Nicotine as an Addictive Substance

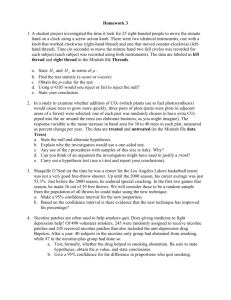

advertisement