making fire mean more than fire. how authors use symbols

advertisement

MAKING FIRE MEAN MORE THAN FIRE. HOW AUTHORS USE SYMBOLS

No work of fiction shows how writers use symbols better than Ray Bradbury's

haunting novel of the future, Fahrenheit 451.

Next year marks the golden anniversary of an original and alarming vision of the

future by an American writer. In 1950, Galaxy Science Fiction magazine published a

stow called "The Fireman," written by 29-year-old Ray Bradbury. In 1953, a longer

version was published as a novel: Fahrenheit 451. Since then, it's been read by tens of

millions.

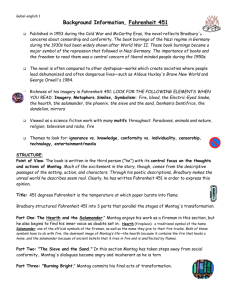

The World of Fahrenheit 451

The future America of Fahrenheit 451 is a bizarre place. Young people engage in

violent games and murderous joyriding. Cars are allowed to travel at terrifying speeds;

one character is arrested, in fact, for driving at only 40 miles per hour. People swallow

overdoses of sleeping pills so often that paramedics go from home to home pumping

stomachs. Walls in homes have been replaced by four-sided wall-TVs, and people take

part in interactive soap operas with "parlor families" that are more real to them than

their own families. Bombers shatter the night, preparing for a war that no one knows

anything about.

In Bradbury's nightmarish vision, creativity and independent thinking have been

outlawed by a shadowy government. It is a crime to own books. The government uses

fire departments to enforce this ban. Firemen do not put out fires; instead, they start

them. When neighbors report that there are books to be found in a home, the firemen

con{e to torch the books and the building, and the police arrest its inhabitants. Guy

Montag, the fireman whose gradual rebellion is revealed in Fahrenheit 451, recites the

firefighters' slogan: "Monday burn Millay, Wednesday Whitman, Friday Faulkner, burn

'em to ashes, then burn the ashes."

What does "Fahrenheit 451" have to do with all this? As the novel’s title page

explains, that is "the temperature at which book-paper catches fire, and burns. ..." The

title reveals the central symbol around which Bradbury organized Fahrenheit 451: fire.

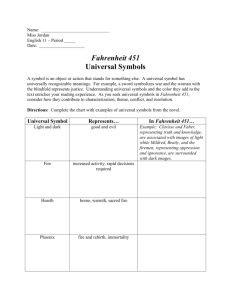

We see symbols every day: from traffic signs, to flags and religious symbols, to a

friend's wave of hello or goodbye, to the newest sneakers or shades (status symbols).

These are real objects or actions, but they have meanings that go beyond their literal

ones. Symbols in stories work the same way. Each time fire appears in Fahrenheit 451, it

is real fire. Its bunting is part of the action of the stow. But it also has larger significance.

Taken together, the fire references point toward Bradbury's theme.

English II – L1

Mr. De Vito, Sr.

-1-

MAKING FIRE MEAN MORE THAN FIRE. HOW AUTHORS USE SYMBOLS

A Pleasure to Burn

Fire appears in the novel's memorable opening passage--a description of a bookburning from Montag's point of view:

It was a pleasure to burn.

It was a special pleasure to see things eaten, to see things blackened and changed.

With the brass nozzle in his fists, with this great python spitting its venomous

kerosene upon the world, the blood pounded in his head, and his hands were the

hands of some amazing conductor playing all the symphonies of blazing and

burning to bring down the tatters and charcoal ruins of history. ... He flicked the

igniter and the house jumped up in a gorging fire that burned the evening sky

red and yellow and black.

This beginning makes readers see how upside-down the society of Fahrenheit 451 is:

Not water, but kerosene, comes from the hoses of these firemen. By using the metaphor

of the conductor, Bradbury explains the "pleasure" of burning: The fireman feels

powerful when he causes things to "change." And what Montag changes is the past

itself: the "charcoal ruins of history."

As children, most of us enjoyed watching a piece of paper, or a log in a fireplace,

burn, fold in on itself, and collapse. Bradbury knows this, and uses this knowledge to

make the description work.

Captain Beatty, the fire chief, sees burning books as a way to make everyone equal:

"Surely you remember the boy in your own school class who was

exceptionally 'bright,' did most of the reciting and answering while the others ...

[hated] him. ... We must all be alike. Each man the image of every other; then all

are happy. ... A book is a loaded gun in the house next door. Burn it. ... Burn all,

burn everything. Fire is bright and fire is clean. ... [Fire] destroys responsibility

and consequences. A problem gets too burdensome, then into the furnace with

it."

Montag knows what he means: "It was good to burn," he thinks, to "snatch, rend, rip

in half with flame, and put away the senseless problem. ... Fire was best for everything!"

But he also begins to see fire in another way. In one scene, a woman refuses to leave her

burning house, preferring to die with her books. Montag cannot forget this. He tells his

wife, Mildred, "This fire'll last me the rest of my life."

English II – L1

Mr. De Vito, Sr.

-2-

MAKING FIRE MEAN MORE THAN FIRE. HOW AUTHORS USE SYMBOLS

A Strange, Warm Fire

If Fire is a symbol of destruction and conflict in Fahrenheit 451, it is also a symbol of

light and peace. In an early scene, Montag is having a conversation with Clarisse, a freespirited teenager who asks troubling questions: "Do you ever read any of the books you

burn?" "Are you happy?" Her frankness and openness bring a memory to his mind:

One time, as a child, in a power failure, his mother had found and lit a last candle

and there had been a brief hour of rediscovery, of such illumination that space lost its

vast dimensions and drew comfortably close around them, and they, mother and son,

alone, transformed, hoping that the power might not come on again too soon.

Compare the language of that passage to the Fast passage quoted on page 15.

Rediscovery, illumination, comfortably, hoping--as opposed to python, venomous,

blazing, and gorging. Bradbury has shifted from violent language to language of peace.

The transformation of Montag--and of fire--has begun.

In fact, we later learn that Montag's rebellion had already begun: He had been

hoarding confiscated books for months. But the conversation with Clarisse and the

childhood memory increases its pace. Montag quarrels with Mildred. He calls in sick.

He reads his cache of books. He seeks out Faber, a retired professor and secret booklover, and they hatch a wild plot to sabotage the firehouses. He reads poetry to his

wife's appalled friends. He is reported and arrested. His books and house are burned.

He escapes and becomes a fugitive, closely pursued by the police and the fearsome

Mechanical Hound. He flees to the wilderness. There, he comes upon--a fire:

He stopped, afraid he might blow the fire out with a single breath. ... He stood

looking at it from cover. That small motion, the white and red color, a strange

fire because it meant a different thing to him.

It was not burning, it was warming.

He saw many hands held to its warmth. ... Above the hands, motionless faces ...

flickered with firelight. He hadn't known fire could look this way. He had never

thought in his life that it could give as well as take. ... He stood a long long time,

listening to the warm crackle of the flames.

Around the campfire is a group of men who are working to keep knowledge alive,

not by hoarding books but by memorizing them, so that the contents can be passed

from generation to generation. They don't have books; in a very real way, they are

books--or walking libraries. And, Montag discovers, they are part of a nationwide

English II – L1

Mr. De Vito, Sr.

-3-

MAKING FIRE MEAN MORE THAN FIRE. HOW AUTHORS USE SYMBOLS

network of people who, flying beneath the radar of the government, do the same thing.

As the city goes up in the flames of war behind him, Montag joins this group.

Symbols and Themes

Fahrenheit 451 raises challenging questions. Is it better to be unthinking and content,

or thoughtful and troubled? Can people really be happy if they are passive automatons?

But do books--or, rather, the ideas in them, or the act of pondering those ideas--assure

happiness and wisdom? Doesn't history suggest otherwise?

There are no easy answers. But Ray Bradbury clearly is on the side of the books.

Granger, one of the book people Montag joins at the end of Fahrenheit 451, probably is

speaking for the author when he decodes the symbol of fire one more time, by retelling

the legend of the mythological bird, the Phoenix:

Every few hundred years he built a pyre and burned himself up. ... But every time

he burnt himself up he sprang out of the ashes, he got himself born all over again. And

it looks like we're doing the same thing, over and over, but we've got one thing the

Phoenix never had. ... We know all the silly things we've done for a thousand years and

as long as we know that and always have it around where we can see it, some day we'll

stop making the funeral pyres and jumping in the middle of them. We pick up a few

more people that remember, every generation.

Lenhoff, Alan. “Making fire mean more than fire. How authors use symbols”. Writing. Oct99, Vol. 22 Issue 2, p14, 3p.

12-May-2010. <http://web.ebscohost.com.prxy2.ursus.maine.edu/ehost/detail?vid=4&hid=113&sid=164f73092df2-48dd-adc3-ae087c5bcdac%40sessionmgr114&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#db=

f5h&AN=2716163>.

English II – L1

Mr. De Vito, Sr.

-4-