Merchant of Venice booklet.doc

advertisement

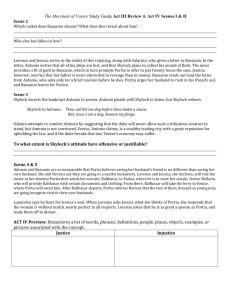

Essay Question “Which is the merchant here, and which the Jew?” 4.I.169 Portia’s question asks the audience to consider the many similarities between Antonio and Shylock, both merchants and money-lenders. Explore the ways in which Shakespeare portrays the two characters to show their differences and similarities. Remember to consider the following in your essay: the effects of characters and their actions the effects of dramatic devices and structures layers of meaning in language, ideas and themes the play’s social/ historical /cultural background and setting Give your own views in response to the ideas and themes Use quotations that allow you to explore ideas, characterisation and language in depth. General Criteria Shakespeare specific criteria Candidates give a personal and critical response to literary texts which show understanding of the ways in which meaning is conveyed. They refer to aspects of language, structure and themes to support their views. Candidates develop a perceptive Grade personal response. There is B understanding of the techniques by (37-42 which meaning is conveyed and of marks) ways in which readers may respond. They support their responses with detailed references to language, theme, structure and context. Candidates show insight when discussing: the nature of the play, its implications and relevance characters, structure and stagecraft Shakespeare’s use of language Candidates show analytical skill when exploring: the play’s implications, contemporary relevance and historical context characterisation, structure and theatricality Shakespeare’s use of linguistic devices Candidates appreciate and analyse Candidates show analytical and Grade alternative interpretations, making interpretative skills when evaluating: A cross references where appropriate. the play’s moral and philosophical (43-48 They develop their ideas and refer in context marks) detail to aspects of language, structure significant achievements within the and presentation, making apt and dramatic genre careful comparison within and Shakespeare’s exploitation of between texts. language for dramatic, poetic and figurative effect. Candidates make cogent and critical Candidates show originality of analysis Grade responses to texts in which they and interpretation when evaluating: A* explore and evaluate alternative and the play’s moral, philosophical or (49-54 original interpretations. They show social significance marks) flair and precision in developing ideas Shakespeare’s stagecraft and/or with reference to structure and appeal to audience presentation. Candidates make subtle patterns and details of words and and discriminating comparisons within images and between texts. Grade C (31-36 marks) 1 Going to the theatre in Shakespeare’s day. Theatre going was very popular in Elizabethan London, but it was very different from going to a play today. It was like a cross between going to a football match and going to the theatre. The playhouses were open air and the lack of artificial lighting meant that plays were performed in the daylight, normally in the afternoon. People paid a penny to get into the playhouse, so it was not cheap, since a penny was about one twelfth of a day’s wages for a skilled workman. Your penny let you into the large open yard surrounding the stage. The audience here had to stand, looking up at the actors, they were called the Groundlings. If people wanted a seat, then they had to pay another penny or twopence. This gave admission to the tiers of seating surrounding the yard, and also meant that you had a roof over your head. People with even more money could pay to have a seat in an enclosed room. So people of all incomes and social classes attended the theatre and paid for the kind of accommodation they wanted. While the audience was waiting for the play to begin, people had time to meet friends, talk, eat, drink – in fact they used to continue to enjoy themselves in this way while the play was being performed. But Elizabethan audiences were knowledgeable and enthusiastic. Watching a play was an exciting experience; although the stage was very big, the theatre was quite small, so no one was far from the actors. When an actor had a soliloquy he could come right into the middle of the audience and speak his thoughts in a natural, personal way. At the other extreme, the larger stage and the three different levels meant that whole battles could be enacted, complete with cannon fire, thunder and lightning and loud military music. There was no painted scenery, so that the audience had to use their imagination to picture the location of each scene, but Shakespeare always gave plenty of word clues in the characters’ speeches of when and where a scene took place. The lack of scenery to move about also meant that scene could follow scene without any break. On the other hand, the theatre companies spared no expense on costumes and furniture and other properties; plays also had live music performed by players placed either in the auditorium close to the stage, or in the gallery above it, if that was not to be used in the play. Although Londoners especially must have considered that going to the theatre was an exciting and important part of their lives; it is believed that up to a fifth of them went to the theatre regularly. Shakespeare and the company in which he became a share holder, The Lord Chamberlain’s Men, worked hard to become wealthy men. 2 Date of the Play Scholars have suggested that Shakespeare wrote The Merchant of Venice sometime between the late summer of 1596 and 1598. After several setbacks in the war against Spain, the Earl of Essex planned a naval expedition to attack and capture the Spanish port of Cadiz. Ninety-three English and 18 Dutch ships sailed from Plymouth in June 1596. Three weeks later they made a surprise attack on Cadiz, which was undefended. The Spaniards were burning their own ships to prevent their capture, but the English seized the San Matias and San Andres and took them back to England. The San Andres, a splendid ship, was renamed the Andrew. This dating is based on line 27 in Act 1 Scene 1: ‘And see my wealthy Andrew docked in sand.’ The likelihood is that The Merchant of Venice went into the repertory of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men in the 1597 season. The first performance of the play is not likely to have been given later than 1598 because that is the date given for its appearance in a register of published plays. Plays were not usually printed until after their first successful season on the stage. Jews in Shakespeare’s England Early History of Jews in England 1066 - The first Jewish communities came from Northern France, encouraged by William the Conqueror. Jews took up jobs trading and lending money, as Christians could not lend money for interest. Subsequent kings depended on loans from Jewish money lenders to finance wars. Unfortunately this resulted in Jewish communities being caught up in political in-fighting. In York in 1190 hundreds of Jews were besieged in the castle, many committed suicide and those who did not were murdered, the mob responsible was led by a nobleman who was in debt to the Jewish money lenders. 1231- The Earl of Leicester barred Jews from taking up residence in the city and forced landlords to pledge to keep them out. (It was not until January 2001 that the Leicester City Council formally renounced the nearly 800-year-old ban on Jews.) Expulsion 1290 - The Jews were expelled from England by Edward 1; it was the first European country to expel its Jewish residents. A few stayed and hid their identity, some converting to Christianity; many settled in France and Germany. Jews would not be allowed to live in England for another 350 years. The Jew of Malta 1589 – The Jew of Malta by Christopher Marlowe was first performed. The protagonist, Barabas, is an exaggerated villain, cunning and murderous. He refuses to pay the Crown and his wealth is seized. In revenge he poisons an entire nunnery and is finally put to death in a cauldron of boiling water. The play is clearly anti-Jewish, but it is also critical of Christian hypocrisy at a time when English Protestants were deeply suspicious of all other faiths including Catholics, Muslims and Jews. 3 Execution of Rodrigo Lopez 1594 – Rodrigo Lopez was physician to Queen Elizabeth 1. He was accused of plotting to poison her and was horribly tortured and executed. He was a Marrano –descended from Portuguese or Spanish Jews who were forced to be baptised as Christians, but who retained their Jewish identity and worshipped in secret. Contemporary accounts emphasise his foreignness, particularly his Jewish identity. The Rise of Italian City States By the end of the 16th century, Italy had developed the leading financial system in Europe. Shakespeare would have been aware of this and also that Venice had a thriving Jewish population, which was allowed to charge interest on loans, loans which in turn enabled trade to grow. Venetian Jews were, however, forced to live separately on their own island, the first Jewish ghetto, the Gheto Vechio. Badging The history of labelling those who are outside of mainstream society, literally by the enforced wearing of a badge, goes back many centuries and exists in several different cultures. The first recorded instance of badging religious or ethnic minorities occurs in Arabia in the reign of ‘Umar, the 2nd Caliph of the Islamic Empire in the mid-7th century A.D. Caliph ‘Umar introduced a law requiring all non-Muslims within the Islamic Empire (mainly Christians and Jews) to wear distinctive clothing, to make it easier for his tax collectors to identify those who were required to pay more tax. The Roman Church adopted this practice, applying it specifically to Jews throughout Europe. The practice spread to all the countries. There is evidence of this practice in England as early as the 12th century and the same for France, Italy and Germany. In Venice, the Senate decided to expel Jews from the city in 1394 due to complaints about unfair competition in the financial sector. Jews were allowed to work in the city for limited periods and were forced to wear various markings on their clothing to identify themselves. In 1394 they had to wear a yellow badge; it was changed to a yellow hat in 1496 and to a red hat in 1500. 4 Plot Overview Bassanio is desperately in need of money to court Portia, a wealthy heiress who lives in the city of Belmont. Bassanio asks Antonio, a Venetian merchant, for a loan in order to impress Portia. Antonio agrees, but is unable to make the loan himself because his own money is invested in trade ships that are still at sea, but will get a loan from one of the city’s moneylenders. In Belmont, Portia is at the mercy of her father’s will, which stipulates that she must marry the man who correctly chooses one of three caskets. None of Portia’s current suitors are to her liking, and she and her lady-in-waiting, Nerissa, fondly remember a visit paid some time before by Bassanio. In Venice, Antonio and Bassanio approach Shylock, a Jewish moneylender, for a loan. Shylock nurses a long-standing grudge against Antonio as he has made a habit of berating Shylock and other Jews for their usury, loaning money at exorbitant rates of interest, and by undermining their business by offering interest-free loans. However, Shylock offers to lend Bassanio three thousand ducats with no interest. Shylock adds, however, that should the loan go unpaid, he will be entitled to a pound of Antonio’s flesh. Despite Bassanio’s warnings, Antonio agrees. In Shylock’s household, his servant Launcelot decides to work for Bassanio and Shylock’s daughter Jessica schemes to elope with Antonio’s friend Lorenzo. That night, the streets of Venice fill up with revellers, and Jessica escapes with Lorenzo by dressing as his page. After a night of celebration, Bassanio and his friend Gratiano leave for Belmont, where Bassanio intends to win Portia’s hand. Bassanio arrives at Portia’s estate, and they declare their love for one another. Despite Portia’s request that he wait before choosing, Bassanio immediately picks the correct casket, and Gratiano confesses that he has fallen in love with Nerissa. The couples decide on a double wedding. Portia gives Bassanio a ring as a token of love, and makes him swear that under no circumstances will he part with it. The celebration is cut short by the news that Antonio has indeed lost his ships, and that he has forfeited his bond to Shylock. Bassanio and Gratiano immediately travel to Venice to try and save Antonio’s life. Shylock ignores the many pleas to spare Antonio’s life, and a trial is called to decide the matter. The duke of Venice announces that he has sent for a legal expert, who turns out to be Portia disguised as a young man of law. Portia asks Shylock to show mercy, but he insists the pound of flesh is rightfully his. Bassanio offers Shylock twice the money due him, but Shylock insists on collecting the bond. Portia examines the contract and declares that Shylock is entitled to the merchant’s flesh. Shylock ecstatically praises her wisdom, but as he is on the verge of collecting his due, Portia reminds him that he must do so without causing Antonio to bleed, as the contract does not entitle him to any blood. Portia informs Shylock that he is guilty of conspiring against the life of a Venetian citizen, which means he must turn over half of his property to the state and the other half to Antonio. The duke spares Shylock’s life and takes a fine instead of Shylock’s property. Antonio also forgoes his half of Shylock’s wealth on two conditions: first, Shylock must convert to Christianity, and second, he must will the entirety of his estate to Lorenzo and Jessica upon his death. Shylock agrees. Bassanio showers the young law clerk with thanks, and is eventually pressured into giving Portia the ring with which he promised never to part. The two women return to Belmont. When Bassanio and Gratiano arrive the next day, their wives accuse them of faithlessly giving their rings to other women. Before the deception goes too far, however, Portia reveals that she was, in fact, the law clerk, and both she and Nerissa reconcile with their husbands. Lorenzo and Jessica are pleased to learn of their inheritance from Shylock, and the joyful news arrives that Antonio’s ships have in fact made it back safely. The group celebrates its good fortune. 5 Dramatis Personae The Duke Of Venice The Prince Of Morocco, The Prince Of Arragon suitors to Portia. Antonio a merchant of Venice. Bassanio his friend, suitor likewise to Portia. Salanio, Salarino, Gratiano, Salerio friends to Antonio and Bassanio. Lorenzo in love with Jessica. Shylock a rich Jew. Tubal a Jew, his friend. Launcelot Gobbo the clown, servant to Shylock. Old Gobbo father to Launcelot. Leonardo servant to Bassanio. Balthasar, Stephano servants to Portia. Portia a rich heiress. Nerissa her waiting-maid. Jessica daughter to Shylock. Magnificoes of Venice, Officers of the Court of Justice, Gaoler, Servants to Portia, and other Attendants. 6 Shylock: Portrayals through the centuries “if you prick us do we not bleed…” 16th Century Richard Burbage and Will Kempe were two contemporaries of Shakespeare who played Shylock, supposedly with a red beard and a false nose. Burbage and Kempe’s portrayals were probably quite exaggerated: Shylock the monster, rather than a real person. 18th Century Charles Macklin played Shylock in a way which emphasised his greed and malevolence. It seems that audiences were surprised how realistic his portrayal was, evil but human. Macklin himself was a shady character, who had killed another actor in a fight over a beard. 19th Century Edmund Kean, in 1814, played Shylock with a black wig and beard and more contemporary costume. He attempted to show the human side of Shylock’s character, whose revenge is born out of his sense of persecution. The acting style of the time, however, worked against a subtle portrayal; he still shouted and ranted his way through the part. William Macready, in 1840, chose a more measured style of speaking and an aristocratic costume but it was Henry Irvine, in 1880, who portrayed an educated and noble Shylock, probably the most sympathetic so far, signifying the persecution of fellow Jews. 7 Irving’s first portrayal of Shylock coincided with the mass migration of Jews fleeing persecution from Russia and Eastern Europe. By the time of his final appearance as Shylock, in 1905, Britain had passed the Aliens Act, restricting the entry of Jews to the country, and Irving had reverted to a more caricatured portrayal of his greatest role. 20th Century After the Holocaust, contemporary knowledge gives a different emphasis to Shylock’s plight. In 1999, in Trevor Nunn’s production at the National Theatre, costumes echoed Germany in the 1930s and Henry Goodman’s Shylock was a psychologically complex, tragic hero, whose single flaw is his wish to be revenged upon Antonio. Miller [stage director] and Sichels’ [film director] 1973 production had Laurence Olivier playing Shylock (his farewell to stage Shakespeare). Some thought his Shylock was somewhat broad for the small screen; it provided a tantalising glimpse of how it might have come across in the theatre. Apparently at Miller's insistence, Olivier plays down the character's overtly Jewish characteristics, even to the point of having Shylock conceal his skull cap under a top hat whenever he goes about his public business. Miller has updated the action to the late 19th century, a time when Jewish bankers were hugely influential in central Europe, but before the overt anti-semitism of the Nazi era: here, it's much subtler but just as destructive. While most productions contrast Antonio (good) and Shylock (bad), here, they are almost indistinguishable in dress, speech and behaviour: it's only Shylock's ethnic origin that sets him apart from the rest of society. Tellingly, Miller cuts the line "I hate him for he is a Christian", underlining his view of Shylock as misunderstood victim. Olivier's animal howl of despair as the trial ends is so unnerving that even his harshest critics are visibly shaken. Shylock Although critics tend to agree that Shylock is The Merchant of Venice’s most noteworthy figure, no consensus has been reached on whether to read him as a bloodthirsty bogeyman, a clownish Jewish stereotype, or a tragic figure whose sense of decency has been fractured by the persecution he endures. Certainly, Shylock is the play’s antagonist, and he is menacing enough to seriously imperil the -happiness of Venice’s businessmen and young lovers alike. Shylock is also, however, a creation of circumstance; even in his singleminded pursuit of a pound of flesh, his frequent mentions of the cruelty he has endured at Christian hands make it hard for us to label him a natural born monster. On the other hand, Shylock’s coldly calculated attempt to revenge the wrongs done to him by murdering his persecutor, Antonio, prevents us from viewing him in a primarily positive light. Shakespeare gives us unmistakably human moments, but he often steers us against Shylock as well, painting him as a miserly, cruel, and prosaic figure. Antonio Although the play’s title refers to him, Antonio is a rather lacklustre character. He emerges in Act I, scene i as a hopeless depressive, someone who cannot name the source of his melancholy and who, throughout the course of the play, develops his self-pity even further, unable to muster the energy required to defend himself against execution. Antonio never names the cause of his melancholy, but the evidence seems to point to his being in love, despite his denial of this idea in Act I, scene i. The most likely object of his 8 affection is Bassanio, who takes full advantage of the merchant’s boundless feelings for him. Antonio has risked the entirety of his fortune on overseas trading ventures, yet he agrees to guarantee the potentially lethal loan Bassanio secures from Shylock. In the context of his unrequited and presumably unconsummated relationship with Bassanio, Antonio’s willingness to offer up a pound of his own flesh seems particularly important, signifying a union that grotesquely alludes to the rites of marriage, where two partners become “one flesh.” Further evidence of the nature of Antonio’s feelings for Bassanio appears later in the play, when Antonio’s proclamations resonate with the hyperbole and self-satisfaction of a doomed lover’s declaration: “Pray God Bassanio come / To see me pay his debt, and then I care not” (3.iii.35–36). Antonio ends the play as happily as he can, restored to wealth even if not delivered into love. Without a mate, he is indeed the “tainted wether" and he will likely return to his favourite pastime of moping about the streets of Venice (4.i.113). After all, he has effectively disabled himself from pursuing his other hobby—abusing Shylock—by insisting that the Jew convert to Christianity. Although a sixteenth-century audience might have seen this demand as merciful, as Shylock is saving himself from eternal damnation by converting, we are less likely to be convinced. Not only does Antonio’s reputation as an anti-Semite precede him, but the only instance in the play when he breaks out of his doldrums is his “storm” against Shylock (I.iii.132). In this context, Antonio proves that the dominant threads of his character are melancholy and cruelty. Antonio, Bassanio and homosexuality Antonio's unexplained depression—"In sooth I know not why I am so sad"—and utter devotion to Bassanio has led some critics to theorise that he is suffering from unrequited love for Bassanio and is depressed because Bassanio is coming to an age where he will marry a woman. In his plays and poetry Shakespeare often depicted strong male, which has led some critics to infer that Bassanio returns Antonio's affections despite his obligation to marry: ANTONIO: Commend me to your honorable wife: Tell her the process of Antonio's end, Say how I lov'd you, speak me fair in death; And, when the tale is told, bid her be judge Whether Bassanio had not once a love. BASSANIO: But life itself, my wife, and all the world Are not with me esteemed above thy life; I would lose all, ay, sacrifice them all Here to this devil, to deliver you. (4,i) Other interpreters of the play regard the conception of Antonio's sexual desire for Bassanio as questionable. Michael Radford, director of the 2004 film version starring Al Pacino, explained that although the film contains a scene where Antonio and Bassanio actually kiss, the friendship between the two is platonic, in line with the prevailing view of male friendship at the time. Jeremy Irons, in an interview, concurs with the director's view and states that he did not "play Antonio as gay". Other Characters PORTIA A wealthy heiress from Belmont. Portia's beauty is matched only by her intelligence. Bound by a clause in her father's will that forces her to marry whichever suitor chooses correctly among three caskets, Portia nonetheless longs to marry her true love, Bassanio. 9 Far and away the cleverest of the play's characters, Portia disguises herself as a young male law clerk in an attempt to save Antonio from Shylock's knife. BASSANIO A gentleman of Venice and a kinsman and dear friend to Antonio. Bassanio's love for the wealthy Portia leads him to borrow money from Shylock with Antonio as his guarantor. An ineffectual businessman, Bassanio nonetheless proves himself a worthy suitor, correctly identifying the casket that contains Portia's portrait. GRATIANO A friend of Bassanio's who accompanies him to Belmont. A coarse and garrulous young man, Gratiano is Shylock's most vocal and insulting critic during the trial. While Bassanio courts Portia, Gratiano falls in love with and eventually weds Portia's lady-in-waiting, Nerissa. JESSICA Although she is Shylock's daughter, Jessica hates life in her father's house and elopes with the young Christian gentleman Lorenzo. Launcelot jokingly calls into question what will happen to her soul, wondering if her marriage to a Christian can overcome the fact that she was born a Jew. We may wonder if her sale of a ring given to her father by her mother isn't excessively callous. LORENZO A friend of Bassanio and Antonio. Lorenzo is in love with Shylock's daughter, Jessica. He schemes to help Jessica escape from her father's house and eventually elopes with her to Belmont. NERISSA Portia's lady-in-waiting and confidante. Nerissa marries Gratiano and escorts Portia on Portia's trip to Venice by disguising herself as Portia's law clerk. LAUNCELOT GOBBO Bassanio's servant. A comical, clownish figure who is especially adept at making puns, Launcelot leaves Shylock's service in order to work for Bassanio. Relationships As well as the fraught relationship between Antonio and Shylock, there are a number of crucial character combinations in the play that need to be interpreted by the actors and the director. The following is a far from exhaustive list of connections to study and map. ANTONIO AND BASSANIO Are they more than friends? Does it matter? Male friendship in Shakespeare's day was likely to have been a lot more accepting of degrees of affection, even love, than in our society today. That said, what is your reaction to the opening scene in Antonio's bedroom in which Bassanio tells Antonio of his plans and asks for money. To what extent is this seduction? Or do you feel Antonio knows perfectly well what is going on? JESSICA AND SHYLOCK What is your view of this relationship? Shakespeare does not give the two characters much time together and then Shylock is always ordering the poor girl around. The truth of their relationship only really emerges once they are apart and reflect on their separation. What are these reactions? Do you feel there is much grief at parting? 10 Themes Conversion Is a theme running through the text; and ultimately seal’s Shylock’s fate. Religious & Cultural In Shakespeare’s time, to be converted to Christianity meant one’s soul was saved from hell. Elizabethan audiences would have welcomed Shylock and Jessica’s salvation as a happy ending. However, the history of forced conversions of the 16th century Inquisition in India and Europe, especially Spain and Portugal, and, in the 20th Century, the attempts of the Final Solution in Nazi occupied Europe to obliterate Judaism, leave modern audiences uneasy about such a sense of salvation. European imperialism in the 19th and 20th centuries engendered in African and Asian societies another sense of conversion - “Westernisation”. Many such societies felt their own values and customs under threat from the new ideas and technologies introduced by Western colonial powers. In the modern period, periodic resistance to “Americanisation” echoes the earlier struggles against forced religious conversion. Monetary The Merchant of Venice has the love of money at its core. Characters are keen to convert both commodities and opportunities for cash. Just as Jessica converts to Christianity for love of Lorenzo, he is able to convert marriage into an opportunity to become wealthy. She hides the ducats in her clothes, in a gesture resonant of centuries of refugees who have sewed their money into their clothes to keep it hidden and fund their flight. Bassanio has several creditors and marrying a rich woman will clear his debts, love and life itself can be exchanged for cash. Portia, bound by the conditions of her legacy, is able to convert the guessing game into an opportunity to marry the man she loves and we are reminded that “all that glisters is not gold.” Her inherited wealth gives her the confidence to speak with the accents of enlightened privilege but she must still convert her gender to take on the role of lawyer. Self-Interest Versus Love On the surface, the main difference between the Christian characters and Shylock appears to be that the Christian characters value human relationships over business ones, whereas Shylock is only interested in money. The Christian characters certainly view the matter this way. Merchants like Antonio lend money free of interest and put themselves at risk for those they love, whereas Shylock agonises over the loss of his money and is reported to run through the streets crying, “O, my ducats! O, my daughter!” (2.viii.15). With these words, he apparently values his money at least as much as his daughter, suggesting that his greed outweighs his love. However, upon closer inspection, this supposed difference between Christian and Jew breaks down. When we see Shylock in Act 3, scene i, he seems more hurt by the fact that his daughter sold a ring that was given to him by his dead wife before they were married than he is by the loss of the ring’s monetary value. Some human relationships do indeed matter to Shylock more than money. Moreover, his insistence that he have a pound of flesh rather than any amount of money shows that his resentment is much stronger than his greed. 11 Just as Shylock’s character seems hard to pin down, the Christian characters also present an inconsistent picture. Though Portia and Bassanio come to love one another, Bassanio seeks her hand in the first place because he is monstrously in debt and needs her money. Bassanio even asks Antonio to look at the money he lends Bassanio as an investment, though Antonio insists that he lends him the money solely out of love. In other words, Bassanio is anxious to view his relationship with Antonio as a matter of business rather than of love. Finally, Shylock eloquently argues that Jews are human beings just as Christians are, but Christians such as Antonio hate Jews simply because they are Jews. Thus, while the Christian characters may talk more about mercy, love, and charity, they are not always consistent in how they display these qualities. The Divine Quality of Mercy The conflict between Shylock and the Christian characters comes to a head over the issue of mercy. The other characters acknowledge that the law is on Shylock’s side, but they all expect him to show mercy, which he refuses to do. When, during the trial, Shylock asks Portia what could possibly compel him to be merciful, Portia’s long reply, beginning with the words, “The quality of mercy is not strained,” clarifies what is at stake in the argument (4.i.179). Human beings should be merciful because God is merciful: mercy is an attribute of God himself and therefore greater than power, majesty, or law. Portia’s understanding of mercy is based on the way Elizabethan Christians understood the difference between the Old and New Testaments. The Old Testament depicts God as requiring strict adherence to rules and exacting harsh punishments for those who stray. The New Testament, in contrast, emphasises adherence to the spirit rather than the letter of the law, portraying a God who forgives rather than punishes and offers salvation to those followers who forgive others. Thus, when Portia warns Shylock against pursuing the law without regard for mercy, she is promoting what Elizabethan Christians would have seen as a pro-Christian, anti-Jewish agenda. The strictures of Renaissance drama demanded that Shylock be a villain, and, as such, patently unable to show even a drop of compassion for his enemy. A sixteenth-century audience would not expect Shylock to exercise mercy—therefore, it is up to the Christians to do so. Once she has turned Shylock’s greatest weapon—the law—against him, Portia has the opportunity to give the mercy for which she so beautifully advocates. Instead, she backs Shylock into a corner, where she strips him of his bond, his estate, and his dignity, forcing him to kneel and beg for mercy. Given that Antonio decides not to seize Shylock’s goods as punishment for conspiring against him, we might consider Antonio to be merciful. But we may also question whether it is merciful to return to Shylock half of his goods, only to take away his religion and his profession. Antonio’s compassion, then, seems to stem as much from self-interest as from concern for his fellow man. Mercy, as delivered in The Merchant of Venice, never manages to be as sweet, selfless, or full of grace as Portia presents it. Hatred as a Cyclical Phenomenon Christians and Jews hate each other at all levels of society. Even Launcelot says "I am a Jew if I serve the Jew any longer," as if being a Jew is the worst think he can think of. When Jessica escapes with Lorenzo, Gratiano pays her the complement of calling her "a gentile and no Jew" (even though she had not yet converted to Christianity). Throughout the play, Shylock claims that he is simply applying the lessons taught to him by his Christian neighbours; this claim becomes an integral part of both his character and his argument in court. In Shylock’s very first appearance, his entire plan seems to be born of the insults and injuries Antonio has inflicted upon him in the past. As the play continues, and Shylock unveils more of his reasoning, the same idea rears its head over and over—he is simply applying what years of abuse have taught him. Responding to Salerio’s query of 12 what good the pound of flesh will do him, Shylock responds, “The villainy you teach me I will execute, and it shall go hard but I will better the instruction” (3.i.60–61). Not all of Shylock’s actions can be blamed on poor teachings, and one could argue that Antonio understands his own culpability in his near execution. With the trial’s conclusion, Antonio demands that Shylock convert to Christianity, but inflicts no other punishment, despite the threats of fellow Christians like Gratiano. Antonio does not, as he has in the past, kick or spit on Shylock. Antonio, as well as the duke, effectively ends the conflict by starving it of the injustices it needs to continue. Settings VENICE Shakespeare, as far as we know, never travelled abroad and never visited Italy or Venice. To an average London playhouse audience member in the late 1590s Venice would be as exotic and strange as Belmont – a completely fictitious realm. Today, travel shows and holidays have rendered Venice more familiar, so it is Belmont that will need to function as the more exotic of the two locations. What comes to mind when you think of Venice? BELMONT Belmont - meaning 'beautiful mountain' - is Shakespeare's invention. It is meant to contrast strongly with the world of Venice. The following speech is spoken by Bassanio explaining to Antonio why he must travel to Belmont and try his luck and judgment in the test that may give him Portia's hand and wealth. Bassanio: In Belmont is a lady richly left; And she is fair, and, fairer than that word, Of wondrous virtues: sometimes from her eyes I did receive fair speechless messages: Her name is Portia, nothing undervalued To Cato's daughter, Brutus' Portia: Nor is the wide world ignorant of her worth, For the four winds blow in from every coast Renowned suitors, and her sunny locks Hang on her temples like a golden fleece; Which makes her seat of Belmont Colchos' strand, And many Jasons come in quest of her What idea does this speech give you of both Portia and Belmont? Which words are repeated? Read through the speech highlighting in each line the key word that, for you, carries, the most meaning. What patterns does your eventual list contain, if any? What mood does the list suggest? The Courtroom Scene Imagine that you were responsible for staging or filming this key scene. The success or failure of the play hangs on the impact of the events here and the performances the actors muster. 13 Your task is to study the scene and continue this list of questions: How do we see the Duke and the Magnificoes that are to oversee the enforcement of Shylock's bond? How will we know that they have ultimate authority in this room? Where will they be placed? Where is Antonio - how does he enter and how does that entrance suggest the pressures he is under? How does Shylock enter? What is his mood? How does he react to the appeal from the Duke for mercy? In what way should Shylock perform his first speech 'I have possessed your grace…’ The sympathetic reading Many modern readers and theatergoers have read the play as a plea for tolerance as Shylock is a sympathetic character. Shylock's 'trial' at the end of the play is a mockery of justice, with Portia acting as a judge when she has no real right to do so. Thus, Shakespeare is not calling into question Shylock's intentions, but the fact that the very people who berated Shylock for being dishonest have had to resort to trickery in order to win. Shakespeare puts one of his most eloquent speeches into the mouth of this "villain": Hath not a Jew eyes? Hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions; fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, heal'd by the same means, warm'd and cool'd by the same winter and summer as a Christian is? If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you tickle us, do we not laugh? If you poison us, do we not die? And if you wrong us, shall we not revenge? If we are like you in the rest, we will resemble you in that. If a Jew wrong a Christian, what is his humility? Revenge. If a Christian wrong a Jew, what should his sufferance be by Christian example? Why, revenge. The villainy you teach me, I will execute, and it shall go hard but I will better the instruction. Act 3, scene i Do you think that Shakespeare meant to criticise Shylock or the Christians in the play? Do you think that because of the possible anti-semitic views in the play that this play should not be performed and / or taught any more? Related Activities/Discussion Questions a. Write your own definition of the word censorship. - Then look up the dictionary definition. Are they similar or do they differ? b. Plan for a debate whether or not censorship of The Merchant of Venice is ever an appropriate response to concerns about the promotion of anti-Semitism or prejudice. 14 What Is Your Vision Of Shylock? The play may have a title suggesting it is about Antonio but it is Shylock who, despite only a handful of appearances, often remains the main focus of attention. There have been thousands of interpretations of the character over the centuries. Even the versions of him on film, though far less numerous, demonstrate considerable variation. An early French movie called Shylock (1913) turned the character into a particularly grim caricature redolent. So money-grabbing was actor Harry Baur in the role, that he performed Shylock bathing with his gold coins and almost finding it impossible to hand over the cash to Antonio following their agreement. Whereas, the 1973 film of Jonathan Miller's National Theatre production records Laurence Olivier as a Shylock placed at the heart of nineteenth century society - virtually indistinguishable in appearance and desperately seeking assimilation. In this same cause most of his virulent anti-Christian lines were removed. In between these two interpretations lie the horrors of the rise of Nazism in Europe and the Holocaust. All post-war performances of The Merchant of Venice are rightly touched by the knowledge that the play exists somewhere on a cultural spectrum that has Auschwitz at one end of it. Discussing Shylock But does that mean that the play should not be performed? Or should, as in the Miller/Olivier stage production and film, Shylock's line ‘I hate him for he is a Christian…’ be removed? What is your vision of Shylock? In the play, he does not appear until the third scene and is not mentioned before he appears, unless Antonio's lines to Bassanio carry overtones of the kind of bargain Shylock will extract and the kind of physical danger he (Antonio) will carry alongside his overextended finances: ‘Try what my credit can in Venice do:/ That shall be rack'd, even to the uttermost, / To furnish thee to Belmont…’ Work your way though Act I, Scene 3 discussing the possibilities for interpretation that are on offer to an actor playing Shylock or a director creating this scene. For example: How might it begin? Will the opening with Shylock weighing up Antonio's request for three thousand ducats be in marked contrast to the scene and mood that has just concluded and which introduced us to the magical world of Belmont and its charmed inhabitants - Portia and Nerissa? (Radford's film begins with a shocking close-up of meat being cut and weighed in a market.) How might Shylock's refusal to give an immediate answer to the request be presented – sinister? - cautious? playful? - full of resentment? - amusement? How might an actor catalogue Antonio's current commercial concerns - leading up to the 'Pi-rats' joke? Again - is he turning the screw on Bassanio, enjoying the young man's discomfort and suspense or is he sensibly considering the kind of security the loan needs, given the fact that Antonio's wealth is literally 'all at sea'? 15 What of that first 'aside' speech in which Shylock is revealed to harbour all sorts of resentments against Antonio, the principal one being that he has undermined Shylock's business by offering interest-free loans (money-lending was about the only profession that Jews could perform in Christian societies of that time once the guilds protecting and regulating other trades had closed their ranks against allowing them in as members.) How will Shylock remind Antonio of his previous horrible behaviour towards him spitting on him where he does his business each day on the Rialto Bridge and its canal-side? Is Shylock's offer of friendship sincere? Where does the idea of the pound of flesh come from? Does it spring from Shylock's mind unprompted - as if the notion has been festering there as some sort of fantasy for some while, or does it proceed from the precise circumstances or surroundings that the characters are in? The Outsider in Shakespeare: Questions for discussion. The Merchant of Venice is a complex dramatic narrative, written at a time when to be black or Jewish placed one outside of Protestant white society. Over the centuries, actors and directors have been able to interpret the plays according to their own contemporary cultural norms. Gradually, it becomes unacceptable to wear a red beard and false nose of Jewish stereotype and, much later, it is considered deeply offensive for white actors to ‘black up’ in minstrel style make-up to play Othello. The first non-white actor to play Othello was a Bengali actor in India in 1803, although it takes more than 150 years for it to become normal practice to cast a black actor. The question is still asked: was Shakespeare racist? He gives us action and situation, creates societies with cruel notions of justice, but he gives no opinion of what he thinks of Othello and Shylock. Each has speeches which instil sympathy in the audience and each challenges the majority society. “The villainy you teach me I will execute” Shylock What other plays, films or stories feature an outsider from a different cultural background? What role does the outsider play in creating dramatic conflict? Place yourself in the shoes of an Elizabethan playgoer. Does Shakespeare’s portrayal of Shylock or Othello, challenge the stereotypes you would have of race and religion, or does it reinforce them? Who are the outsiders in today’s society, can you find a modern equivalent for Othello or Shylock? How does the media portray the stereotype? How could a playwright get behind the stereotype? Other Stereotypes England of the 1590s had a lot to be thankful for. In 1588 it had managed to defeat the Armada sent against it by Phillip of Spain and in that victory had preserved itself both from foreign invasion and also a reversion to Catholicism as state religion. At the same time, all was not secure. England was at war with Spain in the Netherlands and there were 16 regular invasion alarms. Meanwhile, London was one of the most populous cities in Europe and as well as visitors, it was also home to sizeable communities of foreigners there by choice or compulsion due anti-Protestant persecution on mainland Europe. It is in this very precise context that Shakespeare's frequent stereotyping of foreigners needs to be understood. He lived at a time when to be a stranger from abroad in England was to be both a source of fascination and also some suspicion. And the most obvious way of dealing with such ambiguous feelings was to revert to laughter. Shylock is not the only character in The Merchant of Venice subject to satiric portrayal. In fact the presentation of the various international suitors seeking Portia is far more onedimensional than the rich representation that Shylock receives. Now you’ve read the play consider the following questions: Do you feel any sympathy for Shylock at the start of the play? Do you feel his anger towards Antonio is justified, albeit acting on this anger is deeply flawed? Do you feel that it is the loss of his daughter or his money that most disturbs him? Consider his reaction to the tale of Leah’s ring supposedly being exchanged for a monkey. Do you feel he is as much an old man as he is a Jewish moneylender? Old men seeking to lock up their daughters were a very common comic stereotype in Shakespeare's age. Do you feel any sympathy for Shylock forced to dine among the Christians while we know his house is being robbed - or do we just hope Jessica can get away? Do you feel any sympathy for Shylock when he is finally condemned and forced to convert to Christianity and hand over half of his wealth to the Venetian state? Do you feel that Shylock's enemies are morally superior or better people than him? Would they be found wanting if judged by Portia? Selection of Biblical references in The Merchant of Venice Abraham Patriarch of the Hebrew people. He’s a key figure in the history of both the Jewish and Arab peoples, as well as in the religions of Judaism, Christianity and Islam. He was the father of Isaac and also the father of Ishmael, from whom many of the Arab people are descended. Israelites are the descendants of Isaac’s son Jacob, whom God renamed Israel, and from Jacob’s son Judah come the terms Jew and Jewish. Barrabas In a final effort to have Jesus released, Pilate offered to let a prisoner go to indicate Rome’s goodwill toward the Jews during the Passover season. He offered them a choice between Jesus and Barrabas, a known murderer and robber. They chose to release Barrabas. Barabas is the name of the protagonist in Marlowe’s Jew of Malta which predates The Merchant of Venice by 6 years. 17