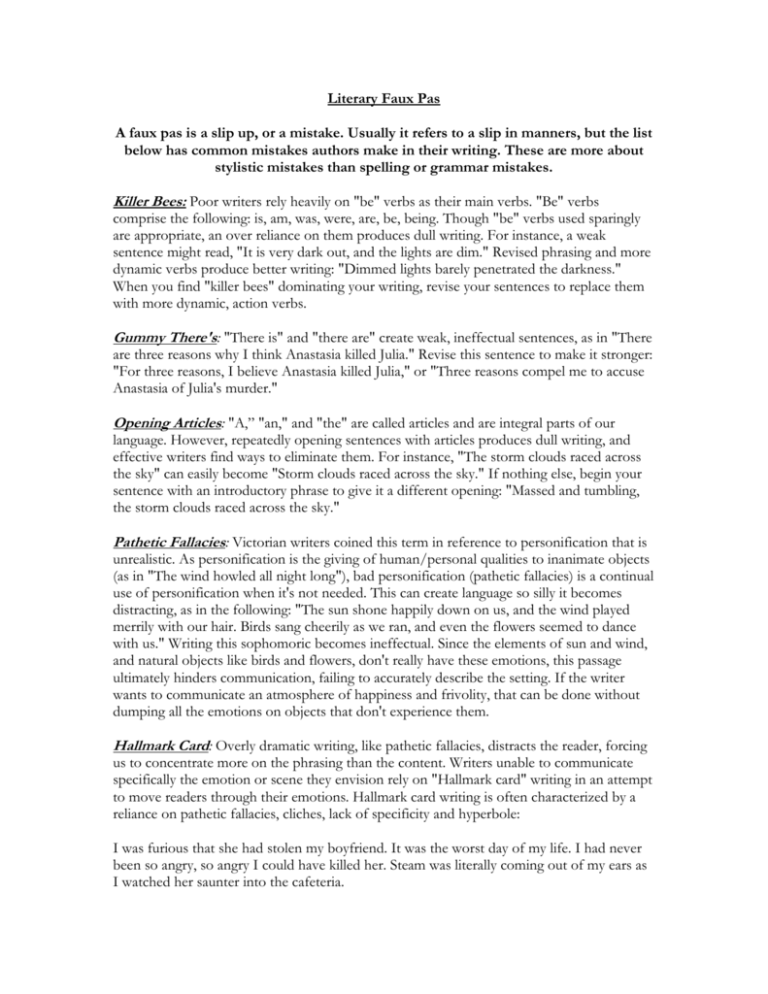

Literary Faux Pas

advertisement

Literary Faux Pas A faux pas is a slip up, or a mistake. Usually it refers to a slip in manners, but the list below has common mistakes authors make in their writing. These are more about stylistic mistakes than spelling or grammar mistakes. Killer Bees: Poor writers rely heavily on "be" verbs as their main verbs. "Be" verbs comprise the following: is, am, was, were, are, be, being. Though "be" verbs used sparingly are appropriate, an over reliance on them produces dull writing. For instance, a weak sentence might read, "It is very dark out, and the lights are dim." Revised phrasing and more dynamic verbs produce better writing: "Dimmed lights barely penetrated the darkness." When you find "killer bees" dominating your writing, revise your sentences to replace them with more dynamic, action verbs. Gummy There's: "There is" and "there are" create weak, ineffectual sentences, as in "There are three reasons why I think Anastasia killed Julia." Revise this sentence to make it stronger: "For three reasons, I believe Anastasia killed Julia," or "Three reasons compel me to accuse Anastasia of Julia's murder." Opening Articles: "A,” "an," and "the" are called articles and are integral parts of our language. However, repeatedly opening sentences with articles produces dull writing, and effective writers find ways to eliminate them. For instance, "The storm clouds raced across the sky" can easily become "Storm clouds raced across the sky." If nothing else, begin your sentence with an introductory phrase to give it a different opening: "Massed and tumbling, the storm clouds raced across the sky." Pathetic Fallacies: Victorian writers coined this term in reference to personification that is unrealistic. As personification is the giving of human/personal qualities to inanimate objects (as in "The wind howled all night long"), bad personification (pathetic fallacies) is a continual use of personification when it's not needed. This can create language so silly it becomes distracting, as in the following: "The sun shone happily down on us, and the wind played merrily with our hair. Birds sang cheerily as we ran, and even the flowers seemed to dance with us." Writing this sophomoric becomes ineffectual. Since the elements of sun and wind, and natural objects like birds and flowers, don't really have these emotions, this passage ultimately hinders communication, failing to accurately describe the setting. If the writer wants to communicate an atmosphere of happiness and frivolity, that can be done without dumping all the emotions on objects that don't experience them. Hallmark Card: Overly dramatic writing, like pathetic fallacies, distracts the reader, forcing us to concentrate more on the phrasing than the content. Writers unable to communicate specifically the emotion or scene they envision rely on "Hallmark card" writing in an attempt to move readers through their emotions. Hallmark card writing is often characterized by a reliance on pathetic fallacies, cliches, lack of specificity and hyperbole: I was furious that she had stolen my boyfriend. It was the worst day of my life. I had never been so angry, so angry I could have killed her. Steam was literally coming out of my ears as I watched her saunter into the cafeteria. First, steam never comes out of anyone's ears, literally or not. Second, relying on extreme statements is a weak attempt to manipulate the reader into caring for the speaker: it is highly doubtful that this was indeed the "worst" day of her life, and it takes a lot to actually murder another human being. Finally, this passage lacks details, simply informing us that the speaker was "furious" and "angry." Show not Tell: Great writing is characterized by specificity, supplying details that communicate clearly to the reader an exact image, emotion or thought. For instance, telling the reader "The pizza was delicious" communicates nothing. With no employment of the senses (appeal to taste, sight, touch, smell, sound), this passage fails to create in the reader's mind the pleasure of the pizza. This writer might well find her pepperoni pizza delicious, something that I--who find pepperoni not all that tasty--would disagree with; instead, I would envision my favorite, Canadian bacon and olives, and imagine a pizza far different from the one the writer is drooling over. Hence, she fails to establish in my mind the pizza before her. Look for details: the way pepperoni curls into a bowl, rimmed with black, filled with golden oil; the way cheese--usually mozzarella and cheddar--congeals in streaks of dark white and off-yellow, with occasional eruptions of grease; the way crust rises unevenly about the edges, a visual shading of golden brown to ash black. In short, don't TELL us the pizza was delicious: SHOW us. When you find yourself making summary statements, look for details. If the details aren't truly there to begin with, then you can't make your summary/telling statement anyway. Clinky Cliches: You've heard them: "It's not over till the fat lady_____"; "I was so hungry I could eat a ______";"I cried till my eyes turned _______." If you can complete these sentences, you've encountered cliches, phrases used so often they come to us automatically. That's the problem. Cliches aren't found in good writing; they're a substitute for good writing. Writers who rely on cliches tell the reader they can't think of the specific details that would more clearly pin down what they want to say; instead, they opt for a "tried and true" (another cliche) phrase. Cliches bore the reader and communicate your lack of specificity. Excessive Verbosity: Too many writers recreate the pauses in their thinking, using unnecessary phrases as if treading water. For instance, a sentence reading, "From what I could tell, his response was really exaggerated and completely unnecessary" swells with pointless adverbs and excess phrasing; this could be more simply stated: "His response was exaggerated and unnecessary." Long sentences have their place (witness the way Hawthorne crowds levels of thought in his extended clauses), but writers often confuse length with depth. If you can say the meaning simply, do so, and leave the longer sentences for your more intricate explorations of meaning.