OneL_Identity_Study_March_121.doc

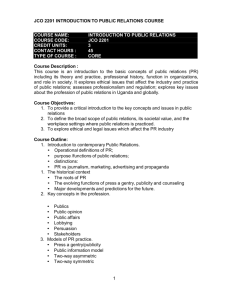

advertisement