Essay & Writing Conventions Note Sheet Directions: Use the

advertisement

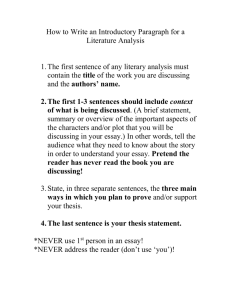

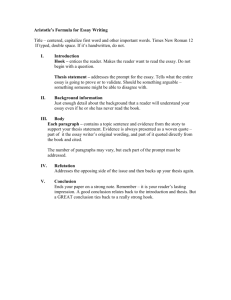

Essay & Writing Conventions Note Sheet Directions: Use the following list of conventions and explanations to guide your essay writing and revision process. Most of these rules apply to all formal writing; however, some are specific to Literary Analysis writing, so use them according to the style of essay that you are writing. Please note that intentional disregard of standard writing conventions will significantly affect your essay grade. You will be graded on everything that follows, so read this carefully. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. The English that we speak and the English that we write are two separate issues. Do not write the way you talk. Avoid slang and overused expressions/clichés unless they are in direct quotes, and use them sparingly in that case. Do not misspell words. On this note, be cautious of homophones and homonyms (too, to, two, their, they’re, there, etc.) as well. Spell check does not go beyond a fifth grade level, so you can’t expect it to catch words that are just used incorrectly or mixed-up. CAPITALIZE proper nouns, titles of books, and article titles. Avoid awkward (awk.) or unclear sentences. Usually, awkward and unclear sentences are created by incorrect punctuation and/or fragments and run-ons. Do not ask questions in your essay. Yes, this means no questions at all! Questions are usually cliché, repetitive, and unoriginal. Focus on making statements that make your reader think. Statements establish that you are the authority on the topic, where questions don’t create an authoritative or confident tone. Do not use contractions (don’t, can’t, won’t, etc.) unless they are in direct quotes. Contractions send the message that you are writing something informal, not a formal essay, and send the message to your reader that you are lazy. Do not end sentences with prepositions or with “it,” “is,” or “be.” You risk fragments by doing such because this type of phrasing will often create incomplete, unspecific, or unclear thoughts. Do not begin your Introduction with a direct quote or a question. Your Attention Grabber should be broad, universal, and your own words. Do not drop quotes into your essay without a transition and a lead-in. See the “Using Quotes in Essays” handout on my web site for examples of how to integrate quotes. Never use “a lot.” How much is “a lot”? Everyone’s answer will vary, thus you need to be more specific in your description. Avoid vague or weak words for description (good, bad, things, nice, really, big, small, etc.). Be more descriptive in order to establish tone and voice. Never use absolutes (always, never, everybody, everywhere, etc.). You might include or exclude someone or something that shouldn’t be included in your analysis. Never use first person pronouns when writing a literary analysis essay (I, me, my, mine, & myself) unless they appear in a direct quote. In lit analysis, the essay is not about you per say, it’s about you proving your thesis to be true through CDs and CM. The reader knows that you are the author, thus the reader also knows that your CM represents your opinion. There is no reason to use first person pronouns. Never use second person when writing a literary analysis essay (you, your, yourself, us, we, our, ourselves) unless they appear in a direct quote. Think about this: who are you including when you use second person? That’s right, you are including the reader, and the reader might not want to be included or the argument might not apply to the reader. Second person creates an assumption on the writer’s part. Assumption is very dangerous in a formal analysis essay because you can cause a reader to not want to read on, perhaps offend the reader, or actually end up arguing against yourself. Do not begin sentences with “This means that,” “This shows that,” “This displays that,” “The quote shows,” “I think,” “In my opinion,” “In this story,” or any variance of this type of phrasing. It’s unnecessary and sounds passive. Look and listen to the different tone that is created by word choice: a. NO: This means that Harry Potter did not deserve to be teased by the other kids. b. YES: Harry Potter did not deserve to be teased by the other kids. Sample “b” is more authoritative, direct, concise, and the meaning has not changed. Refer to fiction (most literature) in the present tense. It never really happened, so how can it be in the past? a. NO: Harry Potter was a misguided young man. b. YES: Harry Potter is a misguided young man. Refer to nonfiction in the past tense. Autobiographies and biographies are rooted in reality, thus they are believed to have happened. a. YES: America fought a war with England in the 18th Century. b. NO: America fights a war with England in the 18th Century. 18. In general, spell out numbers below 10 (double-digits). This rule often varies, but most grammar and writing convention guides suggest spelling out numbers under 10, but they also often approve of writing out any numbers that can be expressed in two or less words. 19. Never use sentence fragments in formal essay writing. Although fragments may often be used in creative writing, they are not employed in essay writing. 20. Avoid run-on sentences. Run-ons will lose the reader’s interest and often deter from your intended point. 21. Do not write in passive voice. Instead, opt for active voice whenever possible. Whenever possible, avoid the use of “To Be” verbs: am, is, are, was, were, has, have, & had. Active Voice: The subject performs the action. Rearrange the sentence so that the subject comes before the verb in order to create active voice. 22. If the essay is based on a book, short story, play, article, or poem, mention the author and title in the introduction, but not in the first sentence. The background or thesis is an appropriate place to mention the author and title. 23. Do not refer to the author by first name beyond the introduction, but do be sure to mention both the first and last name the first time the author is mentioned. After the introduction, just use the author’s last name. 24. Represent titles correctly: a. Book = underline the title or use italics (Of Mice and Men or Of Mice and Men) Generally speaking, use italics when typing, underline when writing by hand. b. Poem & Song Titles = quotation marks (“Richard Cory”) c. Short Story = quotation marks (“The Most Dangerous Game”) d. Play = underline the title or use italics (same as letter “a”) e. Magazine or Newspaper Title = underlined or italics (The New York Times, Seventeen) f. Article (newspaper, magazine, journal, etc.) = quotation marks (“Vancouver to be site of 2010 Olympics”) 25. Eliminate repetitive word choice. Avoid using key words more than twice per paragraph. Work on developing your vocabulary and use synonyms. Be careful of overusing the thesaurus. Your word choices must remain natural, not contrived, in order to create the appropriate tone and voice. 26. “Big words” do not necessarily make you sound smarter. Actually, they often create quite the opposite. “Big words” have the potential to make the reader focus on the words rather than the intended message. You also risk sounding unnatural in your word choice, thus negatively affecting your tone and voice. See #25 for more information. 27. Use appropriate transition words before concrete details (CDs). Know when to use which kind of transition. Refer to the transition handout on my web site for additional information. 28. Cited information in your essay must have the appropriate MLA citation in parentheses after the closing quotation marks, followed by a period. 29. Remember that introductions move from the general to the specific (your thesis) in about four to five sentences (attention grabber, background, thesis), and conclusions reverse that sequence, moving from specific (re-statement of thesis) to general in three to five sentences. 30. DO YOUR OWN WORK. Plagiarism (theft of someone’s ideas or intellectual property) is inexcusable. Cite your sources, use your own brain, and do not attempt to take credit for someone else’s work or ideas. Plagiarism will be dealt with according to the CVUSD and WHS policy.