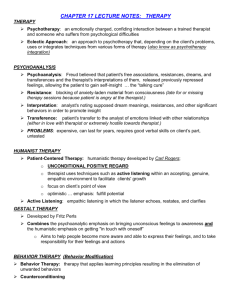

Jorgensen, 2004 - San Francisco Psychotherapy Research Group

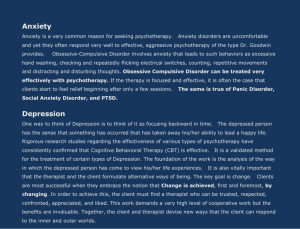

advertisement