Literary Terms for AP English IV

advertisement

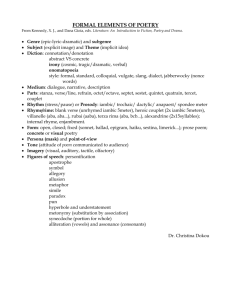

Literary Terms for AP English IV allegory Allegory occurs when one idea or object is represented in the shape of another. anagnorisis In drama, the discovery of recognition that leads to the peripety or reversal. anecdote A short narrative detailing particulars of an interesting episode or event. antistrophe One of the three stanzaic forms of the Greek choral Ode, the others being strophe and epode. It is identical in meter with the strophe, which precedes it. As the chorus sang the strophe, they moved from right to left; while singing the antistrophe, they retraced these steps exactly, moving back to the original position. In rhetoric antistrophe is the reciprocal conversion of the same words in succeeding phrases or clauses, as T.S. Eliot’s “The desert in the garden the garden in the desert.” aphaeresis (uh-FEHR-uh-sus) apocope (uh-PAH-kuh-pee) A type of elision in which a letter or syllable is omitted at the beginning of a word, as ‘twas for it was. A type of elision in which a letter or syllable is omitted at the end of a word, as in morn for morning. attitude An author’s, speaker’s, character’s opinion of or feelings toward a subject. Attitudes may shift either slightly or from on extreme to the other. Authors often create readers’ attitudes my manipulating characters’ attitudes. burlesque Any imitation of people or literary type that, by distortion, aims to amuse. Burlesque tends to ridicule faults, not serious vices. aubade A lyric about dawn or a morning serenade, a song of lovers parting at dawn. baroque The baroque is a blending of picturesque elements (the unexpected, the wild, the fantastic, the eccentric) with the more ordered, formal style of the high Renaissance. bathos The effect resulting from the unsuccessful effort to achieve dignity or sublimity of style; dropping from the sublime to the ridiculous. Breton Lay (Romance) A medieval French Metrical Romance, emphasizing love as the central force in the plot. Breton romances drew on the traditions of courtly love . caesura A pause or break in a line of verse. Originally, in classical literature, the caesura characteristically divided a foot between two works, usually near the middle of a line. comedy Compared with tragedy, comedy is a lighter form of drama that aims primarily to amuse. It differs from farce and burlesque by having a more sustained plot, weightier and subtler dialogue, more lifelike characters, and less boisterous behavior. conceit A long, complex metaphor. The term designates fanciful notion, usually expressed through an elaborate analogy and pointing to a striking parallel between ostensibly dissimilar things. concrete poem Poetry that exploits the graphic, visual aspect of writing; a specialized application of what Aristotle called opsis (“spectacle”). Poems in which the shape, not the words, is often what matters. Also called emblematic poetry. contra passo Let the punishment fit the crime. convention A device of style or subject matter so often used that it becomes a recognized means of expression. critique A critical examination of a work of art with a view to determining its nature and assessing its value according to some established standards. A critique is more serious and judicious than a review. detail Items or parts that form a larger picture or story. Authors choose or select details to create effects in their works or evoke responses from the reader. diction Sometimes used informally to refer to crispness of pronunciation. In linguistics, diction means word choice. dramatic monologue The speaker in a dramatic monologue is usually a fictional character or a historical figure caught at a critical moment. His or her words are established by the situation and are usually directed at a silent audience. The speaker usually reveals aspects of his personality of which he or she is unaware. elegy A poem that laments the death of a person, or one that is simply sad and thoughtful. elision enjambment (enjambement) The omission of a letter or syllable as a means of contraction, generally to achieve a uniform metrical pattern, but sometimes to smooth the pronunciation; most such omissions are marked with an apostrophe. Specific types of elision include aphaeresis, apocope, syncope, and synalepha, most of which can be found in Thomas Gray’s “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard.” The continuation of a complete idea (a sentence or clause) from one line or couplet of a poem to the next line or couplet without a pause. Enjambment occurs in run-on lines and offers contrast to end-stopped lines. epic question The request or question addressed to the Muse at the beginning of an epic; the answer constitutes the narrative of the work. epic simile An elaborated comparison. The epic simile differs from an ordinary simile in being more involved and ornate, in a conscious imitation of the Homeric manner. epiphany Literally a manifestation or showing-forth, usually of some divine being. It is thus an intuitive grasp of reality achieved in a quick flash of recognition in which something, usually simple and commonplace, is seen in a new light. exemplum One section of the medieval sermon—the part which set forth examples to illustrate the theme of text of the sermon. existentialism A group of attitudes (current in philosophical, religious, and artistic thought during and after the Second World War) that emphasizes existence rather than essence and sees the inadequacy of human reason to explain the enigma of the universe as the basic philosophical question. Fabliaux (fabliau) A humorous tale (often sly, bawdy satire) popular in medieval France. The conventional verse form of the fabliau was the eight-syllable couplet. feminine rhyme An extra-metrical unstressed syllable added to the end of a line in iambic or anapestic rhythm. The first four lines in Hamlet’s “To be, or not to be—that is the question:” soliloquy all have feminine endings. hamartia The error, frailty, mistaken judgment, or misstep through which the fortunes of the hero of a tragedy are reversed. Aristotle asserts that this hero should be a person “who is not eminently good or just, yet whose misfortune is brought about by some error or frailty.” heroic couplet Iambic pentameter lines rhymed in pairs. Horatian Satire Satire in which the voice is indulgent, tolerant, amused, and witty. The speaker holds up to gentle ridicule the absurdities and follies of human beings, aiming at producing in the reader not the anger of a Juvenal but a wry smile. Juvenalian Satire Formal satire in which the speaker attacks vice and error with contempt and indignation. It is so called because it is like the dignified satires of Juvenal. kenning A figurative phrase used in Old Germanic languages as a synonym for a simple noun. Kennings are often picturesque metaphorical compounds. Specimen kennings from Beowulf are “the bent-necked wood,” for ship; “the swan-road” for the sea. litotes A figure of speech in which a positive is stated by negating its opposite. Some examples of litotes: no small victory, not a bad idea, not unhappy. Litotes, which is a form of understatement, is the opposite of hyperbole. loose sentence A sentence grammatically complete before the end; the opposite of periodic sentence. masculine rhyme Rhyme that falls on the stressed, concluding syllables of the rhyme words. “Mont” and “fount” make a masculine rhyme, “mountain” and “fountain” make a feminine. Metaphysical conceit An ingenious kind of conceit widely used by the metaphysical poets, who explored all areas of knowledge to find, in the startlingly esoteric or the shockingly commonplace, telling and unusual analogies for their ideas. The metaphysical conceit often exploits verbal logic to the point of the grotesque, and it sometimes achieves such extravagant turns on meaning that it becomes absurd. Metaphysical poetry The characteristics of the best metaphysical poetry are logical elements in a technique intended to express honestly, if unconventionally, the poet’s sense of life’s complexities. The poetry is intellectual, analytical, psychological, disillusioning, bold; absorbed in thoughts of death, physical love, religious devotion. narrative pace The pace by which the story and events are developed. These methods may include diction, syntax, dialogue, shifts in tone, etc. narrative techniques Methods used in telling a story. These methods include (but are not limited to) point of view (of the writer), viewpoint (of a character), sequencing of events, manipulation of time, dialogue, or interior monologue. ode A lyric poem that is serious and thoughtful in tone and has a very precise, formal structure. pathetic fallacy A phrase coined by Ruskin to denote the tendency to credit nature with human emotions. In a larger sense the pathetic fallacy is any false emotionalism resulting in a too impassioned description of nature. It becomes a fault when it is overdone to the point of absurdity. peripateia The reversal of fortune for a protagonist—possibly either a fall, as in a tragedy, or a success, as in a comedy. stichomythia A form of repartee developed in classical drama and often employed by Elizabethan writers. It is a sort of line-for-line verbal fencing match in which the principals retort sharply to each other in lines that echo and vary the opponent’s words. Antithesis is freely used. synalepha (sin-uh-LEE-fuh) syncope (SIN-koh-pee) A type of elision in which a vowel at the end of one word is coalesced with one beginning the next word, as “th’ embattled plain.” A type of elision in which a word is contracted by removing one or more letters or syllables from the middle, as in ne’er for never. syntax The structure of a sentence; the juxtaposition of words in a sentence. Discussion of syntax in a work could include discussion of the length or brevity of sentences, the kinds of sentences (declarative, interrogative, exclamatory, imperative sentences, rhetorical questions; periodic or loose sentences; simple, complex, or compound sentences) and the impact on the reader of the author’s choice of sentence structure. terza rima A three-line stanza, supposedly devised by Dante with rhyme scheme aba bcb cdc ded and so forth. In other words one rhyme sound is used for the first and third lines of each stanza, and a new rhyme introduced for the second line, this new rhyme, in turn, being used for the first and third lines of the next stanza. The opening of Shelley’s “Ode to the West Wind” is written in terza rima. trope In rhetoric a trope is a figure of speech involving a “turn” or change of sense—the use of a word in a sense other than the literal. tone The writer’s attitude toward his or subject matter. For example, the tone can be angry, compassionate, melancholy, allusive, etc. verisimilitude The semblance of truth. The term indicates the degree to which a work creates the appearance of the truth. villanelle A fixed nineteen-line form, originally French, employing only two thymes and repeating two of the lines according to a set pattern. Line 1 is repeated as lines 6, 12, and 18; line 3 as lines 9, 15, and 19. The first and third lines return as a rhymed couplet at the end. The finest villanelle in any language—and one of the greatest modern poems in any form—is Dylan Thomas’s “Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night.” voice The term, voice, while often used synonymously with speaker or persona, can also refer to a pervasive presence behind the fictitious voices that speak in a work, or to Aristotle’s “ethos,” the element in a work that creates a perception by the audience or reader of the moral qualities of the speaker or a character. volta The turn in thought—from question to answer, problem to solution—that occurs at the beginning of the sestet in the Italian sonnet. The volta sometimes occurs in the Shakespearean sonnet between the twelfth and the thirteenth lines. The volta is routinely marked at the beginning of line 9 (Italian) or 13 (Shakespearean) by but, yet, or and yet. uxoriousness Excessively fond of or submissive to a wife. (Mr. McCollom’s favorite word in the world!)