First Look at Hawthorne`s “Young Goodman Brown”: The Context of

advertisement

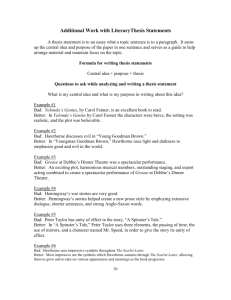

First Look at Hawthorne’s “Young Goodman Brown”: The Context of a Christian Community Nathaniel Hawthorne is writing much later than the early colonial writers. He was born in 1804 and died in 1864 and lived, among other places, in Concord, MA, in a neighborhood with other famous writers such as Emerson, Thoreau, and Louisa May Alcott. The neighborhood was home to a burgeoning movement known as Transcendentalism (more about that later). Hawthorne is the first characteristically American writer of fiction in our course. In much of his writing, the bliss of married life is addressed, and he is cherished for moral, delicate, old-fashioned and somewhat sentimental qualities in his writing. It is pleasant to read Hawthorne, and rather easy to “get into.” Even so, Ralph Waldo Emerson said of him that he “rode his dark horse of the night too exclusively.” How can his stories be so pleasant and comfortable, yet so dark? He writes using a simple style, with very obvious symbols, to address serious questions of faith and the soul. Hawthorne, writing many years after the Puritan era and its events such as the Salem Witchcraft Trial (see link), forces his readers to enter into the realm of a traditional Christian community, but scrutinizes its individuals and looks back at the Puritan era with a critical eye. Hawthorne does not reject Christianity outright in his stories and novels, but he is looking critically at the behavior of Christians. As you read “Young Goodman Brown”, consider the following questions: Where is Young Goodman Brown going? (what meeting, where located) Whom/What does he meet on the way there? Who is his guide? Whom does the guide resemble? What does the guide’s staff resemble? Who is the guide really? When the guide says, “I helped your grandfather, the constable, when he lashed the Quaker woman so smartly through the streets of Salem. And it was I that brought your father a pitch-pine knot, kindled at my own hearth, to set fire to an Indian village, in King Phillip’s war” Hawthorne is echoing the fact that his ancestors took part in the excesses of Puritanism, such as the Salem Witchcraft Trials, a connection that Hawthorne found unappealing. What other people does Young Goodman Brown encounter on the way to, or at, the Devil’s Sabbath? Consider the symbolism found in the names. Young Goodman Brown’s name would indicate that he is a respectable Christian member of the community. The same is true of Goody Cloyse, his Sunday School teacher from childhood. Consider how she addresses the Devil! Is Hawthorne criticizing Christianity, Christians, or Young Goodman Brown? Why does Hawthorne have Brown say, when he arrives late for his meeting with the devil, “Faith kept me back awhile.” What are the two meanings of the one line? Also, as Brown and the devil proceed, Brown hesitates, saying, “Not another step will I budge on this errand. What if a wretched old woman do choose to go to the devil, when I thought she was going to Heaven! Is that any reason why I should quit my dear Faith, and go after her?” Again, Faith has more than one meaning here. It is not long before Brown hears the voice of his wife Faith in the heathen wilderness at the Devil's Sabbath. Her pink ribbon (note that it is pink and not pure white) floats down. Faith and Brown are shown to each other at the gathering and the Devil says, “Depending upon one another's hearts, ye had still hoped, that virtue were not all a dream. Now are ye undeceived! Evil is the nature of mankind. Evil must be your only happiness.” Do you think Hawthorne agrees with this judgement? What does this vision do to Brown when he returns home? Even if it had only been a dream, the vision alters him. How does he change? What is Hawthorne saying in the effect the vision has on Brown? Knowing the sinfulness of others, how does Brown now treat others? How does he treat Faith? What, perhaps, does Brown fail to understand, for example when he is in church (in the last paragraph of the story)? Does Brown end his life happily? When a character ends his life unhappily, we might infer that the author is showing us how NOT to live. It is important not to confuse what Brown thinks with what Hawthorne thinks. A Second Look at Young Goodman Brown: The Romantic Context Is Hawthorne's story realistic or romantic? Are some of the events and images fantastic? Hawthorne described two kinds of writing: He described the novel as maintaining “very minute fidelity not merely to the possible, but to the probable and ordinary course of man's experience.” How does our short story fit Hawthorne's description of the novel? Are the events of “Young Goodman Brown” ordinary and probable? Have you experienced them. Or, does his description of Romance fit better: he says of Romance that “as a work of art, it must rigidly subject itself to laws, and while it sins unpardonably, so far as it may swerve aside from the truth of the human heart, has fairly a right to present that truth under circumstances, to a great extent, of the writer's own choosing or creation. [Romances] mingle the Marvellous rather as a slight, delicate, and evanescent flavor, than as any portion of the actual substance of the dish offered to the public” (bold is mine). Do we not see in things like the spiritual names, the eerie snake-like staff of the Devil, and the question of whether the Devil's Sabbath is real or a dream, examples of the marvellous? What other examples can you find? How do you respond to the fantastic elements? Do they make you disbelieve the story? Do they draw you in? Do they make the spiritual points of the story more significant or real to you? After reflecting on these notes, please check out the Hawthorne prompt under Collaboration, and reflect on the Christian issues and the Romantic style within the story.