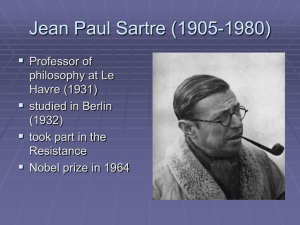

Jean Paul Sartre (1905-1968)

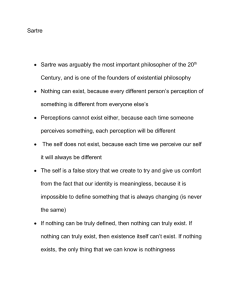

advertisement