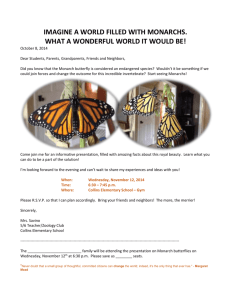

Good Neighbors

advertisement