Basic Concepts and Vocabulary

advertisement

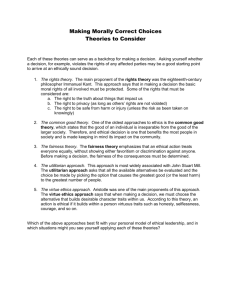

WEEK 1: BASIC CONCEPTS / VOCABULARY Written by Jackie Glover, Ph.D. based on materials of previous course directors and common bioethics literature Introduction: Making ethical decisions, like other decisions in health care, is not a precise art but a learned skill, promising a degree of proficiency and confidence to those willing to take the time and effort to practice. And how ethical decisions are best made has long been an object of intense interest and extensive scholarship. During this course, you will have the opportunity to become familiar with the major ethical principles that frame the moral context of health care and the essential features of ethical decision making, as well as some of the more prominent ethical theories which have been developed to guide that decision making. Acquiring this familiarity will help foster responsible ethical decision making. Differences between the words “moral” and “ethical”: Most people use the words interchangeably. But historically and technically – “moral” refers to personal decisions – often the unreflective result of personal upbringing, culture and societal norms. “Ethical” refers to judgments made about personal moral choices. Ethics is a discipline that intentionally reflects on personal moral choices to critically examine the possible justifications for actions. Profession: A practice or discipline having 4 characteristics: 1) a distinctive body of knowledge and skill 2) that contributes to important social benefits 3) whose members are accorded extensive autonomy in matters pertaining to it and 4) whose members are regarded as having special obligations. From the latin root “profess” meaning to “speak forth” – the moral obligations are the result of this “promise” to put the welfare of patients before self-interest. Principles of Health Care Ethics: a principle is a basic truth, assumption, source that is meant to inform, guide, and shape the behaviors and decisions of those involved 4 major principles in the Bioethics literature and Professional Codes of Ethics: Respect for autonomy – autonomy means “Self-rule” – respecting the choices of people Beneficence – doing good NonMaleficence – not harming Justice – treating people fairly Values: Many people use the terms values and principles interchangeably. We use values in the Process of Ethical Decision Making Template to broaden the scope of ethical “content” to include other actions or traits of character that promote the good, are good, or are otherwise meant to describe actions that are right. In addition to the 4 principles above - examples include: Veracity – telling the truth Fidelity – keeping promises Respect for Life – life having intrinsic value Respect for Persons – not just their decisions – but their privacy, their identity, physical boundaries Confidentiality – not disclosing patient information to others who do not need to know Integrity Family Relationships Compassion Kindness Health Care Relationships Trust Love Ethical Theories: Ethical theories serve as frameworks or perspectives that individual moral agents can bring to bear on the situations confronting them. Just as in the case with science, art, and other areas of applied knowledge, there are competing theories constructed to facilitate the making of ethically responsible decisions. What follows is a very concise overview of predominant theoretical and methodological approaches to ethical decision making. Ethical theories are useful if you don‟t expect them to do more than they can. There is not ONE “true” theory. They all have positive points and drawbacks. They are only organizing structures. No one theory is likely to be able to solve all ethical questions. Arguments are constructed from multiple perspectives according to what can be consistently and coherently applied in many situations and defended against challenges from others. The positions of all of us are improved by constructive dialogue among colleagues with different perspectives. Virtue Ethics: Virtue ethics is characterized by an emphasis on the moral character of the person because it is presumed that morally appropriate decisions occur as a result of being decided by morally sensitive and skilled people. Accordingly, virtue theorists focus principally on the education and development of the agent making the decision. Common virtues are considered to be integrity, fairness, compassion, kindness, openness, and honesty. Deontology or Formalism: Deontological (from the Greek deon for duty) or formalist theories begin with the assumption that what makes an action primarily right or wrong is some intrinsic property not of the moral agent but of the action itself. From a JudeoChristian perspective, for example, it conforms (hence, the term formalism) with one of the term commandments or ten duties. From another point of view, it conforms with the golden rule: “Treat others as you would wish to be treated yourself.” Two of the Four principles are formalistic in nature – respect for autonomy and justice. Consequentialism and Utilitarianism: Consequentialist theories focus on what one seeks to accomplish with an action. Actions which are thought to most likely produce good consequences are good actions; actions which are thought to most likely produce bad consequences are bad actions. Two of the Four principles are consequentialist in nature – beneficence and nonmaleficence. The most prevalent form of consequentialist theory is that theory known as utilitarianism the theory which instructs us to act so as to cause the greatest amount of happiness for the greatest amount of people. Casuistry: The method of casuistry employs case-based reasoning – comparing a new case to a similar paradigm case that has been resolved. The courts proceed in this manner and similarly, we will base our discussions of cases further along in the course on our earlier resolution of cases and to paradigm cases known in the literature. Narrative: One method of understanding the concrete situations of cases is with “narrative” which views health care knowledge as storytelling knowledge. The patient‟s illness is the telling of a story that requires empathy and compassion and that is introduced into the patient-professional relationship through the use of language. We will strive to integrate narrative ethics into our case analysis by beginning our dialogue with a patient story in the form of a poem or short story and by creating our own illness narratives. Differences Between Ethics and Law: The law, through statutes, regulations, and case decisions, also provides guidance about what to do in clinical situations. On many issues the law reflects an ethical consensus in society. Also, court rulings give reasons for their decisions and provided analysis of pertinent issues. But law and ethics have important differences: • Law provides for a minimally acceptable standard of conduct – does not call us to be the best we can be • Law explicitly grants health care professionals discretion in certain settings to exercise professional judgment • Law provides no clear guidance in some circumstances • Law and ethics may conflict • Ethics is the larger construct – we can always ask – is this a good law? Patient-centered Care: Care that respects others as individuals and is organized around their needs. It mandates that practitioners know what it is like to live “a certain kind of life”, and that this requires that they have knowledge of people as individuals. Emphasized the value of patient autonomy. Family-centered Care: Family-centered care is an approach to health care that shapes health care policies, programs, facility design, and day-to-day interactions among patients, families, physicians and other health care professionals. Health care professionals who practice family-centered care recognize the vital role that families play in ensuring the health and well-being of children (and other patients) and family members of all ages. These practitioners acknowledge that emotional, social, and developmental supports are integral components of health care. Family-centered approaches lead to better health outcomes and wiser allocation of resources as well as greater patient and family satisfaction. “Family-Centered Care and the Pediatrician‟s Role.” Committee on Hospital Care. American Academy of Pediatrics. PEDIATRICS. vol. 112. No. 3. September 2003. pp. 691-696. Relationship-Centered Care: Asserts that person-centered care, which privileges individual need, is inadequate. Respect for persons is essential, but personhood is best understood as the standing or status bestowed upon one human being by others in the context of a relationship. From an ethical standpoint, we recognize the importance of autonomy, but assert that we need to subscribe to a relational view of the concept which sees human beings as belonging to a network of social relationships within which they are deeply interconnected and interdependent. Relationship-centered care is a new model for health care delivery that reflects the importance of interactions amongst people as the foundation of any therapeutic or healing activity. Such relationships exist at several levels including those among patients, their families, staff from all disciplines, and the wider community. The interactions among these groups constitute the defining force in health care, as they are the medium for exchanging the information, feelings, and concerns needed for a better understanding of the meaning of illness. “Beyond „personcentred” care: A new vision for gerontological nursing. MR Nolan, S Davies, J Brown, J Keady; and J Nolan. (2004) International Journal of Older People Nursing in association with Journal of Clinical Nursing. 13.3a. 45-53.