The Hero`s Journey - College of the Redwoods

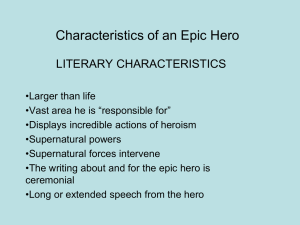

advertisement

Eng. 1B Holper THE HERO’S JOURNEY Myths are not simply romantic stories about super-human men and women who go out into the dangerous unknown on exciting journeys to fight monsters, bring back magic lanterns, rescue beautiful princesses, or find the husband or wife of their dreams. As Joseph Campbell points out in his class book The Hero with a Thousand Faces, stories of these mythological adventures are really metaphors and symbols for the “journeys” in life that all of us go through as we pass from one stage to another. On the deepest level, myths are maps that tell us what it means to be human. They show us the types of problems we face in our lives and how we deal with those situations to find meaning, wisdom, and joy. Campbell believes that across all cultures there is a pattern in many myths as to the stages that heroes pass through on countless journeys. Campbell describes 17 stages of this monomyth cycle. Some of the more noteworthy of these include the following: The Call: The hero hears a call to a quest. It can be forced on him by external circumstances, or it can be the deliberate choice of the hero to begin an adventure. Examples of this include Telemachus hearing the call from Athena to go and seek his father Odysseus. Or in a more modern context, Luke Skywalker is compelled to leave his home when his Uncle Owen and Aunt Beru are murdered; thus, he joins Ob-Wan Kenobi and begins to train as a Jedi knight. Allies: Certain individuals, such as friends, family members, guides, or even gods and goddesses, may show up as allies who will support the hero in various ways. Other allies may appear at different stages of the journey. A classic example of this is found in the story of Theseus and the Minotaur. Before Theseus ventures into the labyrinth, Ariadne gives Theseus a ball of string so that after he kills the monster he can find his way out. A modern example of this would be in the film The Matrix when Morpheus offers to both show Neo the truth of his situation, as well as later train him for his coming trials. False Allies: Sometimes it’s easy to be fooled by wolves in sheep’s’ clothing, and writers frequently use such characters to help us sort out those who are trustworthy from those who are not. An example of this in The Wizard of Oz: the Wizard seems to be an ally; however, because he doesn’t want to be revealed as a fake wizard, he sends Dorothy and her friends off on an impossible task, which he believes will get rid of her and protect his image. Preparations for the Quest: The hero decides what he will need to take with him—supplies, helpers, information—as he prepares for the great adventure. In some cases, certain people, being, situations, or even the hero’s own doubts and fears, may arise which can make it very difficult for him to leave on the quest. If such obstacles do appear, the hero will have to overcome these “guardians of the threshold” in order to begin the journey. An example of this can be found in The Fellowship of the Ring, in which Frodo obtains the ring from his Uncle Bilbo Baggins and is joined on his quest by three hobbit friends: Sam Gamgee, Meriadoc Brandybuck, and Peregrin Took. Crossing the Threshold: The hero begins the journey and crosses over to a strange new world where things are different. At this time, he is inexperienced and uncertain how to act. Also in the Fellowship of the Ring, as the hobbits depart the Shire, Sam looks around and tells Frodo that this is the farthest he’s ever gone in his life. As the move beyond this point, it’s apparent that all that they have known is about to change, and they are entering a quite different and dangerous world. Guardians of the Threshold: Often times when a hero crosses over from the known to the unknown, he or she must pass a guardian. Sometimes this involves passing a test or using a key. We see an example of this when mortal souls must encounter Cerberus (the three headed dog) that guards the entrance to Hades. Orpheus deals with Cerberus by lulling him to sleep with music. Road of Trials: One difficult experience after another will test the strength, courage, and wisdom of the hero. At times he may find himself stuck in a very difficult, depressing, or dangerous situation. It may even seem to him that he has no hope or chance of getting out of it. But this is often the time and place where in the darkest moment (the belly of the whale) the light and salvation come—or the hero discovers something in himself that allows him to persevere and triumph. An example of this is found in the film The Matrix when Neo seems to be beaten by his nemesis Agent Smith. However, at this point, Neo invites Agent Smith to assimilate him, which results in the end of both Smith and all his copies. Saving Experience or Person or Gift: The hero may meet a special person, such as a god or goddess, mother or father figure, who comes to help or to save him. Or he may have a powerful experience that transforms him. In some cases, he receives a gift or insight, or he achieves the journey’s goal. A contemporary example of this stage is found in The Return of the King, in which Frodo finally is overcome by the ring’s power, but his goal is nonetheless unwittingly accomplished by Gollum, who, overjoyed by regaining the ring, falls into the fires of Mt. Doom, thus destroying the ring. Apotheosis: To apotheosize is to deify. When someone dies a physical death, or dies to the self to live in spirit, he or she moves beyond the pairs of opposites to a state of divine knowledge, love, compassion, and bliss. This is a god-like state; the person is in heaven and beyond all strife. A more mundane way of looking at this step is that it is a period of rest, peace, and fulfillment before the hero begins the return. Transforming Changes/The Return: As the hero starts to change and understand his new experiences and new ways of thinking, he crosses back over to the everyday world. However, his normal world is not the same because he has changed and now sees things differently. A classic example of this stage is when Siegfried kills the dragon, tastes its blood, and is able to understand the language of the natural world. Or when Frodo is unable to remain in the Shire (after his adventure) and accompanies the elves across the ocean. Sharing the Gift: As a result of his journey, the hero has gained a gift, such as wisdom (and the power that comes with it), knowledge, and memorable experiences that he shares with his family and community. We see this stage in Frodo’s adventure when he nearly completes his written version of his story and then passes it on to Sam to complete after Frodo has departed. This pattern is not only applicable to fiction but also to the journeys that everyone goes through in the course of a lifetime (though not every quest perfectly matches this pattern). Some of our journeys are physical, such as in the case of refugees or immigrants who leave their homelands to settle in strange new worlds. Other journeys represent the stages and major experiences many of us face in life: moving to a new home, going to a new school, graduating from high school and college, starting a career, getting married, giving birth, raising children, encountering death, and preparing to die ourselves. On these journeys, while no real monsters are killed, real fears and problems are overcome; we move from dependency (as children) into the responsibilities of adulthood; we are invited to join into social systems; we form attachments, relationships. Some achieve success in being alive to life’s possibilities; others end up leading wasted lives, while some end up dying before their time—for the hero’s journey is real, and although it can be a great joy, it can similarly lead to spiritual and physical death. However, by better understanding the journey, we can become real-life heroes who by enduring life’s trials are made stronger and wiser. We thus become mature, fulfilled, and responsible adults who then go on to share our experiences and insights with our friends, family, and community. Because we have managed to save ourselves, we help to transform the world with our love, spirit, wisdom, and compassion. And that’s what the real hero’s journey is about. Archetypes, Myths, and Characters An archetype is a prototype or model from which something is based. The character archetypes listed here derive from Joseph Campbell's The Hero with a Thousand Faces and are deeply rooted in the myths and legends of many cultures. A significant character's role can often be associated with one of these archetypes, because storytelling is as old as these myths and legends and is how they were handed down to us. Archetypes connect your story to the rich heritage of all storytelling. Hero The essence of the hero is not bravery or nobility, but self-sacrifice. The mythic hero is one who will endure separation and hardship for the sake of his clan. The hero must pay a price to obtain his goal. The hero's journey during a story is a path from the ego, the self, to a new identity which has grown to include the experiences of the story. This path often consists of a separation from family or group to a new, unfamiliar and challenging world (even if it's his own back yard), and finally a return to the ordinary, but now expanded, world. The hero must learn in order to grow. Often the heart of a story is not the obstacles he faces, but the new wisdom he acquires, from a mentor, a lover, or even from the villain. Other characters besides the protagonist can have heroic qualities. This can be especially true of the antagonist. Heroes can be willing and adventurous, or reluctant. They may be group and family oriented, or loners. They may change and grow themselves, or act as catalysts for others to grow and act heroic. The hero can be an innocent, a wanderer, a martyr, a warrior, a vengeful destroyer, a ruler, or a fool. But the essence of the hero is the sacrifice he makes to achieve his goal. Mentor The mentor is a character who aids or trains the hero. The essence of the mentor is the wise old man or woman. The mentor represents the wiser and more godlike qualities within us. The mentor's role may be to teach the hero. These characters are often found in the roles of drill instructor, squad leader or sergeant, the older officer policeman, the aged warrior training the squire, a trail boss, parent or grandparent, etc. An effective teacher may be an otherwise inept or foolish character who possesses just the skill or wisdom the hero needs for his challenge. The other major role of the mentor is to equip the hero by giving him a gift or gifts which are important in his quest. These gifts may be weapons, medicine or food, magic, or some important clue or piece of information. Frequently, the mentor requires the hero to have passed some sort of test before receiving the gift. The gift may be a seemingly insignificant object, the importance of which doesn't emerge until later. The mentor may occasionally be the hero's conscience, returning him to the right path after he strays or strengthening him when he weakens. The hero doesn't always appreciate this assistance, of course. Threshold Guardian The threshold guardian is the first obstacle to the hero in his journey. The threshold is the gateway to the new world the hero must enter to change and grow. The threshold guardian is usually not the story's antagonist. Only after this initial test has been surpassed will the hero face the true contest and the arch-villain. Frequently the threshold guardian is a henchman or employee of the antagonist. But the threshold guardian can also be an otherwise neutral character, or even a potential ally such as the police lieutenant who warns the hero private detective off the case, or the Cowardly Lion who first frightens and then joins Dorothy on her journey to Oz. The role of the threshold guardian is to test the hero's mettle and worthiness to begin the story's journey, and to show that the journey will not be easy. The hero will encounter the guardian early in the story, usually right after he starts his quest. Herald The role of the herald is to announce the challenge which begins the hero on his story journey. The herald is the person or piece of information which upsets the sleepy equilibrium in which the hero has lived and starts the adventure. The herald need not be a person. It can be an event or force: the start of a war, a drought or famine, or even an ad in a newspaper. Shapeshifter The shapeshifter changes role or personality, often in significant ways, and is hard to understand. That very changeability is the essence of this archetype. The shapeshifter's alliances and loyalty are uncertain, and the sincerity of his claims is often questionable. This keeps the hero off guard. The shapeshifter is often a person of the opposite sex, often the hero's romantic interest. In other stories the shapeshifter may be a friend or ally of the same sex, often a buddy figure, or in fantasies, a magical figure such as a shaman or wizard. The shapeshifter is sometimes a catalyst whose changing nature forces changes in the hero, but the normal role is to bring suspense into a story by forcing the reader, along with the hero, to question beliefs and assumptions. As with the other archetypes, any character, including the protagonist and antagonist, can take on attributes of the shapeshifter at different times in the story. The hero often assumes the role of shapeshifter to get past an obstacle. Mentors often appear as shapeshifters. Shadow The Shadow archetype is a negative figure, representing things we don't like and would like to eliminate. The shadow often takes the form of the antagonist in a story. But not all antagonists are villains; sometimes the antagonist is a good guy whose goals disagree with the protagonist's. If the antagonist is a villain, though, he's a shadow. The shadow is the worthy opponent with whom the hero must struggle. In a conflict between hero and villain, the fight is to the end; one or the other must be destroyed or rendered impotent. While the shadow is a negative force in the story, it's important to remember that no man is a villain in his own eyes. In fact, the shadow frequently sees himself as a hero, and the story's hero as his villain. Trickster The Trickster is a clown, a mischief maker. He provides the comedy relief that a story often needs to offset heavy dramatic tension. The trickster keeps things in proportion. The trickster can be an ally or companion of the hero, or may work for the villain. In some instances the trickster may even be the hero or villain. In any role, the trickster usually represents the force of cunning, and is pitted against opponents who are stronger or more powerful.