The Ecumenical dimension of religion in Ireland

Topic 3.6 Religion in contemporary Ireland

The Ecumenical Dimension of Religion in Ireland

Please note that the following article is background information only on this topic. It in no way constitutes a sample or exemplary answer on this topic.

Student work

Ecumenism may be defined as ‘the promotion of worldwide Christian unity’ (Brodd,

2002, p245). J. R. Walsh describes ecumenism as ‘the movement in the Church towards the unity of all believers in Christ (Ephesians 4:21), and into which the Holy Spirit leads

(John 16:13). The term has its roots in the Greek word ‘oikoumene’ that means ‘the whole inhabited world’ (see Luke 2:1). While most Christians belong to one of the three main traditions of Roman Catholicism, Orthodoxy or Protestantism, others are members of smaller traditions (some of which challenge the very definition of what it means to be a Christian). Amidst such diversity there exists ongoing movement towards unity within

Christianity, particularly regarding doctrinal and institutional matters that have traditionally been a source of division. Many Christian denominations advocate ecumenism and Vatican II specifically called on Roman Catholics to engage in ecumenism:

‘The restoration of unity among all Christians is one of the principal concerns of the Second Vatican Council. Christ the Lord founded one Church and one church only. However, many Christian communions present themselves to [people] as the true inheritors of Jesus Christ: all indeed profess to be followers of the Lord but they differ in mind and go their different ways, as if Christ himself were divided’

Decree on Ecumenism, number 1

There is a wide range of diversity within the various Christian traditions yet most traditions look to Christ and to the Christian creed as their common cornerstone. Indeed

Jesus himself called for unity among his followers:

‘I pray not only for these [disciples] but also for those who, through their teaching will also come to believe in me. May they all be one, just as, Father, you are in me and I am in you, so that they also may be in us, so that the world may believe it was you who sent me’ (John 17: 20-21).

The first major schism in Christianity occurred in 1054 when Christianity became divided between East and West. The Eastern Orthodox Churches split from papal authority and leadership primarily over the issue of papal authority and appointed instead their own

Patriarchs at Constantinople, Antioch, Jerusalem, Rome and Alexandria.. They also disagreed with the Pope over the text of the Nicene Creed. A second schism in

Christianity occurred during the Reformation that began in the 1500s and led to the establishment of various protestant churches.

Protestantism has contributed greatly to the development of ecumenism in the twentieth century. In 1910 Protestants gathered from 43 countries in Edinburgh to form closer links

1

and acknowledged that the unity and fellowship in Christ that existed between his followers was stronger than their divisions. Protestantism was largely responsible for bible study groups, interdenominational cooperation in missionary activity and fellowship through the Student Christian Movement. The Patriarch of Constantinople sought cooperation among the churches in 1920. These endeavours created a climate which led to the foundation of international conferences on political, social and economic issues in

1925 and on theological issues in 1927. The World Council of churches (WCC) was established in 1948, consisting of 147 Orthodox, Protestant and Anglican churches.

Thereafter the Catholic Church took a growing interest in matters concerning interchurch relations.

In 1964 Vatican II issues its Decree on Ecumenism (Unitatis Redintegratio) which referred to non Roman Catholic traditions as ‘separated brethren’ but was careful not to imply that these were outside the Church or salvation. The decree also called for ‘the restoration of unity among all Christians’. The decree defined ecumenism as follows:

‘The term ‘ecumenical movement’ indicates the initiatives and activities encouraged and organised, according to the various needs of the Church and as opportunities offer, to promote Christian unity’.

Also in 1964 Rome witnessed a meeting between Pope Pius VI and the Ecumenical

(Oecumenical) Patriarch Athenagoras. The result was a revocation of the anathema between East and West, Constantinople and Rome, in 1965. In 1966 Pope Paul VI met with the Archbishop of Canterbury, Michael Ramsey, and established ARCIC with the intention of seeking ‘substantial agreement’ on theological matters leading to the unity of faith which Jesus desired. Agreed statements have emanated from the ARCIC commission e.g. 1971 Eucharistic doctrine, 1973 Ministry and ordination, 1976 Authority in the Church, 1986 Salvation and the Church and 1990 the Church as communion.

These statements point to the fact that there is much common ground between most of the

Christian traditions, the nature of Eucharistic sacrifice being of particular importance.

However, the ordination of women as priests in the Anglican communion is a matter that the Roman Catholic fundamentally will not engage in, since it has stated that it does not have the authority, on theological grounds, to ordain women as priests. Still, efforts at unity continue. In 1989 Pope John Paul II met Archbishop Robert Runcie of Canterbury and they recommitted both Churches to ‘the restoration of visible unity and full ecclesial communion’.

In Ireland in 1906 the Presbyterian and Methodist Churches established a joint committee to promote united approaches and increased unity between both denominations. In 1910 the Presbyterian Church and the Church of Ireland also stated their intention to cooperate in a united way. In 1923 the United Council of Christian Churches and Religious

Communions in Ireland was established. In 1966 their name was changed to the Irish

Council of Churches (ICC). Its members include the following churches: Anglican

(Church of Ireland), Presbyterian, Methodist, Lutheran, Moravian, Non-Subscribing

Presbyterian, Greek Orthodox, the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), The Coptic

Orthodox Church in Ireland, The Lifelink Network of Churches and the Salvation Army, and others. Since 1972 the council has had a full-time general secretary and Catholic and

Orthodox observers may sometimes join its biannual meetings. The Catholic Church is

2

not a member if the ICC or the WCC since it believes that Christ initiated only one

Church. It does however acknowledge that God’s grace can be found in other Christian churches and even in other world religions. The ICC has been united with the Irish

Commission for Justice and Peace (Roman Catholic Church commission) to promote peace and reconciliation in Northern Ireland. Together they sponsor a school’s peace education programme in Northern Ireland. Since 1973 their ecumenical initiative, the

Inter-Church Committee has met about every eighteen months in Dundalk. Members of the ICC and the Catholic Church have met annually. The purpose of such meetings is to dialogue on important ecumenical matters of concern such as the Church, scripture and authority, social and community problems, the sacraments of Baptism, Eucharist and

Marriage, Christianity and secularism, the Churches in the Gospels and in the writings of

St. Paul, youth work and the Churches and other matters. They have also promoted literature and videos which encourage inter-church dialogue e.g. Marriage and the Family in Ireland today, Reading the Bible Together, Salvation and Grace, Ecumenical Principles and Freedom, Justice and Responsibility in Ireland Today. They have also cooperated with members of the Catholic hierarchy to write reports on social issues e.g. drug abuse, the use of alcohol among young people, inadequate housing, violence, the environment, leisure, young people and the Church, and sectarianism. The work of ARCIC has been influenced by the outcomes of the ICC and indeed Irish theologians have been part of that international commission. In 1983 the Catholic Church revised its Code of Canon Law.

It continues to review the tension relating to the issue of mixed marriages. In part, this tension goes back to 1908 when the Catholic Church issued a decree (Ne Temere [Not rashly]) which insisted on the presence of a Catholic priest at any marriage between a

Catholic and non-Catholic. Protestants interpreted this decree as an effort by the Catholic

Church to ensure that any children of such marriages would be brought up in the Catholic faith.

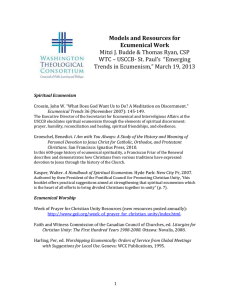

Ecumenism is also in evidence at the regular meetings between leaders of the four main

Churches in Ireland: Catholic, Anglican, Presbyterian and Methodist. At local level there is ongoing contact between clergy and laity, and ecumenical prayer services and carol services are not uncommon. In January each year there is a week of prayer for Christian unity. The first Friday of March is Women’s World Day of Prayer and is another occasion for ecumenical gatherings. In 1970 the Irish School of Ecumenics was founded making a significant contribution to adult education and academic research in the field of ecumenics. Other ecumenical endeavours include: Glenstal Ecumenical Conference,

Greenhills Ecumenical Conference and the Social Study Conference; communities such as Corrymeela, Currach, Cornerstone, Columbanus and Lamb of God community,

Christian Renewal Centre at Rostrevor, Protestant and Catholic (PACE) as well as local charismatice groups. Both the Catholic and Protestant Churches have provided funding for over 700 inter-church reconciliation projects in Europe.

Notwithstanding the many ongoing efforts to promote ecumenical dialogue, differences remain, many of them theological (e.g. Eucharist) which are proving difficult areas for

Christian unity. There has also been opposition to the ecumenical drive from fundamentalists, in particular protestant fundamentalists. This in part accounts for the growth in numbers of the Free Presbyterian Church founded in 1951by Ian Paisley.

3

Sources:

World Religions: A Voyage of Discovery, J. Brodd (2002) pp 240-245.

Religion: The Irish Experience, J.R. Walsh (2003) Veritas.

The New Jerusalem Bible, Darton, Longman & Todd (1990).

Decree on Ecumenism, (Unitatis Redintegratio), Vatican II.

Ne Temere (not rashly), Vatican II.

4