file

advertisement

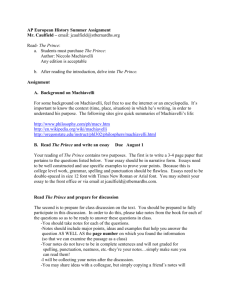

“Yes, Prince.” Machiavelli’s Echo in Management by Dr Michael Jackson, Professor Emeritus and Dr. Damian Grace, Honourary Associate Department of Government and International Relations University of Sydney Presented at the Australian Political Studies Association Annual Conference Canberra 2011 2 “Yes, Prince.” Machiavelli’s Echo in Management Long before “Yes, Prime Minister” there was “Yes, Prince!" Before Antony Jay gave television viewers “Yes, Minister” and its successor “Yes, Prime Minister” he published a ground breaking and vastly successful book called Management and Machiavelli (1967). Though Niccolò Machiavelli never managed anything, and said nary a word about business or commerce, he has become a frequently invoked spirit in management study. His DNA now marks a good deal of both the popular and professional literature in management following Jay’s book. A steady stream of other works have since appropriated Machiavelli to management, commerce, and business. By means of parallels, analogies, metaphors, long bows, sleights of hand, and other literary tropes, including even some downright lies, he has been resurrected in the corporate world's book trade. Whatever the means, Machiavelli now occupies a place in the pantheon of management thinkers. There he sits somewhere between Peter Drucker and Alfred Sloan. Comprehensive encyclopaedias and crisp dictionaries of management feature an entry on the Florentine, and a surprising number of trade books feature his name, as do articles in business research journals. Despite the number and variety of references to Machiavelli in the management literature, this conscription of Machiavelli passes unnoticed by students of Machiavelli in political science and history. This paper surveys what is said about Machiavelli and management. It notes that the two most important steps in the induction of Niccolò is to equate Sixteenth Century Florence with contemporary life and then to assert that business is analogous to war and diplomacy as experienced by Machiavelli. While documenting the ways Machiavelli is used and abused in the management literature, this paper will concentrate on these two master narratives as a nested equation: F = M, where “F” is Florence of the 16th Century and “M” is contemporary life, and then P = B, where “P” is politics as Machiavelli witnessed it and “B” represents business, commerce, and management today. We show that these equivalences are hallow, self-serving at best and deceptive at worst. Yet the questions remains: Why does Machiavelli continue to exercise such an allure over the imagination? One simple answer is that his popularity in the management literature arises less from his penetrating insights into his own world, though these were many, than with his salacious reputation, which is largely undeserved. 3 A middling Italian civil servant died on 27 May 1527. Having served on a number of foreign missions, his only published book was on the organization of a civil militia, where he had no success himself. Within less than a generation his name became and remained an adjective for evil, but that is another story. Apart from that infamy, Niccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli’s subsequent place in Western consciousness has been confined to those few dedicated to the study of the history of political thought, Renaissance history, and Italian literature, and mainly it has been based on his unpublished works, particularly The Prince and The Discourses. Successive generations of students required to do History of Political Thought (HPT) for a political science major have provided a sufficient market, together with students of Renaissance and Italian history and literature, and some Great Book readers to keep Machiavelli’s books in print. No doubt some other readers are titillated by that reputation for evil. There has always been a black market for Machiavelli’s Prince, which ignores the exchange rate and other regulations of the specialist markets in history and political theory. This dark readership, it has been alleged, includes Joseph Stalin, Idi Amin, and Benito Mussolini. And if they did, so too perhaps did other politicians of lesser infamy. Even so, all in all, it is a small slice of the reading public. However, Machiavelli has developed a whole new second life in other fields, largely neglected by the gravitas of political theory and kindred specialities. Machiavelli has been conscripted in management. That he had no management experience, or any interest in business has not barred him from a place of increasing prominence in this field. It all began with a thunderclap. Antony Jay, he of “Yes, Minister” fame (so uncritically favoured in political science departments) published Management and Machiavelli (1967). With that book Machiavelli was reborn an avatar, and since then Niccolò’s shade has known no rest. For a start Management and Machiavelli has remained in print since then, and that is now more than forty years to date, and gone through an array of editions to astound we who publish academic monographs in runs of five hundred, usually less, in these days of on-demand publication (with no numbers given). If Jay had published his books the other way around, with Yes, Minister first, he might have capitalized on the success of that title by at least subtitling Management and Machiavelli with Yes, Prince. Who knows, perhaps a future edition will be so titled! Once Machiavelli was thus re-born others followed Jay integrating him still further into the service of management. As we shall demonstrate presently, Machiavelli enjoys a considerable following among management writers, scholars, and readers, but this fact is all but invisible among political theorists. But when university research managers demand evidence for the impact of 4 political theory might one point to Machiavelli and management? Is Machiavelli’s fame among managers really unknown to the specialists? Here is some evidence. An examination of twelve translations and editions of The Prince at hand (called an opportunity sample in some scientific fields) reveals no reference and though each of them has some editorial and scholarly paraphernalia, there is in none of them a word in the introduction, forward, afterword, notes, or essays to indicate that Machiavelli has a following among managers. (These editions are: Gauss 1952, Bull 1961, Richardson 1979, Donno 1981, Atkinson 1985, Mansfield 1985, Skinner 1988, Alvarez 1989, Nederman 2007, McMahon 2008, Constantine 2009, and Marriott 2010). In addition, we consulted an array of textbooks on the History of Political Thought, since most students learn the political thought that they learn from such tomes, and found not one single reference to management and Machiavelli. (The texts are: Bluhm 1978, Strauss and Cropsey 1987, Plamenatz 1992, Sabine and Thorson 1993, McClelland 1998, Ebenstein and Ebenstein 1999, Wolin 2006, and Haddock 2008). Finally we turned to the gold standards of the Cambridge History of Political Thought, 1450-1700 (1991), the Oxford Handbook of Political Theory (2006), the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (2009), and the Oxford Handbook of the History of Political Philosophy (2011). They are likewise mute on Machiavelli’s second life on the shelves of management. (Indeed the only source we have found in the specialist literature on Machiavelli that refers to his second life is The Cambridge Companion to Machiavelli (2010), whose editor John Najemy has a paragraph about it (p. 6). That said, this paper brings to light in political theory some of Machiavelli’s second, double life. This paper (1) catalogues the extent of Machiavelli’s moonlighting in management with an emphasis on Jay's book, (2) identifies the main themes in this appropriation which are the equation of his times to our own and business to politics, of F=M/B=P, (3) it evaluates these appropriations, and (4) it closes with a few comments on the integrity of Machiavelli’s very distinct and limited political thought, and a note on some of the most egregious factual errors made in this management literature. Along the way, we try to steer clear of the Charybdis and Scylla, those absolute poles of contextualism and textualism. We neither wish to confine Machiavelli to 15th Century Florence, nor to license his aphorisms for eternity. But we do advocate moderation, caution, and qualification in the embrace of his ideas, arguments, and examples. Machiavelli himself was neither a contextualist nor a textualist. He took maxims from ancient Rome with enthusiasm and occasionally revised them for his own purposes. As we read the works of the Williams Shakespeare and Faulkner to reflect on the human condition and our own experiences of it, so we can read Machiavelli. 5 1. The thunderclap. Management and Machiavelli fused. First came the thunderclap, then the rain, and finally the flood. Make no mistake that it has become a flood, with our admittedly broad definition of the management literature we have added eight-five (85) items to a bibliography of management and Machiavelli. There is only one isolated title that associates Machiavelli with business, commerce, or management before 1967: as we noted, it is the publication of Antony Jay’s Management and Machiavelli that announced his entry into the field of management. That makes it the thunderclap. It is safe to say that Jay’s book had no precedent; it is equally safe to say that it was itself a precedent quickly followed. We have found only two previous references to Machiavelli by those examining management (the ecumenical term used in these pages to incorporate business, career, and commerce as well as management), though to be sure there were some and these will be noted. It is a credit to Jay’s ingenuity and wit, and no doubt to his salesmanship, that he connected Machiavelli to management in the first place and convinced a major British publisher to market the book. Our efforts to compile the metadata of his book yielded six editions. The first edition had no subtitle and neither does the current Kindle edition. Between those bookends, four subtitles have been used. They: • An inquiry into the politics of corporate life (1976), • Power and authority in business life (1987), • Discovering a new science of management in the timeless principles of statecraft (1994), and • A Prescription for success in your business (2000). Subtitles both attract the interest of prospective buyers and readers, and indicate the intentions of the author and publisher. Subtitles usually sharpen the focus of a work. In this case the focus is management, though ‘politics’ and ‘statecraft’ are mentioned, they are in a lesser key. We found no changes in the substance of the book through these editions. Short, new forewords are inserted and pagination has changed over the years from one publisher to another but not the content. The subtitles and other metadata came from searches of online catalogues of the Library of Congress, the Canadian National Library, the Australian National Library, and the British Library. Amazon’s web page claims, as does the cover the 1994 paperback edition that 250,000 hardcover copies have been sold, parroting the claim made on the cover of the 1994 paperback edition. We may safely assume many more copies have been sold since then. Moreover, that total refers to hardcover only and the book has been available in paperback for many years. Subsequent hardcover sales along with paperbacks must add considerably to that figure. In addition, the cover also claims it has been translated into twelve languages, though they are not listed. We can confirm that translations of the book appear in 6 the online catalogues for the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris, Biblioteca Italiana in Rome, and Deutsche National Bibliotek in Leipzig. Perhaps that is enough to make the point that though the rebirth of Machiavelli in management begin in English it has echoed in other major languages. Management and Machiavelli has indeed been a very successful book in this respect, too. Few, if any, of the learned works on Machiavelli’s political thought like Leo Strauss Thoughts on Machiavelli can have equaled these sales. These sales figures and the dissemination they imply stand partly as a surrogate measure of readership and impact more generally. Many of the hardcover copies are no doubt in libraries. We found Management and Machiavelli in many university library online catalogues, too many to list, starting with our very own University of Sydney library and others in the city of Sydney. The book has also been successful in another sense. It has made a major impact on the literature and study of management. This claim is fourlegged: (1) citations in social science literature, (2) references in Author Title Niccoló Machiavelli The Prince (1532) the popular press, (3) mentions of Jay's book in standard reference works in business and management, and (4) the flood of subsequent titles that press Machiavelli into the service of management, though not all of the subsequent works cite Jay, and some claim to themselves to have discovered the pertinence of Machiavelli to management! Such is on fate for prophets, as Niccolò Machiavelli said. First, we did a Cited Reference Search on the Web of Science. Of course, the Thomson databases that underlie the Web of Science have limitations yet they are used as a measure of everything, as those engaged in the research evaluation exercise, under its changing names, well know. The Web of Science is but one tool but it suffices to indicate the impact of Management and Machiavelli. To provide context we compared it to The Prince by Machiavelli and Leo Strauss’s Thoughts on Machiavelli, as one of the seminal studies of Machiavelli in political theory, only counting citations for each book after the publication of Management and Machiavelli in 1967. Hits July 2011 425 Leo Strauss Thoughts on Machiavelli (1959) 244 Antony Jay Management and Machiavelli (1967) 118 TOTAL 787 7 (Notes. Any edition of Jay’s Management and Machiavelli was included. This process is cumbersome, and so the counts are subject to a slight error. We noticed increases in citations for Machiavelli in years when new translations appeared.) Jay’s Management and The third leg is this, there Machiavelli has about a quarter are a number of important citations of the citations of reference works in the study and Machiavelli’s The Prince itself. practice of management and This would seem to be noteworthy. business. Invariably these mention Likewise, it has nearly half the hits Machiavelli and in so doing they of Strauss’s landmark work on also mention Jay. Since nearly all Machiavelli. The serious students of these reference works have of Machiavelli can take comfort in appeared since the publication of the fact that the book itself and one Jay’s book, we conclude that Jay of the most serious studies of it brought Machiavelli into the world, have more citations in the of management. Of course, publications included in Web of reasoning from a hypothetical Science. But we would do well to counterfactual is risky but our remember, as many researchers reasoning is nonetheless that had claimed throughout the recent Jay not published his book, Excellence in Research Australia Machiavelli would not have been exercise, that there is much deemed important enough to be outside the Thomson world. included in most the management Second are references to reference works in which he is now Jay in popular press and media. included. The reference works that For one example, Ken Roman in include Machiavelli with a the Wall Street Journal in 2007 reference to Jay are: Price (1996), names Jay’s Management and Witzel (2003), and Harris (2009). Machiavelli as one of the best five Other surveys of management business books listing it second. thinkers also include Machiavelli This seems to mean best, period, without explicit mention of Jay’s of all times and places: Platonic. Management and Machiavelli, like At the least, Jay was at the head of George (1968), Swain (1998), and this trend, if not the sole creator of Crainer (1998). We suspect the it. While an on-line magazine latter would not have included published by the University of Machiavelli if it had not been for Chicago says it offers a digest of the impact of Jay’s book. George’s the book. inclusion seems to be independent (http://magazine.uchicago.edu/102/ of Jay’s influence both by timing features/read2.html). The book is and by content. also recognized in the academic Fourth, is the flood of world. An online course subsequent works enfolding description at Indiana University Machiavelli into the embrace of refers to Management and business, commerce, and Machiavelli as a classic management taken broadly and in (http://www.indiana.edu/~deanfac/ combination. Included are: blspr03/hon/hon_h20_9199.html9). Calhoon (1969), Buskirk (1974), 8 Brahmsedt (1986), Funk (1986), Legge (1991), Griffin (1991), Johnson (1996), McAlpine (1997), Wren (1998), Bing (2000), Gunlicks (2000), Hill (2000), Borger (2002), Demack (2002), DiVanna (2003), Galie (2006), Diehl (2007), Harris (2007), Demack (2008), and Marsh (2009). These works are mostly trade books, though some are journal articles. Some mention Jay and some do not. Calhoon (1969) in the pages of the authoritative Academy of Management does, but Funk (1986) says “nothing has been written I have read restating, in current terms, the concepts expressed by Machiavelli” (vii), this twenty years after the first publication of Jay’s book. This list includes the more substantial works available but it is by no means comprehensive. We have then established that Jay’s Management and Machiavelli proved to be the first of a rapidly increasing number of works that claimed to apply Machiavelli to management. The impact of Jay’s book was in no way impaired by the very critical review Chris Argyris gave of it in Administrative Science Quarterly (1968). Argyris acknowledged the creativity, wit, and engaging style of the author, and so do we, but noted that it relied on a few anecdotes and hearsay. Its prescriptions were inconsistent where they were not too vague to understand. Reviews in popular business publications were and still are far more positive and the book has indeed been a success. It is now routinely accorded the status of classic. Prior to Jay’s book, Machiavelli was seldom if ever mentioned in the study and practice of management. There are two exceptions. During World War II Aimee Buchanan published The Lady means business: How to reach the top in the business world – the career woman’s own Machiavelli in 1942. The reference to Machiavelli appears on the title page and the dust jacket. Machiavelli is discussed nowhere in the text but each chapter ends with an epigram from his works. The book is a very sensible work of advice to girls and young women of the time who wish to pursue a career in business. It offers no shortcuts and promises no effortless remedies in contrast to so many self help books and morning television shows today. It boasts of no special insights and frequently recommends industry, hard work, and thoroughness together with a clarity of purpose as the best way to succeed. This advice is so patently sound it takes no Machiavelli to second it. Yet there is his name. It is altogether much more sane and modest than many titles in the flood of books since Antony Jay disinterred Machiavelli. Despite the merits of the book, why Machiavelli is mentioned remains a mystery to these readers. Claude George’s study The history of management thought (1968, pp. 42-45) includes about five pages on Machiavelli’s analysis of leadership, with comments on how that relates to organizations. No effort is made to press Machiavelli into service as a guide to contemporary practice, but he is treated as a sometimes systematic and always insightful observer of the working of individuals, organizations and 9 institutions. Given its publication date, a year after of the first edition of Management and Machiavelli, its sober tone, and the absence of any reference to Jay, we infer that George’s inclusion of Machiavelli was not influenced by Jay.i Having found few authoritative works about management, Antony Jay says that when reading Machiavelli’s The Prince he saw the relevance of much of what Machiavelli discussed to the contemporary business world. That led him to reflect on the nature of research and writing about business and management, which he found to be unrealistic and, at times, impractical, “fact-free,” he says. In Machiavelli he found an antidote to this. He puts it this way, ‘I have called this book Management and Machiavelli not because it is based on Machiavelli’s arguments but because it is based on his method, the method of taking a current problem and then examining it in a practical way in the light of experiences of others who have faced a similar problem in the past’ (Jay 1994, 28, emphasis added). Many who followed Jay have also taken the Machiavellian method, but some have also based their books on Machiavelli’s arguments, as shall see. Like many others, Jay supposes that Machiavelli called “his book The Prince because he saw the success or failure of states to stem directly the from the qualities of the leader” (Jay 1994, 29). Since Machiavelli did not publish The Prince and there is no evidence that he tried to do, we can never know his intentions, but his manuscript was not originally styled Il Principe but rather De Principatibus, “Of Principalities,” a title that better captures the overview of types of principalities in the book (see Richardson 1979). Jay is just one of many writers who makes a point about the title, which Machiavelli did not choose. After this discussion of Machiavelli’s method, he is not mentioned again in the remaining 200+ pages of Management and Machiavelli. 2. What do management writers take from Machiavelli? Two major themes underwrite Machiavelli’s service to the management and allied literature. (1) That the world of Machiavelli is like our world and vice versa: F = M. Conclusions drawn in one world apply to the other with little or no qualification. (2) The politics of Machiavelli’s world is just like business today, or enough like it to make him a guide. (1) If Machiavelli’s world is ours, then advice given in his world of 15th -16th Century Italian cities applies equally to our world. (This is, by the way, an assumption Machiavelli himself made explicitly. In his hand it goes something like this. Men make history and the nature of man is invariant. Lessons derived from examples of the Roman republic are then relevant in his Renaissance world. However, few contributors to the management literature cite Machiavelli to justify the equation of his world to ours.) At times this equation of the 15th and 16th Centuries with the 20th and 21st Centuries is simply assumed (Bing p. 1 and Diehl p 20). No explanation or justification is offered, but Machiavelli’s is evoked, and the only plausible 10 assumption is that is because it is regarded as relevant, and also as authoritative, the one wrapped inside the other. In 1969 Richard Calhoon said that the pressures differ in a corporation from a Renaissance city state but only in severity, not in kind (p. 210). (Calhoon cites Jay extensively though Management and Machiavelli had appeared only two years before.) Richard H. Buskirk in his book Modern Management & Machiavelli (1974), ‘I suggest that Machiavelli’s basic advice is not only applicable to the ruling of a state but is also germane to the problems of managing any organization’ (p. xxi). This book is noteworthy for two reasons. One, it makes no mention of Antony Jay’s Management and Machiavelli and, two, it cites not only The Prince but also the Discourses. Most of the mediums who channel Machiavelli into management see only the Prince in his resumé. Richard D. Funk in his book The Corporate Prince: Machiavelli Reviewed for Today (1986) writes that “Machiavelli’s Prince needed to be reexamined in order to establish a better understanding of his modes and orders for the corporate executive’. He goes on to say in the preface that “Nothing has been written I have read restating in current terms, the concepts expressed by Niccolò Machiavelli, 1469-1527” (p vii). This remark came nearly twenty years after Antony Jay’s Management and Machiavelli. Either Funk did not read Jay or found that by 1986 his work was no longer current. Or perhaps it is that he concentrates on Machiavelli's arguments rather than his method, as did Jay. In any case the publisher apparently agreed with Funk. Stuart Crainer in his compendium The Ultimate Business Guru Book: 50 thinkers who made Management (1998), says that Machiavelli advises that a prince think only about war and then that ‘corporate life is about power,’ citing Peter Drucker (p. 136). Thus does one guru affirm the merits of another, in this case Drucker confirms Machiavelli’s relevance. Gerald R. Griffin continues the emphasis on power, titling his book Machiavelli on Management: Playing and Winning the Corporate Power Game (1991). He says that Machiavelli is as applicable today as his work was in his own day (p. ix). Alistair McAlpine’s book The New Machiavelli: Renaissance realpolitik for Modern Managers (1997) claims to translate Machiavelli into contemporary business (p 8). This is the same McAlpine who had a very successful business career, and who served as the Treasurer and Deputy Chairman of the British Conservative Party before ascending to the House of Lords. The book shows a real sense of Machiavelli’s distinctiveness and is quite reflective, but it nonetheless presses Machiavelli into the service of contemporary business. The book is to some extent a companion piece to McAlpine’s earlier The Servant (1992)which emphasizes loyalty to a visionary leader, in his case that was Margaret Thatcher. The theme of power is continued in Ian Demack’s book The Modern Machiavelli: The Seven Principles of Power in 11 Business (2002) and in his related article in Forbes magazine (2008). In the book Demack says at the outset that “Machiavelli understood power” and that is what business is about (p. x). Ernest Buttery and Ewa Richter (2003) note the growing spate of references to Machiavelli and write that “Machiavelli’s principles are deemed to be applicable to our modern enterprises and have been said to offer critical advice to, and decisive discourse on, management thought and education” (p. 1). They give no reason for doubting that such deeming is sensible and then go on to add to it by applying Machiavelli’s so-called principles to assorted business matters. In Thinking beyond Technology: Creating New Value in Business (2003), Joseph Divanna writes that “Machiavelli talks about a prince and principalities, as we, in modern terms, talk about CEOs and corporation…. Machiavelli’s observations of how a principality is formed, governed, and ruled can be applied to modern merger and acquisition strategies’ (p. 113). In other books Machiavelli is in the title but is hardly in the text (Mervil 1980). With reference to career management, B. Jill Carroll (2004), writes that “Machiavelli’s famous book The Prince is one of the most provocative strategy manuals ever written” (p 1). This is an oft repeated point and perhaps it is time to say that the book known as The Prince has much in it aside from strategy and has an intelligence seldom seen in manuals. David McGuire and Kate Hutchings write in the Journal of Organizational Change Management (2006)that “Machiavelli’s … world has much in common with the modern … business world that is also beset by change, turmoil and challenges to the status quo” (p. 192). When probed, we suggest this similarity loses air quickly. Stanley Bing’s What Would Machiavelli do? The End justifies the Meanness (2000) is a benchmark in this literature. Bing, nom de plume for a Fortune journalist, is a much-published author. The book is so simpleminded and exaggerated one might even think it a parody except there is no evidence of humour or modesty in the author’s voice. Throughout this short book Bing distorts Machiavelli in the way some have done to Karl Marx. The result is a vulgar Machiavellianism. Bing freely dots factual errors along the way. He answers the title question by saying Machiavelli would lie, cheat, murder, steal, assassinate, kidnap, thieve and so on, and on, and on. This from a book that describes Saddam Hussein of Iraq as a successful Machiavellian (p. 64). The cover design of his book is a shark’s fin, calling on our primal fears of the vasty deep. In his rush to assert that Machiavelli recommended every sort of crime, calumny, misdeed, felony, transgression, and sin, Bing seldom pauses to refer specifically to any of Machiavelli’s words. One of the theses Bing dwells on is Machiavelli’s alleged recommendation to be amoral. Bing does not mean amoral in the sense of being detached, neutral, and impartial but rather he means 12 immoral (p 29 and 177). Others have recommended what they term Machiavellian amorality, though not always with the enthusiasm and carelessness of What would Machiavelli do? (Error is no bar to success and this book is now available in audio form from Audible.) Two examples suffice, Borger (2002, p. 1) and Gunlicks (2002, p. 22). As the subtitle of his book says, Bing sees in Machiavelli an open-ended justification of all actions as means to ends. In the case of What would Machiavelli do? the end is personal aggrandizement which Bing calls power (p. 29, 30, 77, 117, and more). This in a book that cites Pol Pot as an example of a Machiavellian ruler (p. 32). If this be jest, it is so offensive as to defy words of reproach. Others have also seen in Machiavelli a recipe for power of some kind, though none as crudely as in Bing’s book (Michael Korada 1975, p. 197; Michael Shea 1988, p. 8; Bartlett 1998, p v, Griffin 1991, p. viii, V [Curtis Johnson] 1996, p. xiii, Sheila Marsh 2009, p. 65, and Greene 2000, p. xvii ff, Pfeffer 201, p. 87). (2) Business is Politics by another name, or B = P. Antony Jay said it first and best, when he said that ‘Management is the great new preoccupation of the Western world. General Motors has a greater revenue than any state in the union … The giant corporations have far bigger revenues than the governments of most countries’ (p 2). He then opines that in the face of the vast number of books on management, ‘The new science of management is in fact only a continuation of the old art of government, and when you study management theory side by side with political theory, and management case histories side by side with political history, you realize that you are only studying two very similar branches of the same subject. Each illuminates the other…’ (p 3). Continuing he said that reading Machiavelli brought this truth home to him, yet Machiavelli is not at the moment [1967] required reading in business colleges or for management training courses’ (p. 4). (That has certainly changed, for web searching in business programs reveals many references to Machiavelli, though it may be they are all to such sources as those discussed here and not Machiavelli’s own works. Jay’s book does appear on the syllabi for some MBA courses that we have seen.) Jay also claims that ‘In all important ways, states and corporations are the same…. States and corporations can be defined in almost exactly the same way” institutions for the effective employment of resources and power… The competition of commercial and industrial rivals strikes, the problem of getting the most advantageous trading situation with least possible sacrifice of independence - all these problems are in their essence the same as enemy invasion, civil rebellion, or alliances with other states that have common interest or a common enemy’ (p. 13). Politics is business is politics. George writes in his The history of management thought (1968) that “the principles of 13 leadership and power that occupied Machiavelli are applicable to almost every endeavor which is organized and purposeful. Were he writing today he would probably be analyzing the power structure of our large corporations …” (p. 43). But George does not do so, but his text invite others to do so, and they did. Richard Calhoon's article in the Academy of Management Journal (1969), a very important research journal in management, a year later however cites Jay extensively and concludes that “Machiavelli would applaud the widespread application of his precepts to leadership in today’s organizations” (p. 205). Machiavelli’s applause indicates his imputed satisfaction in seeing his advice heeded. One of the most common tropes among those Machiavelli avatars in the business literature is to rewrite The Prince, following his chapters and changing or adding to the content to focus on commerce. Alistair McAlpine’s The New Machiavelli: Renaissance realpolitik for Modern Managers is one instance of this approach. Others are Richard Hill, The Boss; W. T. Brahmstedt, Memo to the Boss, Richard Funks, The Corporate Prince, Ian Demack, The Modern Machiavelli: The Seven Principles of Power in Business, and Alan Bartlett, Profile of the Entrepreneur, or Machiavellian Management. Some are even more subtle and put the word ‘prince’ in the title but do not mention Machiavelli when discussing business, e.g., Aquarius, The corporate prince: A handbook of administrative tactics (1971) in little more than one hundred pages of elegant and snappy text. These books invariably apply Machiavelli’s comments on the acquisition of lands to corporate mergers and acquisitions. Others who make this comparison include Crainer (1998, p. 136) and DiVanna (2003, p. 144). Richard Griffin’s Machiavelli on Management: Playing and Winning the Corporate Power Game (1991) parallels the manager to prince in an organization (p. 20), while John Legge’s The Modern Machiavelli : the nature of modern business strategy (1991) recommends the methods described by Machiavelli as somewhat appropriate to the way to run most types of business ( p. 1). This note of caution is a rarity in the rush to make Machiavelli a manager. Lynn Gunlicks justifies the title The Machiavellian Manager's Handbook for Success (2000) by saying that Machiavelli wrote for princes and while capitalist robber barons are not princes, this book is about them (p. xv). In The Boss: Machiavelli on managerial leadership (2000) Richard Hill writes that ‘The little book the Prince has a lot about leadership in it, especially for business leadership (pp. 6-7). Michael Thomas in the European journal of marketing (2000) compares Machiavelli’s advice and marketing (p. 524). The Corporate prince: Machiavelli's timeless advice adapted for the modern CEO (2002) by Henry Borger we read that the prince is equivalent to any autocratic ruler like a CEO (p. 2) and like the princes of old, CEOs live and work in a highly 14 competitive world (p. 4). Writing in the Journal of Management History Neil Hartley (2006) concludes that “Machiavelli was one of the earliest to conceptualize management/human nature in his most well known work The Prince” and so is a foundation of management study (p. 281). In Niccolo Machiavelli's The prince : a 52 brilliant ideas interpretation (2008) Tim Phillips has it that ‘the prince is closer in nature to a modern CEO than a prime minister’ (p. 3). For his part Midas Jones says Machiavelli’s advice should be heeded by all who work in organizations in his The Modern Prince: Better Living Through Machiavellianism (2008). In short there are many students of management, commerce, and business who have embraced Machiavelli and commend him and his works. They do so on two grounds. First that his reality is our reality, or at least it does not differ in significant ways, though some of the more careful authors like Alistair McAlpine do recognize important differences in the constraints on arbitrary power when he writes that ‘clearly, it is not possible at the turn of the twentieth century to behead a managing director’ (1997 p 28); he leaves aside whether it would be desirable. Jay notes that ‘of course, there are certain superficial differences’ between corporations and states’ (p. 14, emphasis added). Most who have followed him on Machiavelli road have not even paused to make that qualification, but rather have concluded that any similarity, e.g., a competitive environment, legitimates complete assimilation. It would follow, for example, that since athletes are competitive, they, too, should look to the pages of Machiavelli. But wait, that leap has already been made by Simon Ramo in Tennis by Machiavelli (1984). 3. Are Machiavelli’s time ours? Is business but politics by another name? Against both these propositions we suggest a more restrained approach is best. While Machiavelli’s insights are many and conveyed in diamond-bright prose, unencumbered by qualification, they do presume a context. That context in gross is that constant conflict among European powers in Italy. France, Spain, Venice, and Germany (in the form of the Holy Roman Empire) fought their dynastic and border wars almost constantly in Italy. The politics that Machiavelli experienced was nothing at all like business, modern or otherwise. It was cutthroat, it was capricious, it was blood red in fact not in metaphor. Only people who have never see it, can speak lightly of blood on the floor of a meeting room. To find similar environments today one would be well advised to look to failed and failing states like Pakistan, Iraq, or Afghanistan (McGrane 2011). Anyone who thinks corporate competition is like war has never experienced war. How the acquisition of Disney Studios by Sony Japan is like Cesare Borgia’s march through Romagna is beyond us, perhaps because so little do we understand the world of big business. But we do know what Borgia did, and little of it would be legal in any country 15 today. Nor was Machiavelli’s reality continuous with ours. To say that it is obliterates hundreds of years of European history in which concepts and practices of rights and justice, unknown to Machiavelli or any of his contemporaries, have developed, transmuted, and embedded themselves in our practices, our institutions, our conventions, and our minds. Ours is much more a government and politics of laws than of princes than anything Machiavelli could have foreseen. Indeed one suspects that the life of a CEO in business is bounded, limited, and constrained, too, and perhaps the fantasy that one can rise above that is part of the appeal of these books that bring Machiavelli and the shadow of his reputation into the world of business. We suggest that the value of Machiavelli is as a sounding board for one’s own reflections. He might be read in the same way one reads Plutarch’s Lives or the Homer’s Iliad, for examples to react to, rather than models to follow or to codify into a manual. Human nature may be a constant, as Machiavelli himself supposed, but if it remains the same, it also changes. Dropped down in a jungle, perhaps a person off the street today might well soon behave as a 15th or 16th Century Florentine in the same situation would, but, outside reality television, we do not live in jungles, but in civilizations that shape and constrain us. As some of the books that Glendower-like summon Machiavelli from the vasty deep in their titles, do not thereafter mention him, others make the barest mention, and then proceed to offer their own accounts cloaked by Machiavelli’s imagined authority. Yet some of these works do explicitly borrow from Machiavelli and apply specific tenets from his works, almost invariably, but not quite exclusively, The Prince. Antony Jay himself, whom we credit with creating Machiavelli 'The sage of management,' refers to Machiavelli only in the first thirty pages of his book. There his argument, largely anecdotal, is that the management books he read idealized management and counselled high-minded, hyper rational approaches, which seemed far from the reality of business as he knew it. He asked a few people he met, including some by chance in elevators, if we are to believe what we read, and they agreed with him (1967, p. 4). (We almost always agree with people who accost us in elevators! We then exit at the next floor.) In contrast to this rational, sanitized, vision of business, Jay saw a confused, conflicted, inconsistent reality that reminded him of what he had read in Machiavelli. The page he then decided to take from Machiavelli’s book was the method page: namely, an accurate description of the reality is the foundation for any conclusions or recommendations. Jay says it in this way: ‘I have called this book Management and Machiavelli not because it is based on Machiavelli’s arguments but because it is based on his method, the method of taking a current problem and then examining it in a practical way in the light of experiences of others who have 16 faced a similar problem in the past’ (p. 28). It is not just any method, then but the method of realism. Others have credited Machiavelli with this title, Realist, too. They include James Burnham (1943) and any number of international relations theorists seeking patrimony for the doctrine of that name in that field. Others have followed Jay in claiming that Machiavelli’s method of realism is what they recommend (Wren 1998, p. 192; Carter 2002, p. 7; Buttery 2003, p. 432; Carroll 2004, p. 6; and Diehl 2007, p. 29). Few have ever recommended unrealism. While there is much reality in all of Machiavelli’s works, there is also much else. We wonder if those who so readily grant him the title Realist really agree with him that Roman Republican history holds answers for his time and place and all others. We wonder if they would see realism in Machiavelli’s rejection of artillery and fortifications in favour of citizen militias. At times in his overheated pages of the Art of War the serried ranks of citizens, bare-chested before an enemy’s cannon seems to be the real test of the moral fiber of a community. We wonder if those who find in Machiavelli the realist’s eye would agree with his closing paean in The Prince for Lady Italy? Or do we conclude that proclaimed realists are but disappointed romantics? Finally, how would those who urge Machiavelli’s example, especially in managing one’s own career, square the praise they heap on him with Machiavelli’s dismal failure in his career. His curriculum vitae is far from impressive for one so credited with a mastery of tradecraft. He did a great deal of work (the hardest, the most gruelling, and the riskiest assignments that no one else wanted), it is true, but he failed ever to get promotion, commensurate pay raises, or a transfer to a more secure post. When the regime changed he was caught by surprise and had no escape plan for himself. He was one of only two in the chancellery terminated immediately when the regime changed. He made only half-hearted efforts to re-start his career, preferring to wait for his call to greatness in Florence; it did not come. When offered a sinecure in Rome, he rejected it to wait for that call among bumpkins in the hills. As to this latter point, most of the authors who cite him, we suspect, would have advised him to relocate and restart his career, the better to return at a later time to Florence, if that is what he wished. One can only image the advice a self-help guru like Depak Chopta would have given him! 4. To conclude One of the most amusing features of the purveyors of Machiavelli’s reliquary maxims is the fervor which these authors tell us Machiavelli speaks directly to us but that to hear his voice we need to read their books not his. This is the perfectly squared circle. On the one hand, Machiavelli’s books, usually but not always just The Prince, offers us clear and penetrating insights into the contemporary world of business. On the other hand, his message is garbled enough to need translation by the author. Vanity, thy name is on the dust jacket. Richard Buskirk (1974, p. xxi) says he presents Machiavelli's 17 ‘actual words in context’ through extensive quotations’ and omits 'from the Prince and Discourses material not relevant to the management of men.’ We are left with a cut-down version The Prince embellished by Buskirk’s own offerings. A decade later Funk (1986. p. vii) wrote that 'Machiavelli's The Prince needed to be reexamined in order to establish a better understanding of his modes and orders for the corporate executive (or Prince). Here we see some acknowledgement that Machiavelli and The Prince stand at some remove of the contemporary word, but that seems only a matter of accent, as when Spanish and Portuguese speakers communicate. Griffin (1991, p. xv) says simply that we cannot just read Machiavelli because his books were written in a 16th Century context.’ No indeed, we have to think. But none of these writers of this self-promoting bunk can top Stanley Bing (2000, p. xviii) who says, ‘Nobody can really understand Machiavelli’s actual writing today, however, because it is too literate, too grounded in meaningless social, political, military anecdote, to remain interesting to anyone with normal intelligence, attention span, and patience.’ With these quick keystrokes he dismisses most of what Machiavelli thought was important. He goes on to add ‘lacking an ability to read Machiavelli, people … need books like this one to explain how his teaching can help…to become powerful and rich.’ Chronology leaves the last word to Ian Demack (2002, p. x) who says: ‘The Prince remains as relevant and provocative today as it was in 1513. But many find it difficult to read.’ We are willing to concede that possibility if Demack is willing to concede that the empirical assertion needs evidence. For ourselves there are few writers more trenchant than Machiavelli which is why he is so often quoted, out of context. Above we referred to factual errors. Chief among this is the misrepresentation of Machiavelli’s working life. On this point, too, Bing’s What would Machiavelli do? is the outstanding example. Consider this unqualified assertion, Machiavelli ‘was a mid-level bureaucrat who for the best part of his career worked’ and reported ‘to the Prince of Florence’ (p. xx). Machiavelli’s political career was in service to the republican government led by Piero Sorderini. Machiavelli never worked for a prince. Period. It follows that it is equally mistaken to refer to his alleged efforts to gain reinstatement at court and still more silly to say that ‘Medici liked what he read, exercised a full measure of executive amnesia, and Machiavelli … was welcomed back to a nice corner office will full honors. His fame has only grown in the years since’ (ibid.). Those familiar with the broad outlines of Machiavelli’s life and his exile from Florence will know how erroneous these remarks are, but this is no the place to correct those errors, though noting them does indicate how carelessly Machiavelli is treated by those who take his name in vain. In conclusion it must be said that a very few others have noted the need for caution in integrating 18 Machiavelli into the management pantheon. Michael Macaulay and Alan Lawton (2003) apply a speed camera to slow down the rush to make Machiavelli into something he was not, as does John Swain (2002) and Buttery and Ewa (2003). We differ in that our survey is much more comprehensive and our critique of the spectre of Machiavelli in management is likewise more thoroughgoing. References The twelve English translations and editions of The Prince consulted. Leo Paul de Alvarez, The Prince (Prospect Heights, Ill: Waveland, 1989). James Atkinson, The Prince (New York: Macmillan, 1985). George Bull, The Prince (Middlesex: Penguin, 1961). Peter Constantine, The Prince (London: Vintage, 2009). Daniel Donno, The Prince (New York: Bantam, 1981). Christian Gauss, The Prince (New York: Mentor, 1952). Harvey Mansfield, The Prince (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985). W. K. Marriott, Re:Organizing America: A Plan for the 21st Century: Nicolo Machiavelli's the Prince (CreatSpace 2010). Rob McMahon, ed., Machiavelli's the Prince: Bold-Faced Principles on Tactics, Power, and Politics (Sterling 2008). Cary Nederman, The Prince; on the Art of Power, the New Illustrated Edition of the Renaissance Masterpiece on Leadership (London: Duncan Baird, 2007). Brian Richardson, Il Principe (Oxford, England: Alden Press, 1979). Quentin Skinner and Russell Price, The Prince (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988). Authoritative references in the History of Political Thought consulted. William T. Bluhm, Theories of the Political System: Classics of Political Thought & Modern Political Analysis, Third ed. (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc. , 1978). J. H. Burns and Mark Goldie, eds., The Cambridge History of Political Thought, 1450-1700 (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1991). John Dryzek, Bonnie Honig, and Anne Phillips, eds., The Oxford Handbook of Political Theory (Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2006). William Ebenstein and Alan O. Ebenstein, Great Political Thinkers: Plato to the Present (Fort Worth, TX: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1999). Bruce Haddock, A History of Political Thought (Cambridge, England: Polity, 2008). George Klosko, ed., The Oxford Handbook of the History of Political Philosophy (Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2011). 19 J. S. McClelland, A History of Western Political Thought (London: Routledge, 1998). Cary Nederman, "Niccolò Machiavelli," Stanford University Press, http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/machiavelli/. Retrieved 4 July 2011. John Plamenatz and Robert Wokler, Man & Society: Political and Social Theories from Machiavelli to Marx, Three vols., vol. One (New York City: Longmans, 1992). George Sabine and T. L. Thorson, A History of Political Theory, Fourth ed. (Hinsdale, Ill.: Dryden, 1993). Leo Stauss and Joseph Cropsey, History of Political Philosophy, Third edition ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987). Sheldon Wolin, Politics and Vision: Continuity and Innovation in Western Political Thought, Expanded ed. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006). Machiavelli and management Aquarius, Qass. The Corporate Prince: A Handbook of Administrative Tactics. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Co 1971. Argyris, Chris. "Review of Management and Machiavelli by Antony Jay." Administrative Science Quarterly 13, no. 1 (1968): 1890182. Bartlett, Alan F. Profile of the Entrepreneur, or Machiavellian Management. Sheffield: Ashford Press, 1988. Bing, Stanley. What Would Machiavelli Do? The Ends Justify the Meanness. New York: HarperCollins, 2000. Borger, Henry. The Corporate Prince: Machiavelli's Timeless Advice Adapted for the Modern CEO: Authorhouse 2002. Brahmstedt, W. T. Memo. To: The Boss From: Mack: A Contemporary Rendering of the Prince by Niccolo Machiavelli. Palm Springs, California: ETC Publications, 1986. Buchanan, Aimee. The Lady Means Business: How to Reach the Top in the Business World, the Career Woman's Own Machiavelli, 1942. Burnham, James. The Machiavellians: Defenders of Freedom. Chicago: Henry Regnery, 1943. ———. The Managerial Revolution or What Is Happening in the World Now. London: Putnam, 1941. Burns, J. H., and Mark Goldie, eds. The Cambridge History of Political Thought: 1450-1700. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991. Buskirk, Richard. Modern Management & Machiavelli: The Executive's Guide to the Psychology and Politics of Power. New York City: New American Library, 1974. Buttery, Ernest, and Ewa Richter. "On Machiavellian Management." Leadership & Organization Development Journal (2003). Calhoon, Richard. "Niccolo Machiavelli and the Twentieth Century Administrator." Academy of Management Journal 12, no. 2 (1969): 205-12. Carroll, B. Jill. Machiavelli for Adjuncts: Six Lessons in Power for the Disempowered: Aventine Press, 2004. 20 Carter, Terrell. Machiavellian Arts Management: 21st Century Advice for Contemporary Arts Managers. St Louis, MO: CCD Publishing, 2002. Crainer, Stuart. The Ultimate Business Guru Book : 50 Thinkers Who Made Management. Oxford: Capstone, 1998. Demack, Ian. The Modern Machiavelli: The Seven Principles of Power in Business. Sydney: Allen and Unwin, 2002. Diehl, Daniel. Management Secrets from History: Historical Wisdom for Modern Business: Sun Tzu, Machiavelli, H. J. Heinz, Elizabeth I, Confucius. Stroud: Sutton, 2007. DiVanna, Joseph. Thinking Beyond Technology: Creating New Value in Business. London: Palgrave, 2003. Dryzak, John, Bonnie Honig, and Ann Phillips, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Political Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006. Funk, Richard D. The Corporate Prince: Machiavelli Reviewed for Today. : Vantage Press, 1986. George, Claude S. The History of Management Thought. Engelwood Cliffs, N. J.: Prentice-Hall, 1968 Goodin, Robert, and Hans-Dieter Klingmann. A New Handbook on Political Science. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996. Griffin, Gerald R. Machiavelli on Management: Playing and Winning the Corporate Power Game. New York City: Prager, 1991. Gunlicks, Lynn. The Machiavellian Manager's Handbook for Success iUniverse 2000. Hartley, Neil. "Management and History." Journal of Management History 12, no. 3 (2006): 278-92. Herring, Hubert B. "Business Authors Bring Machiavelli Back to Life." The Globe and Mail (Index-only) 1999, M2-0. Hill, Richard. The Boss: Machiavelli on Managerial Leadership. Geneva, Switzerland: Pyramid Media Group, 2000. Jay, Antony. Management and Machiavelli; Discovering a New Science of Managment in the Timeless Principles of Statecraft London Hodder and Stoughton, 1994 (1967). Johnson), V. (Curtis L. The Mafia Manager: A Guide to the Corporate Machiavelli. New York City: St Martin's, 1996 (1991). Korda, Michael. Power: How to Get It. How to Use It. New York City: Ballantine 1975 Legge, John. The Modern Machiavelli : The Nature of Modern Business Strategy [Hawthorn, Vic.: Swinburne College Press], 1991. Macaulay, Michael, and Alan Lawton. "Misunderstanding Machiavelli in Management: Metaphor, Analogy and Historical Method." Philosophy of Management 3, no. 3 (2003): 17-30. McAlpine, Alistair. The New Machiavelli: Renaissance Realpolitik for Modern Managers. London: Aurum, 1997. ———. The Servant. London: Faber and Faber, 1992. McGrane, Christopher. "Is Machiavelli's the Prince Still Relevant in the 21st Century?" In Australian Political Studies Association. Melbourne, 2010. 21 Mervil, Fritz Lawrence. The Political Philosophy of Niccolo Machiavelli as It Applies to Politics, the Management of the Firm, and the Science of Living: American Classical College Press, 1980. Najemy, John, ed. Cambridge Companion to Machiavelli. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010. Pfeffer, Jeffrey. Power: Why Some People have it and Others don’t. New York City: HarperBusiness, 2010. Phillips, Tim. Niccolo Machiavelli's the Prince : A 52 Brilliant Ideas Interpretation. Warriewood, N.S.W.: Woodslane, 2008. Price, Russell. "Machiavelli. Niccolo." In International Encyclopaedia of Business and Management, edited by Malcolm Warner, 2607-13. London: Routledge, 1996. Ringer, Robert. Winning through Intimidation. Second ed. New York City: Funk & Wagnalls, 1973. Shea, Michael. Influence: How to Make the System Work for You. A Handbook for the Modern Machiavellian. London: Century, 1988. Swain, John. "Machiavelli and Modern Management." Management Decision 40, no. 3 (2002): 281-87. Witzel, Morgen. "Niccolo Machiavelli." In Fifty Key Figures in Management, edited by Morgen Wizel, 194-98. London: Routledge, 2003. Wren, Daniel, and Ronald G. Greenwood. Management Innovators: The People and Ideas That Have Shaped Modern Business. New York City: Oxford University Press, 1998. i That remarkable scholar James Burnham published two books that are sometimes conflated. In 1941 he published The Managerial Revolution or What is Happening in the World Now and in 1943 The Machiavellians: Defenders of Freedom. The former argues that the post-war world will be dominated by those that manage large organizations, be they government, military, business, or labour, rather than by those that own them. It is a sociological study of the origins of such a management class. The latter title is a study of realism in political analysis wherein Burnham gives Machiavelli pride of place, for his self-professed and largely realized aspiration in The Prince to examine what is done, how and why it is done, rather than to dwell on what should be done. Machiavelli is not mentioned in the text of The Managerial Revolution and managers are not mentioned in The Machiavellians. Though sometimes it is assumed otherwise.