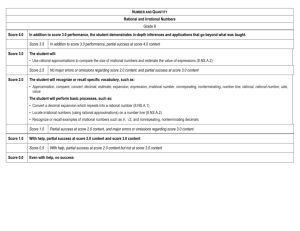

MATH 337 The Real Number System

advertisement

Dr. Neal, WKU

MATH 337

The Real Number System

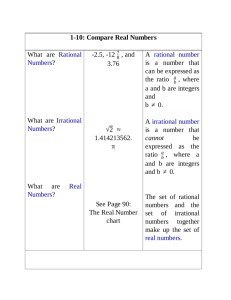

Sets of Numbers

A set S is a well-defined collection of objects, with well-defined meaning that there is a

specific description from which we can tell precisely whether or not an element is in S .

The collection of “large” numbers does not constitute a well-defined set. The set P

of prime numbers is well-defined: P is the collection of integers n that are greater than 1

for which the only positive divisors of n are 1 and n . So we can tell precisely whether

or not an object is in P . For instance 13 ∈ P , but 14 ∉ P because 14 = 7 × 2 .

The set of rational numbers Q is also well-defined. A rational number is an

expression of the form a / b , where a and b are integers with b ≠ 0 . Two rational

numbers a / b and c / d are said to be equal if and only if ad = bc . It is an easy exercise

€

to show that the sum and product

of two rational numbers are also rational numbers.

The set of integers Z is a subset of Q because an integer n can be written as n / 1 .

Proposition 1.1. Let x and y be rational numbers with x < y . There exists another

rational number z such that x < z < y .

Proof. Let z = (x + y) / 2 . Because x , y , and 1/2 are rational, x + y is rational, thus so is

1

1

1

1

× ( x + y) = z . Moreover, x = (x + x ) < (x + y) < (y + y) = y ; thus, x < z < y . QED

2

2

2

2

Existence of Irrational Numbers

The Pythagorean Theorem states: “In a right triangle, the square of the hypotenuse

equals the sum of the squares of the other two sides.” So if we let c be the length of the

2

2

2

hypotenuse of a right triangle with two other sides of length 1, then c = 1 + 1 = 2 .

2

Thus, c is a positive number such that c = 2 ; that is, c = 2 , which exists as a physical

length. But we have already proven using only facts about integers that 2 cannot be

written as a ratio of integers. Thus, c is not a rational number; therefore we call it

irrational. The set of real numbers ℜ is now the union of the rationals and irrationals.

Ordered Sets

Definition 1.1. An order on a set S is a relation on S that satisfies two properties:

(i) (Trichotomy) For all x , y ∈ S , exactly one of the following is true:

xy

or

x=y

or

y x.

(ii) (Transitive) For all x , y , z ∈ S , if x y and y z , then x z .

We write x y to denote that either x y or x = y . Clearly is also transitive.

That is, if x y and y z , then x z .

€

In general, x y is read as “ x precedes y ” thus indicating an ordering to the set.

€ letters. Then a c , c f ,

€

For example,

let S be the set of standard lower-case English

€

and a f . €

Dr. Neal, WKU

We are most concerned with the ordering on the set of real numbers ℜ , and its

various subsets such as the natural numbers ℵ, the integers Z , and the rational

numbers Q . The ordering used for these sets is the relation < (less than). For any two

real numbers x and y , we say x < y if and only if 0 < y − x (i.e., y − x is positive). Then

the relation < satisfies the two properties of an order. With numbers, we read x < y as

“ x is less than y ” and x ≤ y is read as “ x is less than or equal to y .”

Proposition 1.2. Let E = { x1 , . . . , xn } be a finite subset of n distinct elements from an

ordered set. There exists a first (least) element and a last (greatest) element in E .

Proof. If n = 1 , then x1 is both the least and greatest element in E . If n = 2 , then the

result follows from the Trichotomy axiom of order. Now assume the result holds for

some n ≥ 2 , and assume that x1 is the least element and xn is the greatest element in E .

Now consider the set E = { x1 , . . . , xn , xn+1 } with a new distinct element xn+1 . If

xn+1 x1, then xn+1 is the least element and xn is the greatest element in E . If

x1 x n+1 x n , then x1 is the least element and xn is the greatest element in E . If

xn xn+1 , then x1 is the least element and xn+1 is the greatest element in E . With all

cases being exhausted, we see that the result holds for a set of cardinality n + 1 provided

it holds for a set of cardinality n . By induction, the proposition holds for all n ≥ 1. QED

Upper and Lower Bounds

Definition 1.2. Let E be a subset of an ordered set S . (a) We say that E is bounded

above if there exists an element β in S such that x β for all x ∈ E . Such an element β

is called an upper bound of E .

(b) An element β in S is called the least upper bound of E or supremum of E , denoted by

lub E or sup E , if (i) β is an upper bound of E and (ii) if λ is a different upper bound of

E , then β λ .

Note: Suppose β = sup E and λ β . Then λ cannot be an upper bound of E . Thus

there must be an element x ∈ E such that λ x .

1

2

3

n

, 9 + , 9 + , . . .,9 +

, . . . ⊆ ℜ . We claim that

2

3

4

n+1

n

n+1

<9+

= 10 for all integers n ≥ 1; thus, 10 is an upper

sup E = 10 . First, 9 +

n +1

n+1

bound of E . Next, suppose λ is a different upper bound of E but λ < 10 . Obviously

9 < λ or else it would not be an upper bound of E . Then 9 < λ < 10 , which makes

n

0 < λ − 9 < 1 . Because lim

= 1 , we can choose an integer n large enough such

n →∞ n + 1

n

n

that λ − 9 <

< 1 . But then λ < 9 +

< 10 , which contradicts the fact that λ is an

n+1

n+1

upper bound of E . So we must have 10 < λ which makes 10 = sup E .

Example 1.1.

{

Let E = 9 +

}

Dr. Neal, WKU

Proposition 1.3. Let β be an upper bound of a subset E of an ordered set S . If β ∈ E ,

then β = sup E .

Proof. Let λ be a different upper bound of E . Then either λ β or β λ due to the

Trichotomy. But if λ β , then λ would not be an upper bound of E because β ∈ E .

So we must have β λ . Therefore, β is the least upper bound of E .

QED

Definition 1.3. Let E be a subset of an ordered set S . (a) We say that E is bounded

below if there exists an element α in S such that α x for all x ∈ E . Such an element α

is called a lower bound of E .

(b) An element α in S is called the greatest lower bound of E or infimum of E , denoted by

glb E or inf E , if (i) α is a lower bound of E and (ii) if λ is a different lower bound of

E , then λ α .

Note: Suppose α = inf E and α λ . Then λ cannot be a lower bound of E . Thus

there must be an element x ∈ E such that x λ .

Example 1.2. Let E = {1 / n n ∈ℵ} = {1, 1/2, 1/3, 1/4, . . . } ⊆ ℜ . Then sup E = 1 , which

is in E (see Proposition 1.3), but inf E = 0 which is not in E .

Proposition 1.4. Let α be a lower bound of a subset E of an ordered set S . If α ∈ E ,

then α = inf E .

(We leave the proof as an exercise.)

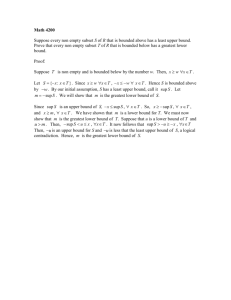

The Least Upper Bound Property

Definition 1.4. An ordered set S is said to have the least upper bound property if the

following condition holds: Whenever E is a non-empty subset of S that is bounded

above, then sup E exists and is an element in S .

Proposition 1.5. The set of integers Z has the least upper bound property.

Proof. Let E be a non-empty subset of the integers Z that is bounded above. Then

there exists an integer N such that n ≤ N for all n ∈ E . Because E is non-empty, there

is an integer n ∈ E with n ≤ N . By Prop. 1.3, if n is an upper bound of E , then

n = sup E which exists as an element in Z . If n is not an upper bound of E , then by

Prop. 1.2. we pick the greatest element in E from among the finite number of integers in

E that are from n to N . By Prop. 1.3, this greatest element in E is sup E and is an

integer because it was chosen from E .

QED

In the proof of Proposition 1.5, we found the least upper bound of the non-empty

subset E and in fact sup E was an element of E . If E were bounded below, then we

also would have inf E ∈ E . We therefore can state:

Dr. Neal, WKU

Proposition 1.6. (The Well-Ordering Principle of Z ). (a) Let E be a non-empty subset

of the integers that is bounded above. Then E has a greatest element within the set E .

(b) Let E be a non-empty subset of the integers that is bounded below. Then E has a

least element within the set E .

The Well-Ordering Principle is essential for the study of limits of sequences, and we

often shall use it implicitly in the manner illustrated in the following example:

∞

Example of the Well-Ordering Principle: Let {an }n =1 be a sequence of real numbers

that increases to infinity. Then we can choose the smallest integer N such that a N ≥ 100 .

Because the sequence is increasing to infinity, we have a1 < a2 < a3 < . . .< an < . . .

and at some point we must have 100 ≤ ak < ak+1 < ak +2 < . . . .

The Well-Ordering Principle is then applied to the set of indices, not to the actual

sequence values. Let E = {k | 100 ≤ ak }, which is the set of indices k for which ak ≥ 100 .

Then E is a non-empty subset of the integers that is bounded below by 1 (the first

index). By the Well-Ordering Principle, E has a least element within E . Thus, there

exists a smallest index N such that a N ≥ 100 .

Example 1.3. The set of rational numbers Q does not have the least upper bound

property. As an example, let E ⊆ Q be defined as follows:

E = {1. 4, 1. 41, 1. 414, 1. 4142, 1.41421, . . .}

a

a

= 1 + 11 + . . .+ kk k ≥ 1, where ai is the ith decimal place value in

10

10

2.

Then E is a non-empty subset of the rational numbers and E is bounded above by 2 .

In fact 2 = sup E , but 2 is not a rational number. Thus, Q does not have the least

upper bound property.

The Greatest Lower Bound Property

Definition 1.5. An ordered set S is said to have the greatest lower bound property if the

following condition holds: Whenever E is a non-empty subset of S that is bounded

below, then inf E exists and is an element in S .

Example 1.4. The set of integers Z has the greatest lower bound property, but the set of

rational numbers Q does not. These results follow from Proposition 1.5, Example 1.3,

and the following theorem:

Dr. Neal, WKU

Theorem 1.1. Let S be an ordered set. Then S has the greatest lower bound property if

and only if S has the least upper bound property.

Partial Proof. Assume S has the least upper bound property and let E be a non-empty

subset of S that is bounded below. Let L be the set of all elements in S that are lower

bounds of E . Then L ≠ ∅ because E is bounded below. Because E is non-empty,

there exists an element x0 in E . By definition of L , x0 is an upper bound of L ; so L is

bounded above. By the least upper bound property of S , α = sup L exists and is an

element of S . We claim that α = inf E .

sup L = α = inf E

L

(All lower bounds of E)

E

S

First, let x ∈ E . By definition of L , x is an upper bound of L ; thus, α x because α

is the least upper bound of L . Thus α is also a lower bound of E . But suppose λ is

another (different) lower bound of E . Then λ ∈ L . But then λ α because α = sup L .

But because λ is different than α , we must have λ α due to the properties of an

order. Thus, α is in fact the greatest lower bound of E and it exists in S . Thus, S has

the greatest lower bound property. (We leave the proof of the converse as an exercise.)

Decimal Expansions: Rational vs. Irrational

A commonly used result is that a rational number has a decimal expansion that

terminates, such as 4.0 (an integer) or 2.375 (a regular number), or has a decimal

expansion that recurs such as 5.342 . This property characterizes rational numbers and

therefore provides another distinction between rational and irrational numbers.

Theorem 1.2. A real number is rational if and only if it has a decimal expansion that

either terminates or recurs.

Proof. Assume first that we have a real number x with a decimal expansion that either

terminates or recurs. If it terminates, then x has the form x = ± (n. a1a2 . . .ak ) , where

n,a1 , . . ., ak are all non-negative integers, and 0 ≤ ai ≤ 9 for 1 ≤ i ≤ k .

Thus,

a

a

x = ± n + 11 + . . . + kk is the sum of rational numbers which is rational. (If all ai are

10

10

x

=

±

n

0, then

is an integer and thus is a rational number.) If the decimal expansion is

recurring, then x has the form

Dr. Neal, WKU

x = ± n. a1 . . .a j a j+1 . . .a j +k a j +1 . . . a j+ k a j+1 . . . a j +k . . .

aj

a j +k

a j +k

a

1 a j+1

1 a j +1

= ± n + 11 + . . .+ j + j

+ . . . + k + j k +1 + . . .+ 2k + . . .

10

10

10 10

10 10 10

10

a

a

1

a j +k 1

a

1

1

1

1

= ± n + 11 + . . + jj + j +1

+

+

+.

.

+

.

.

+

+

+

+.

.

10

10

10 j 10 10 k+1 102 k+1

10 j 10 k 10 2k 103k

i

i

aj

a j +1 ∞ 1

a j +k ∞ 1

a1

= ± n + 1 + . . .+ j + j +1 ∑ k + . . .+ j +k ∑ k

10

10

10

10

i = 0 10

i = 0 10

a j +k ∞ 1 i

a j a j+1

a1

= ± n + 1 + . . .+ j + j +1 + . . . + j+ k ∑ k

10

i = 0 10

10

10

10

aj

a j +k

a

1 a j+1

10 k

= ± n + 11 + . . .+ j + j 1 + . . . +

×

, which is rational .

10

10

10 10

10 k 10 k − 1

Conversely, let x = c / d be a rational number. We must obtain its decimal

expansion. By dividing d into c , we may assume that x is of the form x = ± (n + a / b) ,

where n,a,b are non-negative integers with b ≠ 0 and 0 ≤ a < b . If a = 0 , then x = ± n

is a terminating decimal expansion.

If a ≠ 0 , then let r0 = a and divide b into 10r0 to obtain

10r0 = a1 b + r1 where 0 ≤ r1 < b and 0 ≤ a1 ≤ 9 because 0 ≤ r0 < b .

Then divide b into 10r1 to obtain

10r1 = a2 b + r2 where 0 ≤ r2 < b and 0 ≤ a2 ≤ 9 because 0 ≤ r1 < b .

Continue dividing b into 10r j to obtain

10r j = a j +1 b + r j +1 where 0 ≤ r j+1 < b and 0 ≤ a j +1 ≤ 9 because 0 ≤ r j < b .

Because all remainders ri must be from 0 to b − 1 , there can be at most b distinct

remainders. At some point, we will have 10rk = ak+1 b + rk +1 , where rk +1 = ri for some

previous remainder ri . Because the next step of dividing 10ri by b yields the same

quotient ai+1 and remainder as before, the pattern recurs for the successive divisions.

We now claim that x = ± (n. a1a2 ... ai ai+1. .ak +1 ai+1 . . ak+1 ai+1 . . ak+1 . . . ) To see this

result, we first use 10a = 10r0 = a1 b + r1 . Dividing by 10b gives

a a1 1 r1

=

+ .

b 10 10 b

r

a

1 r

But then 10r1 = a2 b + r2 , which gives 1 = 2 + 2 ; hence,

b 10 10 b

Dr. Neal, WKU

a a1 1 a2 1 r2 a1 a2

1 r

=

+

+ =

+ 2 + 2 2 .

b 10 10 10 10 b

10 10

b

10

Continuing, we obtain

a a1

a

a

a

a +1

1 r

=

+ 22 + . . .+ ii + ii+1

+. . . + kk+1

+ k +1 k +1 ,

+1

b 10 10

b

10

10

10

10

where rk +1 = ri . But then we have

a a1

a

a

a

a +1

a

1 r

=

+ 22 + . . .+ ii + ii+1

+. . . + kk+1

+ ik+1

+ k +2 i+1

+1

+2

b

b 10 10

10 10

10

10

10

a

a

a

a

a +1

a

a 2

1 r

= 1 + 22 + . . .+ ii + ii+1

+. . . + kk+1

+ ik+1

+ i+

+ k +3 i +3

+1

+2

k

+3

b

10 10

10 10

10

10

10

10

a

a

a

a

a +1

a

a 2

ak +1

= 1 + 22 + . . .+ ii + ii+1

+. . . + kk+1

+ ik+1

+ i+

+. . . + 2(k+1)−i

+1

+2

k

+3

10 10

10 10

10

10

10

10

r

1

+ 2(k+1)−i k+1

b

10

By recursion, we obtain a recurring decimal expansion of x that terminates if b ever

divides evenly into a remainder.

QED

Example 1.5 (a) Find the rational form of 5.86342342342 . . .

expansion of 3/8. (c) Find the decimal expansion of 3/14.

(b) Find the decimal

Solution. (a) By Theorem 1.2, we have

8

6

1

103

+

+

× 0.342 × 3

10 100 100

10 − 1

8

6

1

342

=5+

+

+

×

10 100 100 999

8

6

342

16271

=5+

+

+

=

.

10 100 99900

2775

5.86342 = 5 +

(b) For a / b = 3 / 8 , we first divide 8 into 10 × 3 to obtain the next remainder r1 , then

continue dividing 8 into 10ri until we obtain a 0 remainder or a repeated remainder.

The decimal terms of 3/8 come from the successive quotients:

30 = 3 × 8 + 6

60 = 7 × 8 + 4

40 = 5 × 8 + 0

0 = 0 × 8+ 0

Thus, 3/8 = 0.375.

Dr. Neal, WKU

(c) For a / b = 3 / 14 , we first divide 14 into 10 × 3 to obtain the next remainder r1 , then

continue dividing 14 into 10ri until we obtain a 0 remainder or a repeated remainder.

The decimal terms of 3/14 come from the successive quotients:

30 = 2 × 14 + 2

20 = 1 × 14 + 6

60 = 4 × 14 + 4

40 = 2 × 14 + 12

120 = 8 × 14 + 8

80 = 5 × 14 + 10

100 = 7 × 14 + 2 ← repeated remainder

20 = 1 × 14 + 6

↑ repeated quotient

Thus, 3/14 = 0.2142857142857...

Note: The decimal expansion of a rational number is not unique. An expansion that

terminates also can be written as an expansion that ends in a string of all 9's.

Specifically, the decimal x = n.a1a2 ... ak , where 1 ≤ ak ≤ 9 , can be re-written as

x = n.a1a2 ... (ak − 1) 999999 . . . . This result follows from the geometric series

1 i

(1 / 10)k+1

(1 / 10)k+1 1 k

9 ∑ =9×

= 9×

= .

10

1

−

1

/

10

9

/

10

10

i = k +1

∞

For example, with k = 3 we have 0.000 9999 . . .= 0.001 . As another example, we

have 2.4837 = 2.48369999 .

By convention, we always shall assume that a

rational number never ends in a string of all 9's.

An immediate consequence to Theorem 1.2 is the following result:

Corollary 1.1. A number is irrational if and only if it has a decimal expansion that

neither terminates nor recurs.

We have already seen that 2 is irrational. An example of another irrational number is

x = 0.123456789112233445566778899111222333 . . .

Dr. Neal, WKU

Another Construction of the Reals

Theorem 1.2 and Corollary 1.1 give a method of constructing the real numbers based on

the natural numbers. A brief outline of the steps follows:

I. Let 0 denote no length and let 1 denote a fixed unit of length.

II. By extending the initial length of 1 by incremental successive lengths of 1, we obtain

the natural numbers ℵ = {1, 2, 3, . . .}. Including 0 gives us the whole numbers W .

III. By considering all quotients a / b of natural numbers, we obtain the positive

rational numbers Q+ . Also allowing a = 0 gives us the non-negative rational numbers.

∞ a

IV. Every element in Q+ can be written uniquely in the form n + ∑ ii , where n ∈ W ,

i = 1 10

0 ≤ ai ≤ 9 for all i , the sequence {ai } either terminates by ending in all 0's or is

recurring, and the sequence {ai } does not end in a string of all 9's.

+

V. Let the non-negative irrational numbers I be defined by all values of the form

∞ a

n + ∑ ii , where n ∈ W , 0 ≤ ai ≤ 9 for all i , and the sequence {ai } neither terminates

i = 1 10

nor recurs. (In particular, irrational numbers also cannot end in a string of all 9's.)

VI. Let the positive real numbers be defined by R + = Q+ ∪ I + .

∞ a

i

VII. Negative numbers can be written in the form − n ± ∑

i

i =1 10

.

A real number is therefore either rational or irrational. By comparing the decimal

expansions of any two real numbers x and y , we can see that either x < y , x = y , or

y < x . Thus, the Reals are ordered. The next results prove that both the rational

numbers and the irrational numbers are dense within the Reals.

Theorem 1.3. Let x and y be any two real numbers with 0 ≤ x < y .

(a) There exists a rational number z such that x < z < y .

(b) There exists an irrational number w such that x < w < y .

Proof. Let x = m. a1a2 a3 . . . and y = n. b1b2 b3 . . . be the decimal forms of x and y where

0 ≤ m ≤ n . Suppose first that m < n . Because x cannot end in a string of all 9's, let ai be

the first decimal place value such that ai < 9 . Then change ai to ai + 1 and let

z = m. a1a2 a3 . . .(ai + 1) , which is rational, and let w = m. a1a2 a3 . . .(ai + 1)c1c2 c3 . . . ,

where the sequence {ci } neither terminates nor recurs, so that w is irrational. We then

have x < z < y and x < w < y .

Dr. Neal, WKU

Next assume that m = n . Because x < y , we must have a1 ≤ b1 . We now choose the

smallest index i such that ai < bi . Then we must have a j = b j for 1 ≤ j < i or else x

would be larger than y . Now because x cannot end in a string of all 9's, choose the

least k ≥ i such that ak < 9 . Now let z = m. a1a2 a3 . . .ai . . .(ak + 1) . Then z is rational

and x < z < y . Finally, let w = m. a1a2 a3 . . .ai . . . (ak + 1)c1c2 c3 . . . where the sequence

{ci } neither terminates nor recurs, so that w is irrational. Then x < w < y .

QED

Corollary 1.2. Let x and y be any two real numbers with x < y .

(a) There exists a rational number z such that x < z < y .

(b) There exists an irrational number w such that x < w < y .

Proof. If 0 ≤ x < y , then the result is proved in Theorem 1.3. If x < 0 < y , then by

Theorem 1.3, we can find such z and w such that x < 0 < z < y and x < 0 < w < y .

If x < y ≤ 0 , then 0 ≤ − y < − x . So we can apply Theorem 1.3 to find a rational z and

an irrational w such that − y < z < − x and − y < w < − x . But then − z is rational and − w

is irrational with x < − z < y and x < − w < y .

QED

Example 1.6. Apply Theorem 1.3 to x = 8.9942 . . . and y = 9.01 assuming x is rational

and assuming x is irrational.

Solution. Let z = 8.995 , which is rational. Then x < z < y regardless of whether x is

rational or irrational.

If x is irrational, then let w = x + 0.001 , which is irrational. Then x < w < y .

However if x is rational, then let w = 8.995 + ( 2 − 1) / 1000 = 8.9954142 . . . , which is

irrational. (This expression simply appends the decimal digits of 2 to the end of

8.995.) Then x < w < y .

We continue with two of the most important property of real numbers:

Theorem 1.4. The set of real numbers has the greatest lower bound property.

Proof. Let E a non-empty subset of ℜ that is bounded below. Let r ∈ ℜ be a lower

bound of E and let F be the set of all integers k such that k ≤ r . Then r is an upper

bound of F ; thus, by Prop. 1.6, we can choose a greatest element n in F . Then n ≤ r ,

so n is also a lower bound of E . By Prop. 1.4, if n ∈ E , then n = inf E . Otherwise, we

continue: Choose the greatest integer a1 from 0 to 9 such that n + a1 / 10 is a lower

bound of E . If n + a1 / 10 ∈ E , then n + a1 / 10 = inf E . Otherwise, choose the greatest

integer a2 from 0 to 9 such that n + a1 / 10 + a2 / 102 is a lower bound of E .

Dr. Neal, WKU

Continuing, we thereby obtain a real number α = n + ∑i∞=1 ai / 10i with α ≤ n + 1.

We claim α = inf E . So let x ∈ E . By construction, n + ∑ik=1 ai / 10i ≤ x for all k ≥ 1 . In

particular, n ≤ x .

If n + 1 ≤ x , then α ≤ n + 1 ≤ x .

But suppose x < n + 1 with

∞

i

x = n + ∑i =1 bi / 10 where the string {bi} does not end in all 9's. If we had x < α , then

we must have bk < ak for some k and we can choose the smallest integer k for which

this occurs. But then we would have x < n + ∑ki =1 ai / 10i , which is a contradiction.

Thus, α ≤ x ; that is, α is a lower bound of E .

Next, suppose λ is a different lower bound of E . We must show that λ < α . So

i

write λ = m + ∑∞

i =1 ci / 10 Then m ≤ λ , so m is also a lower bound of E . By the choice

of n above, we must have m ≤ n. If m < n , then λ < α . So suppose m = n . Now if

ak < c k for some k and we choose the smallest k where this occurs, then we would

k

have n + ∑ ci / 10i ≤ λ ≤ x for all x ∈ E . But then this ck contradicts the choice of ak .

i=1

So we must have ck ≤ ak for all k . That is, λ ≤ α . But because λ is different that α , we

must have λ < α . That is, α = inf E .

QED

From Theorems 1.1 and 1.4, we obtain:

Corollary 1.2. The set of real numbers has the least upper bound property. That is, any

non-empty subset of ℜ that is bounded above has a least upper bound in ℜ .

An important consequence of the glb and lub properties of the real line is the fact

that the intersection of a nested decreasing sequence of closed intervals is non-empty:

[a1 , b1 ] ⊇ [a2 , b2 ] ⊇ [a3 , b3 ] ⊇ . . . ⊇ [sup{ai }, inf{bi}]

a1 ≤ a2 ≤ a3 ≤ . . . ≤ ai ≤ . . . ≤ sup{ai} ≤ inf{bi } ≤ . . . ≤ bi ≤. . . ≤ b3 ≤ b2 ≤ b1

Theorem 1.5. (Nested Interval Property) Let [ai , bi ] be a nested decreasing sequence of

∞

∞

i =1

i =1

closed intervals. Then [sup{ai }, inf{bi}] ⊆ [ai , bi ] . In particular, [ai , bi ] ≠ ∅ .

Proof. Because the intervals are nested decreasing, we have ai ≤ ai+1 ≤ bi+1 ≤ bi for i ≥ 1.

So the set of points {ai } is bounded above by each bi and the set of points {bi} is

bounded below by each ai ; hence a = sup{ai } and b = inf{bi} exist by the least upper

bound and greatest lower bound properties of ℜ .

Because each bi is an upper bound of {ai } and a is the least upper bound of {ai },

we have a ≤ bi for all i ≥ 1. But then a becomes a lower bound of the {bi} ; so a ≤ b

because b is the greatest lower bound of the {bi} . For all i ≥ 1, we then have

∞

∞

i =1

i =1

ai ≤ a ≤ b ≤ bi ; thus, [a, b] ⊆ [ai , bi ] . In particular, [ai , bi ] contains a and b . QED

Dr. Neal, WKU

Exercises

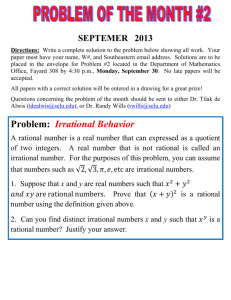

1. Prove: If c is rational, c ≠ 0 , and x is irrational, then c x and c + x are irrational.

2. Prove that 12 is irrational.

3. Let E be a non-empty subset of an ordered set. Suppose α is a lower bound of E

and β is an upper bound of E . Prove that α β .

4. Let E be a non-empty subset of an ordered set S that has the least upper bound

property. Suppose E is bounded above and below. Prove that inf E sup E .

5. Let S be a non-empty subset of the real numbers that is bounded below. Define − S

by − S = {− x x ∈ S }. Prove: (i) − S is bounded above. (ii) lub(−S) = −glb S .

6. Prove: Let α be a lower bound of a subset E of an ordered set S . If α ∈ E , then

€

α = inf E .

7. Let S be an ordered set with the greatest lower bound property. Prove that S has the

least upper bound property.

8. Find a rational number and an irrational number between x = 8.9949926 and

y = 8.995 .

9. Let a,b ∈ℜ with a < b ,

(i) For the open interval E = (a, b) , prove that inf E = a and sup E = b .

(ii) For the closed interval F = [a, b], prove that inf F = a and sup F = b .

€

€