Sly Indoctrination: British and American

advertisement

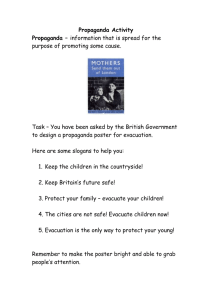

1 Sly Indoctrination: British and American Propaganda in World War I and It’s Effects on America’s German Element Elizabeth Ortel Historical Paper Senior Division 2 The night before his 1917 war message to Congress, Woodrow Wilson said that, “Once led into war, our people will forget that there ever was such a thing as tolerance…”1 This comment from the pacifist president who “kept us out of war” marked a huge shift in American popular opinion that was caused by the British propaganda machine. Throughout World War I, British anti-German sentiment was communicated through atrocity-based propaganda that was understood and embraced by Americans, who began to believe that Germans, whether United States citizens or Europeans, were the enemy. When the major powers of Europe entered WWI in 1914, the United States pledged neutrality, resisting involvement in a distant conflict. However, despite this “neutrality”, there was an extreme growth of pro-Ally, anti-German sentiment. Much of this shift in American public opinion can be attributed to the British propaganda machine, run by the British War Propaganda Bureau (WPB).2 Established in 1914 by Chancellor of the Exchequer David Lloyd George, the WPB was based at Wellington House in London and placed under the control of Charles Masterman, a successful writer and Liberal Parliament member. The WPB became the major British propaganda distributor, both at home and abroad, especially to the United States. Popular British authors such as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Rudyard Kipling were hired to write pamphlets and books promoting Britain’s war interests, while major companies such as the Oxford University Press and Macmillan published WPB anti-German materials, including 1160 pamphlets with titles like The Barbarism in Berlin. The WPB appointed Canadian novelist and poet Sir Gilbert Parker to make sure that books by "extreme German nationalists, militarists, and 1 Thomas Fleming, The Illusion of Victory (New York: Basic Books, 2003), 6. Hereafter cited as Fleming, Illusion of Victory. 2 Robert A. Wells, “Mobilizing Public Support for War: An Analysis of American Propaganda During World War I,” International Studies Association New Orleans Archives, available from http://www.isanet.org/noarchive/robertwells.html; accessed 12 February 2004. Hereafter cited as Wells, “Analysis of American Propaganda”. 3 exponents of Machtpolitik such as von Treitschke, Nietzche, and Bernhardi" were published in the United States to skew perception of German authors.3 In addition, the WPB kept in close contact with American newspapers, received weekly reports on the state of American public opinion, and arranged interviews with prominent Englishmen to increase Britain’s likeability in the United States. In 1917, Charles Alfred Harmsworth (Lord Northcliffe) initiated the establishment of the British Bureau of Information in New York City, a symbol of the WPB’s influence in the United States.4 With a propaganda machine intact, the British implemented various measures to ensure worldwide dominance of their war views. In August 1914, a British ship, the Teleconia, deliberately cut Germany’s underwater communication cables, eliminating Berlin’s principal means of contacting the outside world. Now, with only Marconi’s wireless to send messages, British cryptanalysts could easily intercept and decipher German messages.5 Subsequently, the consul general of Germany’s ally Austria-Hungary told the New York Times: “The cutting of that cable may do us great injury. If only one side of the case is given…prejudice will be created against us here.”6 He was not mistaken. Soon after the cable cutting, Parliament passed the Defense of the Realm Act, which gave British censors the ability to dissect all information traveling from England to the world, and Britain was thus able to modify news and opinions traveling to the United States. With an effective propaganda machine, and tight control over news from Europe to the United States, Britain was able to influence American public and governmental opinion, thus nurturing a pro-Ally and anti-German stance in the United States. Jonathon A. Epstein, “German and English Propaganda in World War I,” New York Military Affairs Symposium, available from http://library automation.com/nymas/propagandapaper.html; accessed 16 May 2005. Machtpolitik means “power politics.” 4 Lord Northcliffe also owned the British newspaper, The Times. He was staunchly anti-German. 5 Barbara Tuchman, The Zimmerman Telegram, (New York: Ballantine, 1985), 10-11, in Fleming, Illusion of Victory, 44. 6 Stewart Halsey Ross, Propaganda for War: How the United States Was Conditioned to Fight the Great War of 1914-1918 (Jefferson, N.C., 1996), 27-28 in Fleming, Illusion of Victory, 45. 3 4 The British depended heavily on atrocity propaganda to sway American opinion. By popularizing and exaggerating German actions, Britain was easily able to arouse anti-German sentiment in Americans. Luckily for the British, Germany gave them many scandalous stories on which to build their propaganda. Britain’s first opportunity to spread anti-German sentiment arrived with Germany’s invasion of Belgium in August 1914. When the conflict began, Germany asked the Belgian government permission for safe passage for the German army, agreeing to pay for food obtained en route and damages to property. Although Belgian neighbor Luxembourg found these terms acceptable, Belgium did not, and maintained their terms of “neutrality.”7 In reality, Belgium had secret agreements with Britain and France, and therefore maintained a covert pro-Ally stance.8 Nevertheless, when the German army crossed into “neutral” Belgium in August of 1914, Germany, a “militaristic, imperialist giant” was harshly condemned for invading “poor little Belgium,” a small, neutral, democratic country.9 Consequently, British propagandists had a field day. Atrocity stories flooded into Allied nations, especially the United States, via Britain: there were eye-witness accounts of infantrymen spearing Belgian babies with their bayonets, boys with amputated hands and women with amputated breasts. Atrocity propaganda proliferated. Cartoons such as “Babes on Bayonets” showing German soldiers with babies hanging from their bayonets appeared in popular American magazines such as Life, and posters commanded Brits and Americans to “Remember Belgium” while they gazed on an image of a woman being dragged away by a German soldier (Appendix 1.1, 1.2). A group of Belgians was later sent at the expense of the British government to tour the United States recounting these stories of German atrocities. Strangely enough, in September 1914 when a group of American news 7 Fleming, Illusion of Victory, 50. Fleming, Illusion of Victory, 50. 9 Fleming, Illusion of Victory, 50. 8 5 reporters was permitted to follow the German army through Belgium, they sent a telegram to the Associated Press saying that the reports of atrocities were “groundless as far as [they were] able to observe.”10 To retain American sympathy for Belgium, the British had to add much needed legitimacy to the German atrocity claims in Belgium. To do so, the British government organized a royal commission to investigate the validity of the reports. They asked Viscount James Bryce, an admired and well-known scholar of the era, to head the commission, which analyzed 1,200 testimonies of anonymous eyewitnesses.11 The resulting Bryce Report was released in May 1915, and was immediately sent to American newspapers by Wellington House. The New York Times reported: “GERMAN ATROCITIES ARE PROVED, FINDS BRYCE COMMITTEE Not Only Individual Crimes, but Premeditated Slaughter in Belgium”12 The Bryce Report, essentially a piece of anti-German propaganda legitimized the idea that the Germans were a cruel “race” to be feared and garnered American sympathy for the Allied cause. Accordingly, America’s anti-German sentiment grew. The next anti-German propaganda bonanza for the WPB came with the sinking of British passenger liner the Lusitania on May 7, 1915. Of 2,000 passengers on board, 1,198 died 10 H.C. Peterson, Propaganda for War: The Campaign Against American Neutrality (Port Washington, N.Y., 1968), 55 in Fleming, Illusion of Victory, 52. 11 Fleming, Illusion of Victory, 53. 12 New York Times, May 13, 1915, quoted in Fleming, Illusion of Victory, 53. 6 including 128 Americans. Americans were outraged, and the British propagandists seized the opportunity to distribute more anti-German materials. Posters were released featuring a drowning woman and child with the message “ENLIST” (Appendix 2.1). Another poster depicted a sinking ship with hands grasping the water fronted by the goddess of war Minerva urging men to “TAKE UP THE SWORD OF JUSTICE” (Appendix 2.2). Propaganda materials following the Lusitania disaster further distorted the image of Germans into justifiable “Huns.” However, most never realized that the Lusitania had been carrying a wide array of contraband, and few acknowledged that Germany had posted notices in New York City warning that the Lusitania was a targeted ship. (Appendix 2.3).13 Further aiding the British propaganda efforts was the Germans’ execution of British nurse Edith Cavell in 1915 for helping some 200 Allied soldiers escape from occupied Belgium to Holland. Her story was widely publicized in Great Britain and the United States. Few events of the First World War, it seemed, had as much of an emotional impact on Americans as the execution of Nurse, or “Sister”, Cavell.14 Once again, the Germans became murderers. However, the major newspapers in Britain and the United States failed to report the execution of two German nurses by French soldiers that occurred several weeks later. The posters, pamphlets, and other forms of propaganda released by the WPB directly stemming from the invasion of Belgium, the sinking of the Lusitania, and the execution of Edith Cavell, filtered a sharp anti-German outlook into the United States. Although the United States was officially neutral during this time, most historians believe the impact of British war The Lusitania sinking occurred during the first period of Germany’s unrestricted submarine warfare from February 1915 to September 1915, drawing American attention to Germany’s seemingly barbaric U-Boat policies. 14 Wells, “American Propaganda.” Nurses were called “sisters” in Britain, leading some to believe Cavell was a nun, increasing the shock of her execution. 13 7 propaganda was substantial to change the opinions of many about Germans and German culture, including President Woodrow Wilson.15 However, by the time President Wilson gave his war message in 1917, most Americans continued to express uncertainty about entering the war, and did not particularly despise the Germans.16 To heighten American hatred towards the enemy and sympathy for the Allies, President Wilson summoned George Creel, a muckraking journalist, to head the multi-divisional Committee on Public Information (CPI), which turned out anti-German materials.17 Pamphlets titled, The German Whisper, German War Practice, and Conquest and Kultur were distributed, and Hollywood filmmakers manufactured pictures like The Wolves of Kultur, and The Kaiser: The Beast of Berlin. CPI-hired artists created illustrations advertising government liberty bonds portraying looming German “Huns” in the background. On the 1918 cover of The Rhino, a menacing Hun encroaches upon a wasteland with sword in hand, and a message reads, “Beat Back the HUN with LIBERTY BONDS” (Appendix 3.1).18 An ad for the Fourth Liberty Loan depicts an alarming German soldier looming over the White House (Appendix 3.2). Other German-bashing materials produced by the CPI included a poster proclaiming “DESTROY THIS MAD BRUTE, ENLIST” while a growling gorilla with a Prussian helmet manhandles a screaming woman, and a poster displaying a train with an American flag emblem speeding towards the Kaiser (Appendix 3.3, 3.4). By distributing these materials, the CPI became the attaché for the British cause in America. 15 Woodrow Wilson, War Messages, 65th Cong., 1st Sess., Senate Doc. No. 5, Serial No. 7624 (Washington, 1917), p. 3-8, passim, in Louis L. Snyder, Historic Documents of World War 1 (Princeton: Van Nostrand, 1958), 152-55. 16 Anti-German feeling was strongest among the upper classes on the Atlantic coast, and those with business connections to Britain or France. Aaron Delwiche, “Of Fraud and Force Fast Woven: Domestic Propaganda During The First World War,” First World War.Com; available from http://www.firstworldwar.com/features/propaganda.htm; accessed 13 February 2005. 17 The primary purpose of the CPI was to create nationwide support for the war. 18 The Rhino was a magazine. 8 Besides media materials, comments made by American politicians also signaled a shift in American opinion against Germany. As part of his campaign against hyphenated Americans, President Wilson made various remarks on the necessity of German-American loyalty. Theodore Roosevelt wrote in 1916, “The German-Americans who call themselves such…have shown that they are not Americans at all.”19 In 1917, former U.S. ambassador to Germany James W. Gerard said in a message to the Lady's Aid Society in New York that if any GermanAmericans were to aid the Kaiser, "there is only one thing to do with them. And that is to hogtie them, give them back the wooden shoes and the rags they landed in, and ship them back to the Fatherland."20 The German-Americans tried to stop this tide of anti-German propaganda from overcoming them. They set up a Literary Defense Center, which sponsored the books by American authors defending Germany and Austria-Hungary. German-born George Sylvester Viereck began the English-language weekly, Fatherland. The German-American Alliance organized meetings in Washington D.C. to peacefully demand an embargo on munitions sales to England and France. However, the Germanophobia produced by the British WPB and nurtured by the American CPI led many to consider the efforts by the German-American community to defend their homeland disloyal attempts to aid the enemy war effort. Germans had been living in the United States since the seventeenth century, and were considered one America’s most respectable, industrious, and economically accomplished immigrant groups. Germans had fought for the colonies in the Revolutionary War, and many 19 Theodore Roosevelt, Fear of God and Take Your Own Part (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1916), 279. Quoted in Nate Williams, “German-Americans in World War I.” Western Front Association, available from http://www.wfa-usa.org/new/germanamer.htm; accessed 7 Mar 2005. 20 James W. Gerard, “Loyalty and German-Americans” (oration at Brooklyn Academy of Music in New York City on 25 November 1917), Center for History and Media; available from http://chnm.gmu.edu/features/voices/wwIgerman/warongerman.html#; accessed 28 Mar 2005. 9 immigrants had long since been integrated into mainstream America.21 Ultimately, the German-Americans were an esteemed, loyal immigrant group in the eyes of most Americans. However, as a result of the extensive British propaganda defining Germans and their culture a menace to society, ultra-patriotic Americans and Anglophiles began to attack all aspects of German culture in their own country no matter how remote. These Germanophobes first attacked the one thing that bound all varieties of GermanAmericans together: their language. In 1910, there were approximately nine million Germanspeaking Americans. German-language communities were widespread, and many schools were devoted to German-language education. However, as soon as the war propaganda created a fear of German spies and insurrections in the United States, the German language began to be viewed as the language of the enemy, and attempts were made to discontinue its instruction. In 1917, Ohio and Louisiana both enacted measures outlawing teaching in German. In 1918, the Nebraska legislature revoked its Mockett Law, because opponents believed German was the only language benefited by the act.22 Eventually, all states required the exclusive use of English in all schools. Coinciding with the attacks on German-language education was an extreme decline in the subscriptions to German-language newspapers. Prior to WWI, the German-language press led all other foreign publications in the United States, but after war was declared in April 1917, subscriptions declined rapidly. In October 1917, Congress enacted a law demanding that all matters relating to the war be submitted to the local postmaster for censoring until the paper had 21 Although the most documented group of Germans in the Revolutionary war were the Hessians, who served as British mercenaries, many Americans of German ancestry simultaneously fought for American independence. 22 The Mockett Law was passed in 1913, and required every high school, city school, or metropolitan school to give instruction in modern European languages requested by at least fifty parents in grades four and above. La Vern J. Rippley, The German-Americans (Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1976), 124. 10 proved its loyalty.23 In 1894, there were over 800 German publications in the United States, but by 1920, there were only 278. Propaganda had increased the fear that German-language newspapers could serve as an organ for the Kaiser in America. As a matter of course, German-language churches were also condemned. Charges that German-Lutheran churches were "hotbeds of treason..." led to the disruption of services and the threatening of pastors.24 Major newspapers including the St. Louis Globe and The New York Times encouraged German-American churches to drop German language services. Many ministers fought these attacks, responding that their congregations would not be able to worship properly if services were in English. This was the response of Wisconsin minister Rev. R. Krenke after the Bayfield County Council of Defense complained that, "any attempt either to teach the German language to the children or to encourage the speaking of it is [considered] giving aid and comfort to the enemy."25 However, despite the efforts to save German language services, their numbers dropped profoundly as complaints from the community took their toll.26 Furthermore, many surnames and business names were anglicized to disguise German heritage. The National German American Bank in Wausau, Wisconsin, became the American National Bank of Wausau. Surnames were changed, for example, from Schwartz to its English translation Black and Lichtenberger to Gerry. Some anglicizations went humorously over the top. Sauerkraut was renamed “liberty cabbage,” wieners became hot dogs, and dachshunds became “liberty dogs.” In St. Louis, with a major population of German ancestry, Berlin Avenue 23 Only applied to foreign-language newspapers; German-language papers were targeted in particular. La Vern J. Rippley, The German-Americans (Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1976), 107. 25 Rev. R. Krenke to Gov. Emanuel L. Phillipp, October 21, 1918, Wisconsin History Online, available from http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/teachers/lessons/wwi/pdfs/expressionfullpackage.pdf; accessed 13 February 2005. 26 The Missouri Synod Statistical Yearbook stated that services in German had dropped from 62 percent in 1919 to 46 percent in 1926. 24 11 became Pershing Avenue, and Kaiser Street became Gresham Street. The entire town of Luxembourg, Missouri, was rechristened Lemay. "Patriotism" ran rampant. Unfortunately, various atrocities were also committed in the name of "patriotism." In some localities, German books and newspapers were burned, and orchestras dropped German pieces from their repertoires.27 Acts of violence occurred, the most infamous being the murder of German-born Robert Prager in April 1918. Seized by a drunken mob in Collinsville, Illinois, he was wrapped in the American flag, and lynched after being allowed to write a farewell letter to his parents in Germany. Although atrocities were condemned by the President, little could be done to halt dangerously patriotic people from acting in the name of “liberty.” During World War I, British propaganda was successfully used to sway America into a pro-Ally, anti-German stance. Communicating the necessity of the defense of liberty from a hostile enemy, the British propagandists led Americans to understand that a German victory in the war would threaten the ideals upon which their nation was founded. Unfortunately, the indirect victims of this propaganda included the Germans in America. Once a highly esteemed immigrant group, the paranoia stimulated by Germanophobic atrocity propaganda caused a severe repression of their language and culture. “Listening to WWI: The War at Home, The War on German Americans,” Center for History and New Media; available from http://chnm.gmu.edu/features/voices/ww1german/warongerman.html; accessed 14 February 2005. 27 12 Appendices 13 Appendix I 1.1 “Babes on Bayonets” from Life, 1915 1.2 “Remember Belgium” War Bond Poster, 1915 14 Appendix 2 2.1 British “Enlist” Poster, 1914-1918 2.2 “Take Up The Sword of Justice” Poster, 1914-1918. 2.3 Lusitania Warning 15 Appendix 3 3.1 “Beat Back the Hun” Strothmann, 1918 Rhino Cover 3.2 Government “Hun” Bond Ad, 1914-1918 3.3 “Destroy the Brute, Enlist”, Poster, 1915 3.4 “Keep ‘em Going!” McAdoo, Poster, 1917 16 Annotated Bibliography Primary Newspaper "Another Tar and Feather Party is Staged." Ashland Daily Press 11 Apr. 1918. 3 Dec. 2004 <http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/teachers/lessons/wwi/pdfs/expressionfullpackage.pdf> A period newspaper article, its subject is a man that was attacked for his alleged proGerman sentiments. The article was used to exemplify the many innocent people prosecuted because of wartime suspicion and paranoia. An original article photocopied, it is a primary source. Carnegie, Andrew. “Kaiser Wilhelm II., Peacemaker.” New York Times 8 June 1913: SM4. The New York Times. ProQuest Information and Learning. Lincoln High School Lib., Tallahassee, FL. 16 May 2005 <http://proquest.umi.com/login>. This is Andrew Carnegie’s article from 1913, before the beginning of WWI, praising the Kaiser’s progressive reforms in Germany, and his success in preserving peace in his country. Carnegie’s opinion in 1913 is far different from those that would infiltrate the United States in the following year. "'Damnable!' Says Sunday." New York Times 8 May 1915: 3. The New York Times. ProQuest Information and Learning. Lincoln High School Lib., Tallahassee, FL. 28 Mar. 2005 <http://proquest.umi.com/login>. This article from 1915 reports the angered reaction of famous evangelist Billy Holiday towards the Lusitania incident. With Christian leaders such as Sunday condemning German atrocities, it is easy to see why public opinion was quick to shift against Germany. "Disclaims German Crusade." New York Times 28 May 1917: 17. The New York Times. ProQuest Information and Learning. Lincoln High School Lib., Tallahassee, FL. 28 Mar. 2005 <http://proquest.umi.com/login>. This was George Sylvester Viereck and Victor F. Ridder's response to a report that the German-American Year Book would be propaganda for a "German collectivism" against the "peril of Anglo-Saxonism". Both of the German-Americans said they had no knowledge of a German movement against British influence; however, Viereck reaffirmed the rights of German-Americans to express their views as citizens of the United States. Viereck's response reinforces the fact that German-Americans should be allowed to form a peaceful partnership without suspicion. 17 "Edith Cavell, "Englishwoman, Put to Death on Charge of Aiding the Allies in Brussels." New York Times 16 Oct. 1915: sec. 1:4. This is an article that appeared in the New York Times three days after the execution of Edith Cavell. It gave a timeline of the events leading up to her execution. This news garnered much sympathy in the United States. Forster, A. Haire. "Anglo-American Alliance: Two Nations Drawn Together Against Despotism, as in 1823." Letter. New York Times 9 Aug. 1917: 6. The New York Times. ProQuest Information and Learning. Lincoln High School Lib., Tallahassee, FL. 28 Mar. 2005 <http://proquest.umi.com/login>. This 1917 letter to the editor relates the Allied cause, particularly the Anglo-American cause, as a fight against despotism. The author compares the union of the United States and Great Britain in 1917 to the cooperation of the two nations in 1823 when rallying against the powers of the Holy Alliance. Basically portrays the belief held that the British and Americans were good, while Germany, etc. were evil "despots". "German Enemy of the U.S. Hanged by Mob." St. Louis Globe-Democrat 5 Apr. 1918. 6 Mar. 2005 <http://web.mala.bc.ca/davies/h324war/prager.lynching.1918.htm>. This 1918 newspaper article tells the events surrounding the murder of German-born Robert Prager. The article mentioned that Prager had recently attended a socialist meeting and had made negative comments about President Wilson (although he had previously signed himself up as an "enemy alien" as many German-Americans had to do). "German Language Barred in Grades." Milwaukee Sentinel 12 Mar. 1918. Wisconsin History. Wisconsin Historical Society. 6 Dec. 2004 <http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/teachers/lessons/wwi/pdfs/expressionfullpackage.pdf> Found in a 1918 Wisconsin newspaper, this article recounts the discontinuation of teaching the German language to specific school children. As a result of growing antiGerman sentiment, the use of the German language in schools, churches, and the press was attacked. "Germans Gloried in Cavell Murder." New York Times 26 September 1917. sec. 9:2. This article describes cruelty of the German soldiers who sent Cavell to her death. It glorified Cavell as a martyr, while it trashed the reputation of Germany as a whole 18 "German War Society Loyal To America." New York Times 16 May 1915: 1. The New York Times. ProQuest Information and Learning. Lincoln High School Lib., Tallahassee, FL. 28 Mar. 2005 <http://proquest.umi.com/login>. In this 1915 report, the leader of the Deutscher Krieger Bund von Nord Amerika, made up of 20,000 of the United States' leading German citizens praises President Wilson's message to Germany following the Lusitania incident, and says that if the United States goes to war with Germany, the members of his organization will fight against the Fatherland. This is proof of German-American loyalty. The president of the organization also mentions that "Natives of the Allied countries in America have already gone too far in expressing their own partisan feelings." "Germany Wars Against the World." New York Times 1 Feb. 1917: 10. The New York Times. ProQuest Information and Learning. Lincoln High School Lib., Tallahassee, FL. 28 Mar. 2005 <http://proquest.umi.com/login>. This newspaper article from early in the war makes note of German the blockades' violation of neutral shipping rights. It specifically singles out Germany, "...this is a German act, it is Germany alone...", and calls the latest blockade "the proclamation of a new career of crime...." Because this article singles out Germany so specifically among the enemies, it is not hard to understand why other enemy nations such as AustriaHungary were not consistently a target of American opinion as Germany was. "Illinoisan Lynched for Disloyalty." Chicago Daily Tribune 5 Apr. 1918. 6 Mar. 2005 <http://web.mala.bc.ca/davies/h324war/prager.lynching. 1918.htm>. This is a 1918 newspaper article recounting the circumstances surrounding the lynching of German-American Robert Prager. It described the humiliation Prager suffered at the hands of a mob. "Jury Finds Prager Defendants Not Guilty and Others are Free." Edwardsville Intelligenser 18 Jun. 1918. 6 Mar. 2005 <http://web.mala.bc.ca/davies/h324war/prager.lynching.1918.htm>. This is an article from 1918 chronicling the trial of those responsible for Robert Prager' s murder. All on trial were acquitted. An example of how anti-German feeling had invaded rural America, even the Midwest, by 1918. 19 K., E. “The German Viewpoint: A Further Statement of the German-Americans’ Position.” Letter. New York Times 12 Aug. 1914: 8. The New York Times. ProQuest Information and Learning. Lincoln High School Lib., Tallahassee, FL. 16 May 2005 <http://proquest.umi.com/login>. This letter to the editor defends Germany, saying that Germany was not the primary cause for the beginning of war, that German-Americans still hold respect for their homeland, and that Germany did not rise to world power status through militarism, but rather through perseverance and good education. Not all Americans, especially German-Americans, were convinced that Germany and militarism were the main culprits behind the war. Littlefield, Walter. “Treitschke, Whose War Doctrines Dominate Germany.” New York Times 11 Oct. 1914: SM4. The New York Times. ProQuest Information and Learning. Lincoln High School Lib., Tallahassee, FL. 16 May 2005 <http://proquest.umi.com/login>. This article written a few months after the beginning of WWI attacks partisan German historian Heinrich von Treitschke. Littlefield implies that writings by nationalists such as Treitschke and Bernhardi were polluting Germany. Littlefield says “that nobody outside of Germany believed that any intelligent, modern community could sanely contemplate [Treitschke’s beliefs].” Rhetoric like Littlefield’s, although possibly based in truth led some to believe that all Germans were fervent nationalists ready to take over Europe. "Miss Cavell's Death Inflames England." New York Times 22 October 1915. sec. 2:3. This 1915 article tells of the anger that was felt throughout Britain when news of the execution arrived. The execution of Edith Cavell was widely publicized to emphasize German atrocities. New York Times 8 May 1915: 3. The New York Times. ProQuest Information and Learning. Lincoln High School Lib., Tallahassee, FL. 28 Mar. 2005 <http://proquest.umi.com/login>. This article from the day after the Lusitania sinking reveals that Germany had sent warnings to Americans considering sailing through the war zone surrounding Britain, and that many shippers had apprehended that such a tragedy would occur weeks in advance. This information proves that the American passengers of the Lusitania should not have been completely unaware of the dangers of the voyage, and so it is not as if the Germans attacked without any warning. 20 Russell, B. "The Economic Myth: That England Entered the War to Crush a Commercial Rival." Letter. New York Times 21 Aug. 1915: 6. The New York Times. ProQuest Information and Learning. Lincoln High School Lib., Tallahassee, FL. 28 Mar. 2005 <http://proquest.umi.com/login>. This letter to the editor from 1915 refutes a professor's belief that Britain entered into war with Germany to end their economic rivalries. Proof that many Americans were specifically drawn to the British cause, fully believing that Britain had done all it could to avoid a war, and that if Britain's purpose in war had been to crush an economic rival, it could have done so without such a worldwide ordeal. "St. Louis Germans Loyal." New York Times 15 May 1915: 5. The New York Times. ProQuest Information and Learning. Lincoln High School Lib., Tallahassee, FL. 28 Mar. 2005 <http://proquest.umi.com/login>. This 1915 article reports that the German-American leaders of St. Louis are completely behind President Wilson's cause, and the American cause. The president of the GermanAmerican Alliance states that although Britain's starving of the non-combatants in Germany is questionable; there are no such things as hyphenated Americans. "Washington Stirred by Execution Story." New York Times 23 October 1915. sec. 1:3. This provided evidence of the transplanting of anti-German feeling from Britain to Germany as a result of German "war crimes". The execution of Edith Cavell contributed greatly to a loss of respect for all things German, and contributed to the "Hun" myth. Primary Images Destroy This Mad Brute. Poster. 1915. 14 Feb. 2005 <http://bss.sfsu.edu/internment/postergor.html>. A propaganda poster and primary source from the middle of the war, it is an image of a German soldier carrying off an innocent woman. This is another piece of propaganda helpful in illustrating the attempts of the British-influenced CPI to unify the Americans against the Germans. 21 Lusitania: Europe via Liverpool. Advertisement. New York Times 1 May 1915: 19. The Americans. McDougal Littell. 31 Mar. 2005 <http://metatext.com/cpg.jrun?bookld=70269&pageld=1486173&mosaicld=0&demo=tru e>. The advertisement for the Cunard Lines' voyage dates includes a notice from the Imperial German Embassy that reminds passengers of the danger of traveling around the British Isles due to the German U-boats in the area. Warnings like this were produced to warn American liner passengers, and so the Lusitania passengers should not have been completely unaware of the danger inherent in their voyage. McAdoo, W. G. "Keep 'Em Going". Poster. 1917. Alderman Library, University of Virginia. American Passages. 14 Feb. 2005 <http://www.wadsworth.com/history_d/special_features/ext/ap/chapter22/22.2.prussian.h tml>. An image of an American train charging towards the Kaiser from 1917, this is another illustration of propaganda made to spread anti-German sentiment, using a favorite target hated as much as Hitler, Kaiser Wilhelm II. Raemaekers, Louis. Thrown to the Swine: The Martyred Nurse. Illustration. 1915. Spartacus Encyclopedia. 14 Feb. 2005 <http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/ARTraemaekers.htm>. A primary source illustration from 1915, it is a drawing by a Dutch artist that was appalled by German atrocities in Belgium. Portrayed the Germans as swine, it inferred the Edith Cavell incident. This poster provided a convincing argument against the Germans to the average Brit or American. Roberts, William. The First German Gas Attack at Ypres. Oil on canvas. 1918. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. Art of the First World War. 14 Feb. 2005 <http://www.art-wwl .com/gb/texte/019text.html>. A painting of Germans gassing Allied soldiers. Hints at the bitter feelings held toward Germans by Allied countries. A primary source, it was created during the time period, and is an artist's rendition of a specific event, espousing the emotions felt during the time. Spear, Fred. Lusitania woman and child drowning. Poster. N.d. "Riddle of the Lusitania.'" By Robert D. Ballard. National Geographic Apr. 1994: 75. This is a primary source poster that illustrated a woman and child drowning after the torpedoing of the Lusitania in 1915. This is an example of the atrocity propaganda that appealed to the emotions created by British propagandists. 22 Strothmann, F. Beat Back the Hun. Magazine cover page. 1918. The Rhino. Learn to Question.Com. 14 Feb. 2005 <http://www.learntoquestion.com/resources/db/cgi/jump.cgi?ID=548>. This poster portrays an example of the way German soldiers were viewed in the Allied countries in WWI: they were viewed as Huns. A primary source, it was the cover of a 1918 magazine. Take Up the Sword of Justice. Poster. 1914-1918. 14 Feb. 2005 <http://www.minerva.unito.it/Theatrum%20Chemicum/Pace&Guerra/UK/UK6.htm>. This WWI era poster is an example of British atrocity propaganda surrounding the Lusitania incident. With goddess Minerva in the foreground sounding a call to arms, and the sinking Lusitania with drowning victims in the background, this poster is the sort of atrocity propaganda created to encourage involvement in the war effort. Walker, A. B. "Babes on Bayonettes." Cartoon. Life 1915. 3 Dec. 2004 <http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/6648>. This is a political cartoon from Life. It portrays a German soldier, maybe the Kaiser even, bayoneting Belgian children. This serves as an example of the exaggeration of wartime incidences that caused Americans to turn toward the Allied cause and against Germany. A primary source, it is a cartoon from the time period. World War I Menace. N.d. Learn to Question.Com. 14 Feb. 2005 <http://www.learntoquestion.com/resources/db/File_Types/Posters_etc/>. This is a negative portrayal of a German encroaching on the White House, a symbol of American democracy. A primary source, it was an ad selling U.S. war bonds from the time period that conveyed the idea that buying war bonds could stop the "Huns" from trampling American ideals such as freedom, liberty, and democracy. Primary Miscellaneous Gerard, James W. "Loyalty." Rec. 25 Nov. 1917. Loyalty. Brooklyn Academy of Music. Center for History and New Media. 6 Dec. 2004 <http://chnm.gmu.edu/features/voices/wwlgerman/warongerman.html>. This primary source is a recording of an original speech about the consequences for German-Americans if they were disloyal to the American cause. It is an example of the swaying of American politicians into a pro-Ally anti-German stance that caused them to give speeches on the necessity of German-American loyalty. 23 Great Britain. Committee on Alleged German Outrages. The Bryce Report. By James Bryce.1915. First World War.Com. Ed. Michael Duffy. 2005. 14 Feb. 2005 <http://www.firstworldwar.com/source/brycereport.htm>. A British government document from 1915, it added legitimacy to eyewitness accounts of German atrocities in Belgium. It was used as an example of propaganda that made claims against Germany "legitimate", and that caused a pro-Ally shift in America. Krenke, R. Letter to Emanuel L. Philipp. 21 Oct. 1918. Emanuel L. Philipp Papers. Wisconsin Historical Society. Wisconsin History. Wisconsin Historical Society. 6 Dec. 2004 <http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/teachers/lessons/wwi/pdfs/expressionfullpackage.pdf> This is a 1918 letter from a German- American pastor to the governor of Wisconsin, refuting suggestions that his congregation is disloyal due to their holding of Germanlanguage services. The letter was used to verify the fact that many Americans were paranoid and wanted to Anglicize the "enemy" culture. A letter from the time period photocopied, it is a primary source Niebuhr, Reinhold. "The Failure of German-Americanism." Atlantic Monthly 1916: 13-18. History Matters. 2002. 14 Feb. 2005 <http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/4971>. A primary document, it is an article from the period, in which the author argues the case that the German- Americans were responsible for the accusations of disloyalty that had come down upon them for their support of the homeland. The article was helpful in identifying a reason for German-American discrimination: support for the "Fatherland". United States. Special Committee on Investigation of the Munitions Industry. The Nye Report. 24 Feb.1936. Resources for the Study of International Relations and Foreign Policy. Ed. Vincent Ferraro. 1 Jan. 2004. Mount Holyoke College. 16 May 2005 <http://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/nye.htm>. This is the Nye Report, released in 1936 by the Special Committee on Investigation of the Munitions Industry. It suggested that the primary reasons for America's entrance into WWI were American bankers loaning to the Allies and American munitions sales to the Allies. The economic ties between the United States and Allied nations created by bankers and munitions salesmen increased the need for an Allied win, and so eventually the United States would formally join the Allied effort. Wilson, Woodrow. War Messages, 65th Cong., 1st Sess., Senate Doc. No. 5, Serial No. 7624. Washington: 1917, 3-8. In Historic Documents of World War I, ed. Louis L. Snyder, 15255. Princeton: Van Nostrand, 1958. This is Woodrow Wilson's war message to Congress from April 2,1917. This message is an example of the Anglophile tendencies held by many upper class Americans that led to American involvement in the war. 24 Secondary Books Bailey, Thomas A., and Paul B. Ryan. The Lusitania Disaster. New York: The Free Press, 1975. This is a book that delves into the sinking of the Lusitania. It provided in depth background information on the event, and gave a general history, adding to general knowledge about the event. Bosco, Peter I. America at War: World War I. New York: Facts on File, 1991. This book proved to be an invaluable resource on the American war effort at home and abroad. It included information on the suppression of German culture in America, and the effect that British propaganda had on America. Childs, Harwood L. Dictionary of American History Volume V, S-Z. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1940, 1960. This encyclopedia of American History had a great section on the British propaganda machine's infiltration of America. It included brief but helpful information on Lord Northcliffe and Sir Gilbert. Connors, Michael F., Dr. Dealing in Hate: The Development of Anti-German Propaganda. Newport Beach: Institute for Historical Review, 1996. Institute for Historical Review. 2004. Institute for Historical Review. 6 Dec. 2004 <http://www.ihr.org/books/connors/dealinginhate.html>. An online book, it gave a great explanation for the development of anti-German feelings and propaganda in Britain and America, and was helpful in understanding the multiple issues (economic, militaristic, etc.) involved in the development of anti-German sentiment in Europe. Fleming, Thomas. The Illusion of Victory: America in World War I. New York: Basic Books, 2003. A book focusing on American and WWI, it provided an excellent history for the time period, and was used to compile the history behind German-American discrimination, the CPI, and the influence of British propaganda in America. It included detailed references to the background politics of the period and United States/Allied relations. Heyman, Neil M. Daily Life During World War I. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2002. This is another book that provided a few paragraphs on Germanophobia in America. It also described daily life on the home front and abroad. 25 Kunz, Virginia Brainard. The Germans in America. Minneapolis: Lerner Publications, 1966. This book provided a less-detailed history of the Germans in the United States. It provided much information on German-American contributions to American history and society. Lawson, Don. The United States in World War I. Toronto: Fitzhenry & Whiteside Limited, 1963 Another interesting resource on the United States in the First World War, it covered the home front experience well. Peterson, H.C., Propaganda for War: The Campaign Against American Neutrality. Port Washington, N.Y.: Kennikat, 1968 reprint of 1939 ed., 55. Quoted in Thomas Fleming, The Illusion of Victory: America in World War I, 52. New York: Basic Books, 2003. This quote from the Americans who were sent to investigate Belgian atrocities included in Propaganda for War shows the biased reporting and exaggeration of events used by the British to create a pro-Ally campaign. Ponsonby, Arthur. "The Manufacture of News in War-Time." Historic Documents of World War I. By Louis L. Snyder. Princeton: Van Nostrand, 1958. 137-138. A collection of primary sources compiled to show the manufacture of news as information passed from one Allied newspaper to another. Provided evidence for falseadvertising in wartime. Rippley, La Vern J. The German-Americans. Boston: G.K. Hall, 1976. This excellent book gave an in depth history of the Germans in America. It gave valuable background information for understanding the multiple and wide-reaching changes the German-American community experienced during WWI. Roosevelt, Theodore. Fear of God and Take Your Own Part New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1916, 279. Quoted in Nate Williams, "German-Americans in World War I." Western Front Association, <http://www.wfa-usa.org/new/germanamer.htm>. 7 Mar. 2005. A valuable quote from a famous American politician, it exposed the views held by many upper-class Americans about the "hyphenates". It showed the hostile feelings of many Americans towards the Germans in the country, and their wishes that these immigrant groups would assimilate. 26 Ross, Stewart Halsey. Propaganda for War: How the United States Was Conditioned to Fight the Great War of 1914-1918. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland and Co., 1996, 27-28. Quoted in Thomas Fleming, The Illusion of Victory: America in World War I, 45. New York: Basic Books, 2003. This quote from a German ally deftly exposed the biased reporting that reached the United States because of the British deliberate cutting of Germany's underwater communication cables. Snyder, Louis L. Historic Documents of World War I. Princeton: D. Van Nostrand, 1958. A secondary source that compiles numerous primary documents from World War I, it was extremely helpful in showing the ways news could be manufactured. It also included many interesting correspondences between political figures, and various speeches made by politicians such as Woodrow Wilson. Sowell, Thomas. "The Germans." Ethnic America. New York: Basic Books, 1981. 42-68. This book about immigrant groups to America included a section on German immigrants. It provided a useful brief history of the Germans in America from colonization times to World War II. Stokesbury, James L. A Short History of World War I. New York: William Morrow and Company, 1981. This was another useful resource that gave an overall history of World War I. It was helpful in discovering the reasons for each country's entry into the war, and the agendas behind many actions taken by the nations involved, primarily Britain. Tuchman, Barbara. The Zimmerman Telegram. New York: Ballantine Books, 1985,10-11. Quoted in Thomas Fleming, The Illusion of Victory: America in World War I, 4. New York: Basic Books, 2003. This quote from The Zimmerman Telegram illustrated the difficulties Germany had in expressing its point of view on the war to neutral countries such as the Untied States because of Britain's deliberate creation of communication barriers. Wilmott, H. P. World War I. New York: Dorling Kindersley, 2003. This was another good resource for a general overview of World War I. It was useful in researching German "atrocities". It described the fears contributing to anti-German paranoia, and how people acted on these fears. 27 Secondary Websites Adams, Willi Paul. The German Americans: An Ethnic Experience. 1990. Trans. La Verne J. Rippley and Eberhard Reichmann. Indianapolis: Max Kade German-American Center, 1993. German Information Center. 1993. Max Kade German-American Center. 14 Feb. 2005 <http://www.ulib.iupui.edu/kade/adams/cover.html>. This proved to be a useful history of the Germans in America from a reliable source on German America, the Max Kade center. It covered the assimilation of the GermanAmericans during WWI well. Duffy, Michael. First World War. Com. 2005. 14 Feb. 2005 <http://www.firstworldwar.com/>. A wonderful resource for the history of World War I, it includes many articles and primary resources relating to British, German, and American propaganda. It provided useful summaries of events and biographies of influential people from the time. "The War on German Americans." Listening to WWI: The War at Home. Center for History and New Media. 14 Feb. 2005 <http://chnm.gmu.edu/features/voices/wwlgerman/warongerman.html>. This proved to be an interesting site with multiple links to information on GermanAmerican discrimination during WWI. It provided personal accounts of anti-German discrimination. War Propaganda Bureau. 14 Feb. 2005 <http://http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/FWWwpb.htm>. This article explained the creation and history of the British war propaganda machine in depth. It also included helpful links related to the British propaganda efforts. Secondary Essays Ballard, Robert D. "Riddle of the Lusitania" National Geographic Apr. 1994: 68-85. This article about the undersea exploration of the Lusitania wreckage provides various hypotheses on how much damage the German submarine actually did to the ship, and provides information on the warnings sent to America about traveling through the dangerous waters surrounding Great Britain. 28 Delwiche, Aaron. "Of Fraud and Force Fast Woven: Domestic Propaganda During The First World War." First World War.Com. 13 Feb. 2005. A revealing essay, this resource provided in depth information on the founding of the CPI, atrocity propaganda, and British manipulation of American public and governmental opinion during the war. Epstein, Jonathon A. "German and English Propaganda in World War I." Unpublished essay, 2000. New York Military Affairs Symposium. 14 Feb. 2005 <http://libraryautomation.com/nymas/propagandapaper.html>. This essay provided a detailed description of German and British propaganda techniques and propagandists in World War I. It gave a helpful glance into the machinery running behind the scenes. Wells, Robert A. "Mobilizing Support for War: An Analysis of American Propaganda During World War I." 27 Mar. 2002. International Studies Association, New Orleans Archives. 14 Feb. 2005 <http://http://www.isanet.org/noarchive/robertwells.html>. This source provided a useful in depth history of American World War I propaganda, and the techniques utilized by the United States government to mobilize support for the war. The source was used in describing the period of American "neutrality" and the creation of the CPI. Williams, Nate. "German-Americans in World War I." Western Front Association. 7 Mar. 2005. <http://www.wfa-usa.org/new/germanamer.htm>. This essay gave an insightful look into the problems faced by German-America after Germanophobic sentiment began to filter in to the United States from Britain. Secondary Interviews Clyde, Lola Gamble. Interview. Nobody Would Eat Kraut. Rec. 1976. 3 Dec. 2004 <http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/2/>. This is a recorded interview with a woman that was alive during WWI. The interviewee describes the attacks on all things German in her childhood town. It was useful in understanding the real fear that was alive in America during WWI. Beard, Gary. E-mail interview. 17 Nov. 2004. This was an interview via e-mail about a man's German ancestors having to prove their loyalty. It provided evidence of the suppression of German-American culture. 29 Glaser, Gary. E-mail interview. 17 Nov. 2004. This was an interview by e-mail in which the interviewee describes an ancestor's individual encounter with wartime paranoia. The interview was used as an example of the suspicions that German-Americans dealt with. Ortel, Rebecca S. Personal interview. 3 Dec. 2004. A personal interview, it focused on the interviewee's German-American grandfather's experience with German discrimination as he was shipped over to fight for the Allies. The interview serves as evidence for the unreasonable suspicion Anglo-Americans felt towards German surnames. Ziemer, Eric. E-mail interview. 17 Nov. 2004. An interview via e-mail, it focused on the individual encounters with anti-Germanism faced by the interviewee's relatives alive during WWI, and served as evidence of antiGerman discrimination.