Perspectives on a Course on the History of the Automobile and

advertisement

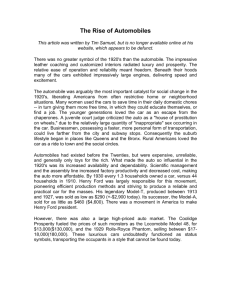

Perspectives on a Course on the History of the Automobile and American Life John A. Heitmann Alumni Chair in Humanities and Professor of History University of Dayton Dayton, OH 45469-1549 Symposium: The Automobile in Our Culture Youngstown State University, April 26, 2008 Work-In-Progress: Do Not Cite or Quote Without Permission Beginning in the fall of 1998, I began teaching the history of the automobile. This decision was result of a passion going back to childhood, coupled with a desire to design a course that students possessing a wide spectrum of ability and motivation would become engaged. What motivated me at mid-career to shift first my pedagogical, and then subsequently my writing and research priorities? Perhaps it was a sabbatical and a Porsche 911 restoration project that sparked this transition, or boredom with the history of science and technology courses that I had taught for the previous 15 years at the University of Dayton. Most certainly I was interested in teaching a course that could serve as a broad window into the recent past, one with considerable power to explore areas of the history of technology, as well as economic and social history. What I did not realize in 1998 however, was that my ongoing effort to improve this offering would lead me into the area of cultural history as well, of which I knew precious little about. Indeed, over time the course would shift its focus, as film, music, and literature displaced the more well-worn topics related to technology and business history. Initially, my auto and American life course was taught as a senior history seminar, a course for majors that met once per week for about three hours. Primary objectives included that: 1) this would be a shared learning experience, quite different from other history courses, in that enrollment was limited to 15 majors, in contrast to the normal history class of 35; 2) this was a capstone offering, and thus was to demand considerable analytical, research, and communicative skills; and 3) the primary goal of each student, no matter what one’s ability, was the creation of new knowledge. Course requirements centered on a research paper (40%), with additional grades coming from discussion (25%), a book review (20%); and in in-class report of a book that I had identified as important to the field of auto history (15%). There were many challenges in starting off, the foremost of which was my own lack of formal knowledge concerning automobile history. While my training was in the history of science and technology, my specialization was in the history of chemistry and chemical technology, and what little I did know about auto history was derived from my teaching of a course in the history of American technology and its social consequences. Thus, I had to embark on a long and largely self-directed intellectual journey, of which I am now in my tenth year. My initial foundation for the course was therefore based not on my own scholarship, but on James Flink’s Automobile Age, supplemented by a book I had previously used with great success in my history of American technology class, Ben Hamper’s Rivethead. Since my second Ph.D. field had been American Economic and Business History, I remained on solid ground by assigning books for reports that were in that field: Ray Batchelor’s Henry Ford, Mass Production, Modernism and Design; Alfred Sloan’s My Years with General Motors; Stuart Leslie’s Boss Kettering: Wizard of General Motors; John Delorean’s On a Clear Day You Can See General Motors; Lee Iacocca’s Autobiography; Robert Post’s High Performance: The Culture and Technology of Drag Racing; Donald Critchlow’s Studebaker: The Life and Death of an American Corporation; James Ward’s The Fall of the Packard Motor Car Company; Eric Taub’s Taurus: The Making of the Car that Saved Ford; and finally Joe Sherman’s In the Rings of Saturn. To be sure, there were a number of books assigned that did explore broader sociological themes, and they included David Gartman’s Auto Opium; Warren Belasco’s Americans on the Road, Clay McShane’s Down the Asphalt Path; Virginia Scharff’s Taking the Wheel and Jane Holtz Kay’s Asphalt Nation. These works were most significant to furthering the student’s awareness of the power of technology in shaping everyday life, and conversely, the subtle choices that members of a society make concerning a technology. The oral report was significant for several reasons, and it often was the best early indicator in the class of individual student abilities. Students were expected to spend about half the 30-40 minute time on a critical summary of the book, with the second half raising questions about the author’s use of sources, methodology, and contribution to the understanding of automobile’s place in American life. The best students often came prepared to present Powerpoint presentations reflecting the main thrust of the book they were reporting on; the weakest uncritically summarized blow-by-blow the monograph’s contents, resulting in deadening boredom. To ensure that questions were asked by other students after the presentation was over, I required each student to write down three questions that they could ask of the speaker. At the conclusion, I randomly chose two or three students to ask their questions, although I opened the floor to all at the end of the talk. With a meaningful percentage of the grade allocated towards discussion, thoughtful responses could make or break a student’s final grade. In my first try, what little cultural history was in this first try was reflected in film. Previous courses of mine in the history of science and technology often incorporated film to effectively break up a class period, as well as to help students visualize three dimensional technologies that were also aesthetic in design. Film was thus employed to 1) raise issues of self-identification and individuality, as in the case of Harold Blank’s art cars in “Wild Wheels,” or spiritual sensibilities in “Pow Wow Highway;” 2) explain technology, as described in “The Secret Life of the Car;” 3) explore social issues, as in “Roger and Me,” or “Taken for a Ride;” and finally 4) deal with gender in the case of “Thelma and Louise.” While to date I have shown only clips of these films in class, I plan to place selected films on Flyer cable TV, so that students watch the entire film without taking away from class-time. Re-running clips for emphasis and discussion will follow. The unique place of the car in our lives, and the psychological aspect of the automobile were explored during the first class, as students were asked to write autobiographies that were then shared with others in the class. What do our cars tell us about ourselves? This was a critical exercise—and an icebreaker-- related to my objective of creating a shared learning experience. The question is as follows: For most Americans, the automobile is inevitably woven into our lives. Write a short “auto-biography” describing the relationship that you have had with one particular car. For example, you may recount memorable episodes in your life that featured the automobile, or describe feelings that you have had towards this machine. In your opinion, to what degree are automobiles appliances, and in contrast, special objects deserving love, hate, or other emotions? This assignment pointed out a fundamental paradox concerning the automobile in American life, namely that this lifeless steel, plastic and rubber artifact derived from mass production could take on a name and a personality of its own. And while generational differences exist, and this younger generation often views the car as another appliance, the number of students who share values related to the automobile with their fathers is rather remarkable. As mentioned previously, I wanted my students to have an educational experience that was memorable in every respect, and thus I also arranged for a series of field trips. For a museum experience, we visited The Citizen’s Motorcar Museum in Dayton, a Packard Museum set in a 1930s auto showroom. A second visit was made to a private Porsche Collection in Dayton, known as the Taj Garag. There was also an optional Sunday at he the Dayton Concours, with a written assignment for extra credit.And finally there was a Friday night out to Kil-Kare Speedway in Xenia, where students could sit next to locals who were missing 1/3 of their teeth, and experience modified stock cars crashing into the wall near where they sat. What was behind all of this, however, was a serious academic enterprise, one in which the place of technology in modern life was investigated in detail, and where 20th century history was reinterpreted from the perspective of perhaps the most significant economic enterprise of the period. Social consequences were in tight focus, as opposed to the far broader discussion of American technology that I had taught previously. Since that first 1998 offering changes have taken place not only in terms of focus away from business history towards far more cultural aspects, but also format, as variants have been taught in terms of; 1) a small scale seminar to first year students, and 2) a large class with majors across the board from business to engineering. From my perspective, as I learned more about automobile history, I increasingly moved into areas that I felt had not been fully explored or well synthesized, and that meant not only moving into topics involving film, music, and literature, but also writing about these relatively uncharted areas. What that also meant that I was leaving the firm ground of business and economic history and into areas of cultural history that were far more slippery, subjective. It often led to analysis on my part that was far from definitive and satisfying to someone like myself, who likes the concrete rather than the abstract. In terms of the films I used in the second and third iterations that were new to the course were the following: “Horatio’s Drive” “The Wild One” “Rebel without a Cause” “American Graffiti” “The Vanishing” “The Vanishing Point” “Christine” “Easy Rider” “Who Killed the Electric Car?” These additional films represented a mix of historical, documentary, and artistic media. They were used for a variety of purposes: to raise critical awareness concerning important issues; to provide historical context so that students could better understand a period; and finally, to view iconic films that helped define American cultural life. The use of these films resulted in another pedagogical problem, however. Namely, there are few good synthetic readings on cars and culture. The most significant anthology on the topic, edited by David Lewis, was published in 1982, more than 25 years ago. A second compendium of articles on car culture, Autopia, published in 2001, contains several essays on film that are simply impenetrable for students (and for any normal, educated person!). I thus embarked on writing my own text for this course, the subject of another discussion, but significant since Flink’s Automobile Age avoids discussion of film, music and literature. Note also that by 2004 I began including towards the end of the course topics related to the motorcycle. Again, this was a reflection of my own interests, particularly in the emergence of Rolex bikers and women and the meaning of all of this to American life. To that end, I included Brock Yates perceptive Outlaw Machine as required reading supplemented by by the two fine films “The Wild One” and “Easy Rider,” both of which demand considerable analysis and interpretation. This inclusion also opened the door for students to write a number of very fine research papers, on topics that included the globalization of Hell’s Angels and the FBI and Hell’s Angels. Interpreting the link between music and the automobile was perhaps my greatest challenge. Indeed, I began exploring the topic by reading material on the origins of Rock an’ Roll, and listening carefully to Howl’n Wolf, Chuck Berry, Elvis, Bo Diddley, and others. Ultimately the following songs were played in my classes: Lost Highway – 1949 Rocket 88 – 1951 Maybellene – 1955 No Money Down – 1956 Beep Beep, 1958 Hot Rod Lincoln – 1960 Hey Little Cobra – 1963 Dead Man’s Curve – 1964 G.T.O. – 1964 No Particularly Place to Go – 1964 Mustang Sally – 1966 On the Road Again – 1968 Gasoline Alley – 1970 Radar Love – 1973 Low Rider – 1975 One Piece at a Time – 1976 Devil in My Car -- 1980 In 2005 the classroom format for this offering was broadened to a general education upper level history course that had 35 students representing engineering, business, and a smattering of other majors. Clearly, a shared learning experience was no longer possible, and now lectures and tests were in order. And while film and Rock n’ Roll were still featured, the course now had a less personal and more traditional structure. As in all my courses, chronology, time, and cause and effect are central. Essay questions on the mid-term and final included the following: One observer on American History has commented that the United States found in the automobile a perfect technological expression of its personality, and its quest to level class, time and space. Critically discuss this statement, making sure to include the work of Henry Ford, Alfred Sloan, and Lee Iacocca. Without doubt the introduction and diffusion of the automobile during the first half of the 20th century resulted in enormous social change in America. Discuss the impact of the automobile on the American family, making sure to include: perceptions from the religious community; intergenerational conflict; courtship and mating; the place of women in the family; and finally, changes in home architecture. The automobile has had a profound impact on American culture. Discuss the place of the car in modern music and film, referring to what you heard and saw in class. What are some of the major themes associated with these cultural manifestations? Despite dire predictions concerning the “death of the car” written in the early 1970s, in 2005 the automobile continues to play an integral role in American society. Discuss current thoughts on the future of the car, drawing on the assigned writings of John Tierney, Ted Fishman, and Clive Thompson. How are American consumer preferences shaping modern automobile technology? The last addition to my auto history courses have been in the area of poetry. Impressed by the use of poetry in a team-taught course that I lead on “Cities and Energy,” I first wrote a paper on women poets, sexuality and the automobile that was presented that professional conference in 2007. I later extended this work to include poetry in general, with the intent of demonstrating to students that poets can see what we normally do not see or feel, until it is pointed out to us. It is the poets who have had something to say about what has been rarely said about human activities in and around cars. Their responses, particularly in writings after 1980, have resulted in a spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings, and a reconstruction of past events markedly distinct from that by historians employing textual sources. Lynne Knight’s poem “There in my Grandfather’s 1953 Green Buick” is one example of a poem read in class: He was touching me where no one had touched me before, there, in my grandfather’s old green Buick that wouldn’t go in reverse, so all the while I was worrying how he’d get the car turned around and headed back to his school, there as we were under the dark pines … I worried he’d scrape the paint against the pines and then he whispered We have to stop Do you know why we have to stop and I nodded, … and we slipped past the pines with our headlights still out and when we got there, I slid behind the wheel and drove down the mountain knowing something had happened I couldn’t reverse anymore than I could the Buick, knowing I wanted it, no matter what the nuns said, I wanted it, I could feel my body wet and alive as if there had been a birth.i Knight later stated that the poem “Pretty much encapsulates my sexual experiences as a teenager although it probably makes me sound a little more sexually aware than I actually was. There was a fierce desire, yes, but also lots of blind fumbling.” ii In sum, it is this cultural history that best explores the relationship between what it means to be human and the automobile. In that regard this course in automobile history addresses a fundamental thematic component of General Education at the University of Dayton , and thus is as significant to the education of our students as a traditional course emphasizing the political and social history of post-World War II America. It is not a substitute for an survey university history that serves to foster historical literacy. Rather, “The Automobile and American Life” probes far deeper into issues that enhance the understanding of the human experience and our contemporary world. Lynne Knight, “There in My Grandfather’s Old Green Buick,” in Brown, p.56. First published in Poetry East, Spring, 1992. On Lynne Knight’s education, awards, and poetry, see www.lynneknight.com. ii Lynne Knight to the author, March 16, 2007. i