The Domain of Rational Expressions

advertisement

Rational Expressions

Remember rational numbers? The rational numbers are all real numbers that can be written as a fraction. Similarly, rational expressions are

expressions that can be written as a fraction. For example,

2

,

3

1

,

x+1

and

x2 + 2x + 1

2x + 2

are rational expressions because they are written as a fraction. Typically, we

talk about rational expressions where the numerator and denominator are

both polynomials.

The Domain of Rational Expressions

Have you ever typed “1 / 0” into your calculator? If you have, it says: “ERROR: ILLEGAL DIVISION BY ZERO.” This is because zero can NOT be

in the denominator of ANY expression. The same thing goes for rational expressions that are quotients of polynomials. Therefore, we have a restriction

on the values we can plug in to any rational expression. Specifically, we can

not have a denominator of zero. This means that the expression is undefined

for whatever x values make the denominator equal to zero. In general, the

domain of an algebraic expression is the set of all real numbers for which

the expression is defined. Since rational expressions are undefined when the

denominator is zero, the domain of a rational expression is the set of all real

numbers such that the denominator is not zero.

For example, what is the domain of

x2 − 4

x2 + 4x + 2

From the definition, it is the set of all real so that x2 + 4x + 2 6= 0. Since this

is hardly ever zero, it will be easier to find when it is equal to zero. Then

the domain is all real numbers except those that make the denominator zero.

Thankfully, we can factor the denominator into

x2 + 5x + 6 = (x + 2)(x + 3) = 0

when

x = −3 or x = −2

Therefore, our domain is the set of all real numbers x such that x does

not equal -2 and x does not equal -3. We can write this is set notation as:

1

{x ∈ R|x 6= −3 and x 6= −2}. This is also sometimes written as {x|x is a real

number and x 6= −3 and x 6= −2}. Sometimes, “:” is used as the separator

instead of “|”, it just depends on the book.

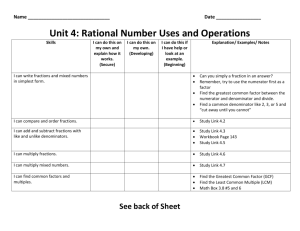

Manipulating Rational Expressions

Rational expressions show up in many places in algebra, and it is very important to be comfortable working with them. This means:

• simplify rational expressions to make them easier to work with

• add and subtract rational expressions to look for more simplifications

• multiply and divide rational expressions to combine them for further

simplification

All of these skills are necessary to effectively work with rational exressions.

These expressions can become cumbersome very quickly, and it is essential

to have these skills mastered in order to use them as tools to solve other

problems rather than the first step you didn’t see.

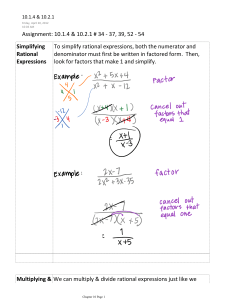

Simplifying Rational Expressions

Simplifying rational expressions is all about multiplying by 1. The trick is

to find all of these factors of 1 hidden in the problem. First, recall that for

any real number x 6= 0,

x

=1

x

Therefor, whenever we have a factor in the numerator and denominator that

are the same, we can “cancel” the terms. Consider the example used in the

previous section:

x2 − 4

x2 − 4

(x + 2)(x − 2)

x+2 x−2

x−2

x−2

=

=

=

·

= 1·

=

2

x + 4x + 2

(x + 2)(x + 3)

(x + 2)(x + 3)

x+2 x+3

x+3

x+3

Therefore, we have simplified the domain example:

x2 − 4

x−2

=

x2 + 4x + 2

x+3

2

However, the domain of the simplified expression is {x ∈ R|x 6= −3}, which

is NOT the same as the original domain. This is because the two expressions

are not quite equal. They are equal when BOTH are defined. In other words,

they are equal for all x that are in BOTH domains. These expressions are

called equivalent expressions because they are not truly equal, but they

have the same value for all numbers that are in both domains. These two

x−2

domains are different because the domain of x+3

has -2 in its domain, but the

x2 −4

original expression x2 +4x+2 is not defined for this value because the denominator is zero. This leads to an important point. WHEN YOU SIMPLIFY

AN EXPRESSION, YOU DO NOT CHANGE THE DOMAIN!

Arithmetic Operations Involving Rational Expressions

Rational expressions work just like fractions. You add, subtract, multiply

and divide rational expressions the same way you do fractions.

Multiplication is the easiest operation to carry out on fractions. Simply multipily the numerators to get the new numerator, and multiply the

denominators to get the new denominator. For example:

a c

a·c

· =

b d

b·d

In other words, just multiply straight across to get the answer.

Division is almost as simple as multiplication. In fact, you can turn a

division problem with fractions into a multiplication problem. For a longwinded example, consider:

a c

÷ =

b d

=

a·d

b·c

c·d

c·d

a

b

c

d

=

=

a·d

b·c

1

a

b

c

d

·1=

=

a

b

c

d

·

d

c

d

c

=

a·d

b·c

c·d

d·c

a·d

a d

= ·

b·c

b c

a d

a c

÷ = ·

b d

b c

Ok. That was long and laborious. However, we did not break any of the rules

(provided c 6= 0 and d 6= 0, which would make no sense from the beginning

since the initial problem would have division by zero). The bottom line of

that was to show that we can change a division problem into a multiplication

Therefore

3

problem if we use the reciprocal of the term we are dividing by. In other

words, we just “flip the second and multiply.” For a concrete example with

numbers:

1 5

1·5

5

1 2

÷ = · =

=

3 5

3 2

3·2

6

Of course, we would have to reduce this answer if we could, such as in this

example:

2 4

2 7

2·7

14

2·7

2 7

7

÷ = · =

=

=

= · =

3 7

3 4

3·4

12

2·6

2 6

6

We had to reduce this final answer. It is always good to reduce the final

answer if it is possible.

When you want to add or subtract fractions, you need a common denominator. Of course, it makes life easier if you have the least common

denominator of the expression. However, it is not completely necessary to

find the least commond denominator because you can simplify the expression after you perform the operation. It just may be easier to find the least

common denominator at the beginning so you do not have to worry about

simplifying a complicated expression at the end. For example, say we want

to subtract

1 1

−

4 2

We can see that 4 = 2 · 2, so the least common denominator is 4. Then, we

can solve this:

1 1

1 1

1 1 2

1 2

1

− = − ·1= − · = − =−

4 2

4 2

4 2 2

4 4

4

However, we can add general fractions by forcing the denominators to be

common denominators (which may not be the least common denominator).

This is accomplished by multiplying both terms by 1, except we use a specific

way of writing it. We multiply by 1 as xx where x is the denominator of the

other term:

a c

a

c

a d c b

a·d c·b

a·d c·b

a·d+c·b

+ = ·1+ ·1 = · + · =

+

=

+

=

b d

b

d

b d d b

b·d d·b

b·d b·d

b·d

Sometimes this is called “cross multiplying” because we end up with a numerator of the sum of the terms you would get if you made an X between the

fractions and multiplied the terms opposite each other, and the denominator

is the product of the denominators:

a c

ad + bc

X =

b d

bd

4

What we have here is ad from the \ part of the X, and bc from the / part of

the X. Then, the denominator is the product of the old denominators.

We can easily write any subtraction as an addition problem as:

a

c

a −1 c

a −1 · c

a −c

a c

− = + (−1) = +

· = +

= +

b d

b

d

b

1 d

b

1·d

b

d

So, we now know how to add, subtract, multiply and divide fractions.

Thankfully, rational expressions are nothing other than fractions. The

bad thing is that we do not know the numbers that are the numerator and

denominator because they depend on some variable. However, all we have to

worry about is not dividing by zero. For this reason, we have to make sure

that we take note of the x values that will make the denominator of any of

the terms in the original expression zero. Then, we say the expression is not

defined for these x values by specifying our domain, as stated earlier. If you

know how to add, subtract, multiply and divide fractions, you know how to

add, subtract, multiply and divide rational expressions.

However, the problem comes in when we are faced with the task of reducing the fraction. It is a good idea to factor the original expressions

completely before trying to perform any operations. When multiplying (and

dividing, since it is essentially a multiplication), it is a good idea not to multiply the terms out. After an addition or subtraction, it is a good idea to try

to factor again. Doing these makes it easier to:

• find the domain of the expression

• find the least common denominator of an expression

• simplify the expression by cancelling terms

Now that we have an idea of how to attack these problems, let’s do some

examples.

x2 − 4

x2 − 4x + 3

÷

x2 + 2x + 4

x4 − 9x2

First, we factor all of the expressions:

(x − 2)(x + 2)

(x − 3)(x − 1)

÷ 2

2

(x + 2)

x (x − 3)(x + 3)

Now, we need to figure out the domain. From the first term, we know we

can not have x + 2 = 0 i.e. x 6= −2. In the second term, we can not have

5

a denominator of zero, so x 6= 0, x 6= 3 and x 6= −3. Finally, since we are

dividing by the entire second term, it can not equal zero. Therefore, the

numerator of the second term can not be zero either. This happens when

x = 3 or x = 1. Putting it all together, our domain is {x ∈ R such that

x 6= −3 and x 6= −2 and x 6= 0 and x 6= 1 and x 6= 3}. Next, we simplify:

(x − 1) x − 3

(x − 2)(x + 2)

(x − 3)(x − 1)

x−2x+2

÷ 2

=

÷

=

(x + 2)2

x (x − 3)(x + 3)

x+2x+2

x2 (x + 3) x − 3

(x − 1)

x−2

(x − 1)

x−2

·1÷

·1 =

÷ 2

2

x+2

x (x + 3)

x + 2 x (x + 3)

We still have not done anything except find the domain and simplify. Now,

we can “flip the second and multiply.”

x − 2 (x − 1)

x − 2 x2 (x + 3)

(x − 2)x2 (x + 3)

x2 (x − 2)(x + 3)

÷ 2

=

·

=

=

x + 2 x (x + 3)

x+2 x−1

(x + 2)(x − 1)

(x + 2)(x − 1)

At this point, we try to simplify. However, there are no common factors in

the numerator and denominator, so we can not do anything else. We can

either leave this as it is, or multiply it out. We will leave this as it is.

Now, consider a more complicated example.

1

+ y12

x

x

− xy

y

This problem incorporates all of the operations of fractions. However, there

is not much we can do to this. Order of operations tells us to do parenthases

then exponents. Niether of those appear in this equation. Then, we are supposed to multiply and divide next. However, we do not know the reciprocal

of the entire denominator. Therefore, we have to simplify it. We can work

with the numerator and the denominator and try to make each of them one

fraction by performing the addition or subtraction:

1

+ y12

x

x

− xy

y

=

1 y2

·

x y2

x x

·

y x

+

−

1

·x

y2 x

y y

·

x y

=

y2

xy 2

x2

xy

+

−

x

xy 2

y2

xy

=

x+y 2

xy 2

2

x −y 2

xy

Since we have not cancelled any terms, we have not changed the domain

yet. So, we will get the domain from this expression. We know that xy 2

can not equal zero, and xy can not equal zero. Finally, since the entire big

6

denominator can not be zero, x2 − y 2 can not equal zero. We know from the

first two conditions that x 6= 0 and y 6= 0. Now, lets find when x2 − y 2 = 0.

This happens when x2 = y 2 , or when x = ±y (because (−a)2 = a2 for all

real numbers a). Therefore, our domain is {x ∈ R such that x 6= 0, y 6= 0

and x 6= ±y}.

The expression can now be rewritten as

x+y 2

xy 2

2

x −y 2

xy

=

x + y2

xy

x + y 2 x2 − y 2

÷

=

·

xy 2

xy

xy 2

x2 − y 2

Now, we can factor and then multiply:

x + y2

xy

x + y2

xy

(xy)(x + y 2 )

·

=

·

=

xy 2

x2 − y 2

xy 2

(x + y)(x − y)

xy 2 (x + y)(x − y)

Now, we can simplify this by canceling xy:

(xy)(x + y 2 )

(x + y 2 )

xy

=

·

=

2

xy (x + y)(x − y)

y(x + y)(x − y) xy

(x + y 2 )

(x + y 2 )

·1=

y(x + y)(x − y)

y(x + y)(x − y)

At this point, there is no further simplification possible. We can not factor

the numerator any more, so we will not be able to cancel with any of the

terms in the denominator.

7