4231,"net welfare effect",5,,,140,http://www.123helpme.com/view.asp?id=98373,9,165000000,"2016-02-25 05:50:58"

advertisement

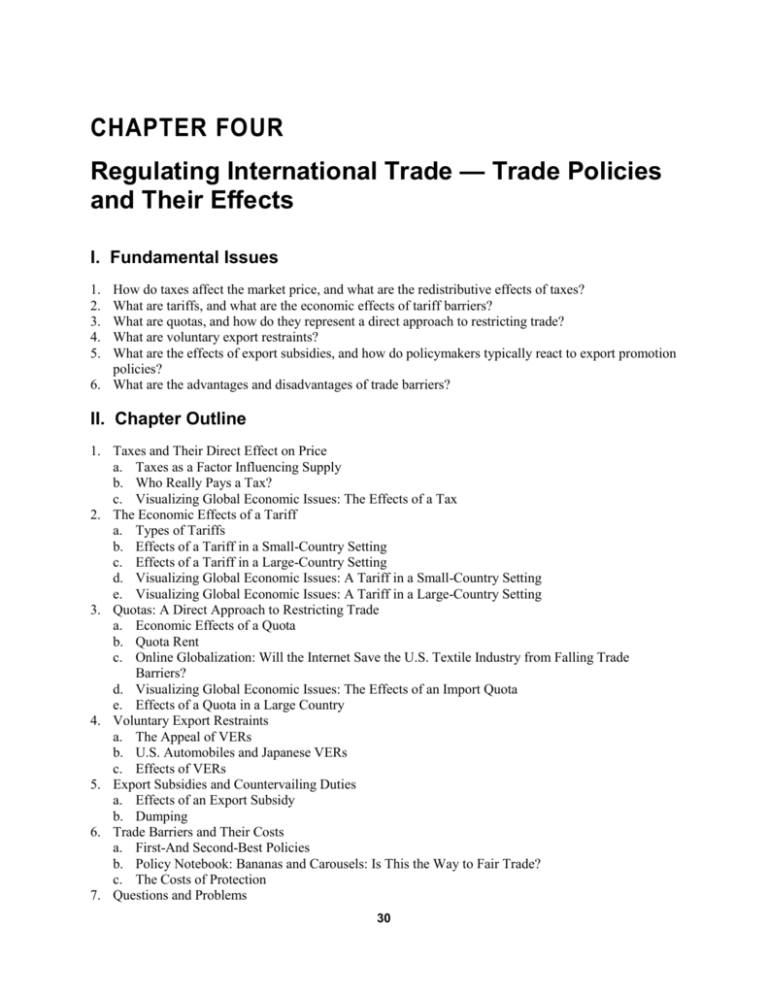

CHAPTER FOUR Regulating International Trade — Trade Policies and Their Effects I. Fundamental Issues 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. How do taxes affect the market price, and what are the redistributive effects of taxes? What are tariffs, and what are the economic effects of tariff barriers? What are quotas, and how do they represent a direct approach to restricting trade? What are voluntary export restraints? What are the effects of export subsidies, and how do policymakers typically react to export promotion policies? 6. What are the advantages and disadvantages of trade barriers? II. Chapter Outline 1. Taxes and Their Direct Effect on Price a. Taxes as a Factor Influencing Supply b. Who Really Pays a Tax? c. Visualizing Global Economic Issues: The Effects of a Tax 2. The Economic Effects of a Tariff a. Types of Tariffs b. Effects of a Tariff in a Small-Country Setting c. Effects of a Tariff in a Large-Country Setting d. Visualizing Global Economic Issues: A Tariff in a Small-Country Setting e. Visualizing Global Economic Issues: A Tariff in a Large-Country Setting 3. Quotas: A Direct Approach to Restricting Trade a. Economic Effects of a Quota b. Quota Rent c. Online Globalization: Will the Internet Save the U.S. Textile Industry from Falling Trade Barriers? d. Visualizing Global Economic Issues: The Effects of an Import Quota e. Effects of a Quota in a Large Country 4. Voluntary Export Restraints a. The Appeal of VERs b. U.S. Automobiles and Japanese VERs c. Effects of VERs 5. Export Subsidies and Countervailing Duties a. Effects of an Export Subsidy b. Dumping 6. Trade Barriers and Their Costs a. First-And Second-Best Policies b. Policy Notebook: Bananas and Carousels: Is This the Way to Fair Trade? c. The Costs of Protection 7. Questions and Problems 30 Regulating International Trade — Trade Policies and Their Effects 31 III. Chapter in Perspective This chapter covers the effects of three of the major trade barriers: tariffs, quotas and voluntary export restraints. The chapter first introduces the welfare effects of taxes, and then presents tariffs as a special kind of tax. The effects of a tariff in a country that is a price taker are contrasted with the effects of tariffs imposed by countries whose policies will materially affect global supply and demand conditions. The effects of two non-tariff barriers; quotas, and voluntary export restraints are also covered. The chapter ends with a discussion of export subsidies and countervailing duties, and a brief discussion of the suboptimal nature of trade barriers as a policy tool. IV. Teaching Notes 1. Taxes and Their Direct Effect on Price a. Taxes as a Factor Influencing Supply An increase in tax such as a sales tax will result in a shift in the supply curve to reduce quantity supplied at every price. The supply curve shifts vertically by the amount of the tax per unit. This does not mean that the price will rise by the full amount of the tax, however, unless the demand curve is perfectly inelastic. b. Who Really Pays a Tax? The tax is redistributive, meaning that it transfers purchasing power from consumers and/or producers to the government (taxing authority). The tax can cause both an increase in price and/or a reduction in producer profit margin. The producer may be able to forward shift the tax to the consumer by charging a higher price. Part of the tax may also be backward shifted when the producer receives a lower amount per unit. The proportions of the tax that are forward and backward shifted will depend on the shape of the demand curve. The steeper the demand curve, the more the tax will be forward shifted. S1 S0 P1 P0 PP D Q1 Q0 In the diagram, P0 is the original price, after the tax the reduction in supply causes the price to rise to P1 and quantity falls to Q1. Pp is the price the producer receives. The total tax revenue is (P1 – PP) * Q1. Part of the tax is forward shifted to the consumer (P1 – P0) * Q1, and part is backward shifted to the producer (P0 – PP) * Q1. 32 Chapter 4 c. Visualizing Global Economic Issues: The Effects of a Tax For Critical Analysis: Suppose the tax was 5 percent of the price, as opposed to a fixed amount per unit. How would (Text) Figure 4-1 be different? When the tax is calculated as a fixed amount per unit, the supply curve shifts vertically in a parallel manner. When the tax is calculated as a percent of the value, the shift of the supply curve is nonparallel because the tax per unit becomes greater as the value or price increases. 2. The Economic Effects of a Tariff a. Types of Tariffs A tariff is a tax on imported goods and services. A specific tariff is an amount of money charged per unit of the item imported. An ad valorem tariff is calculated as a percentage of the value of the item imported. Many items have combinations of specific and ad valorem taxes. For example, imported cigars have both an ad valorem tax of 4.7 percent and a specific tariff of $1.89. For a given import category, specific tariffs favor imports of high-end items. Ad valorem tariffs require an estimate of value in order to apply. b. Effects of a Tariff in a Small-Country Setting A “small” country is one whose production and consumption decisions do not affect global supply and demand conditions, i.e., the choice to impose a trade barrier will not affect the international price of the item in question. In this case, the full amount of a tariff is forward shifted to the consumers. Foreign producers remit the tariff to the domestic government so their per-unit revenue is unchanged. Domestic producers gain because the price of the domestically produced good as well as the imported good rises. Consequently, consumer surplus is reduced with some of this reduction transferred to domestic producers and the domestic government. Deadweight losses also occur in consumption and production efficiency. The effects of a tariff in a small country illustrated: Price S Domestic $100 S1 Global E F C G S0 Global $75 D Domestic Quantity 100 125 250 290 Regulating International Trade — Trade Policies and Their Effects 33 The figure depicts the supply and demand conditions in a small country before and after the imposition of a $25 specific tariff (or equivalently a 33 percent ad valorem tariff) per unit. Before the tariff, the global price of the good is $75 per unit and domestic demand is 290 units. At that price, domestic producers supply 100 units and 190 units are imported from foreign producers. After the tariff is imposed the price per unit rises to $100 and imports fall to (250 – 125) = 125 units. The tariff is forward shifted to the consumers. The loss of consumer surplus is measured by the sum of the areas of E, F, C and G and is equal to $6,750. [Calculated as (250 * $25) + ½ * (25 * 40). Recall that the area of a rectangle is base times height and the area of a triangle is ½ (base * height).] The loss in consumer surplus can be broken down as follows: Area E is the increase in domestic producer surplus arising from the ability to sell at the higher price and increase their amount supplied. This amount is $2,812.50. Area F is a deadweight loss due to inefficient production, i.e. from allocating additional scarce resources away from their highest opportunity cost use (more efficient unprotected industries), and it is equal to $312.50. Area C is the government revenue from the tariff. It is equal to $3,125. Area G is a deadweight loss due to inefficient consumption. This triangle represents the change in the optimal consumption pattern as consumers shift purchases to less desirable substitutes due to the artificial price rise induced by the tariff. The area of triangle G is $500. Foreign producer surplus is unchanged as they receive $100 per unit and remit $25 to the domestic government, so they still receive $75 per unit after the tariff, but they do lose market share to domestic producers. Check: Total loss in Consumer Surplus = $2,812.50 + $312.50 + $3,125 + $500 = $6,750 The net effect is to transfer consumer surplus to domestic producers and the domestic government. The loss in consumer surplus is greater than the gains to the government and the domestic producers so there is a net welfare loss for domestic residents. c. Effects of a Tariff in a Large-Country Setting A large country’s global market share is of sufficient size that the country’s production and consumption decisions will affect the global price. This changes the results of the analysis. When a large country imposes a tariff on imported goods, the price of the good in that country will rise as was the case for the small country, but less than the full amount of the tariff is forward shifted to the consumer. The price increase causes a reduction in domestic demand, an increase in domestic production and a reduction in imports, as in the small country case. The difference is that the reduction in imports is assumed to be large enough to affect the international price of the good. Unlike the small-country setting, the international price of the good then falls, resulting in different redistributive effects. D 34 Chapter 4 Effects of a tariff in a large country: SDom $130 $100 $80 A B C E $100 $80 D 200 220 230 250 SFor F G H I DDom DFor 200 220 230 250 The global price is initially $100 per unit, domestic production is 200 units and the quantitiy demanded is 250 units, so imports are 50. The large domestic country then imposes a $50 per unit tariff. Notice that in this case the domestic price does not rise by the full tariff amount. Hence, not all of the tariff is forward shifted to domestic consumers. The loss in domestic consumer surplus is the sum of areas A + B + C + D. Area A is an increase in domestic producer surplus equal to $6,300. B and D are deadweight losses totaling $600. Areas C + E give the government’s total tariff revenue of $500. Area E does not represent a loss in domestic consumer surplus because the original price was not $80. The tariff revenue represented by Area E of $200 is backward shifted to the foreign producers and is equivalent in size to Area H. Areas G and I are deadweight losses in the foreign economy. In this case, the inefficiencies are spread to multiple countries. Since a result is to shift foreign producer surplus to domestic producers, this type of policy is called a beggar-thy-neighbor policy where a policy action benefits one nation’s economy but worsens economic performance in another nation. Teaching Tip: Foreign responses from Europe and elsewhere to President Bush’s decision to protect the U.S. steel industry are a case in point of the swiftness with which retaliation for protectionist polices are likely to occur. d. Visualizing Global Economic Issues: A Tariff in a Small-Country Setting For Critical Analysis: Suppose the domestic government imposed a 25 percent ad valorem tariff as opposed to a specific tariff. Would the graphical analysis differ from that shown in Text Figure 4-2? It would not because a 25 percent ad valorem tariff would result in a $50 tariff, which is the same as the specific tariff. Regulating International Trade — Trade Policies and Their Effects 35 e. Visualizing Global Economic Issues: A Tariff in a Large-Country Setting For Critical Analysis: In Text Figure 4-3, the tariff transferred surplus away from Japanese steel producers to the U.S. government. On net, is the U.S. economy better off because of the tariff? We answer this question by calculating the total foreign surplus transferred to the U.S. government which is found as [(135,000 – 115,000) * ($200 – $180)] = $400,000 and comparing the result to the amount of deadweight losses in the U.S. The domestic deadweight losses are the sum of Areas B and D. Total foreign surplus transferred to the U.S. government: Area E (or H) = [(135,000 – 115,000) * ($200 – $180)] = $400,000 Area B = ½ * (115,000 – 100,000) * ($230 – $200) = $225,000. Area D = ½ * (150,000 – 135,000) * ($230 – $200) = $225,000. Total deadweight losses are $450,000. The economy is thus worse off by $50,000. 3. Quotas: A Direct Approach to Restricting Trade An import quota is a restriction on the physical quantity that may be imported. a. Economic Effects of a Quota Tariffs indirectly affect the quantity of imports by affecting the price of imports. Quotas directly affect the quantity of imports and indirectly affect the price. b. Quota Rent Quotas are part of a general type of trade barrier referred to as non-tariff barriers. GATT and the WTO have attempted to reduce tariffs and non-tariff barriers to trade with mixed success. An absolute quota limits the amount of a product that can enter a country during a specified time period. Sugar and Canadian lumber have absolute quotas. Tariff rate quotas allow imports at no or a low tariff up to a specific maximum amount; amounts beyond the quota may still be imported but are subject to a high tariff. Quotas, like tariffs, cause the price of the good subject to a quota to rise as quantity supplied is reduced. The increase in price causes domestic producers to supply more of the good and the net result is a reduction in consumer surplus and an increase in domestic producer surplus and foreign producer surplus for those foreign producers who fill the quota. Deadweight losses still occur as with a tariff. The domestic government may attempt to recapture the increase in foreign producer surplus by charging a quota rent to foreign producers. 36 Chapter 4 Teaching Tip: The U.S. government has not traditionally charged quota rents. The right to import sugar to the U.S. is a very valuable business asset and the U.S. government could auction off rights to import sugar to the U.S. Typically, the quotas have been allocated based on political expediencies or on a first come first served basis. c. Online Globalization: Will the Internet Save the U.S. Textile Industry from Falling Trade Barriers? For Critical Analysis: Do Latin American and Asian textile companies have a legitimate complaint? U.S. access to the Internet and growing experience in B2B interactions represent a comparative advantage for U.S. firms; proximity to large consumer markets is a similar comparative advantage. In a general sense, all comparative advantages are trade barriers from someone’s perspective. Latin American and Asian textile companies have no legitimate complaint unless the U.S. refuses to allow foreign firms access to the relevant systems or the software needed, etc. d. Visualizing Global Economic Issues: The Effects of an Import Quota For Critical Analysis: In which industries do you suppose policymakers are more likely to impose quotas: goods or services? Why? One would suppose that all barriers would be easier to implement for goods rather than services. In practice, quotas tend to be used more for services, and they are implemented by strictly limiting foreign access to service markets. For example, financial services continue to be heavily protected in many countries. e. Effects of a Quota in a Large Country Similar to a tariff, if a large country imposes a quota, the international price of the good or service will decline, resulting in a reduction in foreign producer surplus (and an increase in foreign consumer surplus). The foreign producers may still capture the quota rent and the net effect on foreign producers is indeterminate ex-ante. 4. Voluntary Export Restraints Voluntary export restraints (VERs) are typically bilateral informal agreements between a domestic country and a foreign government and its producers. They typically take the form of an import quota. a. The Appeal of VERs VERs are appealing because they do not require formal legislative approval they are easy to change or repeal they are voluntary and so they do not violate WTO rules (or other agreements). b. U.S. Automobiles and Japanese VERs During the 1980s, the U.S. negotiated a VER with Japanese auto producers to limit the number of autos imported from Japan. The result was similar to a quota, and the quota rent was captured by the Japanese auto producers and domestic auto producers. Regulating International Trade — Trade Policies and Their Effects 37 Teaching Tip: Microeconomic (individual) firm responses are critical to understanding the true effects of VERs and other trade barriers. The Japanese automaker’s response to the VERs was to standardize what were optional features in most autos at the time and produce higher quality cars, changing their advertising as well. Prior to the VERs, the Japanese firms positioned their products as economical cost savers. The real problem with the domestic auto industry was not foreign imports, but Detroit’s inability or unwillingness to produce a reasonable quality, fuel-efficient automobile at an affordable cost. For details and cost estimates of these VERs see “An Introduction to Non-Tariff Barriers to Trade,” Cletus Coughlin and Geoffrey Wood, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Review, January/February 1989, pp. 32-46. c. Effects of VERs A VER is equivalent to a quota and has similar effects, except that a VER is generally only enforced for one nation, so other nations can benefit from the higher prices caused by VERs. For instance, European auto manufacturers benefited from the aforementioned VERs on autos in the 1980s. 5. Export Subsidies and Countervailing Duties An export subsidy is a payment by a domestic government to a domestic firm for exporting goods or services. a. Effects of an Export Subsidy The export subsidy acts like a negative tariff. It increases consumer surplus in the importing nation, reducing that country’s domestic producer’s surplus and it increases the foreign exporter’s producer surplus. b. Dumping Dumping can be defined as selling a product at a lower price in a foreign country than the price charged in its domestic country. Dumping is also sometimes defined as selling a good or service below its cost of production. Presumably dumping harms local firms. If an industry can show that foreign export subsidies or dumping are harming a local industry, they can lobby for countervailing duties (CVDs) to reduce the deleterious effect. CVDs usually take the form of a tariff, and they are designed to offset export subsidies; they are usually allowed under international trade agreements such as WTO rules. 38 Chapter 4 6. Trade Barriers and Their Costs Even though this chapter shows that trade barriers are usually inefficient and costly, and worse they often lead to retaliation, barriers still continue to be used. This probably says more about the level of understanding about the real effects of international trade than anything else. Also, certain interest groups such as unions for example see their power diminished by international business, and these groups tend to be both well organized and vocal. Moreover, some labor groups can definitely be hurt by international trade, and the media always seems to find them when trade issues are discussed. a. First- and Second-Best Policies A first-best trade policy is one that deals with the underlying lack of competitiveness. A secondbest policy is one that attempts to remedy a problem through indirect means. Trade barriers are second-best policies and their use is suboptimal because they do not address the underlying problem of comparative advantage (or the lack thereof). b. The Costs of Protection According to the Institute for International Economics in Washington, trade barriers have not been cost effective methods of preserving domestic jobs (See Text Table 4-5). The average annual cost of preserving a single job was recently found to be $170,000, which is far more than most workers make. The text points out that it would normally be cheaper to buy the imported goods and pay idle workers their salaries rather than enact a trade barrier to protect the local industry. c. Policy Notebook: Bananas and Carousels: Is This the Way to Fair Trade? For Critical Analysis: Should firms have the right to approve bilateral trade agreements? Should firms receive the revenue generated by countervailing duties imposed to offset export promotion policies? Firms should not have the right to approve bilateral trade agreements. Interests of producers do not necessarily coincide with the interests of a country’s citizens. Firms should not receive the revenue generated by countervailing duties, because they are already receiving the benefits; their producer surplus is preserved by the CVDs. Giving them the revenue would be “doubledipping,” and would also encourage industries to file frivolous charges to improve their profits. 7. Answers to End of Chapter Questions 1. a. We can tell that this is a large country, because the domestic price did not fall by the full amount of the tariff that was removed. b. The home and the international markets are represented by standard supply and demand framework. Because the home country is an importer of this product, the autarky price in the home market is less than the equilibrium price on the international market. Regulating International Trade — Trade Policies and Their Effects 39 2. a. Consumer surplus increases by $6.8 million, [($0.40 * 14) + ($0.40 * 6) / 2] = 6.8. S P 2.90 2.50 D 4 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 6 14 20 QMillions b. Producer surplus declines by $2 million, [($0.40 * 4) + ($0.40 * 2) / 2] = 2. c. The lost tariff revenue is $4.8 million, [(14 – 6) * $0.60] = 4.8. Neither. The gain in consumer surplus exactly matches the loss of producer surplus and the lost tariff revenue. In other words, the deadweight gains from the removal of the tariff exactly match the amount of tariff revenue that had been forward shifted onto foreign producers. This is false. If the country that imposes the tariff is a large country, it may experience a net welfare gain, loss, or neither, as question (3) shows. b. i. The loss of consumer surplus is $16.5 million, [($15 * 1) + ($15 * 0.2) / 2] = 16.5. ii. The gain in producer surplus is $5.25 million, [($15 * 300) + ($15 * 100) / 2] = 5,250. iii. The deadweight losses total $2.25 million, [($15 * 100) / 2 + ($15 * 200) / 2] = 2,250. iv. The quota rent is $9 million, ($15 * 600) = 9,000. The equivalent specific tariff is $15. The equivalent ad valorem tariff is 50 percent. The benefit would be to capture the value of the quota rent if the government did not have some type of licensing arrangement in place. There are two main arguments against this policy. First, it gives an incentive for companies to file frivolous claims seeking protection. Second, because the CVD provides protection to the companies in the protected sector, giving them the duties would amount to a second layer of protection. Because the VER increased the price of autos, and [producers in country 1 and 2 were able to increase their quantity supplied, producers in these two countries benefit as producer surplus rises. The total revenue of producers in country 3 falls and the consumer surplus of domestic consumers falls. Hence, these two groups are harmed. b. Domestic producer surplus falls by $200,000. [($0.5 * 0.3) + ($0.5 * 0.2) / 2] = $0.2. Domestic consumer surplus rises by $575,000, [($0.5 * 1) + ($0.5 * 0.3) / 2] = $0.575. c. The value of the surplus equals the amount of imports times the decrease in domestic price, or $500,000, ($0.5 * 1) = $0.5. d. There are actually deadweight gains to the domestic economy. They equal the difference between the loss of producer surplus and the increase in domestic consumer surplus. The equivalent ad valorem tariff is 50 percent. The CVD should be distributed back to consumers of domestic sugar, as they are the ones paying the duty.