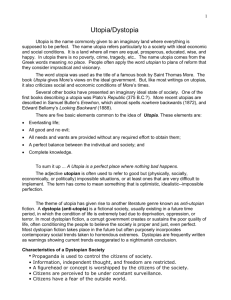

Towards the end of Sylvia Plath`s _The Bell Jar_ (1963), Esther

advertisement