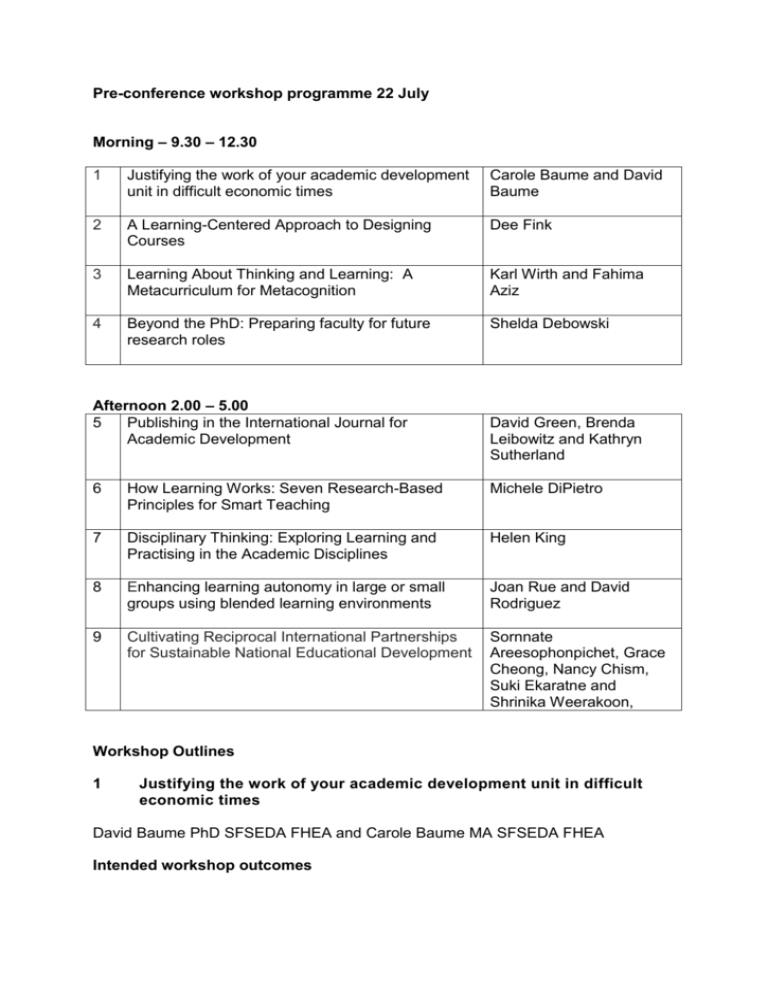

Pre-conference workshop programme 22 July

advertisement

Pre-conference workshop programme 22 July Morning – 9.30 – 12.30 1 Justifying the work of your academic development unit in difficult economic times Carole Baume and David Baume 2 A Learning-Centered Approach to Designing Courses Dee Fink 3 Learning About Thinking and Learning: A Metacurriculum for Metacognition Karl Wirth and Fahima Aziz 4 Beyond the PhD: Preparing faculty for future research roles Shelda Debowski Afternoon 2.00 – 5.00 5 Publishing in the International Journal for Academic Development David Green, Brenda Leibowitz and Kathryn Sutherland 6 How Learning Works: Seven Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching Michele DiPietro 7 Disciplinary Thinking: Exploring Learning and Practising in the Academic Disciplines Helen King 8 Enhancing learning autonomy in large or small groups using blended learning environments Joan Rue and David Rodriguez 9 Cultivating Reciprocal International Partnerships for Sustainable National Educational Development Sornnate Areesophonpichet, Grace Cheong, Nancy Chism, Suki Ekaratne and Shrinika Weerakoon, Workshop Outlines 1 Justifying the work of your academic development unit in difficult economic times David Baume PhD SFSEDA FHEA and Carole Baume MA SFSEDA FHEA Intended workshop outcomes Participants will have begun to plan how they will strengthen the case for their academic development work, through setting goals and evaluating their achievement. Participants’ plans will address: Current and likely future university and national priorities; Current and necessary institutional capabilities and commitments; and What is known about how students learn and how staff change their practices Workshop design and timetable Participants will be both active and interacting for the great part of the session, on a series of structured tasks leading directly to the intended outcomes of the workshop. The workshop will make use of some of the ideas contained in Baume, D. (2008). A toolkit for evaluating educational development ventures. Educational Developments. 9: 1-7., http://tinyurl.com/ycqwpqd and the Evaluation Framework developed for the Higher Education Academy http://open.jorum.ac.uk/xmlui/handle/123456789/11220 00.00 – 00.10 00.10 – 00.30 00.30 – 01.00 01.00 – 01.30 01.30 – 01.50 01.50 – 02.10 02.10 – 02.30 02.30 – 02.40 02.40 – 02.50 02.50 – 03.00 2 Welcome and introductions to participants and facilitators Goals and evaluation in academic development Individual and small groups – What are the main goals for your unit’s academic development work? Paired co-consultancy to refine your unit’s top three goals against: Current and likely future university and national priorities; Current and necessary institutional capabilities and commitments; and What is known about how students learn and how staff change their practices Refreshment break and viewing participants’ goals Monitoring and evaluation, focussing on return on investment In pairs, planning to monitor and evaluate achievement of your unit’s top three goals Call back of some plans Revision of plans Evaluation of workshop – what ideas and practices from this workshop will you take into your academic development work? A Learning-Centered Approach to Designing Courses Dr Dee Fink, Dee Fink & Associates Abstract As caring teachers, we want our students to experience valuable kinds of learning in our courses. This workshop will introduce participants to a learning-centered approach to designing courses. In the workshop, we will go through the actual steps of designing a course: formulating significant learning outcomes and then integrating those outcomes with appropriate learning and assessment activities, etc. By the end of the workshop, participants will know how to design courses that lead to greater student engagement and better student learning. Description This design method is based on the work of L.D. Fink (2003, 2009). His original book has been translated into 4 languages. In addition, a synopsis of these ideas, called the “Self-Directed Guide for Designing Courses for Significant Learning” (35 pp., translated into 5 languages), will be available copyright-free to all workshop participants. The cores ideas of Fink’s model of “Integrated Course Design” are illustrated in the following diagram: Learning Outcomes Teaching & Learning Activities Feedback & Assessment Situational Factors Session objectives/learning outcomes: This workshop has one general objective: that by the end of the workshop, participants will be able to design high-quality, learning-centered courses. During the workshop, participants will practice applying each step of this process, namely: Identify and take into account important Situational Factors, e.g., class size, prior student knowledge, etc. Formulate significant learning outcomes, Identify the learning activities and assessment activities that are needed for each of their learning outcomes, and Integrate the learning and assessment activities into a time-sequence that builds on students’ previous knowledge and on preceding course activities. People who attend this will workshop will leave with two important “take-aways”: They will understand the principles of learning-centered course design that they can then use to design any course in the future, and they will have completed much of the work of designing one course of their own during the workshop, using a learningcentered approach. Session activities: The workshop will begin by looking at the important role of course design in the overall act of teaching. Then participants will engage in a “Dreaming” exercise in which they visualize what they really want their students to learn. Then we will go through all the primary steps in Fink’s model of Integrated Course Design. In each step, participants will actually do the work of writing significant learning outcomes, identifying appropriate learning activities, etc. The workshop activities will alternate between “whole group” and small group activities. The small group activities provide a means of generating focused dialogue and feedback on the work involved in high-quality design of courses. References: The ideas and examples introduced in this workshop come from two main sources: Fink, L.D. (2003). Creating Significant Learning Experiences: An Integrated Approach to Designing College Courses. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Fink, L.D. and Fink, A.K., ed. (2009). Designing Courses for Significant Learning: Voices of Experience. Issue #119, Fall 2009, in Jossey-Bass’ quarterly series, New Directions for Teaching and Learning. 3 Learning About Thinking and Learning: A Metacurriculum for Metacognition Karl Wirth (Macalester College) and Fahima Aziz (Hamline University) Session Objectives/Learning Outcomes The overall goal of this session is to introduce workshop participants to examples of activities for improving student metacognition. Expert learners are characterized by having deep knowledge about learning tasks, and about themselves as leaners (metacognitive knowledge). They are also adept at modulating their thinking and affect (self-regulation) while learning. Evidence also indicates that metacognition is needed for transfer, problem-solving, and for independent learning. However, several studies have shown that many students are unaware of their metacognition, or that their metacognitive knowledge and skills are relatively undeveloped. Numerous researchers have argued that students need to encounter explicit instruction on metacognition in many different disciplines. The challenge for instructors is to help students develop their metacognitive knowledge and skills within the context of disciplinary content. This workshop offers participants an opportunity to learn about activities that can be implemented in courses at any level, and in any discipline. Specifically, upon completion of the workshop, participants will: understand the fundamental elements of metacognition be familiar with a variety of activities that can be used to improve students’ metacognition, and be able to design and implement learning activities that target specific parts of metacognitive knowledge and control Session Activities The workshop will include instructional, small group, and individual reflection elements, planned as follows: Short, small group discussion of the goals of higher education (15 mins) Presentation providing background on theory of metacognition (30 mins) Individual reflection and small group discussion of important aspects of metacognition that could be improved with instruction (15 mins) Break (10 mins) Mixed presentation and small group work examining data and student work from examples of learning activities that target different elements of metacognitive knowledge and self-regulation (80 mins) Individual reflection and planning (15 mins) Whole group reflection and wrap-up (15 mins) 4 Beyond the PhD: Preparing faculty for future research roles. Professor Shelda Debowski, Ph.D., The University of Western Australia Workshop description In recent years universities have been more focused on encouraging high performance across the academic community, particularly with respect to research. This has required a closer look at how research capabilities and capacity are being developed within universities. Previous research has revealed that Ph.D. graduates move into academe with limited skills in project management, team building, grant writing and leadership. Recent initiatives across many different nations are working to address these gaps, resulting in a range of interventions and initiatives that would be of interest to other universities and nations. This workshop will first report on the outcomes of a six-week Churchill Fellowship to of the United Kingdom, United States and New Zealand, where various university representatives and higher education groups shared their perspectives on how researcher capacity and capabilities could best be encouraged. Following this, participants will have the opportunity to consider some of the good practice ideas that have emerged from the study tour and to discuss how they might be integrated into their own University practices. They will receive an information pack summarising the key strategies and methodologies being employed. The workshop will explore the implications for hosting these initiatives, and in preparing educational developers for these roles. The educational or academic development theme of the workshop. The workshop will reflect the broad theme of enhancing educational development The intended learning outcomes for the participants By the conclusion of this workshop participants will have: identified innovative strategies to support research capacity building and capability enhancement; shared practical and innovative approaches that are employed in their own universities; mapped the gaps in their current university support and discussed how those areas might be addressed, and examined the possibilities for collaboration with other educational development service areas within the university. The timetable of the workshop and the educational strategy for its design. Timing 10 10 – 30 30 - 40 40 - 70 75 - 125 Activity Introduction and discussion of participant contexts A review of the Churchill Fellowship findings, and implications for educational development Questions and discussion Group discussion: How does this compare with our universities? (Will include a full group debrief.) Group exercise: Using the provided handout, participants will examine a listing of the practices identified during the Fellowship, ranking those they see as most valuable. They will then move to a group that wishes to work on one of those approaches. In their newly formed groups, they will discuss one specific approach and how it might be introduced into their own universities. Members will be encouraged to share their own experiences and insights to further develop an understanding of the option.. 125 - 140 140 – 170 170 – 180 5 This part of the session will conclude with a review of the key strategies and the findings from each table. (The information from this part of the session will be collated and shared back to participants following the workshop.) Break Implications for educational development practice In this part of the session the participants will explore the implications of these enhanced practices on the role, placement and expectations of educational developers. They will be encouraged to explore related issues such as: learner outcomes, organisational structure and implications, political barriers and collaborative opportunities. Reflections from participants Four participants will be asked to share their reflections on the workshop and any issues they will need to explore on leaving the conference. Publishing in the International Journal for Academic Development David Green, Brenda Leibowitz and Kathryn Sutherland Abstract: Educational development is a growing academic field worldwide with a diverse theory base to reflect the multi-disciplinarity of developers. Many developers want to join this research dialogue with their own contributions, but find the idea of writing and publishing on the Scholarship of Educational Development (SoED) an unclear process. In this interactive pre-conference workshop, we will guide you through the publication process with ICED’s peer-reviewed International Journal for Academic Development, based on our experience as IJAD co-editors. We’ll help you explore: how IJAD differs from other higher education journals; framing your proposal; preparing a strong manuscript; making your reviewers’ tasks easier from the outset and how to responding to their feedback positively; maintaining good relationships with your IJAD editor; ealing with the technology that supports IJAD’s work. Throughout the workshop, you’ll be developing concrete plans for your own research project and you will end with an action plan for the next four weeks of productive writing. Learning outcomes: By the end of this session, participants will have: (1) Differentiated between the scope of IJAD and other forms of higher education scholarship; (2) Formulated a project proposal for IJAD; (3) Walked through IJAD’s peer-reviewed publishing process to help you plan your writing project; (4) Undertaken to be held accountable – and hold another participant accountable – for making progress on a research project to be submitted to IJAD for peer review. References: Candy, P. (1996) Promoting lifelong learning: academic developers and the university as a learning organization. IJAD, 1(1): 7-19. Eggins, H., & Macdonald, R. (Eds.) (2003). The Scholarship of Educational Development. Buckingham, UK: Society for Research into Higher Education/Open University Press. IJAD (n.d.) Instructions for authors. Available online at: http://www.tandfonline.com/action/authorSubmission?journalCode=rija20&page=instructi ons 6 How Learning Works: Seven Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching Michele DiPietro, Kennesaw State University A tenet of learner-centered teaching is that learning is the litmus test of any pedagogy. Therefore, one of the most important contributions educational developers can offer is to explain the learning process to instructors. This interactive workshop is based on the book “How Learning Works: Seven Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching,” which synthesizes 50 years of research on learning from the cognitive, motivational, and developmental perspectives into seven integrated principles (Ambrose et al. 2010). The principles highlight how prior knowledge, the organization of knowledge, motivation, practice, feedback, developmental issues, classroom climate, and metacognitive skills can all facilitate learning–or hinder it. Following this workshop, participants will be able to: List and discuss the seven principles of learning Describe the supporting research and evidence Facilitate experiential activities to highlight each principle Generate pedagogical strategies to support learning. The workshop combines theory and practice. For every principle, we will start with activities that underscore the far-reaching implications it can have on learning. We will then highlight the underlying research, and collaboratively generate pedagogical strategies in accordance with the principle. We will spend about 20 minutes on each principle, leaving ample time to debrief how participants can use the activities in workshops on campus, adapt them for particular audiences etc. We will use reflective exercises (such as recalling particularly (de)motivating educational experiences), discussions of case studies that highlight some learning roadblocks, a developmental game (Reimers and Roberson 2002) to underscore the role of intellectual development, planning exercises to highlight the complexities of metacognition, and reenactments of landmark psychology experiments (e.g., the Stroop effect (1935) to highlight the role of automaticity in the development of mastery, chunking experiments to highlight the interaction between working memory and long-term memory, stereotype threat activations (Steele and Aronson 1995) that highlight the role of disruptive emotions on performance, Bransford and Johnson’s (1972) experiments on the role of organizing schema in meaning-making etc). References: Ambrose, S., Bridges, M., DiPietro, M., Lovett, M., and Norman, M. (2010) How Learning Works: Seven Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching. Jossey-Bass. Bransford, J. D., and Johnson, M. K. (1972). Contextual prerequisites for understanding: Some investigations of comprehension and recall. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 11, 717-726. Reimers, C., and Roberson, B. (2002) “Teaching critical thinking: An interactive game based on Perry’s scheme.” Paper presented at the 27th annual POD conference, Atlanta, GA. Steele CM, Aronson J (1995). "Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans" Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 69(5), 797–811. Stroop, John Ridley (1935). "Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions". Journal of Experimental Psychology 18, 643–662. 7 Disciplinary Thinking: Exploring Learning and Practising in the Academic Disciplines Dr Helen King, Head of Academic Staff Development, University of Bath, UK It has been argued that a discipline-based approach is paramount in faculty development so as to situate it within the academics’ community of practice (e.g Jenkins, 1996). However, it has also been suggested that pedagogy is mostly generic in nature and that there are very few disciplinary differences (e.g. Gibbs, 2000; Wareing, 2009). So if teaching principles are generic and students do not learn differently in different subjects, then how can generic or multi-disciplinary faculty development programmes best tap into the specific academic context that our participants are working in and feel affiliated to? In the UK and elsewhere, discipline-based faculty development takes place with faculty from the same or a cognate set of disciplines (e.g. the discipline element of the Higher Education Academy: http://www.heacademy.ac.uk/disciplines). This workshop will explore the concept of discipline-orientated faculty development, whereby the discipline background of workshop and course participants is acknowledged and utilised to enhance development activities within generic or multidisciplinary contexts. The approach taken is to support faculty in exploring their own disciplinary ways of thinking and practising. Recently, interest has grown in higher education in the ways in which experts think and practise (e.g. Threshold Concepts, Meyer & Land, 2003; Decoding the Disciplines, Pace & Middendorf, 2004; and, in Geoscience, the emerging field of Geocognition, Libarkin, 2006). Learning and teaching, then, becomes a journey from novice towards expert. In addition to acquiring factual knowledge, students must understand how this fits within the conceptual framework(s) of their discipline and organise it for retrieval and application (Bransford et al, 2000). This approach thus requires staff (experts) to make explicit, unpack and explain their disciplinary ways of thinking and practising in order to support the students’ learning of concepts, frameworks and discipline cultures as well as subject content. To do this they may also have to re-orientate their thinking back to when they were a novice in the discipline and remember what they struggled with or where there might have been particular moments of understanding (‘aha’ moments). This workshop will introduce and discuss the concept of discipline-orientated faculty development, will explore the notion of the expert-novice continuum and will introduce a number of Open Educational Resources (OERs: freely available online under a Creative Commons licence) created by and for faculty developers as part of a project addressing the idea of disciplinary ways of thinking and practising (http://discipinarythinking.wordpress.com). Intended Learning Outcomes. By the end of the workshop participants will be able to: Critique the concept of discipline-orientated faculty development; Evaluate their own approach to including an academic discipline element to faculty development activities; Discuss the concept of the expert-novice continuum in relation to academic practice and within faculty development; Experience different learning activities to explore disciplinary ways of thinking and practising; Discuss different approaches to learning, teaching and assessment in a variety of disciplines. Timetable and Design. This workshop will be highly interactive, drawing on the participants’ experience of faculty development and/or academic practice. 50 minutes: Introducing Discipline-Orientated Faculty Development 20 minutes: Welcome & Introduction / Icebreaker 20 minutes: In small groups (if large audience) – share experiences of disciplinebased / orientated faculty development 10 minutes: Feedback 30 minutes: The Expert-Novice Continuum 10 minutes: Introduction to the concept of experts and novices in relation to faculty / students, with specific examples from one discipline (Geoscience) 20 minutes: Questions and discussion (how can we use this concept to enhance faculty development: both in terms of getting faculty to explore their expert practice and for faculty developers to explore their own) 15 minutes: Comfort Break 60 minutes: 10 minutes: 40 minutes: 10 minutes: Resources to Support Discipline-Orientated Faculty Development Introduction to project An opportunity to participate in sample activities from the resources Review and feedback 10 minutes: Summary and Closing Remarks 8 Enhancing learning autonomy in large or small groups using blended learning environments Joan Rué, David Rodríguez, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Spain. This workshop is based on the proposition that quality in learning can be enhanced by combining learning in real and virtual contexts, when the student’s autonomous development is the foundation of the teaching intervention. Perceptions of learning environments and the experience of assessment are closely related to learning results and play a decisive role in how students approach their learning (Entwistle, 1991; Marton & Säljö, 1997). Although the context of learning is often taken to be non-problematic in educational institutions (Boud, Walker 1998), there are specific factors defining good learning contexts. According to Ramsden (1991), the key contexts which define "good teaching" in higher education are the teachers’ concern for and availability to students; the enthusiasm and interest of teachers; clear organization and goals; feedback on learning; the encouragement of student independence and active learning; an appropriate workload and relevant assessment methods; and the provision of a suitably challenging academic environment. The concept of learning environment underpins the importance of learning contexts, and it has a paramount importance in both student learning approaches and in their perceived self-efficacy (Jungert 2010). Complementary, academic self-efficacy has been positively linked to the use of strategy and self-regulation (Carless, et alt, 2011, Pintrich and De Groot 1990; Zimmerman and Schunk. 2004 Bandura 1997; Zajacova, Lynch, and Espenshade 2005). The workshop will be focused on three propositions: learning is a process that takes place within a reliable scaffolding (structuring) focused on the student’s approach, with a well aligned set of learning actions; the way different resources are deployed may enhance student autonomy and agency, and the capacity to be self-driving in his/her own learning process; a clear model aligned with virtual tools can allow teachers, without a special awareness about the importance of learning contexts, to develop their own proposals and facilitate their ability to build up their own scaffolding for their students’ self-regulation and learning enhancement. Learning outcomes Participants will: summarize in writing their reflections about engaging students in their own learning discuss the main conditional factors in developing autonomous learning recognize the main conditional factors in developing autonomous learning analyze some proposals from the proposed approach used in the model specify their own framework combining such approaches with the contents and requirements of some of their subjects. Timetable and educational strategy The workshop relies on active participation, through getting information, reflecting, proposing actions and discussing them, on the basis of both the participants’ teaching experience and the action model proposed in the session. Time 10’ 25’ Activity Workshop presentation: information Self-reflection about teaching purposes engaging students in their own learning 25’ Recognizing the main conditional factors of developing autonomous learning 35’ 45’ Action model (Rué 2010) Deciding and specifying further actions according a given subject framework and the enhancement of autonomous learning. Final discussion and workshop closure. 40’ References: Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman. Boud D., & Walker D. (1998): Promoting reflection in professional courses: The challenge of context, Studies in Higher Education, 23:2, 191-206 Carless, D., Salter, D. Min Yang & Joy Lam (2011): Developing sustainable feedback practices, Studies in Higher Education, 36:4, 395-407 Entwistle, N. J. (1991). Approaches to learning and perceptions of the learning environment. Introduction to the special issue. Higher Education, 22, 201-204. Jungert, T., & Rosander, M., (2010): Self-efficacy and strategies to influence the study environment, Teaching in Higher Education, 15:6, 647-659 Marton, F., & Säljö, R. (1997). Approaches to learning. In F. Marton, D. Hounsell, & N. Entwistle (Eds.), The experience of learning. Implications for teaching and studying in higher education [second edition] (pp. 39-59). Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press. Pintrich, P.R., and E.V. De Groot. 1990. Motivational and self-regulated learning components of classroom academic performance. Journal of Educational Psychology 82: 33_44. Ramsden, P. (1991): A performance indicator of teaching quality in higher education: The Course Experience Questionnaire, Studies in Higher Education, 16:2, 129-150 Rué, J., et alt. (2010) 'Towards an Understanding of Quality in Higher Education: The ELQ/AQA08 Model as an Evaluation Tool', Quality in Higher Education, 16: 3, 285 —295 Zajacova, A., S.M. Lynch, and T.J. Espenshade.. 2005. Self-efficacy, stress, and success in college. Research in Higher Education 46: 677_706. Zimmerman, B. J. & Schunk, D. H. (2004) Self-regulating intellectual processes and outcomes: a social cognitive perspective, in D. Y. Dai & R. J. Sternberg (Eds) Motivation, emotion and cognition (Mahwah, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates). 9 Cultivating Reciprocal International Partnerships for Sustainable National Educational Development Sornnate Areesophonpichet, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand; Grace Cheong, Singapore Management University, Singapore; Nancy Chism, Indiana University, USA; Suki Ekaratne, University of Bath, England; Shrinika Weerakoon, Colombo University, Sri Lanka Rapidly increasing opportunities for global communication and collaboration, coupled with new interest in improving performance in higher education, have led to a variety of partnerships between educational developers across and within national boundaries. As these have been enacted and assessed, developers have issued calls for those involved in partnerships to avoid a colonialist conceptualization (Manathunga, 2006; Lee, 2011). This session focuses on qualities in educational development partnerships that strive for more equal and meaningful interchanges. Situated in the cases of specific recent partnerships, the design calls for participants to explore the following questions: What qualities, such as reciprocity and sustainability, are important in effective international and national development partnerships? Which are essential to a postcolonialist approach? How are these qualities ensured for partnerships that are initiated when one party has expertise that the other is seeking? When resources for continuing the partnership are limited? What steps can partners take to cultivate reciprocity and sustainability as they design their partnerships? Intended Learning Outcomes for the Participants: 1. Deeper insights into the characteristics of reciprocal and sustainable exchanges 2. Increased familiarity with exchanges being enacted among developers 3. Generation of principles for future exchanges The Timetable of the Workshop and the Educational Strategy for Its Design: 1. 50 minutes – Interactive introduction of the themes (postcolonialism, reciprocity, collaboration, sustainability and other concepts defined) and description of selected instances of educational development exchange in facilitator’s experience. 2. 30 minutes-In groups, participants will exchange examples of international educational development exchange in which they have been involved and discuss the extent to which these were reciprocal and sustained. They will be asked to identify two instances for further sharing with the whole group. Each group will be asked to list its two instances on one of three flip charts: Highly reciprocal, moderately reciprocal, not reciprocal. They will also indicate with a plus or minus sign whether the exchanges were sustained after initial work was completed. 3. Break: 15 minutes. 4. 50 minutes—Debriefing will involve first listening to the reasons each group provides for the way in which members classified the exchanges they described, then attempting as a group to generate a list of characteristics of reciprocal and sustained exchanges. 5. 20 minutes—Group discussion of remaining questions: (see abstract above) 6. 15 minutes—Evaluation and concluding thoughts References Manathunga, C. (2006). Doing educational development ambivalently: Applying post-colonial metaphors to educational development? International Journal for Academic Development, 11(1), 19-29. Lee, V. S. (2011). Reflections on international engagement as educational developers in the United States. In J. Miller and J. Groccia (Eds.), To Improve the Academy. (Vol. 29, pp. 302-314). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.