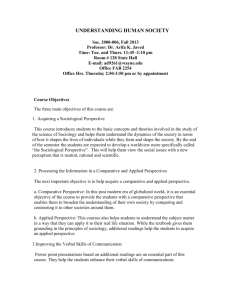

Course Objectives - Covenant College Sociology Department

advertisement

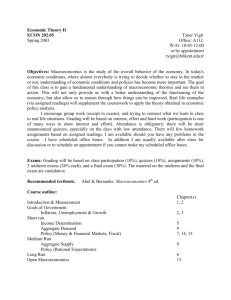

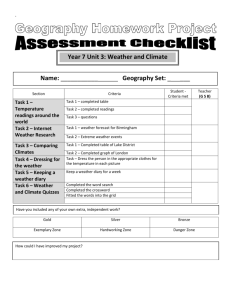

SOC 344 SYLLABUS: MEN, WOMEN, & SOCIETY Spring Semester 2015 Location:BH 120 MWF, 2:00-2:50 Matthew S. Vos – Instructor Work Phone: 419-1419 Cell Phone: 423-314-8790 e-mail: vos@covenant.edu Office: BH 107 Office Hours: TBA Required Texts: Ryle, R. (2012). Questioning Gender: A Sociological Exploration. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press. James, C. C. (2011). Half the Church: Recapturing God’s Global Vision for Women. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan. Each student must have the required texts to continue in the course. Introduction “So God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them” (Genesis 1:27). We cannot escape gender. When our parents first glimpse our barely discernible fetal bodies on the ultrasound screen, the main thing they want to know is whether we are male or female. And that bit of knowledge determines everything that follows. Once identified as one sex or the other, a social script is invoked – a script with narrow tolerances and which we will most likely follow quite carefully until the day we die. The early stages of our gendered scripts commonly involve pink or blue bedrooms stocked with cheerleader outfits or football helmets. And from there we imagine even the deepest parts of ourselves in gendered terms. Across the lifespan, to step outside of these very specific and mostly inflexible gender distinctions invariably means sanctions—some quite cruel. When it comes to gender, the pressures toward normalcy are, perhaps, more intense than for any other social category. But where does gender come from? Is the way we act out “male” and “female” natural, social, or some combination of both? And for Christians, how do we discern how God would have us act out these social categorizations? Do we accept masculinity as the world around us defines it? Are we content with the sexualized, domesticated images of women that pervade our consciousness? Are men and women, “the opposite sex,” or does sexual dimorphism SOC 344 prevent us from seeing that men and women are more alike than they are different? Furthermore, what are we to make of the profound inequality between men and women that is found virtually everywhere and at every stage of the lifecycle? This course is designed to help the student critically evaluate the “Men are from Mars; Women are from Venus” way of thinking about gender that pervades popular thought. The emphasis will be on understanding gender as a socially constructed and reified category. In this effort we will examine gender as a system of inequality, and consider what the scriptures tell us about men, women, and living together in a society that unilaterally distorts from God’s good intention for our lives in gendered bodies. Course Objectives 1. To define and distinguish between sex and gender and to help the student understand the various ways in which gender – the meaning of our identities and roles as men and women – is socially constructed. A major focus will be on challenging and deconstructing our generally simplistic way of understanding gendered behavior as “natural.” A. Instructional activities include: Lecture, Discussion, Videos, Readings. B. Primary means of assessment include: Exams, Research Paper, Gender Reflection Paper. 2. To identify and critically evaluate gender as a system of inequality. A. Instructional activities include: Lecture, Discussion, Videos, Readings, Panel Discussion. B. Primary means of assessment include: Exams, Research Paper. 3. To debunk the “Men are from Mars; Women are from Venus” myth, to understand the scientific flaws informing this perspective, and to understand how this way of understanding sexual identity can be harmful to both women and men. A. Instructional activities include: Lecture, Discussion, Readings, Panel Discussion. B. Primary means of assessment include: Exams, Research Paper, Quizzes, Gender Reflection Paper. 4. To examine how disciplines outside sociology study gender, with particular focus on how brain research has impacted our understanding of men and women. A. Instructional activities include: Lecture, Readings. B. Primary means of assessment include: Exams, Gender Reflection Paper. 5. To understand how we learn gender and to examine how gender influences our experiences in everyday life. A. Instructional activities include: Lecture, Discussion, Readings, Panel Discussion. B. Primary means of assessment include: Exams, Research Paper, Quizzes, Gender Reflection Paper. 6. To understand how gender impacts us institutionally in our families, work, religion, leisure, and politics. A. Instructional activities include: Lecture, Discussion, Readings, Panel Discussion, Videos. SOC 344 B. Primary means of assessment include: Exams, Research Paper, Quizzes, Gender Reflection Paper. 7. To explore various ways in which ideas about gender impact the church, with an emphasis on social justice. A. Instructional activities include: Lecture, Discussion, Readings. B. Primary means of assessment include: Exams, Quizzes, Gender Reflection Paper. Course Requirements/Assessments Midterm Examination: 15% (Objectives 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7) Final Examination: 20% (Objectives 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7) Genderography: 13% (Objectives 1, 2, 3, 5, 6) Research Paper (Social Issue Analysis or Content Analysis): 36% (1, 2, 5, 6) Readings Quizzes (Half the Church): 6% (3 x 2%) (5, 6, 7) Gender Reflection Paper: 10% (1,3,4, 5, 6, 7) There are several readings I have placed on electronic reserve. I will point them out to you as the class progresses. Attendance and Class Policy Much of the learning planned for you depends on your being here and cannot be gained simply by reading the course texts. Furthermore, your participation in class activities adds to the richness of the experience for other members of the class. You are permitted three absences (a full week of school) during this course. Beyond the allowed misses, every additional absence will result in a 3% reduction of your final grade for the course. In general, absences should be used for emergencies. For example, if a student missed three classes for personal reasons (leaving early for break, etc.) and then was sick for two classes later in the semester, those two absences would result in a 6% reduction in the student’s final grade (irrespective of their legitimacy). In other words, you are wise to plan on the unexpected coming up in the latter part of the semester, and not use up excused absences early on. Students are counted “present” if marked on the instructor’s attendance sheet and “absent” if they are not. It is the student’s responsibility to be present when the class roll is called. If you come in late and fail to alert me immediately after class, the omission will count as an absence. You may not be absent during test periods (unless you have a documented medical/family emergency). Any student found cheating on any portion of an SOC 344 assignment or test, fabricating any data for an assignment, or helping any other student cheat on any portion of the course will fail the course and may be withdrawn from the college. Please consult the 2014/15 Academic Bulletin before engaging in any cheating or plagiarism, so you can properly understand the penalties which may bear down on you. Technology use policy: To be decided as a class… Work that is late or exams that are missed due to a disciplinary action against a student may not be made up. I expect to be able to communicate with you using your college email address. For you to remain in this course, I require that you reply to any email I send you within a 24 hour period. Accordingly, you must check your college email every day. It also requires that you notify me if and when your email is down. Failing to reply to a communication that I initiate constitutes a lack of serious intent in the course, and may result in your being withdrawn. Students must submit assignments in hard copy. I do not print out and read e-mailed assignments except in extenuating circumstances such as a medical or family emergency. Assignments The instructor will provide ample notice before assignments (or exams) are due/given. The following may be used to record exam and assignment turn-in dates. Students should keep all graded assignments until after the course is completed. Assignment Due Date Grade Midterm Exam ________________ ______ Final Exam ________________ ______ Genderography ________________ ______ Paper ________________ ______ Readings Quizzes ________________ ______ Reflection Paper ________________ ______ As we work through the text and other course materials, I hope to use a variety of approaches to help you understand the concepts presented. However, although we may not specifically address all concepts presented in the text, please remember that you are still expected to read all of the material outlined in the following class schedule. SOC 344 Class Schedule Topic/Class Activities Reading Intro Introduction to the course Essentialism and Constructionism Syllabus/Student intros Chapter 1 Sociology & Gender Theoretical approaches to gender Feminist theories, Sociological theories, etc. Chapter 2 James Intro/Ch. 1 Video: Half the Sky Voices outside Sociology Psychology, Anthropology, Sociobiology, etc. Chapter 3 James Ch. 2 Video: It’s a Girl Eliot Chapter/Reserve Paris Chapter/Reserve Learning Gender Theories of Gender Socialization Learning Gender never ends Peer Groups, etc. Chapter 4 James Ch. 3 Lucal Chapter/Reserve Gender & Sexuality Masculinity and Femininity Chapter 5 Sexual Scripts James Ch. 4 Sex and Society: Hist of Het and Homo Sexuality Bordo Chapter/Reserve Youtube: Purity Balls Midterm Exam Date: ______________________ Friendship & Dating The Gender of Friendship and Dating Opposite-sex Adult Friendships Courting, Dating, and Hooking Up Gender & our Bodies A History of Bodies The Beauty Myth Body Image, Masculinity & Femininity Gender, Marr. & Fam. A History of Marriage Demographics of Marriage Gendered Division of Labor Gender & Work “A Man’s Job” Masculinity and Work The Wage Gap Gendered Organizations Media, & Pop Culture Gendered Images Sexuality in Media Masculinity and Video Games Chapter 6 James Ch. 5 Hiebert Chapter/Reserve Tannen 2011 Ch/Resererve Chapter 7 James Ch. 6 Video: Killing Us Softly 4: Advertising’s Image of Women Chapter 8 James Ch. 7 Coontz Reading/Reserve Video: Honor Diaries Chapter 9 James Ch. 8/Conclusion Smith Reading/ Reserve Tannen 2006/Reserve Chapter 10 Video: The Codes of Gender SOC 344 The Masculine World of Sports: Leisure & Gender Gender, Politics & Power Masculinity & Power Institutional Power (Gender & Politics, etc) Beyond the Gender Gap Chapter 11 FINAL EXAM schedule (Click link for exam schedule) Additional Readings Bordo, Susan. 2006. “Pills and Power Tools.” In The Production of Reality: Essays and Readings on Social Interaction 4th ed., edited by Jodie O’Brien. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press. (4 pages) Coontz, Stephanie. 2006. “How History and Sociology can Help Today’s Families.” Pp. 7-17 in The practical skeptic: Readings in sociology (3rd ed.), edited by Lisa J. McIntyre. Boston: McGraw-Hill Higher Education. Eliot, Lise. 2009. Pink brain, blue brain: how small differences grow into troublesome Gaps—and what we can do about it. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Fine, Cordelia. 2010. Delusions of gender: how our minds, society, and neurosexism create difference. New York: W. W. Norton. Hiebert, Dennis W. 1996. “Toward Adult Cross-Sex Friendship.” Journal of Psychology and Theology, 24, 4:271-283. (11 pages) Jordan-Young, Rebecca M. 2010. Brainstorm: The flaws in the science of sex differences. Cambridge, MA: Havard University Press. Lucal, Betsy. 2011. “What it Means to be Gendered Me: Life on the Boundaries of a Dichotomous Gender System.” In Gender Through the Prism of Difference, edited by Maxine Baca Zinn, Pierrette Hondagneu-Sotelo, and Michael A. Messner. Toronto: Oxford University Press. (11 pages) Paris, Jenell Williams. 2011. “What is Defined as Real.” In The End of Sexual Identity: Why Sex is Too Important to Define Who We Are. Downer’s Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press. (15 pages) Smith, Dorothy. 2004. “Women’s Experience as a Radical Critique of Sociology.” Pp. 372-380. In Readings in social theory: the classic tradition to post-modernism (4th ed.), edited by James Farganis. Boston: McGraw-Hill. Tannen, Deborah. 2011. “Asymmetries: Women and Men Talking at Cross-Purposes.” SOC 344 Pp. 503-517 in Language and Gender: A Reader, 2nd edition. Edited by Jennifer Coates and Pia Pichler. Malaysia: Wiley-Blackwell. (14 pages) Tannen, Deborah. 2006. “Marked: Women in the Workplace.” Pp. 131-137 in The practical skeptic: Readings in sociology (3rd ed.). edited by Lisa J. McIntyre. Boston: McGraw-Hill Higher Education.