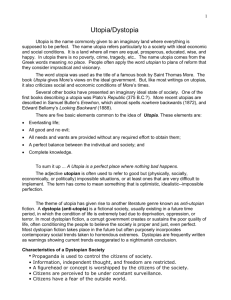

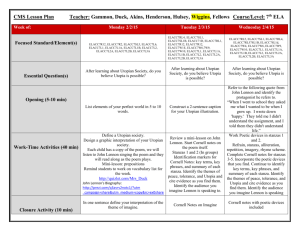

UTOPIA, CRISIS, JUSTICE - Utopian Studies Society

advertisement