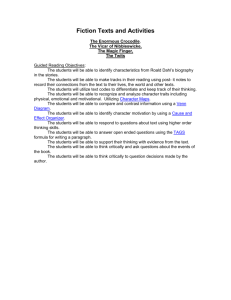

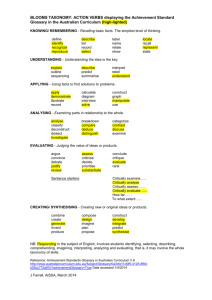

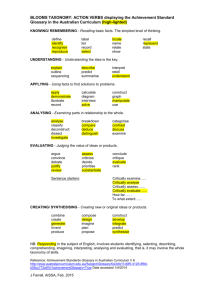

challenging students to think

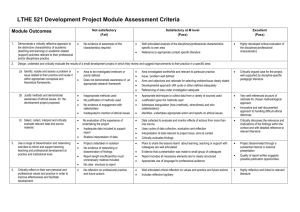

advertisement