People with multiple long term conditions

advertisement

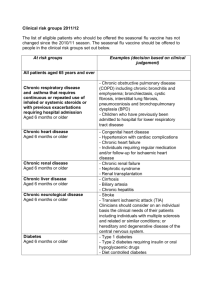

People with multiple long term conditions Key contact/author: Piers Simey, Consultant in Public Health, Buckinghamshire County Council Introduction This section focuses on the needs of people with two or more long term conditions – the standard definition for multimorbidity. A long term condition is one that can be managed but often cannot be cured, and common examples include heart disease, stroke, cancer, diabetes and arthritis. The number of people with long term conditions is increasing, and the majority of people aged over 65 may now have multiple conditionsi. Why is this issue important? People with multiple conditions have poorer health outcomes. Death rates are higher and hospital admissions are more likely, and for longer periodsii iii. Functional ability and quality of life is often reduced, and people with multiple conditions are more likely to be depressed and be on multiple drug treatment regimes which are difficult to manageiv v. The risk of poorer mental health rises with increased numbers of physical conditionsvi. Clinical care for people with long term conditions can be complex. Evidence for managing long term conditions is usually based on research focusing on single conditions which often exclude people with multiple conditionsvii. People with multiple conditions have more problems with the coordination of their care and they experience more medical errorsviii. People living in deprived areas seem to develop and be diagnosed with multiple conditions more than a decade earlier than those in the least deprived areas ix. This will contribute to lower life expectancy and more years spent in poor health. Adverse effects on mental health are also stronger for people living in deprived areasx. Need in the population – current and future Who’s affected/at risk and why? Multiple conditions are more common with age, but significant numbers of people aged under 65 will also be affected Some minority ethnic groups are more affected by certain long term conditions, such as diabetes and heart disease Long term conditions are more common for people living in more deprived areas Around a third of people with a long term condition may also have a mental health problem, typically depression or anxiety. People with cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and chronic musculoskeletal disorders are particularly affected. Some long term conditions are more common for people with learning disabilities. People with serious mental illness often have poor physical health. Size of issue More than 90,000 people in Buckinghamshire in July 2012 had two or more long term conditions, as identified by initial analysis using the Adjusted Clinical Groups (ACG) system used in primary care1. This was 17.6% of those registered with a Buckinghamshire GP2, and the proportion was very similar for both clinical commissioning groups. More than half of people (53.8%) aged over 65 had two or more long term conditions, compared with one in ten people aged under 65. Figure 1 sets out how the numbers of long term conditions that people have increases with age in Buckinghamshire. The blue area in the chart shows the proportion with no long term conditions, while the layers on top show the proportion with increasing numbers of conditions for each age group. Less than one in ten children aged 0-4 years old (8.4%) had at least one condition, rising to a third of adults aged 35 to 44 (33.9%) and almost four fifths of those aged 65+ (77.1%). Having multiple long term conditions is the norm for older people: half of those aged 80+ (50.2%) had three or more long term conditions, around a fifth had either two conditions (19.2%) or one (17.3%), and only 13.4% had no identified long term condition. Figure 1: Number of long term conditions by age group in Buckinghamshire Percentage of people with chronic conditions by age band in Buckinghamshire (July 2012) 100% 90% 80% Percentage 70% 8+ 7 60% 6 50% 5 4 40% 3 2 30% 1 0 20% 10% 0% 00to04 05to11 12to17 18to34 35to44 45to54 55to64 65to69 70to74 75to79 80to84 85+ Age Band Source: ACG system, July 2012 Almost one in five females (19.1%) of any age have two or more long term conditions, compared to 16.0% of males. Figure 2 shows that a higher proportion of 1 The ACG system identifies people with long term conditions on the basis of (a) being on one or more of 19 QOF registers; and/or (b) having a condition from a selected range considered to be life-long. Data is only currently available on the total number of long term conditions affecting each individual 2 524,300 people were registered with a Buckinghamshire GP in April 2012. The ACG system analysed data for 516,500 of these people. people aged 65+ living in the most deprived quintile in Buckinghamshire have two or more long term conditions compared to those living in the least deprived quintile (57.2% vs 52.0%). Further analysis of the numbers and characteristics of those affected will be carried out once data becomes available. This will remain an area of active study. Figure 2: Number of people aged 65+ with 0, one or multiple long term conditions in Buckinghamshire, by deprivation quintile Number of People with 0 to 3+ Chronic Conditions, Aged 65+ by Deprivation Quintile, Bucks 100% 90% 80% Percentage 70% 60% 3+ 50% 2 1 40% 0 30% 20% 10% 0% 1 2 3 4 5 Deprivation Quintile Source: ACG system, July 2012 Around 70% of the total health budget is spent on the care of people with long term conditions. In England it has been estimated that every year between £8 billion and £13 billion of this spend can be attributed to the effects of coexisting mental health problems xi. The future The numbers of people with multiple long term conditions is likely to continue to increase with the ageing of the population in Buckinghamshire. Unhealthy lifestyles will also contribute to this rise, along with the impact of the economic downturn on mental and physical health. Evidence of what works A Cochrane review on interventions for people with multiple long term conditions in the community identified 10 good quality randomised controlled trialsxii. Evidence of what works was limited and there were mixed results. For health service use, only one of the five trials reporting on this issue found significant impact on hospital admissions. Studies considered a range of health related outcomes, with interventions generally more likely to be effective when they targeted: People with specific combinations of common conditions. o Collaborative care management in the USA by nurses for people with poorly controlled diabetes and/or heart disease with coexisting depression significantly improved depression, blood sugar, cholesterol and blood pressure levels at twelve monthsxiii. The intervention group was more likely to meet guideline criteria or achieve clinically significant improvement for these outcomes. Subsequent analysis found that improvements in depression continued a year after the intervention ended, but the improvement in the other outcomes was no longer statistically better than usual carexiv. The intervention cost $1,200 per person. The authors found the intervention to be cost-effective3 on the basis of adjusted outpatient costs. o People with depression and high blood pressure supported by an integrated care manager significantly improved their blood pressure and depressive symptoms over six weeksxv. o Studies targeting specific conditions have had better results than those including people with a wider set of conditions. Problems faced by people with multiple conditions, such as management of multiple medications. Three studies reporting on prescribing and medication use found significant benefits in (a) people taking their medications as prescribed; (b) adjustments to medication by prescribers; or (c) fewer medication related problems following pharmacist medication review. Long term conditions and mental health NICE recommends that cardiac rehabilitation should include psychological support, but complex psychological interventions should not be offered routinelyxvi. NICE also recommends that psychological intervention should be a core part of pulmonary rehabilitation for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseasexvii. NICE guidelines are in place for people with depression and a chronic physical health problem – these are the only NICE guidelines that specifically focus on multiple long term conditions. Collaborative care should be considered for those with moderate to severe depression and a long term condition affecting functional ability, where psychological intervention and/or medication has had no impactxviii. This should include case management supported by a mental health professional. Liaison psychiatry to support people’s mental health needs in hospital – potential for earlier discharge and fewer readmissionsxix. NICE guidelines on multimorbidity in primary care NICE aims to produce guidelines for GPs on managing multimorbidity in 2013/14. 3 Estimated cost per quality adjusted life year under $3,000 (upper estimate) Current services in relation to need People with multiple long term conditions can access the range of care services in place for the population. But there is limited information available on their use of these services and services may focus on managing single diseases. For example only one indicator in the current quality and outcomes framework for primary care specifically relates to people with multiple conditions. In 2011/12, 85.5% of people in Buckinghamshire with diabetes and/or heart disease had been screened within the last fifteen months for depression (range across GP practices: 69.4% - 93.6%). A national pilot project has been established in Wycombe, focusing on access to psychological therapies for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) when they attend rehabilitation. This is an example of a local service set up to focus specifically on the needs of people with multiple long term conditions. Unmet needs and service gaps Care needs to be organised to consider a person’s multiple long term conditions, rather than their individual conditions in isolation. Co-existing mental health problems may be undetected. Many people with multiple long term conditions will benefit from lifestyle changes. Supporting behaviour change needs to be a core consideration in the ongoing care of people with multiple conditions. Care planning needs to be holistic and lead to outcomes being achieved that matter to the individual. Recommendations for consideration by commissioners i Ensure that the care of people with multiple long term conditions is focused on the individual and their range of needs. This includes shared decisionmaking, increased support for self-management, and care planning that assesses physical and psychological needs equally at diagnosis and review. Develop a model for the implementation of routine case finding in primary care to identify mental health problems in people with long term conditions. Ensure access to training on identifying and responding to symptoms of depression among people with long term conditions. Include psychological support within local cardiac and pulmonary rehabilitation programmes. Barnett, K., Mercer, S., Norbury, M., Watt, G., Wyke, S. and Guthrie, B. (2012). Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for healthcare, research, and medical education: a cross sectional study. The Lancet, 380: 37-43. ii Vogeli, C., Shields, A.E., Lee, T.A., Gibson, T.B., Marder, W.D., Weiss, K.B., and Blumenthal, D. (2007). Multiple Chronic Conditions: Prevalence, Health Consequences, and Implications for Quality, Care Management, and Costs. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 22(suppl. 3): 391-5. iii France, E.F., Wyke,S., Gunn, J.M., Mair, F., McLean, G., and Mercer, S.W. (2012). A systematic review of prospective cohort studies of multimorbidity in primary care. British Journal of General Practice, 62: e297-307. iv Fortin, M., Lapointe, L., Hudon, C., Vanasse, A., Ntetu, A.L., and Maltais. (2004). Multimorbidity and quality of life in primary care: a systematic review. Health & Quality of Life Outcomes, 2: 51. v Townsend, A., Hunt, K., and Wyke, S. (2003). Managing multiple morbidity in mid-life: a qualitative study of attitudes to drug use. BMJ, 327: 837-843. vi Barnett, K., Mercer, S., Norbury, M., Watt, G., Wyke, S. and Guthrie, B. (2012). Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for healthcare, research, and medical education: a cross sectional study. The Lancet, 380: 37-43. vii Fortin, M., Dionne, J., Pinho, G., Gignac, J., Almirall, J., and Lapointe, L. (2006). Randomized controlled trials: do they have external validity for patients with multiple comorbidities? Annals of Family Medicine, 4: 104-8. viii Schoen, C. and Osborn, R. (2010) www.commonwealthfund.org/Surveys/2010/Nov/2010International-Survey.aspx (accessed Oct 28 2012). ix Barnett, K., Mercer, S., Norbury, M., Watt, G., Wyke, S. and Guthrie, B. (2012). Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for healthcare, research, and medical education: a cross sectional study. The Lancet, 380: 37-43. x Naylor, C., Parsonage, M., McDaid, D., Knapp, M., Fossey, M., and Galea, A. (2012). Long term conditions and mental health. The cost of co-morbidities. The Kings Fund and Centre for Mental Health. xi Naylor, C., Parsonage, M., McDaid, D., Knapp, M., Fossey, M. and Galea, A. (2012). Long term conditions and mental health. The cost of co-morbidities. The Kings Fund and Centre for Mental Health. xii Smith, S.M., Soubhi, J., Fortin, M., Hudon, C. and O’Dowd, T. (2012). Interventions for improving outcomes in patients with multimorbidity in primary care and community settings. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Issue 4. Article Number: CD006560. xiii Katon, W.J., Lin, E.H., Von Korff, M., Ciechanowski, P., Ludman, E.J., Young, B., Peterson, D., Rutter, C.M., McGregor, M. and McCulloch, D. (2010). Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. New England Journal of Medicine, 363: 2611-20. xiv Katon, W.J., Russon, J., Lin, E.H., Schmittdiel, J., Ciechanowski, P., Ludman, E.J., Peterson, D., Young, B., and Von Korff, M. (2012). Cost-effectiveness of a multicondition collaborative care intervention: a randomised controlled trial. Archives of General Psychiatry, 69(5): 506-14. xv Bogner, H.R. and de Vries, H.F. (2008). Integration of depression and hypertension treatment: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Annals of Family Medicine, 6(4): 295-301. xvi NICE (2007). Secondary prevention in primary and secondary care for patients following a myocardial infarction. xvii NICE (2010). Management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults in primary and secondary care. xviii NICE (2009). Depression in adults with a chronic physical health problem. xix Naylor, C., Parsonage, M., McDaid, D., Knapp, M., Fossey, M., and Galea, A. (2012). Long term conditions and mental health. The cost of co-morbidities. The Kings Fund and Centre for Mental Health.