Read the entire “Food Desert” Essay Here

advertisement

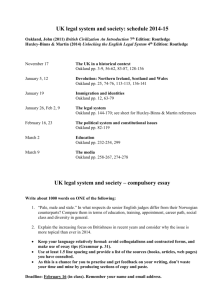

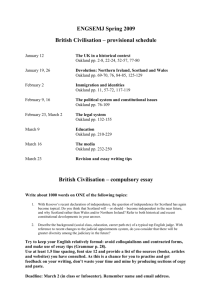

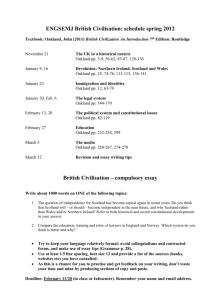

Molly Travis ENVS 147 Szasz Research Paper Deserts in an Oasis Issues of hunger and malnutrition are commonly associated with developing nations and are often overlooked in wealthy countries. However, there is growing areas forming across the United States called food deserts. Food deserts, defined by the Center for Disease Control (CDC), are areas “that lack access to affordable fruits, vegetables, whole grains, low-fat milk, and other foods that make up the full range of a healthy diet”. The causes and impacts of food deserts are based on racial, health, economic, and environmental factors that influence one another. In response to this issue, there is both local and federal action being taken to find a solution. Ultimately, the issue of food deserts and its related problems underlies the greater problem of food security. Food deserts are made up of many qualifiers, but the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) identifies two important guidelines: “A census tract that meets both low-income and low-access criteria including: 1. Poverty rate is greater than or equal to 20 percent OR median family income does not exceed 80 percent median family income 2. At least 500 people or 33 percent of the population more than 1 mile (urban) or 10 miles (rural) from the nearest supermarket or large grocery store.” Food deserts are a dynamic problem influenced by demographic, economic, and transportation shifts within urban and rural areas, and vary depending on the infrastructure of the location. According to the Huffington Post’s article on California food deserts, “nearly 13.5 million people - 46 percent of whom are classified as low-income - live in food deserts nationwide” in addition to the almost 1 million Californian’s who live in food deserts. 2 Although food deserts are found throughout California, a large number of them reside within the Bay Area. In 2009, associates from the University of California at Berkeley released a study that mapped the type of store and availability of nutritious food within Northern California and the Bay Area. Their findings showed that 54 percent of the surveyed stores were convenience stores, and only 19 percent small and 5 percent large grocery stores. What differentiates California from other states is the abundance of major urban cities incorporated into outlying suburbs within the Bay Area. This area of land includes cities like San Francisco, San Jose, Berkeley, and in particular, Oakland in regards to food desertification. These large urban centers are places of minority race and ethnic communities that are often lower income areas. It is important to look at race/ethnicity and income when studying the cause and effects of food deserts. In a comparison of the 2010 Census Records of Contra Costa County and Oakland, California, there is an extreme disparity in racial demographics and the median income. In the greater Contra Costa Country, the population comprised of 9.3% Black, 24.4% Hispanic, 14.4% Asian, and 58.6% white demographics with a median income of $73,721. In the city of Oakland, the population comprised of 28.0% Black, 25.4% Hispanic, 16.8% Asian, and 34.5% white demographics with a median income of $49,190. There is a higher proportion of racial minorities and a lower income in Oakland compared to the rest of the county, which would explain why Oakland is a site of major food desertification. However, the cause for racial and income imbalance across the county is because of the earlier “white flight” migration to the suburbs and the recent gentrification of the city proper. In the article “Oakland is For Burning? Beyond a Critique of Gentrification” by activist bloggers Bay of Rage, the history of mass 3 migration of Southern Blacks to Oakland and the dispersal of whites to the suburbs began the concentration of Blacks and other minorities in urban cities. Furthermore, the current gentrification of Oakland is creating more racial pressure on minorities because “historically black neighborhoods are whitening and rental prices are pushing out the working class elements.” Affordable housing is relocated to the inner city and poverty pockets that suffer the most severely from food deserts. In a paper outlining the impact of food deserts in Chicago, ties are created from health, race, and income disparities. The main indicator of disparities is the Food Balance Effect, which states, “Nutritional challenges … worsen when the food desert has high concentrations of nearby fast food alternatives”. As seen in the Chicago study, the majority of food deserts were predominantly Black communities, and as such suffer the worst of the health effects including increased rates of obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic illness, and premature deaths related to nutritional obstacles. This research can also be illustrated through personal research conducted by myself to study the health effects of food desertification. In order to experience a food system within a desert, I restricted my groceries to a 7-11 convenience store that was walking, bussing, and biking distance, about a mile away from my house. My total spent on a week of food was about $80. Produce was limited to juice, two apples, a fresh vegetable carton, and a fresh fruit carton. The nutritional effects were shocking. My average weekly calorie consumption was 1470 calories a day and the ratio of carbohydrates, fats, and proteins was 60%, 21%, and 19% of my diet, respectively. My diet consisted mainly of starchy, processed foods that resulted in fatigue, irritability, rapid weight loss, and persistent hunger caused by lack of nutritional food. 4 Additionally, economic impacts were found from the 7-11 food desert simulation. My average amount of money spent on groceries was $80 a week, or $4,160 a year. The national median amount of money spent on groceries was $125 a week, or $6,500 a year. Derived from the 2010 National Census, this figure is roughly 11.6% of the average income made by an American family. In Oakland, 11.6% of the average income would be $5,700 spent a year on groceries. If the average amount of money I spent were applied to the demographic statistics of Oakland, for an average family size of 3.27 persons, the yearly cost of groceries would be $13,600. This would translate to 27.65% of my yearly income being spent on groceries compared to the national average of 11.6%. Also, this would be more than double the national average amount of money spent yearly on groceries in the United States. The reason the total is large is because of the dietary choices I made at 7-11. Making smart and nutritional choices costs more money and gets you less food. There are also environmental effects of food deserts. The word “desert” even has environmental connotations, with synonyms like bare, empty, and uninhabitable. If food systems and food deserts were looked at from an ecological perspective, one would see the networking and connection between demographics, locations, availability of food resources, and competition. In an article published by the National Press Association, Steven Cummins applies an eco-geospatial lens to food deserts “given that space, place, and distance are features that may affect the food environment and thus become determinants of diet and health”. The urban planning and development in conjunction with zoning laws shape the landscape of city food systems into environments that are unhealthy and unsustainable. Food deserts are a public issue that is recognized by the federal government and the 5 communities that are afflicted by them. The Bay Area community has responded with activism and support of solving the multitude of problems resulting from food desertification. Oakland Local, a third party news source, published a map of the Oakland Food System including community gardens, food banks, and farmer’s markets to help educate the general population find sustainable, local, and affordable produce and food. Bay area residents have also created new centers of education, sustainable and local food, and outreach by opening People’s Grocery, a non-profit spearheaded by activist Brahm Ahmadi. This is the only grocery store in the neighborhood and would directly connect people with their food and community. There is also a movement outside of grassroots activism through policy change and legislation. The Oakland Food Policy Council (OFPC) works with the City of Oakland by making recommendations on actions that benefit sustainable food systems. The Council is working towards connecting the economic, social, health, and environmental benefits to the community of Oakland through organization, research and outreach of food policies. In 2011, AB 581, the California Healthy Food Financing Initiative (CHFFI) was passed that would ”help bring healthy food retail to underserved communities and more effectively target programs and resources to improve healthy food access”. This is a direct step of action to start solving the food security crisis in Oakland and other cities. Although the issue of food deserts is being addressed and reformed, this is just one of the smaller problems on the bigger issue of food security. There is a larger problem and a growing need to fix the distribution of food worldwide and increase self-procurement of food through the community. Big industry and environmental injustice keeps inequalities of race, income, and other social issues to be perpetuated through the unequal access to food, a basic 6 necessity of life. Through local and community involvement, in addition to policy change, the distribution and access of food will broaden and become an equalizer in the imbalance of social inequalities. 7 Bibliography: Almendrala, Anna. "California Food Deserts: Nearly 1 Million Live Far From Supermarkets, Grocery Stores." The Huffington Post. TheHuffingtonPost.com, 05 May 2011. Web "Bay Area Census -- City of Oakland." Bay Area Census -- City of Oakland. N.p., 2010. Web. CDC. "A Look Inside Food Deserts." Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 24 Sept. 2012. Web. Contra Costa County. "Demographics." Contra Costa County, CA Official Website. N.p., 2011. Web. Dutko, Paula, Michele Ver Ploeg, and Tracey Farrigan. "Characteristics and Influential Factors of Food Deserts." United States Department of Agriculture. N.p., Aug. 2012. Web. Gallagher, Mari. "Examining the Impact of Food Deserts on the Public Health of Chicago." Yale Rudd Center. LaSalle Bank, 2006. Web. Guggiana, Marissa. "For Oakland Food Desert: A Peoples Grocery Store | Berkeleyside." Berkeleyside. N.p., 18 Dec. 2012. Web. "How Much Does the Average American Make? Breaking Down the U.S. Household Income Numbers." My Budget 360. N.p., 2008. Web. "Improving Access to Healthy Food." PolicyLink. N.p., 2010. Web. Kersten, Elle, Barbara Laraia, PhD, Maggi Kelly, PhD, Nancy Adler, PhD, Irene H. Yen, "Small Food Stores and Availability of Nutritious Foods: A Comparison of Database and In-Store Measures, Northern California, 2009." Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 02 Aug. 2012. Web. Mendes, Elizabeth. "Americans Spend $151 a Week on Food; the High-Income, $180." Americans Spend $151 a Week on Food; the High-Income, $180. Gallup Polls, 2012. Web. "Oakland Is for Burning? Beyond a Critique of Gentrification : BayofRage." BayofRage. N.p., Oct. 2012. Web. OFPC. "Oakland Food Policy Council." Oakland Food Policy Council. N.p., 2011. Web. Raguso, Emilie. "The Oakland Food Map | Oakland Local." Oakland Local. N.p., 2010. 8 Web. Tarnapol Whitacre, Paula, Peggy Tsai, and Janet Mulligan. "The Public Health Effects of Food Deserts: Workshop Summary." The Public Health Effects of Food Deserts: Workshop Summary. The National Academies Press, Washington, D.C., 2009. Web.