Development Measures Essay.doc

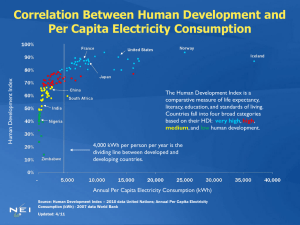

advertisement

Name: Caroline Epe Degree programme: MSc Development Studies Course: Political Economy of Development Essay No: 1 Seminar Tutor: Ben Whiston Seminar Group Number: 11 Essay Title: Income Per Capita is One of Many Important Measures of Human Development Submission Date: 14/11/08 Word Count: Income Per Capita is One of Many Important Measures of Human Development Introduction “Wealth is evidently not the good we are seeking; for it is merely useful and for the sake of something else” (Sen, quoting Aristotle, 1999). What Aristotle said is also repeated in different terms by the 1996 Human Development Report: “human development is the end – economic growth the means” (Ravallion, 1997) Income per capita measures the wealth that is ultimately only the means to something else for almost all humans. This fact alone does not diminish its importance when looking at the world and especially developing nations. When considering human welfare, money or income itself is not desirable but it is the products and services that income can buy and the social standing it might create. Higher income will almost certainly lead to higher quality of life since people will have better access to goods like food, shelter, and clothing when their income rises. In the field of development studies an indicator of how countries and regions are progressing is needed, and in the past and present income per capita has been useful at measuring human welfare all over the world. Income per capita cannot consistently predict human development or even indicate how people are living since there are many other variables that play a role when looking at human welfare. Income per capita has shown to have high correlation with human development factors such as access to health care and education and as a consequence higher life expectancy and literacy (Ravallion, 1997, McGillivray, 1991 and Summers & Pritchett, 1996). This paper will discuss how income per capita (PPP values) can be useful in measuring human welfare when used in addition to other measures. The next two sections will show the strengths and limitations of income per capital. I will discuss how income per capita loses most of its usefulness if inequalities are ignored and how there are nations that 1 can have very high human welfare without the usually correlating income by using data from the UNDP’s Human Development Reports. I will argue that income per capita is needed but should never be the sole indicator of human welfare or development. The third section will discuss the Human Development Index as an alternative and how it has approached some of the limitations of income per capita but also how it creates new issues in terms of data and how it is far from all encompassing, by excluding political other freedoms. In conclusion, I will argue that HDI and income per capita should never be the only measures used and the measurement should not be the primary interest but that it is important to take into account how the measures influence policies. Strengths of Income Per Capita Compared to other measures in the development field, income per capita is a fairly straightforward measure to calculate and to use. GDP and GNP data is compiled by various sources and is therefore relatively reliable in terms of calculation and accuracy despite some problems. Income per capita for countries or regions can be portrayed as a single number and is therefore simple to use. It is can also be indicative of rises in health and education, which helps when trying to rank countries and compare them to each other. GDP data is especially easy to obtain compared to the Human Development Index (HDI), which was introduced by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in 1990. The data on GDP does have limitations on what it tells you about human welfare but there are far less problems in obtaining data than with the HDI. The HDI requires data on literacy and life expectancy, which are much harder to acquire. Data on such human development factors usually require some input through household surveys, which are not always available. This leaves data open to errors through misrepresentation or lack of sufficient data. In 2 comparison, income per capita data is either compiled through National accounts or consumption and therefore leaves less room for error and influence from other sources. Despite not being a direct measurement of human welfare, income per capita has been shown to have high correlation with human welfare factors such as health, education and various others. A study by Pritchett and Summers (1996) showed that there is a strong correlation between wealth and health. The study showed that a rise in income per capita has led to a rise in health for various reasons for instance higher productivity of health workers due to higher wages. Pritchett and Summers go even further with their results and claim that higher income causes better health (Pritchett and Summer, 1996, p.844). Their results would indicate that income per capita is not only a good measurement of human welfare but should also be one policy focus when trying to improve health conditions in developing countries in addition to changing health conditions directly through for example more and higher quality hospitals or sending health workers to the developing nations for training of local personnel. Although there is truth in the argument that not all growth is necessarily good for the poor and their welfare, rarely is economic growth leading to worsening of human welfare (Ravallion, 1997). Ravallion states that a 5% rise in average household income leads to a 10% drop in the proportion of people living under the poverty line. This shows that a rise in income per capita usually increases human welfare often through better access to healthcare and education (Ravallion, 1997, p.635). Limitations Measuring growth not development One of the main critiques of using income per capita is that is does not actually measure development. Although a rise in income per capita can indicate that development is taking place, in reality the only thing it can reliably show is economic growth not 3 development. Even if we accept that a significant rise in income per capita is partly due to economic development that does not always translate into higher human welfare such as better healthcare and more opportunities for the poor. Economic development usually includes factors such as rise in productivity, diversification of production, introduction of new technologies and sometimes a rise in exports as products become more competitive; income per capita cannot show these things specifically. If economic growth is not seen because of economic development but because of reasons like exploitation of natural resources, the rise in income is not likely to benefit the population as a whole and will often not be sustainable in the long term. Many of the oil rich nations have seen considerable growth in GDP per capita but this has not translated into the lower income population to benefit from it because large corporations or governments often control natural resources such as oil. Only in countries where the government uses the income from natural resources to increase public spending and provide better social services such as education and healthcare can economic growth lead to increases in human welfare. One example of the problem of using income per capita in oil-rich nations is Equatorial Guinea where GDP has risen sharply since the discovery of oil in 1996 (??? WORLD BANK NUMBERS). The 2007/2008 Human Development Report shows that Equatorial Guinea is ranked 54 places lower in terms of HDI than in GDP per capita (HDR, 2007/08, p.231). This difference is very high compared to other countries and indicates that despite a rise in income per capita it has benefited the living standard of the general population very little. Income per capita cannot capture this problem since it shows an increase even if the majority of inhabitants of the country see little of that increase in their own income. If income per capita can overestimate human welfare in oil-rich nations, it can also do the opposite in other countries, which might have invested more in the human welfare of 4 its citizens. According to the HDR (2007/08, p.231) a country like Myanmar for example ranks 35 places higher when using HDI than GDP per capita. This means that despite very low income, the human welfare seems to be higher compared to countries with similar income per capita. A higher place in HDI ranking than GDP per capita can have various reasons depending on the country. In some cases, the state has invested more in education. Myanmar spent 18.1% of GDP on education in 2002-05 (HDR 2007/08, p.267). Ignoring Inequality The second major limitation of measuring human welfare in income per capita is its lack of information about inequality. There is much discussion about inequality and its effect on growth and development in different regions but in relation to using income per capita as a measurement for human welfare it is more important to see how income per capita in countries with high inequality can skew the perception of human welfare. In statistical terms a few very rich people with high incomes can increase the average income per capita and therefore leave the impression that human welfare is improving, when in a reality the change in income per capita is not reaching the poor and is therefore having very little effect on human welfare (Streeten, 1994, p.235). In countries with high inequality income per capita can be a flawed indicator of human development since the income of the majority of household is most likely significantly below the average due to a few very rich individuals. Botswana is an example where the numbers in the Human Development Report show the danger of using income per capita to assess the situation. The 2007/08 HDR states that Botswana’s place in the world ranking in terms of GDP per capita is 70 places higher than its ranking in the HDI index. This indicates that the country is not using its money in a way that benefits the majority of people in their human development. The HDR’s numbers on inequality show that Botswana has relatively high inequality, which shows in the difference between HDI and income per capita. In the 5 case of Botswana the very high rate of HIV prevalence and the low life expectancy as a consequence probably also play a role in explaining why the HDI is a better indicator in the case of Botswana. These strengths and limitations of income per capita as a measure show that it is certainly one good indicator because it often correlates with other human development factors but as the only measure it can lead to wrong conclusions about the state of human welfare. If looking for initial indication of the economic situation in a county, it can be a good number to look at and should be used for answering some questions in order to better understand how countries are changing their economies. It is useful as long as those who use it for making judgments and policies are aware of its limitations and take other measures into account to counter those problems. It is still a useful measure in many respects and should be considered as one of many factors when looking at development in various countries despite its limitations. The HDI as an Alternative The United Nations Development Program (UNDP) developed the Human Development Index (HDI) as an alternative to using income per capita, since income could only show economic growth and not the human development that accompanies it or the level of human welfare present in a country and as the report states “income is not the sum total of human life” (HDR, 1990) The 1990 Human Development Report introduced the index as a alternative to using income and to re-focus development on human welfare because the 1980s had shown problems such as a lack of social or human development despite GDP growth in some countries and even developed nations were not immune to problems with human welfare (HDR, 1990, p.9-10). The report seems to claim that experts have solely focused on income in the past decades but Srinivasan has said income per capita was never 6 the primary or sole measure for economists or policymakers (Srinivasan, 1994, p.238). The HDI, in addition to taking income into account (PPP values), also uses life expectancy and literacy to determine a country’s HDI. This is certainly useful for policies and for accurately portraying a country’s situation in terms of human welfare. There are cases where the HDI shows conditions very different from income per capita alone, but it is also important to state that for many other cases, countries have shown similar situation when using the HDI or when using income per capita. It is important to look at countries that show great discrepancies between HDI and income ranking to determine if there are fundamental difference in the policies of those countries. After its introduction in 1990 the Human Development Index received widespread attention and critiques from various academics. Hopkins (1991) argues that the HDI is useful but also has its limits and does not show a country’s success in economic growth. Hopkins addresses the widely used example of Sri Lanka. Many experts have used Sri Lanka as an example where human welfare is relatively high considering its low GDP per capita. Hopkins argues that the history of Sri Lanka is not as straightforward as it is sometimes portrayed since the government actually had two very different policy agendas that initially included high social expenditure followed by concentrating on economic growth between 1960-84 (Hopkins, 1991, p. 1471-1472). He also quotes an article by Bhalla and Glewwe who have said that much of Sri Lanka’s success in human development indicators is due to its colonial legacy rather than its policies since independence. Those in favor of using the HDI as an alternative to income per capita should not forget that a study by McGillivray (1991) showed significant correlation between HDI and each of its variables as well as between the variables when including all countries. This indicates that although being useful for combining data on income, literacy and life 7 expectancy the HDI does not necessarily show us anything entirely new or different than the individual components have shown already. Conclusion Measuring human development is a complicated and important issue especially since the kind of measurement and the conclusions drawn from it often have important policy implications, which can directly affect the lives of people in the developing nations. Today the field of development studies uses a variety of measures, some more popular than others. Two of the most important and widely used are income per capita and the Human Development Index developed by the UNDP, other being the Gini coefficient for inequality and some gender indices. Since its creation and publication in 1990 the HDI has received widespread attention from aid agencies, governments and NGOs. Many development workers look favourably to the HDI since it measures those indicators that they aim to change rather than income, which is only the means of human development. When arguing for using the HDI rather than just income per capita, it is important not to ignore the problems that the HDI has. While it is certain that the data used for income is often not completely reliable either, there are fewer problems than with the data for the other HDI components. It is difficult to collect dependable data on each of the HDI’s components, for example adult literacy as well as life expectancy data is often obtained by using neighbouring countries or regions as proxies when real data is unavailable. As Srinivasan (1994) points out, it starts with problems with very basic data on population when a comprehensive populations census has not been done in recent years. According to Chamie as many as 87 out of 117 countries have no reliable data on life expectancy (Srinivasan, 1994, p.16). Often the data is presented as if it was recently collected when in many circumstances approximations or very old data is used (Srinivasan, 1994, p.17). This could 8 mean the HDI is not always a real representation of the situation on the ground and if policy directions are chosen and policy decisions are based on the HDI it is important to make the correct decisions based on the correct data. Otherwise aid agencies could direct their resources towards the wrong priorities. Despite the HDI’s strengths, income per capita should not just be used as a secondary measure or within the HDI. Income in itself might only be the means to an end but in my opinion a country, which is managing to increase human welfare without economic growth, is very likely to do so with money coming into the country through various grants and loans from the foreign aid industry rather than income from its economy. A country that wants to create sustainable increases in human welfare ultimately needs economic growth to finance its increased spending in education and healthcare. Also, I believe that human development as measured by such things as life expectancy and literacy is only truly improving the human conditions if their choices and capabilities increase. Often one of the main factors in increases in capabilities is income. With rising income, people have more choices in terms of the products and services they have access to. Inevitably, income and increases in other human welfare measures interact with each other. Higher income will not only lead to better health and education but people who have are healthier and enjoy better education will also have higher earning potential, leading to an almost circular relationship between income and other measures. Amartya Sen’s Development as Freedom (1999) in the beginning highlights the problem that both income and the HDI only include very limited components of development. Sen’s capabilities approach stresses the importance of other factors and names to many to list. Important is that he includes in his analysis of what development should mean that the capabilities people want is a value judgement, i.e. there are no set capabilities that should be addressed but people’s preferences often guide the capabilities they would 9 like to obtain. Since certainly makes development more complex and it makes a universal approach almost impossible as cultures vary immensely. Sen offers no set list of important capabilities because they vary so much. I agree with Alkire, who in her article on dimensions of human development concludes that any attempt at specifying which capabilities are most valuable should be “collaborative, visible, defensible and revisable” (Alkire, 2002, p.194). 10 Bibliography Alkire, S., 2002, Dimensions of Human Development, World Development, 20(2), pp. 181-205 Hopkins, M., 1991, Human Development Revisited: A New UNDP Report, World Development 19 (10), pp.1469-1473. McGillivray, M., 1991. The human development index: Yet another redundant composite development indicator? World Development, 19(10), 1461-1468. Pritchett, L. & Summers, L.H., 1996. Wealthier is Healthier. The Journal of Human Resources, 31(4), 841-868. Ravallion, M., 1997. Good and bad growth: The human development reports. World Development, 25(5), 631-638. Sen, Amartya, 1999, Development as Freedom, Oxford University Press, Oxford Srinivasan, T.N., 1994. Data base for development analysis Data base for development analysis: An overview. Journal of Development Economics, 44(1), 3-27. Srinivasan, T.N., 1994. Human Development: A New Paradigm or Reinvention of the Wheel? The American Economic Review, 84(2), 238-243. Streeten, P., 1994. Human Development: Means and Ends. The American Economic Review, 84(2), 232-237. United Nations Development Programme, Human Development Report, 1990, Oxford University Press, New York United Nations Development Programme, Human Development Report 2007/08: Fighting Climate Change, Palgrave Macmillan, New York World Bank website for data on equatorial Guinea 11