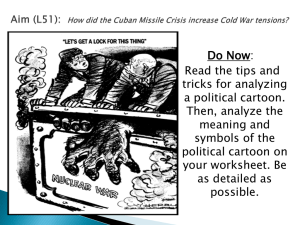

Following the overthrow of Fulgencio Batista in January of 1959

advertisement

Following the overthrow of Fulgencio Batista in January of 1959, Fidel Castro began to implement his new vision for Cuba based on his communist ideals. Like Mao Zedong in China, one of the groups that Castro looked to for support was the women of Cuba. By 1990, many felt that women’s positions had been bettered in terms of their lives. Still others commented that more had to be done to remove the remnants of patriarchy which still existed. Some, however, seem to offer a different account, highlighting how Castro’s Cuba had actually hampered both gender relations and family life. Many point to the positive results on the lives of Cuban women following the revolution of 1959. Navarro, (Doc 1) a Cuban socialist feminist, discusses the male authority that mothers and daughters had to live under before 1959. She points to the legacy of the Spanish law codes with imposed patriarchal power, and in spite of efforts by others to override this tradition, none were effective until the communist revolution. As a socialist sympathizer, it should not be surprising that she looks to Castro’s rule as favorable. Another woman interviewed by a US journalist (Doc 7) points to the Family Code that guarantees the equal rights of women and the opening of day-care centers and public schools to help working women and their children. Yolanda Ferrer (Doc 2), the General Secretary of the Federation of Cuban Women, confirms the basic job skills available to women. She further states that women garnered skills that allowed them to move away from domestic work into white collar jobs. As a female politician, Ferrer would owe her position to the Cuban government, so therefore she would clearly support their agenda. However, it is true that others, including Genoveva Diaz, (Doc 4) echoes a similar sentiment that Castro’s Cuba offered women new economic opportunities and allowed them to move away from being servants. Once again, as the daughter of a Cuban revolutionary, it seems natural that her support would side with that of the government. Similar testimony about economic opportunity is cited by Espin, (Doc 10) a female scientist and president of the Federation of Cuban Women, who details statistical evidence to demonstrate that increasing participation of women in economic life. Further favorable statistical data is compiled by the Communist Party (Doc 9) who points to increased female participation in politics since the mid-1970s. While this evidence might be suspect given that it was gathered by the Communist party, less biased statistical proof is offered by the United Nations (Doc 8) which acknowledges that Cuban women have very high literacy rates and are a significant part of the income earning population in the years following the overthrow of Batista. Some individuals say that while progress has been made, further steps still need to be taken to create true equality. Castro himself acknowledges this in a speech in 1974, (Doc 5) in which he points out that discrimination still exists and that full equality has not been achieved. Espin (Doc 10) points out that progress has not been made in the family sphere where women shoulder a double burden of wage earning and sole caretaker for children. Soviet women often found this to be the case while making sizeable advancements in entering the job market, but still having the “double-burden” of caring for the home. And, of course, law codes cannot undue the effects of years of patriarchal culture (Doc 7). Some do not look favorably on how the revolution affected women, and more specifically gender relations. A male Cuban sympathizer (Doc 3) discusses his staunch anti-women’s liberation position explaining that women’s economic freedom has undermined traditional marital roles. Since he is being interviewed by a US anthropologist, he might feel free to express what would otherwise be an unpopular sentiment. Fernadez in her memoir (Doc 6) points out how she was expelled from medical school upon asking for maternity leave. She discusses the difficulties of living in Cuba with her infant daughter when she was short of necessary supplies. As an exile, it is not surprising that she is highly critical of her former country’s government. Even Diaz (Doc 4) acknowledges that older women think that the revolution hurt gender relationships by allowing women to do “men’s work”. To fully assess the effects of Castro’s rule on Cuba further statistical evidence would be very helpful. For example, do men and women earn equal wages for the same work? Since this is an issue in the United States, which considers itself a leader in the feminist movement, it would interesting to compare such numbers with those of communist Cuba. Furthermore, data which revealed divorce rates pre and post revolution might offer insight on how gender relations have been altered. Also, while a man’s perspective was offered in one excerpt, it seems a broader assessment by men would be very telling on the subject of gender relations and family life. Finally, because communist regimes typically censor criticism, a more accurate assessment might be achieved by having the first-hand testimony from non-Cuban sources. While gender relations and challenges to traditional patriarchy are universal issues, it is interesting to note the variety of perspectives and experiences in Cuba from 1959 to 1990. It seems that while women have made great strides in the public arena, challenges still exist on the home front.