Justification, Materials, Assessment - Queens College

advertisement

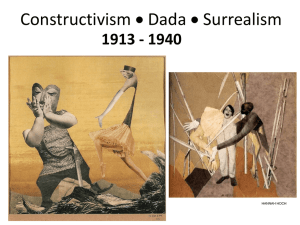

Perspectives on the Liberal Arts and Sciences: Course Proposal Narrative General Education Advisory Committee Queens College, City University of New York Course Title: Dada and Surrealism: Image, Mind, and Authority Primary Contact Name and Email: Prof. James Saslow, james.saslow@qc.cuny.edu Co-chair, Art Dept. Curriculum Committee Date course was approved by department: Curriculum Committee meeting, September 2008. PLAS Area Requirement: Participation in and appreciation of the arts. Number, Title, Credits, Prerequisites of proposed course: ARTH 260. Dada and Surrealism: Image, Mind, and Authority. 3 hrs., 3 crs. No prereq.; ARTH 001 or 102 recommended as preparation. COURSE DESCRIPTION This course examines Dada and Surrealist art and literature from their origins in World War I to their interwar flowering and later influence. These two movements radicalized our modern understanding of painting, sculpture, collage, photography, and film, and paved the way for many subsequent developments down to Postmodernism. The course traces their philosophical and theoretical sources in idealism, materialism, and psychoanalysis. Special emphasis is placed on issues that relate these arts to the early 20th-century context of Europe and the Americas and to other liberal arts disciplines: paternal authority and transgressive sexuality; the role of women both as subject matter and as artists in their own right; and problems of language and representation, including relationships of text and image. Classroom activities are supplemented by film screenings and museum visits, emphasizing direct contact with artworks in the Museum of Modern Art. JUSTIFICATION In line with the PLAS learning objectives, the proposed course will: 1. Address how, in the discipline (or disciplines) of the course, data and evidence are construed and knowledge acquired; that is, how questions are asked and answered. The course will introduce students to a variety of methodological tools important to the discipline of art history, including aspects of Semiotics (viz. the problem of text and image in “second-wave” Surrealism); Commodity- and Institutional-Critique (viz. the development of Marcel Duchamp’s “Ready-mades”, and Kurt Schwitters’ “Merz” works); aspects of Hegelianism and Marxism (viz. the dialectical underpinnings of Surrealism); Gender Studies (viz. the construction of gender and sexual orientation in Dada and Surrealist photography, photomontage and sculpture); Psychoanalysis (viz. the development of Surrealist “automatism” and related techniques for accessing the unconscious); and Post-colonial discourse (viz. the significant position and influence of non-western art on Dada and, especially, on Surrealism, as well as the internationalization of Surrealism in the Caribbean and Latin America). 2. Position the discipline(s) in the liberal arts curriculum and the larger society. The foregoing methodologies are inherently interdisciplinary in approach and, indeed, are often derived from other liberal-arts disciplines, including gender studies, literary analysis, political science, philosophy, and psychology. Thus, rather than cordoning off individual areas of knowledge, students would be encouraged to approach the various liberal-arts disciplines synthetically, in relation to the continuity of knowledge they posit, as well as the shared socio-cultural contexts on which they rely. Indeed, a number of these socio-cultural contexts are the same as would be encountered in a modern political-science or history course – for example, the epochal influence of World War I (especially, on Zurich and Berlin Dada); modes of addressing the rise of Fascism in Europe (as in the photomontages of John Heartfield, as well as in the paintings of Max Ernst and Salvador Dalí); questions of political engagement, and commitment (viz. Surrealism’s problematic relationship with Communism), etc. 3. Address the goals for their categorization as fulfilling an Area of Knowledge and Inquiry requirement, and (as appropriate) a Context of Experience and/or an Extended Requirement. Students will become familiar with the major artists, artworks and styles that characterize Dada and Surrealism. Therefore, the “Area of Knowledge and Inquiry” on which the course would focus would be “Appreciating the [Visual] Arts”. Although its “Context of Experience” would focus primarily on Europe, the course would also include significant contributions by European artists working in the United States (during WW I and WW II), as well as artists from the Caribbean and Latin America. 4. Be global or comparative in scope. The course would emphasize the ways in which Caribbean and Latin American artists specifically position their work in relation to both European as well as indigenous traditions (e.g., Wilfredo Lam and Frida Kahlo); in addition, major figures like the Chilean artist Matta, who occupies a similarly pivotal position between Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism, would be considered. Moreover, the course would be comparative / interdisciplinary in its efforts to address not only the visual arts, but also Dada and Surrealist film and performance (especially, varieties of Dada sound poetry), as well as literature and philosophy (e.g., André Breton and Georges Bataille). 5. Consider diversity and the nature and construction of forms of difference. By emphasizing both the international reach of Dada and Surrealism, as well as the contributions of artists of color, women artists, and gay / lesbian artists, the course would seek to emphasize diversity not only as a national construct, but also as a question of race, gender and sexual orientation. 6. Reveal the existence and importance of change over time. The course would emphasize how certain strategies, although fundamental to both Dada and Surrealism, were nevertheless adapted to meet specific, historical exigencies: most notably, how the use of “chance,” which often functioned for the Dadaists as a form of social protest and, at times, a political weapon in the context of World War I, was transformed into a psychoanalytic strategy by the Surrealists in the 1920s, albeit emanating from their traumatic experience of the same historical conditions (WW I). 8. Use primary documents and materials. The course would draw on a number of artists’ interviews, statements and other writings, as well as major art-historical treatments of the artists and styles under consideration. The most fundamental, primary source material is of course the artwork itself; museum visits will engage students with the ultimate primary texts of this field. COURSE MATERIALS The text for this course would be a course-pack containing the following PDF-formatted (or photocopied) materials: 1. Marcel Duchamp: “The Richard Mutt Case” (1917), in Kristine Stiles and Peter Selz, eds., Theories and Documents of Contemporary Art: A Sourcebook of Artists' Writings (University of California Press, 1996), p. 817; “The Creative Act” (1957), ibid., pp. 818-19; “Apropos of ‘Readymades’” (1961), ibid, pp. 819-20. Marcel Duchamp, “Painting at the service of the mind” (1946), in Herschel Chipp, ed., Theories of Modern Art: A Source Book by Artists and Critics (University of California Press, 1968), pp. 392-395. Marcel Duchamp, “I Propose to Strain the Laws of Physics” (1968), Art News, vol. 67, no. 8 (Dec. 1968). These are among the artist’s best-known statements of the revolutionary change he proposes in the status of the artist (as selecting, not creating, subject matter) and the artwork (as fundamentally multiple and quotidian, rather than singular and ingenious). 2. Selections from: Rosalind Krauss, “Forms of Readymade: Duchamp and Brancusi”, in Passages in Modern Sculpture (MIT 1981). William Camfield, “Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain: Aesthetic Object, Icon, or Anti-Art?”, in The Definitively Unfinished Marcel Duchamp, ed. Thierry de Duve (MIT 1991). Paul Franklin, "Object Choice: Marcel Duchamp's Fountain and the Art of Queer Art History", Oxford Art Journal, vol. 23, no. 1 (2000). These readings would serve as a case study of the comparative approach: Krauss situates Duchamp’s “Ready-mades” within the field of art history; Camfield situates them within a broader social context, including their actual sources, and contemporaneous understandings of them; Franklin proposes an innovative queer reading of them. 3. Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” (1936), in Charles Harrison and Paul Wood, eds., Art in Theory, 1900 - 2000: An Anthology of Changing Ideas (Wiley-Blackwell, 2nd edition, 2002), pp. 512-20. Benjamin’s essay is among the great statements, in the twentieth century, of how reproducibility is not the dispensable by-product of an artwork, but increasingly inherent in the very fact of its creation: this is, indeed, the epochal influence of the “Ready-mades”. 4. David Hopkins, "Questioning Dada's Potency: Picabia's 'La Sainte Vierge' and the Dialogue with Duchamp", Art History, vol. 15, no. 3 (Sept. 1992). Hopkins is a leading scholar of Dada in Paris and New York; and his article, recently incorporated into a book-length treatment of Dada and gender, nicely complements the Franklin article (above). 5. Selections from: Leah Dickerman, ed., Dada: Zurich, Berlin, Hanover, Cologne, New York, Paris (National Gallery of Art 2005). This is an excellent catalog, the individual chapters of which are broken down geographically: selections addressing Dada in Switzerland and Germany would nicely complement the above articles, which tend to focus, by contrast, on Paris and New York. 6. Tristan Tzara, “Dada Manifesto” (1918), in Charles Harrison and Paul Wood, eds., Art in Theory, 1900 - 2000: An Anthology of Changing Ideas (Wiley-Blackwell, 2nd edition, 2002), pp. 248253; “Manifesto on Feeble Love and Bitter Love” (1920), in Robert Motherwell, ed., The Dada Painters and Poets: An Anthology (Harvard University Press, 2nd Edition, 1981). Tzara was truly the Johnny Appleseed of Dada, internationalizing the movement, as well as one its early pioneers from its Zurich days: his manifestoes remain emblematic of the spirit of Dada. 7. Hugo Ball, “Dada Fragments” (1916-17), in Charles Harrison and Paul Wood, eds., Art in Theory, 1900 - 2000: An Anthology of Changing Ideas (Wiley-Blackwell, 2nd edition, 2002), pp. 246248. Richard Huelsenbeck: “First German Dada Manifesto” (1918-20), ibid., pp. 253-255; “En Avant Dada” (1920), ibid., pp. 257-260; with Raoul Hausmann, “What is Dadaism and what does it want in Germany?” (1918-19), ibid., pp. 256-257. These are major statements by the leading figures associated with the rise of Dada in Zurich and Berlin. 8. Kurt Schwitters, “Merz” (1921), in Herschel Chipp, ed., Theories of Modern Art: A Source Book by Artists and Critics (University of California Press, 1968), pp. 382-384. Schwitters was a veritable one-man Dada movement and, like Tzara, of capital importance in internationalizing the movement. 9. Giorgio de Chirico: “Meditations of a painter” (1912), in Herschel Chipp, ed., Theories of Modern Art: A Source Book by Artists and Critics (University of California Press, 1968), pp. 397-401; “Mystery and Creation” (1913), ibid., pp. 401-402. De Chirico is generally credited as a major precursor of Surrealism, and these remain among his most lyrical, and suggestive statements concerning the symbolism of his figures, and the spaces they inhabit. 10. Briony Fer, “Surrealism, Myth and Psychoanalysis”, in David Batchelor, Paul Wood, Briony Fer, Realism, Rationalism, Surrealism: Art Between the Wars (Yale University Press, 1993). Fer is a leading art historian, and her contribution to the foregoing survey is the most comprehensive, yet concise treatment available of the fundamental goals and ideals of Surrealism. 11. André Breton: “Manifesto of Surrealism” (1924), Charles Harrison and Paul Wood, eds., Art in Theory, 1900 - 2000: An Anthology of Changing Ideas (Wiley-Blackwell, 2nd edition, 2002), pp. 432439; “Second Manifesto of Surrealism” (1929), ibid., pp. 446-450; “What is Surrealism” (1934), in Herschel Chipp, ed., Theories of Modern Art: A Source Book by Artists and Critics (University of California Press, 1968), pp. 410-417. Breton has been dubbed the “pope” of Surrealism, and his manifestoes have long been considered Surrealist “dogma”; they are also rather long, and the foregoing anthologies have done an excellent job of excerpting them. 12. Selections from: Georges Bataille, Visions of Excess: Selected Writings, 1927-1939 (University of Minnesota Press, 1985). Bataille has come to be positioned as, perhaps, the critical foil to Breton’s vision of Surrealism; Bataille’s early essays, for the journal Documents, are a brilliant inversion of Breton’s emphasis on theory – in favor of praxis, and lived bodily experience as the relevant touchstone. 13. Selections from: Andre Breton, Nadja (1928), trans. and Richard Howard (Grove Press, 1994). This is an emblematic work of Surrealist literature. 14. Louis Aragon, “The Challenge to Painting” (1930), in The Surrealists look at art: Éluard, Aragon, Soupault, Breton, Tzara, ed. Pontus Hulten (Lapis 1990). Max Ernst, “Beyond Painting” (1936), in Herschel Chipp, ed., Theories of Modern Art: A Source Book by Artists and Critics (University of California Press, 1968), pp. 427-431. These are two major statements, by a Surrealist author and artist, of the sorts of new techniques and strategies that characterize Surrealist art. 15. René Magritte, “Words and Images” (1929), in Suzi Gablik, Magritte (Thames and Hudson, 1985). Salvador Dalí, “The Rotten Ass” (1930), in Charles Harrison and Paul Wood, eds., Art in Theory, 1900 - 2000: An Anthology of Changing Ideas (Wiley-Blackwell, 2nd edition, 2002), pp. 478-481. These are two major statements, by “second-wave” Surrealist artists, explaining the goals and ideals of their art. 16. Rosalind Krauss, “A game plan: the terms of Surrealism”, in Passages in Modern Sculpture (MIT 1981). Krauss is a leading art historian, and this chapter in her survey of modern sculpture remains among the most thought-provoking, yet thoroughly accessible introductions to Surrealist sculpture. 17. Salvador Dalí, “The Object as Revealed in Surrealist Experiment” (1932), in Herschel Chipp, ed., Theories of Modern Art: A Source Book by Artists and Critics (University of California Press, 1968), pp. 417-427. André Breton, “Crisis of the Object” (1936), in Surrealism and Painting (1965), trans. Simon Taylor (MacDonald 1972). These two essays are important to understanding the difference between “sculpture” and Surrealist “objects” – effectively, a precursor of assemblage-based strategies of art production. 18. Joan Rivière, “Womanliness as Masquerade” (1929), in Formations of Fantasy, ed. Victor Burgin (Routledge, 1987). Rivière was a psychoanalyst, and her essay constitutes a major contribution to understanding gender identification as constructed (rather than innate) – and, more importantly, as a strategy which is essentially defensive. ASSIGNMENTS AND ACTIVITIES Midterm Exam, and (non-cumulative) Final Exam: Students will be required to identify the artist, title and date of major artworks that were discussed in class, which are also reproduced on the class web-site. In addition, short-answer questions will test student’s familiarity with important ideas, themes and influences, as well as significant questions of style and subject matter, artistic and historical context and influence. Finally, essay-format questions will test students’ abilities to discuss major artworks both effectively on their own terms and in a way that discriminates substantial (stylistic, thematic, historical, etc.) relationships between them. Three Response Papers: Six topics will be assigned from among the assigned readings (above), from which students will be required to select three topics for their response papers. In turn, each response paper will require students not only to critique a specific reading, but also to elaborate on the ways in which it might serve as a vehicle for better understanding a major artwork of their own choosing. This is an effort to complement theory with praxis, by having students approach the readings not only as rhetorical exercises, but also as susceptible of practical application in the visual arts. However, it is also intended to develop the personal voice of the student, inasmuch as the response paper is significantly driven by the artwork the student chooses, including how the student forges a “fit” between reading and artwork. Students will be expected to meet with the instructor, following the first as well as the second response papers, in an effort to tailor and individualize instruction to the specific needs of the student. Class Participation: Keeping up with the assigned readings, and being able to discuss them effectively in class, is an integral component of this course, inasmuch as it gauges whether students are understanding the methodologies at issue, and assimilating them in a way that transcends any specific artwork in favor of a comprehensive understanding of how aesthetic criteria are both developed and, in turn, applied in any given case. Museum and Gallery Visits: One or two field trips will be organized as a means of submitting artworks to close-up, first-hand examination – with the goal of better understanding questions of surface, scale, environment, etc. ASSESSMENT It would be preferable to build assessment instruments into the normal activities of the course, rather than add extraneous measurement devices that students might resent as burdensome. The two exams and three response papers in this course would provide useful, concrete materials for the assessment of student learning and its development over time. While the exams are intended equally to emphasize the acquisition of factual knowledge, as well as the means to interpret, reason from and otherwise make informed decisions based on it, the response papers are intended wholly to emphasize the latter: rather than premised on the notion of arriving at a “correct” or an “incorrect” interpretation, the response papers are fundamentally about the process of interpretation itself, and engaging with that process in a personal way. ADMINISTRATION In the Art Department, oversight of course topics and content is performed by the Curriculum Committee, which will now have responsibility for approving all new PLAS courses, monitoring their compliance with stated goals and procedures, and defining materials for assessment. The Department formed an Assessment Committee two years ago to oversee the new emphasis on outcomes assessment, and that Committee will perform the actual evaluation of new PLAS courses, in conjunction with the GEAC procedures. The present course will be taught by full-time faculty (at the moment, mainly Prof. Powers), because its period-specific content requires a familiarity with the subject matter, and the time to be able to engage individually with student writing assignments, perhaps difficult to find among adjuncts; it could, however, be taught by other full-timers with a specialization in art between the wars, or sufficiently specialized adjuncts.