History 351, Syl F97 - University of Puget Sound

advertisement

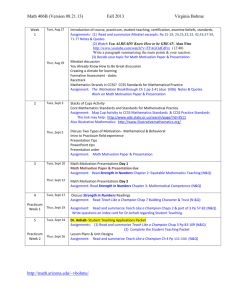

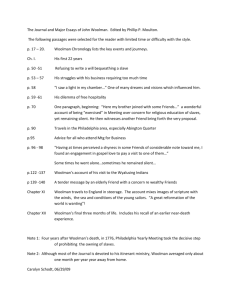

History 351 EARLY AMERICAN BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY Spring 2007, TTh 12:30 to 1:50, Wyatt 308 William Breitenbach Office Phone: 879-3167 E-mail: wbreitenbach@ups.edu Web: http://www.ups.edu/x6705.xml Office: Wyatt 141 Office Hours: MTWThF 11 to 12 and by appointment This course will examine the life stories of people in British North America during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. In addition to several biographies, we’ll read personal narratives by early Americans written in a wide variety of narrative forms: autobiographies and memoirs, secret diaries, diaries intended for publication, journals of spiritual self-examination, picaresque adventure tales, captivity narratives, missionary reports, stories of witchcraft and demonic possession, reminiscences of warfare, and records of travel and exploration. Our narrators will be as diverse as their genres. We’ll hear from men and women, both famous and obscure, rich and poor, young and old. We’ll encounter Indians, blacks, and whites; immigrants and the native-born; free men and women as well as slaves, indentured servants, and children bound to service. The authors will include government officials, tobacco planters, merchants, artisans, ministers, scientists, students, schoolteachers, hunters, warriors, explorers, housewives, and ordinary farmers. Some were Puritans, Anglicans, Quakers, Moravians, or Deists; still others were called “heathens”; and a few of them seem to have been untroubled by any religious beliefs whatsoever. They came from Europe, Africa, and America; they settled in New England, the Middle Colonies, the South, and the backcountry. They resided in bustling seaport cities, on huge plantations, in rural villages, and isolated farms. Some of them, without fixed abode, roamed the highways, the seas, or the wilderness. By listening attentively to what these individuals have to tell us, we’ll learn a lot about early American history. Here are some of the themes that their stories can illuminate: (1) the deep involvement of colonists in a transnational Atlantic world that circulated peoples and goods and cultures among four continents; (2) the interactions of Europeans, Native Americans, and Africans with one another, and especially the acculturation that occurred as a result of these interactions; (3) the tension between tradition and innovation in the responses of all three of these groups to “new world” circumstances; (4) the prevalence and the significance of brutal violence and lavish bloodshed in early American life; (5) the fluidity, mutability, and insecurity of life in America, where sudden conversions, inversions, and reversals of fortune were common in both spiritual and secular affairs; (6) the problem of transmitting and maintaining traditional forms and institutions of social order and social authority in America; (7) the problem of securing and controlling dependents, especially bound laborers, the solutions devised to that problem, and the strategies by which the dependents sought to rise to a condition of independence; (8) the role of religion, both as public institution and as private experience, in shaping people’s comprehension of their experience in America; (9) the competing and shifting definitions of success and “the good life”; (10) the ways in which the American landscape, with its astonishing natural abundance, transformed colonists’ cultural values and social institutions; (11) the complex and conflicted interactions between a creolized, provincial American society and a metropolitan British society, which served as imperial protector, political threat, and cultural model; and (12) the relationship between the formation of distinctive regional identities and the emergence of a common American way of life. History 351 Spring 2007 A useful way to investigate these themes is to think of early America as a place of borderland encounters. The theme of borders, frontiers, margins, marchlands, and peripheries runs through our readings. We’ll see early Americans confronting, erecting, defending, and crossing innumerable boundaries. Some of these are the physical ones between America and Europe or Africa, and between coastal settlements and wilderness interior. Other borders are cultural and social—places and processes where racial, ethnic, religious, gender, class, and generational groups were delineated and ordered. If borders of these kinds seem familiar to us today, there are others that we can view only as alien and vanished frontiers: the border between the natural and supernatural realms, or the border between the medieval and modern worlds. As I’ve compiled the reading list for our course, I’ve been struck by the volume and variety of encounters, both willing and unwilling, across such borders. These liminal experiences provoked diverse responses: conversions and apostasies, raids and retreats, trespasses and removals, acculturations and revitalizations, renunciations and creolizations. The biographies and autobiographies that we’ll be reading during the coming semester will give us an immediate and concrete sense of what it must have been like to live on the margins. Our ultimate aim will be to determine if, out of all these borderland encounters, a distinctive and common American culture had developed by the eve of the Revolution. Course objectives. The course has four pedagogical objectives: To give you a general knowledge of American history before the Revolution To help you recognize the tremendous diversity of cultures and experiences in 17th- and 18th-century America, and especially to help you understand how American culture and national identity emerged out of the historical encounters of diverse peoples—European, African, and Native American—in an Atlantic world. To advance your methodological sophistication by giving you experience in reading and analyzing different types of biographical and autobiographical sources and materials. To help you recognize that personal identity is a historical phenomenon—i.e., that the ways personal identity was constructed and experienced in the past differ from the ways that we construct and experience our personal identity today. BOOKS The following required books are for sale at the University Bookstore. Other editions are okay. Camilla Townsend, Pocahontas and the Powhatan Dilemma (Hill and Wang) Edmund S. Morgan, The Puritan Dilemma: The Story of John Winthrop, 3rd ed. (Pearson) William Moraley, The Infortunate: The Voyage and Adventures of William Moraley, an Indentured Servant, ed. Susan E. Klepp and Billy G. Smith, 2nd ed. (Penn State Press) James E. Seaver, A Narrative of the Life of Mrs. Mary Jemison, ed. June Namias (Oklahoma) Olaudah Equiano, The Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African (Dover) John Woolman, The Journal of John Woolman, and A Plea for the Poor, ed. Frederick B. Tolles (Citadel) Benjamin Franklin, The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin (Dover) Blackboard Website Readings listed in the syllabus with “[Bb]” may be found online at the Blackboard website for History 351 (course ID: Hist351aSp07): http://blackboard.ups.edu/. I’ll also put the syllabus and writing assignments on Blackboard. If you have not previously used Blackboard, you can find FAQs and instructions for creating an account at http://projects.ups.edu/blackboard/. The password allowing access to the course site will be provided in class. 2 History 351 Spring 2007 PROCEDURES, REQUIREMENTS, AND EXPECTATIONS Class participation This will be a discussion class. Discussions work well if everyone comes to every class on time with the reading assignment completed, with some ideas to talk about, and with the books in hand to refer to when talking about those ideas. By contrast, discussions sputter if some people—and it doesn’t have to be too many—are repeatedly absent, late, unprepared, bookless, sleepy, inattentive, uncommunicative, dismissive, or defensive. Come to class ready to talk. Put your ideas out there for others to endorse, challenge, and transform. Be willing to ask a question, confess confusion, disagree with friends, make a claim, take a stand, and change your mind. In this course, it is better to say something rash, foolish, or wrong than to say nothing at all. Your consistent, thoughtful, informed participation will be important in determining both the success of the course and the grade that you receive in it. After every class, I’ll evaluate your contribution to other students’ learning. Students who are not in class will receive a 0. Students who attend but do not participate significantly will receive a 2. Those who participate significantly will receive a 3, and those whose participation is outstanding will get a 4. You can think of twos as roughly equivalent to C’s, threes as B’s, and fours as A’s. At the end of the semester, I’ll total the points and give you a participation grade, which will count for 25% of the course grade. At my discretion, the course grade may be adjusted upward for students who have made an extraordinary contribution to the class or downward for those with poor attendance or inadequate participation. Policy on Absences. I expect you to attend all class meetings unless you have arranged an excused absence. Let me know in advance if you must miss class because of a universitysponsored activity. Notify me by email or voice mail if you miss class because of an illness or emergency. Tell me before class if possible. (See below for instructions about response papers.) If your absences become excessive, I may ask the Registrar to drop you from the course. Response papers The class will be divided into a Tuesday Group and a Thursday Group. Excluding the first two classes and the day of the midterm examination, each group has thirteen class meetings. On days when your group is on duty, you are to bring to class a brief response paper in which you pose and answer a question about the reading assignment. The main purpose of response papers is to improve our discussions. Response papers will be the only papers assigned in this course. Each response paper should identify an interpretive problem or puzzle raised by the day’s reading, state it in the form of a question, and then go on to propose, discuss, and defend a possible answer to this question. By a problem or puzzle, I mean the sort of debatable question might be used to initiate a class discussion or that might be asked on an essay exam. The question can be provocative; it must be disputable. In other words, the question should permit alternative responses by informed respondents. Or, put still another way, if you pose a good question, it should be possible for someone else in the class to disagree with your answer. For historians, the best questions begin with why or how. Particularly good questions are ones that connect the day’s reading to readings from prior classes. But whether you link together many texts or focus on just one rich passage from the day’s reading assignment, make sure that you come up with a problem that is worth solving; that is, a problem for which the solution has important historical consequences or implications for our understanding of the course’s subject. The body of the response paper should be a sustained argument that answers your question. In making your case, you will need to support your claims by analyzing particular passages in the readings. You will need to spell out the reasoning behind your assertions. And finally, you will need to answer the “So what?” question by explaining the implications and larger significance of your interpretation. See how far you can push your ideas. Be bold! 3 History 351 Spring 2007 As you can see, response papers are not just reading notes. They need to do more than just summarize or paraphrase the readings. They should focus on one question, which should be written in bold type at the top of the page. The writing can be informal, but sentences must be grammatical and paragraphs coherent. You do not need to provide footnotes if you quote, but do give parenthetical page-references. Response papers should be typed, double-spaced, and 1½ to 2 pages long (approximately 500 words). Response papers are due at the beginning of class. (Make a second copy if you want to have one in front of you during class.) Because we need the response papers for our class discussions, they will be docked one-third of their point value if they are turned in after class on the same day. Response papers will not be accepted after the day they are due. You may skip up to three of the thirteen response papers without penalty. If you do not use all of your allowed skips, I will drop your lowest response paper grade for each unused skip. Thus, everyone will be evaluated based on the ten best response-paper grades. Important: If you are going to be absent on a day that you have a response paper due, you may submit it to me by email, but it must be received by me before the beginning of class on that day or it will be penalized as late. If you are going to miss class and would prefer to submit a substitute response paper at a later date, you must notify me before class to make arrangements to do so; otherwise it will count as one of your skips. Graded work (The percentage indicates the weight of the assignment in the course grade.) Midterm examination on Tuesday, February 27 (20%) Final examination on Thursday, May 10, from 12:00 to 2:00 (25%) Response papers (your best ten) (30%) Class participation (25%) Grading scale There are 1,000 possible points in this course. Grade levels are A (930-1000), A- (900-929), B+ (870-899), B (830-869), B- (800-829), C+ (770-799), C (730-769), C- (700-729), D+ (670699), D (630-669), D- (600-629), and F (below 600). Other policies Students who do not complete all major writing assignments will receive an F for the course. No written work will be accepted after 5:00 p.m. on Friday of finals week. Normally I do not grant extensions or “Incomplete” grades except for weighty reasons like a family emergency or a serious illness. To request an exception for these or other reasons, notify me before the deadline if possible. As appropriate, provide documentation supporting your request from a doctor; the Counseling, Health, and Wellness Services; the Academic Advising Office; or the Dean of Students Office. Students who want to withdraw from the course should read the rules governing withdrawal grades, which can be found at http://www.ups.edu/dean/Handbook/Grades.html. Students who abandon the course without officially withdrawing will receive a WF. Students who cheat or plagiarize, help others cheat or plagiarize, steal or mark library materials, or otherwise violate the University’s standards of academic honesty will receive an F for the course. Before submitting your first paper, read the discussion of academic honesty in the Academic Handbook at http://www.ups.edu/dean/Handbook/Honesty.html. Ignorance of the concept or consequences of plagiarism will not be accepted as an excuse. In matters not covered by this syllabus, I follow the policies set down in the Academic Handbook, which is available online at http://www.ups.edu/dean/Handbook/toc.htm. 4 History 351 Spring 2007 CLASS SCHEDULE All reading assignments and prep sheets are to be completed before class on the day for which they are listed. Bring this syllabus to class along with the books assigned for the day. 1. Tues., Jan. 16 Introduction to the course Video in class: Black Robe, dir. Bruce Beresford (1992, 101 mins.), excerpts 2. Thur., Jan. 18 John M. Murrin, “Beneficiaries of Catastrophe: The English Colonies in America,” 1-21 [Bb] Greg Dening, “Introduction: In Search of a Metaphor,” in Through a Glass Darkly: Reflections on Personal Identity in Early America, ed. Ronald Hoffman, Mechal Sobel, and Fredrika J. Teute, 1-2 [Bb] Mechal Sobel, “The Revolution in Selves: Black and White Inner Aliens,” in Through a Glass Darkly, 163-76 [Bb] Richard White, “‘Although I Am Dead, I Am Not Entirely Dead’: Constructing Self and Persons on the Middle Ground of Early America,” in Through a Glass, 404-13 [Bb] 3. Tues., Jan. 23: Camilla Townsend, Pocahontas and the Powhatan Dilemma, xi-96 4. Thur., Jan. 25: Townsend, Pocahontas and the Powhatan Dilemma, 96-178 5. Tues., Jan. 30: Edmund S. Morgan, “The First American Boom: Virginia 1618 to 1630,” William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd ser., 28 (Apr. 1971): 169-98 [Bb] Choose one of the following: John Ruston Pagan, Anne Orthwood’s Bastard: Sex and Law in Early Virginia, 11-24 (Anne Orthwood); 27-37 (William Kendall); and 84-90 (Anne’s death) [Bb]; OR T. H. Breen and Stephen Innes, “Myne Owne Ground”: Race and Freedom on Virginia’s Eastern Shore, 1640-1676, pages xv-xxi (Preface); 3-6 (Introduction); 7-18 (Patriarch); 32-35 (Race Relations); and 110-14 (Conclusion) [Bb] 6. Thur., Feb. 1: Morgan, The Puritan Dilemma, ix-92 (through chap. 7, “A Due Form of Government”) John Winthrop, “A Model of Christian Charity” (1630) [Bb] 7. Tues., Feb. 6: Morgan, The Puritan Dilemma, 93-191 (chap. 8, “Leniency Rebuked,” to the end) John Winthrop, “Speech to the General Court” (1645) [Bb] 8. Thur., Feb. 8: John Dane, “A Declaration of Remarkable Providences in the Course of My Life” (1670s), in Remarkable Providences, 1600-1760, ed. John Demos [Bb] Mary Rowlandson, The Sovereignty and Goodness of God, Together with the Faithfulness of His Promises Displayed; Being a Narrative of the Captivity and Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson (1682), read through “The Sixth Remove” [Bb] 5 History 351 Spring 2007 9. Tues., Feb. 13: Rowlandson, The Sovereignty and Goodness of God (finish the book) [Bb] 10. Thur., Feb. 15: Choose one of the three witchcraft cases: John Godfrey: “One Man’s Many Accusers (1658-1669),” in David D. Hall, ed., Witch-Hunting in Seventeenth-Century New England, 115-33 [Bb] John Demos, “John Godfrey and His Neighbors: Witchcraft and the Social Web in Colonial Massachusetts,” William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd ser., 33 (Apr. 1976): 242-62 [Bb] Elizabeth Knapp: “A Servant ‘Possessed’ (1671-1672),” in David D. Hall, ed., Witch-Hunting in Seventeenth-Century New England, 197-212 [Bb], AND EITHER Carol F. Karlsen, The Devil in the Shape of a Woman, chap. 7, pp. 222-51 [Bb] OR John Putnam Demos, Entertaining Satan, chap. 4, pp. 97-131 [Bb] Mercy Short: Cotton Mather, “A Brand Pluck’d Out of the Burning” (1693) [Bb] Mary Beth Norton, In the Devil’s Snare, 176-82 [Bb] 11. Tues., Feb. 20: Donna Merwick, “The Suicide of a Notary: Language, Personal Identity, and Conquest in Colonial New York,” in Through a Glass Darkly, 122-53 [Bb] 12. Thur., Feb. 22: William Byrd II, Secret Diary of William Byrd of Westover, 1709-1712 [Bb] 13. Tues., Feb. 27: MIDTERM EXAMINATION Bernard Bailyn, “A Domesday Book for the Periphery,” in The Peopling of British North America: An Introduction, 89-131 [Bb] T. H. Breen, “Creative Adaptations: Peoples and Cultures,” in Colonial British America: Essays in the New History of the Early Modern Era, ed. Jack P. Greene and J. R. Pole, 195-232 [Bb] Michael Zuckerman, “Identity in British America: Unease in Eden,” in Colonial Identity in the Atlantic World, 1500-1800, ed. Nicholas Canny and Anthony Pagden, 115-57 14. Thur., Mar. 1: William Moraley, The Infortunate (1743), read the prefaces, introduction, and chaps. 1-5 (pp. xi-50 in 2nd ed.; pp. xi-86 in 1st ed.) 15. Tues., Mar. 6: Moraley, The Infortunate, finish the book but skip the appendixes (pp. 51-117 in 2nd ed.; pp. 86-143 in 1st ed.) 16. Thur., Mar. 8: Elizabeth Ashbridge, Some Account of the Fore-Part of the Life of Elizabeth Ashbridge (late 1740s) [Bb] Katherine M. Faull, ed. and trans., “Memoirs of Anne Marie Worbass” (1722-95) [Bb] SPRING BREAK: MARCH 12-16 6 History 351 Spring 2007 17. Tues., Mar. 20: Gottlieb Mittelberger, Journey to Pennsylvania (1756) [Bb] 18. Thur., Mar. 22: James E. Seaver, A Narrative of the Life of Mrs. Mary Jemison (1824), 3-6, 13-33, 55-95 19. Tues., Mar. 27: Seaver, Narrative of the Life of Mrs. Mary Jemison, 96-160 20. Thur., Mar. 29: James H. Merrell, “‘The Cast of His Countenance’: Reading Andrew Montour,” in Through a Glass Darkly, 13-39 [Bb] John Filson, The Adventures of Col. Daniel Boon (1784) [Bb] 21. Tues., Apr. 3: Olaudah Equiano, The Life of Olaudah Equiano (1789), iii-96 22. Thur., Apr. 5: Equiano, Life of Olaudah Equiano, 97-184 23. Tues., Apr. 10: Philip Vickers Fithian, “Journal in Virginia” (1773-74) [Bb] Rhys Isaac, The Transformation of Virginia, 1740-1790, 70-87, 118-20, 131-38 [Bb] 24. Thur., Apr. 12: John Woolman, The Journal of John Woolman and A Plea for the Poor (1774), v-88 25. Tues., Apr. 17: Woolman, Journal, 89-186 26. Thur., Apr. 19 Woolman, Journal, 187-249 T. H. Breen, “An Empire of Goods: The Anglicization of Colonial America, 1690-1776,” The Journal of British Studies, 25 (Oct. 1986): read only 485-96 [Bb] 27. Tues., Apr. 24: Benjamin Franklin, Autobiography (1771-88), iii-72 (Parts One and Two) 28. Thur., Apr. 26: Benjamin Franklin, Autobiography, 73-136 (Parts Three and Four) 29. Tues., May 1: Benjamin Franklin, “Information to Those Who Would Remove to America” (1782) [Bb] Hector St. Jean de Crèvecoeur, “What Is an American?” (1782) [Bb] Michael Warner, “What’s Colonial about Colonial America?” in Possible Pasts: Becoming Colonial in Early America, ed. Robert Blair St. George, 49-70 [Bb] Final Exam: Thursday, May 10, from 12:00 to 2:00 in our regular classroom. 7