In Praise of Tohu va-Vohu

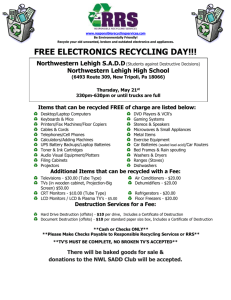

advertisement

Bar-Ilan University Parshat Hashavua Study Center Bereshit 5774/October 18, 2014 This series of faculty lectures on the weekly Parsha is made possible by the Department of Basic Jewish Studies, the Paul and Helene Shulman Basic Jewish Studies Center, the Office of the Campus Rabbi, Bar-Ilan University's International Center for Jewish Identity and the Computer Center Staff at Bar-Ilan University. For inquiries, please contact Avi Woolf at: opdycke1861@yahoo.com. 1090 In Praise of Tohu va-Vohu By Miriam Faust The first verse of Genesis deals with the creation of the world, the greatest act of creation of all time. The second verse describes the primal state of the universe prior to this act of creation: "The earth was unformed and void (tohu va-vohu), with darkness over the surface of the deep" (Gen. 1:2). Viewing the story of Creation as a model from which to learn about the human process of creating, it is interesting to examine whether a cognitive state of "unformed and void" relates to the processes by which human beings are creative. For example, everyone who creates might have to "break" and "disorganize" the familiar picture of the world in order to free himself from it and view reality in another way. Current research dealing with creative thought indeed supports this assertion and points to the need for a sort of tohu va-vohu, or a certain measure of what one might term cognitive chaos, in order to discover and create something new in all walks of human creativity. These findings associate the state of being Prof. Faust is Rector of Bar-Ilan University. "unformed and void" that preceded Creation with a universal human state which is a precondition for the ability to create. Creative thought is a supreme human characteristic that enables important achievements which further humanity in all areas and all times. This ability is relevant not only to great discoveries in science, art, music, medicine, technology and any field of human activity that changes the world, but also to the petty creativity needed in daily life in order to execute a task in a new way or solve unconventional problems that require insight and adapting to change. The great challenge of creativity is to overcome the natural human tendency to become fixated on a particular view of a situation and on the usual and familiar system of relationships among existing elements. Paradoxically, even though expertise (i.e., a broad and organized body of knowledge) in a certain field is a necessary precondition for significant creation, rigidity of thought, which acts adversely on creativity, is likely to be stronger in those areas in which a person has expertise, because of the tendency to adhere to known and familiar structures precisely in such areas. This difficulty finds expression in the phrases used to describe creative thought, such as thinking "out of the box" or "upside down"—dramatic concepts that reflect a drastic change in existing thought settings. Indeed, since creating requires innovation and originality, the creator must "mix" the relevant existing elements and create a cognitive chaos that will make the thought process flexible so that a new system of connections between things which previously had been thought to be unrelated can be built. The more daring the association and the more distant the things that are brought together, the greater is considered the creativity and the creator. Accordingly, current research that uses computational means to examine the associative networks of creative people in comparison with non-creative people points to creative people having a more "wild" and chaotic network of associations, which apparently enables them to connect ideas, thoughts, and concepts in an original and unconventional way. These findings fit in with associative theories of creativity, according to which the creative process is based on associative thinking in which distant associations are combined to form a new and applicable concept. People with high creative ability are capable of forming more associations, including weak and unconventional ones, for a given idea—a trait that enables them to draw together distant ideas more easily and to come up with creative solutions.1,2 The findings are also supported by brain scan studies, which show that systems in the brain which are thought to be involved with chaotic thinking, less subjected to the rules of reality, are more developed in creative persons.3 The associative chaos that makes it possible to sever oneself from something (such as the usual sense of a word), sometimes even doing away with one thing to create something new (such as a new metaphorical meaning), relates to the concept of tohu va-vohu found in Genesis. This pair of words has been interpreted by traditional exegetes (Rashi, Shadal, Ba`al ha-Turim, and Ha`amek Davar on Genesis 1:2) as wonderment, desolation, emptiness, fogginess, something mixed or disordered, and even destruction. These interpretations are directed towards the special nature of the state of tohu va-vohu and to the human reaction to such a state. When something appears void, its components lacking any familiar, clear and orderly presentation, the natural human reaction is likely to be one of unfocused, dumbfounded (= bohu) wonderment. As follows from the current research to which we referred above, precisely such a state is likely to give rise to new ideas and unconventional combinations. The notion that tohu va-vohu, including the breaking of an existing well-organized and familiar state, is a necessary pre-condition for creating appears in the writings of Ramhal:4 "The earth was unformed and void [tohu va-vohu]" for initially it was created, but then it was destroyed. That is, it was created full of evil, so that the evil in it came out and destroyed the earth itself, leaving no creature any existence. Then, afterwards, "G-d said, 'Let there be light,'" and the created things began to emerge one by one. 1 Faust, M., & Kenett, Y. N. (2014). "Rigidity, Chaos and Integration: Hemispheric Interaction and Individual Differences in Metaphor Comprehension." Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8; 511. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00511 2 Kennet, Y.N., Anaki, D., & Faust, M. (2014). "Investigating the Structure of Semantic Networks in Low and High Creative Persons." Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8; 407. Doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00407 3 Ritter, S. M., & Dijksterhuis, Ap. (2014). "Creativity—the unconscious foundations of the incubation period." Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8; 215. doi: 10.3389/fnhum .2014.00215 4 Rabbi Moses Hayyim Luzzato (Ramhal), KL"H Pitchei Hokhmah, Hayyim Friedland ed., Bnai Brak (1992), sect. 47' p. 170. It follows from Ramhal's commentary that the new world could be built and bestowed with light only after the previously existing, older frameworks that tied the world to a fixed state had been ruined and destroyed. Only then could one build it according to a new perception. Ramahal adds:5 There is no element of casting fear [Aima] in this Shattering [Shevirah], and from there comes the veritable destruction, that is, the tohu va-vohu. Likewise, from its awakening also came the flood, which brought actual destruction. But there is a difference between them, for in the flood the Shattering was not totally aroused, for there was something that remained, namely the ark, and accordingly the entire earth itself was not destroyed, but only a plough's measure. Aima in the Kabbalah is Bina or Understanding. When Understanding exerts its influence there is a tendency towards rigidity of thought, and therefore removal of Understanding is total destruction and is the precondition for new creation. In this regard Ramhal notes that the Flood did not bring utter destruction but only destruction on the surface, since the old constructs survived in the ark. By contrast, forming a totally new world, a new creation, required total destruction of all that existed previously. Ramahal's main point is that according to the Kabbalah tohu va-vohu was not the beginning of the world, rather the destruction of a stable state of existence that preceded it. Such an explanation supports the idea that something new cannot come out of a delimited reality. The existing must be destroyed, a certain degree of chaos, of tohu va-vohu, must be created, and then something truly new can be initiated. A similar idea was presented by Rabbi Zaddok Ha-Cohen of Lublin:6 The gemara (Sanhedrin 26b) asks, "why is it [the Torah] called Tushiyah?7...Because it is composed of words, which are immaterial (tohu), upon which the world is founded (shutat)." Rashi explained this [immaterial words] as mere speech sounds; and speech is entirely something that cannot be touched, just like this tohu. Or perhaps consider what is said (in 5 Ibid., p. 201. 6 Rabbi Zaddok ha-Cohen of Lublin, Pri Tzedek on the Torah, Parashat Devarim. Lublin ed., 1934, p. 16. 7 What follows is an interpretation of Isaiah 28:29: "That, too, is ordered by the Lord of Hosts; His counsel is unfathomable, His wisdom is marvelous" (…hifli `etzah higdil tushiyah). Genesis Rabbah 2.2), that the earth being tohu va-vohu was "like a king who had two servants, etc. The earth sat bewildered and astonished (= tohu vavohu), saying, 'The celestial beings…,'" interpreting tohu as wonderment. Likewise, here we have words of tohu, meaning that no one understands how it came to him, that it fell into his mind and made him so fortunate as to direct his thoughts towards the Halakhah taught to Moses at Mount Sinai; and this is the sense of "His counsel is unfathomable, His wisdom marvelous." This passage, as well as its continuation, expresses the idea that innovations in Torah and Halakhah are based or founded on an initial state of tohu; in other words, even creative ability in Halakhah requires a certain degree of chaotic thinking, expressed by wonderment (tehiyah) and astonishment (behiyah). Thus, the very first two verses of the Torah, dealing with creation of the world out of tohu va-vohu, contain a deep insight into the ability to create—the human capability which symbolizes, perhaps more than anything else, the creation of man in the image of G-d. These verses teach that what we perceive as most threatening and negative of all—a state of chaos—may be precisely what is necessary for creating something new and better. Translated by Rachel Rowen