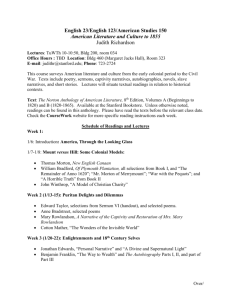

Lecture 2: The Legacy of Puritanism 2

advertisement

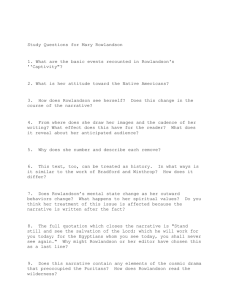

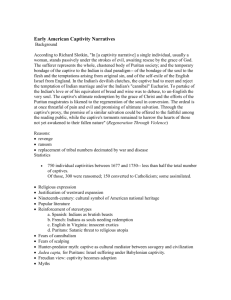

Lecture 3: The Legacy of Puritanism / 2 Critical reading Nellie McKay: “Autobiography and the Early Novel.” The Columbia History of the American Novel. 26-45. Lowance I, Mason: “Biography and Autobiography.” CLHUS. 67-82. Alan Heimert: “Jonathan Edwards, Charles Chauncy, and the Great Awakening.” CLHUS. 113.126. A) The “Jeremiad” - crises of New England theocracy (secularization: doctrinal controversies; religious uncertainties among the young; failures in conversion; immigration; shortage of land; Indian wars) - the “jeremiad”: blueprint for Puritan discourse; following the logic of the (Old Testament) Books of Jeremiah and Isaiah (recalling past piety and greatness, lamenting present sins, call for a return to original conduct) Election sermons May: election of magistrates for General Court (1st: Boston 1634; printed beginning with 1667) 1. biblical passage + “Explication”; 2. “Doctrine”; 3. “Application” integrating the theory of Puritan society and the current social and religious practices e.g. Increase Mather: The Day of Trouble is Near, 1674 B) The Captivity narrative 2: Puritan spiritual autobiographies 1682 Mary Rowlandson: The Soveraignty (sic) and Goodness of God 1707 Rev. John Williams of Deerfield: The Redeemed Captive, Returning unto Zion early autobiographies: main focus on the religious dimensions of the captivity experience - later: vehicles for promulgating white hatred of Native Americans; argument for Indian removal - initiation journey from Death to Rebirth; movement from ignorance to knowledge - pattern: Separation from her culture > Transformation > Return (= symbolic death) (ordeals: movement from ignorance to knowledge) (spiritual rebirth) Mary Rowlandson: The Sovereignty and Goodness of God, Together with the Faithfulness of His Promises Displayed; Being a Narrative of the Captivity and Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson, Commended by her to all that Desire to Know the Lord’s Doings to, and Dealings with Her. Especially to her Dear Children and Relations (written in 1677, published in 1682, with Increase Mather’s preface) - 11 weeks (10 Feb, 1676 during King Philip’s War > until May 2, 1676) in the captivity of Narragansett Indians - immediately after returning: 1676 A True History of the Captivity and Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson, published in 1682 with the title The Sovereignty and Goodness of God - account: intimate rather than abstract and theological; the human perspective on the captivity experience - immersion in a Native American culture foreign to his own (a mixture of Puritan religious perspective and anthropological investigation: a theological account of providence acting in specific human events and immersion into the culture of Native Americans) - intended to instruct rather than exploit the stereotype of the savage Indian - the account of her “removes”: trial and deliverance interior journey (the actual experience: a 150-mile journey with the Narragansetts) - symbolic landscape rather than literal one: the darkness of the forest and the soul when God turns his face away - Indians depicted as “murtherous captors,” “merciless heathen,” “a company of hellhounds” - as a faithful Puritan, she transcends that symbolic death by finding meaning in her afflictions: recreates herself; seeks to discover what failings led to her punishment her duty in captivity: to concentrate on submitting to God’s will learns how to provide for herself the voice of a Christian in the wilderness crying out to God One principall ground of my setting forth these lines is to declare the Works of the Lord, and his wonderful power in carrying us along, preserving us in the Wilderness, while under the Enemies hand, and in returning us into safety again. - her release: assures her of having gained redemption (promise of salvation) - reveals more about the strength of Puritan culture than about the true characteristics of Mary Rowlandson - tells her story publicly (the lesson from such ordeals passed on to others for moral instruction) - God used her for His purpose: to convey the spiritual meaning of her existence to others the “jeremiad” design of the narrative (jeremiad: call for a return to a former state of innocence and moral strength that has been lost) The next day was the Sabbath: I then remembered how careless I had been of God's holy time; how many Sabbaths I had lost and mispent; and how evilly I had walked in God's sight; which lay so close upon my Spirit, that it was easie for me to see how righteous it was with God to cut off the thread of my life, and cast me out of his presence for ever. Yet the Lord still shewed mercy to me, and upheld me; and as he wounded me with one hand, so he healed me with the other. 1. victim reflecting upon the period of life preceding the capture; discovering personal faults deserving God’s punishment 2. repentant victim searching within herself; making a vow to return to earlier piety I then remembered how careless I had been of God’s holy time, how many Sabbaths I had lost and misspent, and how evilly I had walked in God’s sight. 3. freedom as reward for repentance; sign of divine providence and election How righteous it was with God to cut off the thread of my life and cast me out of His presence forever. Yet the Lord still showed mercy to me; and as He wounded me with one hand, so He healed me with the other. - transforms her suffering into a sign of God’s goodness - the captivity period: provided the opportunity to prepare her heart for grace: to search out the corruption in her nature and rediscover the glory of God in His scriptures Increase Mather’s Preface: the official Puritan interpretation of Mary’s ordeal and her narrative - people in New England (and leaders in England) should understand the reasons and meaning of the catastrophe (King Philip’s War ) in providential terms the woman’s text I cannot but take notice how, at another time, I could not bear to be in the room where any dead person was; but now the case is changed; I must and could lye down by my dead Babe, side by side, all the night after. I have thought since of the wonderful goodness of God to me, in preserving so in the use of my reason and senses in that distressed time, that I did not use wicked and violent means to end my own miserable life. - Mather’s “Preface” // Mary Rowlandson’s narrative // the Rev. John Rowlandson’s sermonic afterword - beneath the standard religious rhetoric: personal experience of grief and loss - accounts of interactions and experience with Native Americans (although in the language of racial stereotypes) - still: individualizes Indians as she gives account of customs / civilities / her interactions with them C) Revivalism and the Conversion Narrative Yale College (founded by the conservative clergy in 1701) vs. Harvard The Great Awakening - from the 1740s: a wave of religious awakenings and conversions under the influence of itinerant clergy “New Lights” or “New Side” clergy (educated at Harvard) vs. “Old lights,” “Old Siders” (Yale College) Jonathan Edwards: Personal Narrative, published posthumously, in The Life and Character of the Late Reverend Mr. Jonathan Edwards, 1765 description of his own conversion experience structured like earlier conversion accounts: 1. pious religiosity as a child; 2. doubts in youth; taken to sin; 3. illness; recovery and the experience of conversion; 4. falling back to sin; 5. the moment of conversion as a mystical experience invokes natural imagery in order to blend the worldly and the divine the moment of conversion: in nature infused with elements of the supernatural; the divine beauty of nature the ecstasy of conversion and “new life” D) Persisting metaphors in American culture - the utopian concept of America: the “City upon a Hill,” the New Jerusalem; - the sense of mission: for the justification of American imperialism, “Manifest Destiny” (the 1840s)