Jenny Brown

advertisement

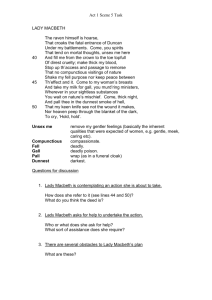

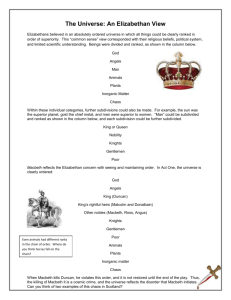

Brown 1 Jenny Brown ENGL 472-01 Scholarly Essay 5/3/01 “Blood will have blood”: Female Deviance and Male Violence in Macbeth William Shakespeare’s Macbeth is often interpreted as a tragic tale of a fallen hero destroyed by the power of feminine evil. An analysis of the play’s frequent concern with “manhood,” however, suggests that Macbeth interrogates cultural definitions of masculinity that associate it with aggression, violence, and bloodshed. In much of the earlier criticism of the play, the female characters in Macbeth are portrayed as the motivators of evil and are therefore defined as deviant. However, they are labeled as such when they exhibit male characteristics. They are blamed for the men’s perils, and seen as witches, who obstruct all that is right and good in patriarchal society. Yet the male characters in Macbeth are extremely violent, and they achieve their ambitions and their fullest definitions of themselves as men through acts of bloody aggression. Shakespeare’s Macbeth criticizes the cultural norm that describes masculinity as violent, ambitious, and aggressive by having the most “evil” characteristics among the females be decidedly male, and by showing the devastating consequences when a society embraces a concept of manhood grounded in violence. Macbeth’s extreme ambition accepts the “supernatural soliciting” in the three Weird Sisters’ prophecies (1.3.130). He has already thought of murdering Duncan in his violent ambition before they tell what “cannot be ill, cannot be good” (1.3.131). When he says “nothing is but what is not,” Macbeth shows how only “unreal imaginings” have any reality for him (1.3.143, footnote). Thus, the thought of killing his king is actually quite feasible to him. Macbeth states, “Time and hour runs throughout the roughest day,” Brown 2 expressing his determination to become king of Scotland and his belief that his plans will know fruition no matter what should transpire (1.3.149). This is an indication of his obsessive desire to gain the throne; he will wear the crown through any means possible, as “the greatest is behind” (1.3.118). Many critics focus on the psychological aspects of this play, claiming that Macbeth is weak, insecure, and overpowered by the females’ vexing nature. He is, indeed, morally weak in his hunger to wear the borrowed robes. Macbeth thinks Lady Macbeth and the Weird Sisters validate his secret thoughts of murdering Duncan simply by voicing them. Macbeth does not question the evil of killing beforehand because society has mentally shaped his adeptness in justifying his actions. Therefore, Macbeth is “ready to receive [the Weird Sisters] when they come to him” (Williams 154). His violent nature confirms his manhood in society, but his ambition overpowers his camaraderie with other men. Male violence rules the culture and blood lust begets tyranny in Macbeth. Howard Felperin assesses that Macbeth has in fact “long since internalized his society’s way of seeing and thinking” (171). In Act five, scene eight, Macbeth spouts violent epithets and exhibits his ingrained violence: “But swords I will smile at, weapons laugh to scorn” (5.7.13). He proclaims the necessity for his violence in stating, “While I see lives, the gashes/Do better upon them” (5.8.2-3). Macbeth displays his courage in fierce battle (5.8.34). His ambition causes him to believe he is valiant—“What man dare, I dare” (3.4.100). In this daring, he tries to prove his masculinity through blood lust. He believes violence proves his bravery and fullest masculinity. He has skillfully and wholeheartedly adopted the violent norms of his culture, but to a self-destructive extreme. Brown 3 For the society represented in Macbeth, “murder is what makes you feel like a man” (Orgel 146). The blood lust in the play is visible during Duncan’s rule, which was “utterly chaotic, and maintaining it depends on constant warfare [; . . .] the primary characteristics of his rule, perhaps of any rule in the world of the play, is not order but rebellion” (Orgel 146). The play’s blood lust thrives on ambition and desire, and “to act on desire [and kill] is what it means in the play to be a man” (Orgel 151). Macbeth’s attempts to establish a firm sense of his manhood by killing Duncan and anyone else who might bar his way to the throne are destined to self-destruction. Since “nothing is but what is not,” Macbeth abandons his fear of murdering King Duncan (1.3.143). Nevertheless, his mind becomes weaker and his fear grows after killing Duncan because “by defying God’s natural order, Macbeth forfeits his own claim to manhood” (Ribner 157). His manhood does not deserve reward because his blood lust was so extreme. Macbeth is destined to be slain for his bloody violence because “evil inevitably must breed its own destruction” (Ribner 162), and “the wages of ambition always must be death” (Felperin 171). He shows that he knows he will be caught in the cycle of violence he unleashes when he acknowledges “that we but teach/Bloody instructions, which, being taught, return/To plague the inventor” (1.7.7-10). Macbeth recognizes that his acts of bloody violence, though they establish his sense of masculinity, will also destroy him. Banquo is perhaps the only visibly positive male character in the play; he refuses acts of violence to seize his own fate after he hears the prophecy about that his heirs will be kings of Scotland. The Weird Sisters prophesy in act one, scene three that he shall be “lesser than Macbeth, and greater./Not so happy, yet much happier./Thou shalt get kings, Brown 4 though thou be none” (1.3.65-67). Banquo’s admirable qualities, yet his inability to become king, signify how tyrannical actions like those of Macbeth rule the society, gaining all the prestige. Throughout the play, Banquo keeps his “bosom franchised, and allegiance clear” (2.1.28-39), displaying a rare rejection of the blood lust norm in the play that establishes a sense of masculinity for many of the other male characters, including Macbeth, Macduff, Duncan, Malcolm, Siward, Ross, and the other thanes. Standing on the margins of society and looking in to make comments as does a Greek chorus, the three Weird Sisters know the values and desires of the play’s characters, and are able to identify them because these same values of a violent society make them outcasts and persecute them. They identify “high-placed Macbeth[‘s]” corrupted soul, and proclaim, “Something wicked this way comes,” when he approaches (4.1.98, 4.1.45). The Weird Sisters know the characters’ thoughts and vocally reiterate their desires, but the characters’ speech develops of its own accord. When he meets the Weird Sisters, Macbeth “seems rapt withal,” overwhelmed to find his desires appear before him in such an “uncanny guise” as they render their prophecy (1.3.57). They do not pave the path of the characters’ destruction, nor force them to a downfall. Rather, as outsiders who understand the male violence of the culture because they are targets of it themselves, they look in and predict this “tragedy of damnation” (Felperin 157). The Weird Sisters do not suggest that Macbeth murder to Duncan, but can see that a violent ambition poisons him and an ease in committing the most aggressive and bloody killings characterizes the “bravery” that Duncan and the thanes praise in Macbeth. In the “hurly burly” of battle, which the Weird Sisters comment upon in the first scene of the play, Macbeth “unseemed” Macdonwald “from nave to chops” and hung his head on the Brown 5 battlements. The Weird Sisters’ prophecies do not tempt or compel Macbeth to do something he does not desire. Rather, they merely make plausible inferences from their observations of Macbeth’s unbounded violence and aggression—for which he is praised by the King and thanes—and from his obvious longstanding ambition, which he and Lady Macbeth discuss once Macbeth shares with her the prophecy. The Weird Sisters are shrewd readers or interpreters of his character and of the bloody, aggressive, and masculinist culture in the world of the play. The three Weird Sisters never refer to themselves as witches though the males of the play refer to them as such, and they are usually automatically discussed as “the witches” far more often than as the three “Weird Sisters.” A footnote in William C. Carroll’s edition of Macbeth: Texts and Contexts defines the Weird Sisters as women connected with fate or destiny. Associating them with this power is a significant statement on the flaws of Macbeth’s violent nature, which destines him for acts of bloody aggression; blood lust will have tragic consequences. The Weird Sisters are an integral addition to the play, but critics frequently refute their importance. As “witches,” they are scapegoats for this society’s evil wishes and targets of the violence perpetuated by aggressive men. These “imperfect strangers” are made to look like what Helms calls “withered crones” when Banquo says, “What are these/So wither’d and so wild in their attire?/That look not like th’ inhabitants o’th’earth,/And yet are on’t?” (1.3.70, 1.3.39-42). The play suggests their deformity, but witches were also thought to seduce men and be insatiable, in keeping with patriarchal society’s definition of deviance and its fear of powerful women. Furthermore, the Weird Sisters are “the opposite of people who occupy rigid Brown 6 position in the hierarchies of rank and gender” and are easy targets for the blame in eliminating political rivals, as James VI of Scotland used accusations of witchcraft to deal with some of his opponents (Helms 174). The Weird Sisters are on the outside looking in, “telling the truth about the world of the play—that there really are no ethical standards in it, no right and wrong sides” (Orgel 146). Indeed, they “are only capable of seeing what is likely to happen and have no way of defining the course of events” (Dimatteo, par. 1). Some critics even go so far as to suggest that any positive value in the play lies with the three Weird Sisters, for they are “radical separatists, who scorn male power and lay bare the hollow sound and fury at its heart” (Helms 167). The Weird Sisters and Lady Macbeth are shunned and made out to be evil villains because they deviate from the norm. They are women with power, but unlike the men, they do not “use supremacy by the route of violence” (Meyer 90). Shakespeare “locates the source of his culture’s fear of witchcraft” when he presents the women as having “maternal malevolence” (Helms 168). The androgyny of the Weird Sisters correlates to their assumed propensity toward evil, as they have beards, a typically male physical trait. Schiffer points out, “according to popular belief” witches were always bearded, but in reality, they were just different (205). As outcasts, they are able to recognize the corruption and brutality of nobility and predict the downfall of its hubris, yet they have no power to make things occur. Macbeth says, “Were they not forc’d with those that should be ours,/We might have met them direful, beard to beard,/And beat them backward home” (5.5.5-7). This relates to the witches because one use of the word “beard” in Shakespeare’s time was the phrase, “to Brown 7 make (a man’s) beard,” which meant “to outwit or out trick him” (Schiffer 208). Yet the witches do not trick Macbeth, they only show him his future based on their understanding of his violent character and boundless ambitions. The play debunks the belief by some, but not all, commentators in the Renaissance, that women accused of witchcraft possessed supernatural powers. The Three Weird sisters only appear masculine because of their beards, but they do not act in the violent, bloody, and aggressive ways that define masculinity in the world of the play. Nevertheless, the male characters condemn them as deviant females because they do not emulate the culturally accepted norms of femininity. Unlike the Three Weird sisters, Lady Macbeth “wants to become a man, not play at being one” (Schiffer 208). Macbeths’ urging that “false heart must hide what the false heart doth know” (1.7.82-83) conveys how the face that Lady Macbeth puts on “not only hides her evil thoughts and deeds from others, but also conceals her womanhood from her husband and herself” (Schiffer 208). One might say Lady Macbeth has a narrow idea of manhood, but it is the one expressed in her society. Critics often deem Lady Macbeth a manipulator, who persuades Macbeth to murder the king, and who pushes him to do that which he never would have done on his own. But the text makes it clear that she is merely reminding him of his previously stated ambitions and lust for power, which she wholeheartedly shares with him. Lady Macbeth only “give[s] voice to Macbeth’s inner life, [and] release[s] in him the same forbidden desire that the witches have called forth.” She “surely is not the culprit, any more than Eve is—or than the witches are” (Orgel 151). Lady Macbeth has been shaped to believe in the superiority of male traits. Both she and Macbeth “equate femininity with cowardice, fear, weakness, passivity, and Brown 8 vulnerability” (212). Schiffer adequately describes their close-minded attitudes in this statement: for the Macbeths, “to be strong and valorous and quick to act, regardless of the action, is to be manly [; . . .] to be womanly, by their definition, is to be daunted and fearful, powerless and unfulfilled” (207). They despise weakness and see it as feminine, just as the dominant culture elevated masculinity and debased femininity. Consequently, Lady Macbeth aspires to “unsex” herself and become just as aggressive and violent as her husband. While one could argue that her aspiration to unsex herself reveals her deviance, it also throws the culture’s definitions of masculinity into high relief so that we can see them more clearly. Her appropriation of masculinist attitudes and behaviors helps us see them more clearly for what they are: deviant and inhumane in themselves. The ideal of masculinity extolled in the world of the play is itself unnatural and destructive, and it appears most clearly so when it is role-played by a female character, Lady Macbeth. The play’s conclusion suggests the endless cycle of violence and bloodshed in a world in which masculinity is defined by aggression, dominance, and lust for power. No women or children survive the tragic actions of the play. Lady Macbeth kills herself and Lady Macduff is slaughtered along with her children, while her husband Macduff has absented himself to protect Malcolm, Duncan’s successor as King. Male bonding and bloody warfare take precedence over relationships with women and children in the world of the play. Once Macbeth’s ambitions are fulfilled—to his downfall—the three Weird Sisters disappear. As Macduff kills Macbeth and Malcolm is proclaimed King of Scotland, order is apparently restored, but the absence of all female characters suggests that this is a social order that is hostile to domestic life, hostile to women and children. The order restored at the end of the play is one that must sacrifice women and children to Brown 9 ensure the fruition of male ambitions. The destructiveness of masculinity itself, as the world of the play defines it, still exists, yet the culture is blind to it. The need to define one’s masculinity by acts of violence and bloody aggression remains the central test of one’s manhood in this society, as Macduff’s reappearance onstage with Macbeth’s decapitated head suggests. The ending of the play is entirely male-centered and stresses males’ physical and psychological strength in being violent. After all, Macbeth is the one who kills Duncan and all his potential rivals after gaining the throne, not Lady Macbeth. Macbeth’s confidence encourages his bloody tyranny and he “cannot taint with fear” once he allows his own masculine violence to shape his destiny (5.3.3). He will stop at nothing to know glory and lashes out against those who could hinder his succession. Macbeth’s bloody rule makes Inverness into a kind of hell on Earth. As the comic Porter’s scene suggests, Macbeth’s castle is the entrance to Hell where true wickedness reigns. And that wickedness is masculinity itself, as Macbeth and the other characters understand it. The witches dwell outside of this realm, proving they are not evil as are Inverness’s inhabitants. Macbeth’s kingdom is a place where revenge is second nature and “where to do harm/Is often laudable, to do good sometimes/Accounted dangerous folly” (4.2.73-75). Grief is converted to anger and it is best to “blunt not the heart, enrage it” (4.3.230-31). In act three, scene six, Hecate foreshadows the dire consequences awaiting Macbeth’s ambition when she reveals that “thither he/Will come to know his destiny” because “[s]ecurity/Is mortals’ chiefest enemy” (16-17, 32-33). Macbeth is convinced of his need and justification for becoming King. This is evident in his belief that “[he] has Brown 10 bought/Golden opinions from all sorts of people,/Which would be worn now in their newest gloss,/Not cast aside so soon” (1.7.33-36)—that “the strength of [the witches’] illusion/Shall draw him to his confusion” (3.6.28-29) and he will suffer for his crimes by going mad and losing his life. He overextends the norms of masculinity and disregards the fault of his actions. His violent ambition is the poison that kills him, for he has “no spur/To prick the sides of [his] intent, but only/Vaulting ambition, which o’erleaps itself/And falls on th’ other” (1.7.25-28). Shakespeare’s Macbeth comments negatively on cultural norms that define females as deviant in their strength and males as heroic in their violence and blood lust. He suggests that in a society where violence is laudable, there is no place for women and children, family life and domesticity. Further, all men suffer because they are constantly called upon to demonstrate their manhood through acts of aggression and bloodshed, as in the case of Macduff or young Siward. At the opening of the play, Macbeth’s violence demonstrates his manly bravery when he decapitates Macdonwald: “For brave Macbeth—well he deserves that name—/Disdaining Fortune, with his brandished steel,/Which smoked with bloody execution” (1.2.16-18). Macbeth, however, loses all he violently gains as he engages in further acts of bloodshed to prove his masculinity to himself and his wife. Macbeth’s regicide begins his downfall, and he comes to know that “hell is murky” when he must continue killing to wear borrowed robes and to maintain his masculinity in a world of men arrayed against him, who also define their masculinity in terms of violent action (5.1.29). “Blood will have blood,” when a culture’s definition of manhood is grounded in violence, aggression, and bloodshed. Brown 11 Works Cited Carroll, William C. Macbeth: Texts and Contexts. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s. 1999. Dimatteo, Anthony. “‘Antiqui Dicunt’: Classical Aspects of the Witches in Macbeth.” Notes and Queries 41 (1994): 12. par. Online. Felperin, Howard. “A Painted Devil: Macbeth.” Shakespeare Tragedies. Ed. Harold Bloom. New York: Chelsea House, 1985. 157-76. Helms, Lorraine. “The Weyward Sisters” Towards a Feminist Staging of Macbeth.” New Theatre Quarterly 8 (1992): 167-77. Huggett, Richard. Supernatural on Stage. New York: Taplinger, 1975. Meyer, Rosalind S. “‘The Serpent Under ‘T’: Additional Reflections on Macbeth.” Notes and Queries 47 (2000): 86-90. Orgel, Stephen. “Macbeth and the Antic Round.” Shakespeare Survey 52 (1999): 143-53. Brown 12 Ribner, Irving. Patterns in Shakespearian Tragedy. Totowa: Roman and Littlefield, 1960. Smidt, Kristen. “Spirits, Ghosts, and Gods in Shakespeare.” ES 77 (1996): 422-38. Williams, George Walton. “‘Time For Such a Word’: Verbal Echoing in Macbeth.” Shakespeare Survey 47 (1994): 153-59.