. These four standards provide a useful template for focusing consideration of the curriculum and its assessment. The Practice of Authentic Pedagogy The term “authentic learning” is generally used to refer to the discussion, exploration and tackling of real-world problems and projects. Core elements of authentic learning are that it should: be learner-centred; involve active learning; use authentic tasks. Authentic tasks: have real-world relevance; are ill-defined, requiring students to define tasks and sub-tasks to complete the activity; comprise complex tasks to be investigated over an extended period of time; provide the opportunity to examine the task from alternative perspectives, using a variety of resources; provide the opportunity for collaboration; provide the opportunity to reflect; can be integrated and applied across different subject areas and beyond domainspecific outcomes; are seamlessly integrated with assessment; allow for competing solutions and diversity of outcomes. Within our teaching we are aiming to ensure that students not only know the content of the discipline when they graduate, but are able to use the acquired knowledge and skills in the real world. To achieve this, assessment must inform us whether students can apply what they have learned in authentic situations. For example, if we want to know if our students can interpret literature, test a hypothesis, develop a business plan, converse in a foreign language, or apply other knowledge and skills they have learned, then authentic assessments will provide the most direct evidence. 2 Authentic learning is a pedagogical approach that allows students to explore, discuss, and meaningfully construct concepts and relationships in contexts that involve real-world problems and projects that are relevant to the learner (Donovan, Bransford, & Pellegrino, 1999). For learning to be authentic, students should be engaged in genuine learning problems that foster the opportunity for them to make direct connections between the new material that is being learned and their prior knowledge. These kinds of experiences have the potential to increase student motivation. In the process of supporting students’ learning, we recognise that they bring with them experiences, knowledge, beliefs, values and curiosities. Authentic learning provides a means of bridging those elements with ‘classroom learning’. The literature suggests that authentic learning has several key characteristics. Learning is centred on authentic tasks that are of interest to the learners. Students are engaged in exploration and inquiry. Learning, most often, is interdisciplinary. Learning is closely connected to the world beyond the ‘classroom’. Students become engaged in complex tasks and higher-order thinking skills, such as analysing, synthesising, designing, manipulating and evaluating information. Students produce a product that can be shared with an audience outside the ‘classroom’. Learning is student-driven with tutors, student peers, friends, family and outside experts all assisting/coaching in the learning process. Learners employ scaffolding techniques. Students have opportunities for social discourse. (Cronin, 1993; Donovan et al., 1999; Newman & Associates, 1996; Newmann et al., 1995; Nolan & Francis, 1992). Assessment associated with “authentic learning” encourages the integration of teaching, learning and assessing. Rather than administering a ‘test’ after knowledge or skills have (hopefully) been acquired, the authentic learning model uses the same authentic task as a learning vehicle and as a means to measure the students' ability to apply the knowledge or skills. For example, when presented with a real-world problem to solve, students learn in the process of developing a solution, tutors facilitate the process, and the students' solutions to the problem become an assessment of how well the students can meaningfully apply the concepts. This can facilitate an integrative approach to assessment (promoting the use of formative assessment), yet reducing the potential for over assessment. Authentic assessment is an approach in which learning objectives are assessed in the most direct, relevant means possible. As such, authentic assessments are criterion-referenced measures designed to promote the integration of factual knowledge, higher-order understanding and relevant skills. Authentic assessments are often based on performance, requiring students to use their knowledge in a meaningful context. In authentic assessment, performance expectations guide learning activities and are made clear to students prior to instruction. Generally, authentic assessment is an ongoing process involving both self and external evaluation as well as the gradual compilation of material into an holistic product. While there are differences between traditional and authentic assessment, it is important to remember that traditional and authentic assessments are complementary models; both types of assessment are important to producing wellrounded, informed students. 3 Within H.E., what are we assessing? Possibly one of the most distinctive features of H.E. learning is that of higher order thinking skills (Heywood 2000, chapter 2). For example, Ramsden (1992, chapter 3) includes independent judgement and critical self awareness within the aims of H.E. Methods of assessment can contribute to, or hinder, the achievement of such stated aims, in a process known as ‘assessment backwash’ (Biggs, 1999, chapter 8), in which the curriculum is defined by the assessment for students (Ramsden, 1992, 187). All assessment has the potential to support, or undermine, the achievement of planned learning outcomes. In the case of independent judgement and critical self awareness, the use of peer and self assessment may provide examples of authentic assessment. Peer assessment (Stefani, 1994; Zariski, 1996) involves students in the use of discipline knowledge and skills and the application of pre-determined evaluative criteria. Accepting peer assessments requires students to engage with others' knowledge and skills, and, in the light of this, review their own interpretation and application of the pre-determined evaluative criteria. The use of peer assessment actively engages students in a key aspect of higher education: making critical judgements on the work of others (Rowland 2000, Boud, 1990). The use of 360 degree feedback with peer assessment can encourage students to engage critically with their own work, feedback on their own work and criteria employed in the evaluation of their work. Self assessment can similarly encourage students to engage more critically with their own work and the assessment criteria. “Education is what survives when what has been learned has been forgotten.” (B.F. Skinner, The New Scientist, May 21, 1964) 4 References Biggs, J. (1999) Teaching for Quality Learning at University, Buckingham: SRHE and Open University Press Boud, D. (1990) Assessment and the promotion of academic values, Studies in Higher Education, 15(1), 101-111 Cronin, J.C. (1993) Four misconceptions about authentic learning. Educational Leadership, 50(7), 78-80 Donovan, S., Bransford, J., & Pellegrino, J. (Eds). (1999) How people learn: Bridging research and practice, National Academy of Sciences [On-line]. Available: http://bob.nap.edu/html/howpeople2/. Last accessed 19.01.06 Elmore, R. F., & Rothman, R. (Eds.). (1999) Testing, teaching, and learning: A guide for states and school districts, Washington, DC: Academy Press Fosnot, C. T. (1996) Constructivism: A Psychological Theory of Learning, in C. T. Fosnot (Ed.) Constructivism: theory, perspectives, and practice, pp8-33, New York: Teachers College Press Gagne, R.M. (1985) The Conditions of Learning and Theory of Instruction, Fort Worth, TX: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, Inc. Heywood, J. (2000) Assessment in Higher Education, London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers Newmann, F.M. (1996) Authentic Achievement: Restructuring schools for intellectual qualit, San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Ramsden, P. (1992) Learning to teach in Higher Education, London: Routledge Rowland, S. (2000) The Enquiring University Teacher, Buckingham: SRHE and Open University Press Sartre, J.P. (1965) Anti Semite and Jew, (trans.) G.J. Becker, New York: Schocken Stefani, L.A.J. (1994) Peer, Self and tutor assessment: relative reliabilities, Studies in Higher Education, 19 (1) 69-75 Zariski, A. (1996) Student peer assessment in tertiary education: Promise, perils and practice, in Abbott, J. and Willcoxson, L. (Eds), Teaching and Learning Within and Across Disciplines, pp189-200, Proceedings of the 5th Annual Teaching Learning Forum, Murdoch University, February 1996. Perth: Murdoch University. [On-line]. Available: http://cleo.murdoch.edu.au/asu/pubs/tlf/tlf96/zaris189.html Last accessed 19.01.06. 5