2011 HSC Paper 2 Module A Advanced: Comparative Study of Texts

advertisement

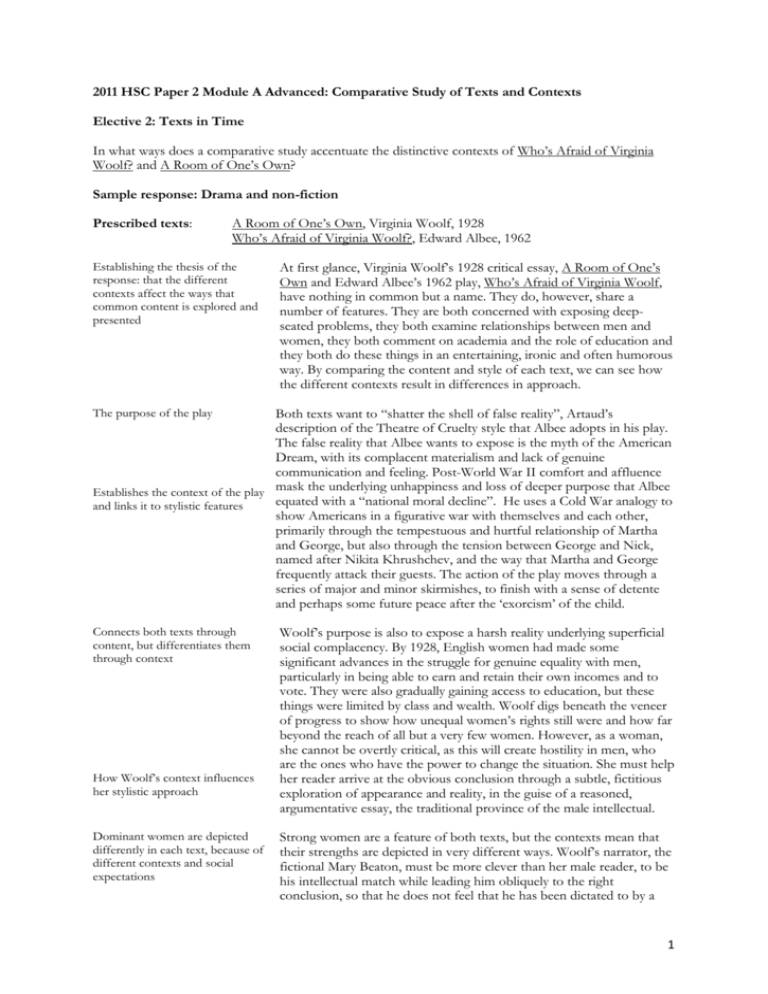

2011 HSC Paper 2 Module A Advanced: Comparative Study of Texts and Contexts Elective 2: Texts in Time In what ways does a comparative study accentuate the distinctive contexts of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? and A Room of One’s Own? Sample response: Drama and non-fiction Prescribed texts: A Room of One’s Own, Virginia Woolf, 1928 Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, Edward Albee, 1962 Establishing the thesis of the response: that the different contexts affect the ways that common content is explored and presented At first glance, Virginia Woolf’s 1928 critical essay, A Room of One’s Own and Edward Albee’s 1962 play, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, have nothing in common but a name. They do, however, share a number of features. They are both concerned with exposing deepseated problems, they both examine relationships between men and women, they both comment on academia and the role of education and they both do these things in an entertaining, ironic and often humorous way. By comparing the content and style of each text, we can see how the different contexts result in differences in approach. The purpose of the play Both texts want to “shatter the shell of false reality”, Artaud’s description of the Theatre of Cruelty style that Albee adopts in his play. The false reality that Albee wants to expose is the myth of the American Dream, with its complacent materialism and lack of genuine communication and feeling. Post-World War II comfort and affluence Establishes the context of the play mask the underlying unhappiness and loss of deeper purpose that Albee equated with a “national moral decline”. He uses a Cold War analogy to and links it to stylistic features show Americans in a figurative war with themselves and each other, primarily through the tempestuous and hurtful relationship of Martha and George, but also through the tension between George and Nick, named after Nikita Khrushchev, and the way that Martha and George frequently attack their guests. The action of the play moves through a series of major and minor skirmishes, to finish with a sense of detente and perhaps some future peace after the ‘exorcism’ of the child. Connects both texts through content, but differentiates them through context How Woolf’s context influences her stylistic approach Dominant women are depicted differently in each text, because of different contexts and social expectations Woolf’s purpose is also to expose a harsh reality underlying superficial social complacency. By 1928, English women had made some significant advances in the struggle for genuine equality with men, particularly in being able to earn and retain their own incomes and to vote. They were also gradually gaining access to education, but these things were limited by class and wealth. Woolf digs beneath the veneer of progress to show how unequal women’s rights still were and how far beyond the reach of all but a very few women. However, as a woman, she cannot be overtly critical, as this will create hostility in men, who are the ones who have the power to change the situation. She must help her reader arrive at the obvious conclusion through a subtle, fictitious exploration of appearance and reality, in the guise of a reasoned, argumentative essay, the traditional province of the male intellectual. Strong women are a feature of both texts, but the contexts mean that their strengths are depicted in very different ways. Woolf’s narrator, the fictional Mary Beaton, must be more clever than her male reader, to be his intellectual match while leading him obliquely to the right conclusion, so that he does not feel that he has been dictated to by a 1 woman. For Woolf, the problem of female dependence is dire, but she fears that her solution of £500 and a room with a lock will be considered so extreme that she must couch the whole text in fictional terms. She presents anecdotes about fictional and real women, in college, in the theatre, in the library and as writers, compares them with men’s experiences in the same situations and feigns surprise that the outcomes should be so different for each gender. Logically, things should not be like this, she suggests. The role of conflict in the play How ideas are presented in A Room of One’s Own Discussion of how Woolf uses irony to emphasise the reality of a situation A different context requires a different approach After World War II, Western women generally enjoyed greater personal freedom than before the war. Martha’s behaviour would not have been possible in 1928 in England. Her open defiance of George and her constant reminders that he owes his teaching position to her father stand in stark contrast to Woolf’s careful reasoning and veiled criticisms. In the war between men and women, Martha is fighting openly and asserting her equal right to engage. This is an important point for Albee, who contends that the conflict, though terrible, means that they are at least communicating with each other and leaves open the possibility for some hope and genuine connection in the end. He prefers her honest open hostility to Honey’s manipulations that trap Nick into marriage. Both texts use humour and irony to emphasise ideas and entertain their audiences. Woolf’s humour is understated and heavily ironic, as befits her educated English readership. Early in the essay, she drolly outlines the differences in status of men and women. Male importance is overemphasised by making proper nouns out of common ones: “He was a Beadle; I was a woman ... only the Fellows and Scholars are allowed here.” She humorously points out her lowly status as a woman by falsely elevating the men. Throughout the essay, she uses this false humility to point out the gap between appearance (she is undeserving because she is a woman) and reality (she is a very clever woman mounting an incisive argument against entrenched discrimination). Woolf’s use of evidence in her essay is often heavily ironic, as well as entertaining. She presents without commentary the inane and offensive statements of important academics and allows the stupidity of their remarks to speak for itself. Thus, she leaves us to assess for ourselves the credibility of statements such as Oscar Browning’s comment that the “best woman was intellectually the inferior of the worst man” or Mr Greg’s assertion that “the essentials of a woman’s being ... are that they are supported by and they minister to men.” We are invited by her silence to evaluate the gap between what has been said and the reality of the situation. Writing for an American theatre audience thirty years later, Albee’s use of humour and irony is much more direct. The dialogue in the play reflects the battle of the sexes and aspects of the American belief in individualism and supremacy of the self, with George and Martha in particular showing scant regard for others and for the conventions of polite conversation. The exchanges between them are often as funny as they are vicious and are designed to shock the audience into recognising some of the problems, especially their dissatisfaction with themselves and each other, and their unhappiness in being caught in the struggle to live up to the “American dream”. The fast-paced dialogue and the way the characters take and switch sides, seemingly on a whim, contribute 2 to the sense of chaos swirling below the surface. George frequently draws attention to the underlying pathos and emptiness of their circumstances. “Good. Better. Best. Bested.” is not just an amusing play on words, but a wry and poignant comment on the futility of conflict and struggle, which are bound to end in defeat. The humour in the dialogue ranges from good-natured teasing, such as when George “joshes” Nick about the abstract painting, to George’s self-mockery as an ABMAPHID, to the savage irony of the characters tearing into each other while continuing to maintain the veneers of hosts and guests. Conclusion confirms that the different contexts result in differences of style The careful style and language of Virginia Woolf’s essay contrast markedly with the raw emotion of the fast-paced dialogue in Albee’s play. Their different styles reflect the differences in their contexts, but both texts nevertheless have much in common, especially in their examination of the relationships between men and women and their underlying inequities. 3

![Special Author: Woolf [DOCX 360.06KB]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006596973_1-e40a8ca5d1b3c6087fa6387124828409-300x300.png)