Implementation of law in a horizontal perspective

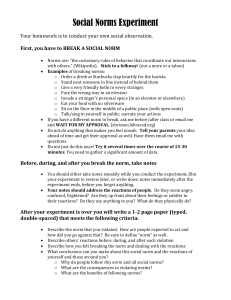

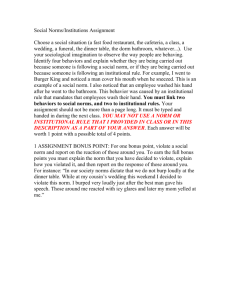

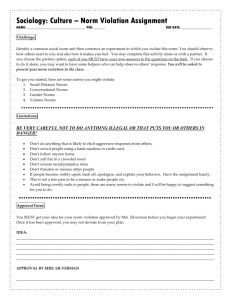

advertisement