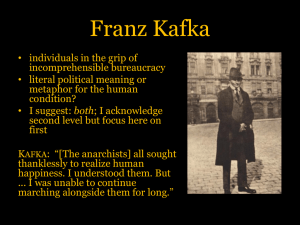

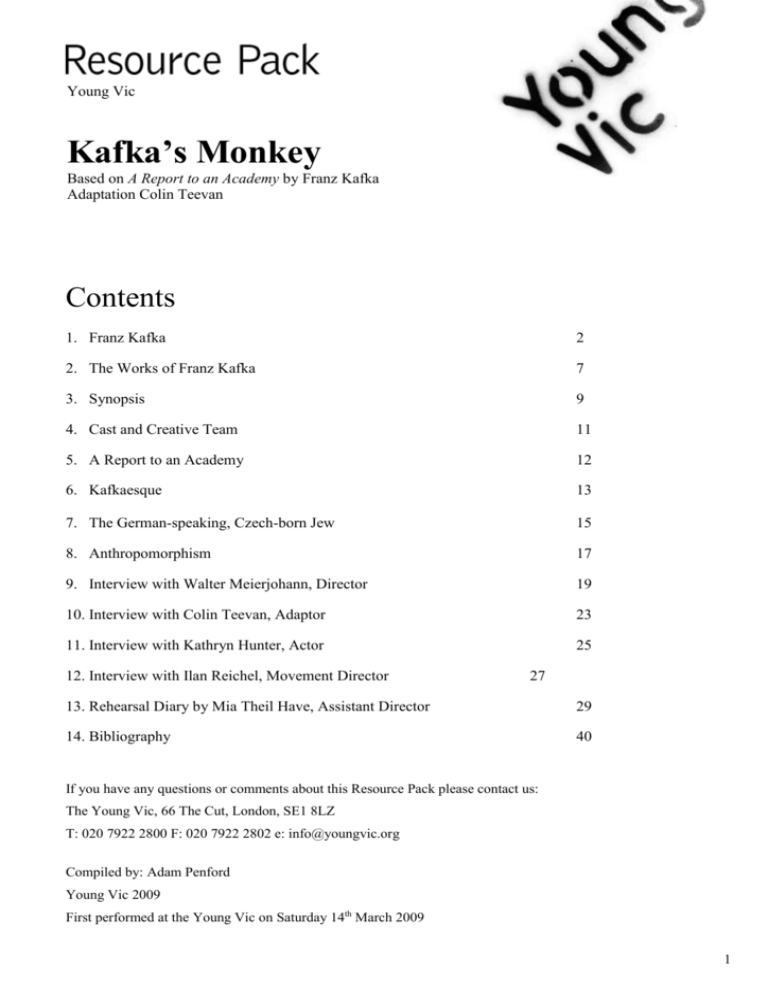

Kafka`s Monkey

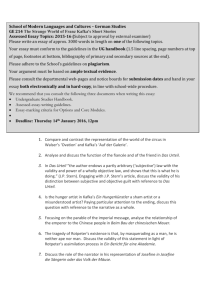

advertisement