ART AND LIFE IN VAN GOGH AND DOSTOEVSKY

advertisement

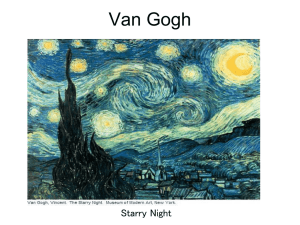

ART AND LIFE IN VAN GOGH AND DOSTOEVSKY (International Strategy Consultation ‘Choose life, so you and your children may live’, Hilversum, 13-5-2004) Arthur Zijlstra (Institute for Cultural Ethics, e-mail: azijlstra@che.nl) 1) Context * The context of this presentation is threefold: (a) geographically it is located in St. Petersburg, Washington and Amsterdam, (b) institutionally it is embedded in the Russian Museum (Boris Stolyarov), the Washington Arts Group (Jerry Eisley) and the Van Gogh Museum. See my article ‘Werken met licht’, in: Beweging (herfst 2001), pp 10-13; © framework: the International Dutch-Russian Center (Open Christianity), overall aim is the shaping of a civil society in Russia through international cultural and educational exchange. * I will give a polyphone type of presentation [cf. Mikhail Bahktin’s interpretation of Dostoevsky: a cacaphony of different voices, in dialogue with an open end, creating ambiguity as it comes to Dostoevsky’s own perspective (RE, 29, 30; DS, 12). In my opinion Bahktin gives a much too post-modern interpretation, for the author of the text does not disappear (RE, 150), but his position towards his characters is radically changed (DS, 44, cf. 21)]: most of my spoken text will be on Dostoevsky, whereas my sheets will exclusively draw attention to Van Gogh. 2) Introduction: prophets in a spiritual crisis * In these reflections I want to draw your attention to a number of striking parallels between the Russian writer Fjodor Dostoevsky (1821-1880) and the Dutch painter Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890). I focus them upon their wrestling with the (nihilistic) consequences of modernity. Both artists may be called 19th century prophets with a 21st century message. They were far ahead of our present post-modern condition characterized by multiculturalism, constructivism, consumerism and secularism. Walter Nigg states in his Van Gogh book that Van Gogh, like Kierkegaard, Dostoevsky and Nietzsche, had a prophetic intuition of an upcoming catastrophe in European culture. ‘... es ist fast unheimlich, wie nahe er sich hierin mit Kierkegaard, Dostojewskij und Nietzsche berührt.’ (pp 50-51, cf. p. 9) * Living on the margins of their societies, hardly getting any public recognition during their lifetime, both Van Gogh and Dostoevsky tried to overcome the spiritual crisis in modernity, then characterized by new phenomena like naturalism, industrialism, historicism and atheism. They did not thereby give in to the superficialities and triviliazations of modern life (cf. hedonism and consumerism, RE, 75, 149-50 to quote on the man-god). * A note on the prophetic character of Dostoevsky’s work: ‘a mirror held up before the reader; it is the thoughts of our hearts that are disclosed’(RE, 141). ‘... Dostoevsky’s (and also Van Gogh’s, AZ) art .... retains the power to “burn the hearts” of those who hear it’ (RE, 2, 3 en 141). Prophecy is both in Van Gogh and Dostoevsky connected with the apocalyptic nihilism as expression of Western cultural crisis (RE, 14, 74). [‘Christ as a cosmic, apocalyptic figure who tears open the hidden meaning of everyday life’(RE, 9)]. Nihilism can be interpreted as the complete negation of life (and art) * The Russian philosopher Berdiaev on the historical significance of Dostoevsky: ‘So great is the woth of Dostoevsky that to have produced him is by itself sufficient justification for the existence of the Russian nation in the world.’ (DS, 1) I do not think the same can be said about Van Gogh’s importance for the world that ‘to have produced him is by itself sufficient justification for the existence of the Dutch nation in the world’. 1 * As Dostoevsky is concerned, we concentrate upon his magnum opus The Brothers Karamazov (1880), whereas for Van Gogh we tune in on his less known paintings The resurrection of Lazarus (1890) and The Sower. In finding my way around, I profited very much from four recently published excellent books, namely (1) Anton Wessels, ‘A Kind of Bible. Vincent van Gogh as Evangelist (London: SCM Press, 2000); (2) Walter Nigg, Vincent van Gogh. Der Blick in der Sonne, Zürich: Diogenes, 2003; (3) P. Travis Koeker and Bruce K. Ward, Remembering the End. Dostoevsky as Prophet to Modernity (Boulder, Col.: Westview Press, 2001) and (4) Marina Kostalevsky, Dostoevsky and Soloviev: The Art of Integral Vision, New Haven/London: Yale University Press, 1997 (= DS). These four books are invaluable sources of insight and inspiration. 3) Nihilism as consequence of modernity’s spirit of annihilation * In a certain sense both Dostoevsky and Van Gogh responded in their artistic work to the challenges of the Western (Enlightenment) project of modernity, more specific its (coming) crisis. My thesis is that, contrary to widespread opinion among intellectuals or intelligentsia, Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) was not the first thinker in Europe to live through nihilism and reflect upon it. In Dostoevsky’s work we find an earlier (in his novel Demons he is dealing with nihilistic and liberal utopianism among the 1860s generation of Russian intelligentsia; cf. Turgenew’s novel Fathers and Sons of 1861) and deeper [cf. Berdiaev: ‘Dostoevsky knew everything Nietzsche knew ... and more’, (RE, 142)] attempt to wrestle and overcome the experiences of meaninglessness as caused by modernity’s crisis. Nietzsche admitted to have learned from Dostoevsky’s approach and appreciates him especially for his psychological sensitivity. * Nietzsche discovered Dostoevsky in 1887 when he got a copy of Notes form the Underground. He was thoroughly familiar with all Dostoevsky’s major works, except The Brothers Karamazov (RE, 144). In sum, Nietzsche was influenced by Dostoevsky, whereas the latter never knew Nietzsche (cf. RE, 247: Nietzsche on Dostoevsky’s Jesus). Dostoevsky, and to a certain extent also Van Gogh, precedes or anticipates Nietzsche’s annunciation of the death of God and its moral and existential consequences (such as the experience of meaninglessness, RE, 74). * In Van Gogh, who like Nietzsche could only find spiritual rest under the abundant sun-light of the Mediterranée (cf. Nigg, p. 98), we especially notice a critique on the social and ecological consequences of 19th century industrialism. He wants to bring comfort and light to ordinary people (farmers in the country side, labourers and prostitutes in the city, as depicted in social realist novels) who suffered under the evils brought about by so-called scientifictechnological ‘progress’. He paints them as icons of God. In the words of Walter Nigg: ‘Bei ihm (Van Gogh, AZ) findet sich jenes religiöse Menschenpathos, das man im Zeitalter der Entmenschlichung und der vollendeten Gottesferne nicht mehr für möglich gehalten hat. Durch seine Würdigung des Menschen ist er zum Rembrandt des neunzehnten Jahrhunderts geworden, ... (p. 86). Or even more impressive: ‘Das war seine innerste Sehnsucht, die ihn ganz zum Brennen brachte: Menschen aus der Gegenwart darzustellen, die das Anlitz der modernen Zeit tragen und die doch etwas Verwandtes mit den Urchristen haben! Nie ist auf religiös-künstlerischem Gebiet etwas Größeres erstrebt worden.’(p. 113) * Besides that, Van Gogh strives after a rehabilitation of nature after its annihilation (an important aspect of nihilism), as can be seen in the themes and colours of his French period in the Provence. Ultimately, nature will be restored just as Lazarus was raised from the death by Jesus, who in Van Gogh is symbolized by the sun (an allusion to traditional lightmetaphysics?). Walter Nigg writes: ‘Das Erleben der modernen Wirklichkeit als etwas Göttliches gilt es zu sehen, will man seinem innersten Feuer nahekommen.’ (p. 13, cf. pp 8283, 118-119) Nowadays, Van Gogh could be seen as the patron of sustainable development, 2 a reorientation of our culture in order to integrate economy and ecology in a more harmonious way. * Dostoevsky on his turn comes to similar themes, starting however with a critique on the modernist ideal of progress (as formulated by Hegel and Marx). Ivan symbolizes this position in his famous story of the Grand Inquisitor. The idea of progress is self-refuting for (1) there is an inbuilt tension between the necessity of the historical process and the freedom and responsibility of man; further (2) it creates unresolvable tensions between individual freedom and collectively enforced equality; finally (3) it immanentizes or secularizes the biblicaltranscendent goal or meaning of history: the New Jerusalem, resulting in experiences of meaninglessness and nihilism (RE, 77). * Concerning this third argument: the modern idea of progress generates, according to Dostoevsky, its own nihilistic consequences (RE, 77). Historicism relativizes all possible (transcendent) truths and meanings by making them a result of the historical process themselves (RE, 73). This implies for Dostoevsky the end of all political utopias. Cf. Karl Löwith, Von Hegel zu Nietzsche (Hamburg: Meiner, 1981). The Great Inquisitor sympathizes with Hegels idea of progress in history, e.g. his three stages in world history (RE, 60 e.v.). There is a fundamental difference of opinion concerning the ultimate end of history: tyranny vs. freedom. * Furthermore, the idea of progress restricts itself to innerworldly forms of retributive justice. The wisdom and love of the monks and starets (Zosima) reveals more truth than the abstract and isolated theories of modern intellectuals. They are striving after a restorative justice coming from beyond our created reality. Dostoevsky’s critique og the Western ideal of progress finds its parallel in Nietzsche’s criticism of the modern ideal of progress as a secularized form of Christianity (RE, 144-145). * As nature is concerned, Dostoevsky fits in the broader 19th century Russian intellectual context (e.g. Bulgakov, Soloviev) that accentuated the importance of humanity’s participation in the cosmic fall and redemption (resurrection) of creation. See my articles on Bulgakov. In his book The Philosophy of Economy, he gives a fascinating quote from The Karamazov Brothers: ‘Love all God’s creation, the whole and each grain of sand in it. Love every leaf, every ray of God’s light! Love the animals, love the plants, love everything. If you love everything, you will perceive the divine mystery in things.’ 4) A corn of wheat: biblical symbolism in Dostoevsky and Van Gogh * Both in Van Gogh as in Dostojewski there is a really fascinating expression of biblical symbolism, a symbolism intending to overcome the critical experiences of nihilism (the abyss of nothingness after the Nietzschean death of God) and aiming at the restoration and rediscovery or recollection of meaning (RE, 138, 154). The image or better parable of the sower (see Matthew 13:2-9, Luke 8:1-4 and Mark 4:13-20) functions as a hermeneutical key towards understanding both Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov and many of Van Gogh’s paintings. Van Gogh made more than thirty variants of the sower. It alludes, firstly, to his calling as a painter-evangelist, and secondly to Christ as the sower of the Word of God. Kroeker and Ward write: ‘Christ’s parable of the sower is the master metaphor of the novel’ (RE, 19). * The epigraph of The Brothers Karamazov also gives expression to the metaphor of the seed. It is taken from John 12:24 which says: ‘Verily, verily, I say unto you, Except a corn of wheat fall into the earth and die, it abideth alone; but if it die, it bringeth forth much fruit.’ Jesus is speaking these words to calm down the earthly expectations of the crowd after his resurrection of Lazarus from the death (John 11). He is alluding to his own death and resurrection. As you remember, the story of Lazarus’ resurrection is the central clue in Crime 3 and Punishment, the prostitute Sonja reading it to Raskolnikow just after he killed Lizaweta. Many years later, being imprisoned in Siberia, he remembers this crucial scene and starts another, that is a new life. * My claim is that Van Gogh’s painting ‘The resurrection of Lazarus’, painted several months before he died (May 1890), is the hermeneutical key to disclose his whole oeuvre as an artist. Like Dostoevsky he was convinced that the nihilistic consequences of modernity (ending up in spiritual and cultural death) could only be overcome by an act of transcendence, that is through the power of the resurrection or to put it this way: the victory of light over darkness (cf. the Russian-Orthodox view of Christ’s mission, as Wessels points to in his Van Gogh book). It cannot be accidental that both for Dostoevsky and Van Gogh the chapters 11 and 12 from the gospel of John were so central in their lifes. In fact, it was their most important message, as can still be seen at Dostoevsky’s grave monument in St Petersburg which quotes John 12:24. Walter Nigg writes at the final page of his Van Gogh book that someone read this same verse during the burial of Van Gogh (p. 136) in order to approach the secret of Van Gogh’s life and death (cf. also Nigg, p. 108). * The seed symbolizes for Dostoevsky the meaning of life, as in Father Zosima’s remark: ‘Only a little, tiny seed is needed and it will serve as a hidden reminder of the true meaning of life. ... All creation witnesses the beauty of divine mystery by ceaselessly enacting it, for the Word is for all, all creation and all creatures, every little leaf is striving towards the Word of God, sings glory to God, weeps to Christ, unbeknownst to itself, doing so through the mystery of its sinless life’(RE, 19) * The christian realism of Dostoevsky, as expressed in the epigraph of The Brothers Karamazov (John 12:24) is symbolized by Alyosha, who is called by his spiritual father, the elder Zosima to love his fellow-humans by sojourning through the world (RE, 13-14). To a certain extent the spiritual conflict or antithesis between (post-)modernity’s nihilism and Dostoevsky’s christian realism is reflected by the conflicting spiritual directions of Ivan and Alyosha Karamazov. The epigraph is ‘the central prophetic claim of the novel: that only by dying to the isolation of immanent earthly realism can one become alife to life itself and thus “bear fruit”’ (RE, 20). * P.M. Dostoevsky sees a parallel between seeds and ideas: both go through a mysterious process of becoming independent from their author and laying a hold on people’s minds (RE, 66) * The restoration of meaning both in Van Gogh and Dostoevsky goes along the way of a corn of wheat, that is through (spiritual and/or bodily) death. Both sower and seed must die in order to be reborn into new life and new vision. Postmodern nihilism, in Nietzsche’s slipstream, denies this possibility of a re-creation or transformation from emptiness, loneliness and uprootedness into a new and better fullness of life, ultimately because its hermeneutics of suspicion cannot cope with the experience of love. Another quote of Nigg, illuminating the deep affinity between Van Gogh and Dostoevsky: ‘Die Sonne symbolisiert den zum Leben erweckenden Christus. ... Auch Dostojewskij lag die gleiche Überlegung zugrunde, wenn er in seinem Großinquisitor-Poem Christus kein Wort reden läßt.’(p. 128) 5) Rediscovering meaning by affirming ordinary life * Meaning will not be found in an otherworldly realm, be it a future utopia or a platonic heaven of eternal ideas. Both Van Gogh and Dostoevsky state that meaning can only be found in this world, on the condition that it is seen as being created by God. That is, reality is not an autonomous, in itself enclosed whole or globalising world-system; history as such not a necessary process of progress in which human freedom and responsibility is only superficial and without an ultimate telos. On the contrary, for both artists this world gets its 4 meaning by referring in a mysterious way to the Lord of heaven and earth. They adhere to a coram Deo perspective. Nigg says that Van Gogh’s art presents a new way of giving meaning to life and therefore has a metaphysical inclination (pp 12-13). * In Dostoevsky we see the affirmation of ordinary life (cf. Charles Taylor on the puritan tradition in Sources of the Self) as a source of transcendence, e.g. reflected in his criticism of utopian ideologies as liberalism and socialism but also in Zosima’s advise to Alyosha to sojourn as a monk through the world and to love his fellow human beings. Dostoevsky’s interpretation of Russian-Orthodox Christianity does not lead him to a world-avertive religion (as Nietszche would rightfully condemn, cf. RE, 111, 172), but wants people to experience meaning by loving one another and thereby constituting a new humanity that will ultimately be transfigured into god-manhood. Dostoevsky’s alternative for world-avertive forms of Christianity may be called worldly monasticism. Cf. Bulgakovs sympathies for protestantism in this regard in his essay ‘Heroism and the Spiritual Struggle’. * The concept of meaning as ‘innerworldly transcendence’ (that is ordinary life coram Deo as a source of meaning) is meant by Dostoevsky as a powerful argument against the instrumentalization of creation and history as only a means for a future goal or end (telos) without an irreducible meaning of its own. Again, let us listen to Nigg: ‘Van Gogh wurde zum Maler des Enthusiasmus und der Lebensbejahung, .... Es ist ein neues Lebensgefühl, das nicht mehr das Diesseits als Jammertal empfindet, aber auch nicht einfach das Jenseits dem Diesseits opfert. Vielmehr erlebte Vincent alle Immanenz als etwas Transzendentales und alle Transzendenz als etwas Immanentes.’(p. 101) Nigg coins then the apt phrase of Van Gogh’s ‘charismatic realism’ (p. 105 en 108) or ‘realistic symbolism’ (p. 121). * Nietzsche and Dostoevsky agree with the statement that the love of God and the love of humanity mutually presuppose one another, wheras Ivan Karamazov sees only a tension, not to say an opposition between them. The fundamental difference between Dostoevsky and Nietzsche concerns the experience of love as (non-reducible, AZ) love, despite all suffering, and not as enlightened egoism (RE, 171). Note in this regard also Dostoevsky’s prophetic Pushkin speech in Moscow in June 1880 on the ideal of universal brotherhood, the pan-human ideal of love and reconciliation among the nations in which Russia has to fullfill its specific world-historical mission (DS, 71-77; RE, 10-13) * Van Goghs theology has been called a comprehensive creation theology (cf. Wessels). This is not the same as a mystical pantheistic worldview, as he has been accused of by some interpretors. To him both nature and mankind are sources of innerworldly transcendence. To be more precise: especially the suffering, poor people; the farmers and labourers of his day. In many of his paintings they get a kind of halo as if they were icons. In a certain sense they really are: icons of ordinary life. Icons that, according to Dostoevsky and Soloviev, are heading at their future transfiguration into God-manhood (opposed to Nietzschean man-godhood). * Both in Van Gogh and Dostoevsky the themes of dead and resurrection, of light’s victory over darkness structure and determine their work (for The Brothers Karamazov, see RE, 18). Those are hermeneutical keys to get a deeper understanding of the meaning of their work. Mainstream secular interpretations do not do justice to them in this regard. 5 Literature N. Ashimbaeva & V. Biron, The Dostoevsky Museum in St. Petersburg. A Guide book, St. Petersburg, 2000 Craig Barthelomew (ed.), In the Fields of the Lord. A Calvin Seerveld Reader, Carlisle: Piquant, 2000 Sergius Bulgakov, The Bride of the Lamb, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2002 Sergius Bulgakov, The Friend of the Bridegroom. On the Orthodox Veneration of the Forerunner, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003 Sergej Bulgakov, Philosophy of Economy. The World as a Household, New Haven/London: Yale University Press, 2000 Sergii Bulgakov, Towards a Russian Political Theology, Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1999 Ruth Coates, Christianity in Bakhtin. God and the Exiled Author, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998 Fjodor Dostojewski, Dagboek van een schrijver, Amsterdam: Van Oorschot, 2001 (Verzamelde werken, dl. 10) Fjodor Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov, New York: Vintage, 1990 Felix Philip Ingold, Der Name des Nichts. Nietzsche bei den Russen: Neues zu seiner Wirkungsgeschichte, in: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (FAZ), 19-9-2001 (katern Feuilleton) Marina Kostalevsky, Dostoevsky and Soloviev: The Art of Integral Vision, New Haven/London: Yale University Press, 1997 (= DS) Walter Nigg, Vincent van Gogh. Der Blick in der Sonne, Zürich: Diogenes, 2003 Oliver O’Donovan, Resurrection and Moral Order. An Outline for Evangelical Ethics, Grand Rapids/Leicester: Eerdmans / Apollos, 1994, 2nd ed. P. Travis Koeker and Bruce K. Ward, Remembering the End. Dostoevsky as Prophet to Modernity Boulder (Col.): Westview Press, 2001(= RE) Stephen Lovell, Summerfolk. A History of the Dacha, 1710-2000, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2003 George Pattison & Diane Oening Thompson, Dostoevsky and the Christian Tradition, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001 Esther Reed, The Genesis of Ethics. On the Authority of God as the Origin of Christian Ethics, London: Darton, Longman & Todd, 2000 Mark Roskill (ed.), The Letters of Vincent van Gogh, London: Flamingo/Harper Collins, 2000 Marina Rumjanzewa, Die Verschlechterung der Welt. Über die russischen Wurzeln des Terrorismus als Nihilismus, in: Neue Zürcher Zeitung (NZZ), 26-11-2001 (katern Feuilleton) Rüdiger Safranski, Nietzsche. Biographie seines Denkens , München: Carl Hanser Verlag, 2000 Alexander Schmemann, For the Life of the World. Sacraments and Orthodoxy, Crestwood (New York): St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2002, reprint of 2nd ed. 6 Deborah Silverman, Van Gogh and Gauguin. The Search for Sacred Art, New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2000 Vladimir Solovjov, Korte vertelling van de antichrist, Bergen op Zoom: Perun Boeken, 2003 Solomon Volkov, St. Petersburg. A Cultural History, New York, The Free Press, 1995 Anton Wessels, ‘A Kind of Bible. Vincent van Gogh as Evangelist, London: SCM Press, 2000 Carol Zemel, Van Gogh’s Progress. Utopia, Modernity and Late-Nineteenth-Century Art, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1997 Arthur Zijlstra, De geest van de economie bij Sergei Boelgakov, in: Beweging (najaar 2003), pp 16-19 Arthur Zijlstra, De humanisering van de natuur. Sergei Boelgakov over de relatie mens-natuureconomie, in: Nederlands Theologisch Tijdschrift, vol. 58, nr. 2 (april 2004), pp 142-159 Arthur Zijlstra, Van Gogh Bezinning, in: Vierkrant (orgaan van de Nieuwe Kerk gemeente in Ede), Pasen 2003, pp 20-25 Arthur Zijlstra, Van Gogh’s Critique of Modern Culture. A Philosophical Perspective, St. Petersburg, 22-5-2003 (unpublished paper) Arthur Zijlstra, Werken met licht, in: Beweging (herfst 2001), pp 10-13 7